Guest Blogger Max Pivonka

In this recent Saturday Night Live sketch, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler satirically imitate Sarah Palin and Katie Couric, respectively. Satire is defined by Lisa Colletta, the Dean of Academic Affairs at the American University of Rome, as “a form that holds up human vices and follies to ridicule and scorn” (Colletta). In this sketch, Saturday Night Live holds up some of the vices they believe Sarah Palin possesses and severely ridicules them utilizing satire. As the Huffington Post notes, “Fey’s portrayal of Palin didn’t merely entertain. It shaped public perceptions” (Cooper).

Using satire has the power to shape how individuals view prominent issues within American politics, and, along with The Colbert Report and The Daily Show, Saturday Night Live has been one of the most effective television programs that uses satire to sway American public opinion on political issues. Saturday Night Live has been on the air since 1975, amassing 41 seasons and offering satirical discourse on presidents from Jimmy Carter to Barack Obama as well as every President and candidate in between the two. Although The Daily Show and The Colbert Report both use satire effectively, one thing sets Saturday Night Live apart from its competitors: the use of improvisation.

Saturday Night Live successfully combines prepared rhetoric with improvisation to create side-splitting laughs that also deliver a bigger message. Although many of the sketches produced by the show are created beforehand, a character or two within the sketch usually is given the ability to improvise while performing to increase the effectiveness of the sketch. Amy Seham, an artistic director in Michigan and Connecticut, notes that, on the topic of improvisation, “It remains the case, however, that successful improv-comedy often depends on some improvisers being literally freer than others” (Seham 5). If all of the characters were limited to a planned script, it would make the interactions seem fake. In the case of trying to deliver a political message, it would make the discourse between characters seem very forced and like it is just meant to accomplish a political agenda. By allowing a member of the sketch to be able to have freedom on the set, interactions seem more genuine, real, and more effective in their ultimate goal of delivering a political message.

In the case of the Tina Fey and Amy Poehler sketch above, Amy Poehler, the reporter, was clearly being restricted by a script while Tina Fey was able to have more freedom to improvise. By allowing Fey to improvise, she was able to make the character she was playing, Sarah Palin, seem even more ridiculous than she could have if she was simply following a prewritten script. Fey and Poehler highlighted a flawless execution of a combination of rhetoric and improvisation within a sketch to create a powerful, satirical discourse.

Relating Saturday Night Live to rhetoric, Wayne C. Booth, an esteemed literary critic and professor at the University of Chicago, noted that “in short, rhetoric will be seen as the entire range of resources that human beings share for producing effects on others” (Booth xi). In the case of politically motivated sketches performed by Saturday Night Live, often times instead of “producing an effect” on others, they create an impression. Booth’s definition is important to our understanding of what rhetoric is because it includes all the resources that can be used to create an impression on others, which means that it includes planned discourse as well as improvisation. When used together, Saturday Night Live has shown that the two rhetorical strategies can be extremely powerful in delivering a political message in terms of satire.

Other times, Saturday Night Live simply uses planned discourse to create an effective political satire. Esteemed literary critic Michael Foucault noted that “the function of an author is to change the existence, circulation, and operation of certain discourses within a society” (Slack, Miller and Doak 80). Through the creation of different sketches, Saturday Night Live is able to change the discussion and views of citizens in society through the creation of their satire.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RetohxBENM

For example, in an attempt to ridicule the recent GOP Presidential candidate Donald Trump , Saturday Night Live created a sketch that suggested that Trump supporters were all racists, bigots, or supremacists. Although this is certainly an exaggeration, it is scorning the American people through the use of humor for even considering the idea of a Trump presidency. By comparing supporters of Trump to groups like the Nazis, they are satirically trying to influence the way people view their own decisions to vote for a candidate like Trump.

Saturday Night Live is a comedy sketch television show, yet through its use of satire created by planned discourse and improvisation, it has been able to play a role in the political sphere. Rhetoric is not just limited to an individual’s English papers in class but can be seen in many unique, influencing facets of everyday life, or at least Saturday nights.

For more examples of how SNL has used satire to critique politics and political candidates, click here.

Booth, W. C. (2004). The Rhetoric of RHETORIC: The Quest for Effective Communication. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Colletta, Lisa. “Political Satire and Postmodern Irony in the Age of Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart.” The Journal of Popular Culture (2009): 4. Online.

Cooper, Jonathan. “Top 10 ‘SNL’ Political Sketches Of All Time.” Huntington Post (2015): 1. Online.

Seham, A. E. (2001). Whose Improv Is It Anyway?: Beyond Second City. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Slack, Jennifer Daryl, James David Miller and Jeffrey Doak. “The Technical Communicator as Author: Meaning, Power, Authority.” Peeples, Tim. Professional Writing and Rhetoric. New York: Addison Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc., 2003. 80-96.

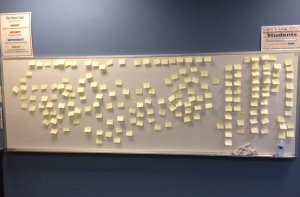

The main purpose of the brainstorm was to determine what form the new English Department newsletter would take, how it would be distributed, and what content it would include. Professor Pope-Ruark led the brainstorm and gave specific prompts to the class about the form, distribution, and content, and the class would write ideas on individual sticky notes and add them to the board. Once the idea generation was complete, the class categorized the sticky notes based on which ideas we liked the most. From there we were able to connect the dots incorporate the usable ideas into one working project

The main purpose of the brainstorm was to determine what form the new English Department newsletter would take, how it would be distributed, and what content it would include. Professor Pope-Ruark led the brainstorm and gave specific prompts to the class about the form, distribution, and content, and the class would write ideas on individual sticky notes and add them to the board. Once the idea generation was complete, the class categorized the sticky notes based on which ideas we liked the most. From there we were able to connect the dots incorporate the usable ideas into one working project