Guest post by Maggie Miller ’16

As I discussed on Monday, this week is Publishing Week. Wednesday’s post talked about how changes in technology have changed the way that we view the publishing process. On Friday, Rachel Fishman shared a history of the transition from oral to manuscript culture. In this post, Maggie Miller explains how her own experiences with publishing in ENG 311: publishing shifted her understanding of the publishing process and its relationship with text, audience, and community.

As I discussed on Monday, this week is Publishing Week. Wednesday’s post talked about how changes in technology have changed the way that we view the publishing process. On Friday, Rachel Fishman shared a history of the transition from oral to manuscript culture. In this post, Maggie Miller explains how her own experiences with publishing in ENG 311: publishing shifted her understanding of the publishing process and its relationship with text, audience, and community.

This January, sixteen other people and I took a three-hours-a-day, five-days-a-week, three-week course on Publishing. Like many of my peers, I first signed up for the course because of my recent desire to someday go into the publishing industry, as well as my lifelong desire to be published. However, the course surprised me in that it started by focusing more on breaking down what publishing (and its components: author, reader, text) were. It mimicked the philosophy, rather than English, classes I’d had in the past. However, this focus on the idea of publishing offered an opportunity to think about publishing critically and rhetorically rather than in a one-sided way. I found that my preconceived ideas of author, reader, text, community and publishing were shallow, and didn’t account for the incredible history and evolution of the phenomenon of the written word.

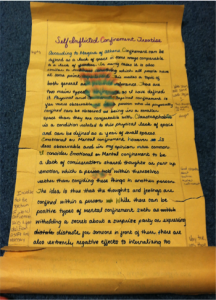

One of the main ways my thinking on these ideas was changed was by doing what we called in class, “The Manuscript Project.” Each of us mentally drafted a treatise on a various subject, then watched it travel from papyrus to an illuminated manuscript. Each step in between, however, kept in mind the restrictions and trends of the time period in which it would have occurred. For example, when we first wrote our treatises onto “papyrus” scrolls, we could not draft, erase, or use punctuation of any kind. We thus had to use different colors and sizes of letters to make the flow of our treatise clear. This part of the project was difficult in that I’m accustomed to being able to shuffle my thoughts around in a word document. This led to my scroll’s content being a bit unorganized and jumpy, as my thoughts often shifted as I was writing, even though I had made an outline beforehand. Spelling was also difficult without the use of computers or dictionaries. We could only use our neighbors as references.

One of the main ways my thinking on these ideas was changed was by doing what we called in class, “The Manuscript Project.” Each of us mentally drafted a treatise on a various subject, then watched it travel from papyrus to an illuminated manuscript. Each step in between, however, kept in mind the restrictions and trends of the time period in which it would have occurred. For example, when we first wrote our treatises onto “papyrus” scrolls, we could not draft, erase, or use punctuation of any kind. We thus had to use different colors and sizes of letters to make the flow of our treatise clear. This part of the project was difficult in that I’m accustomed to being able to shuffle my thoughts around in a word document. This led to my scroll’s content being a bit unorganized and jumpy, as my thoughts often shifted as I was writing, even though I had made an outline beforehand. Spelling was also difficult without the use of computers or dictionaries. We could only use our neighbors as references.

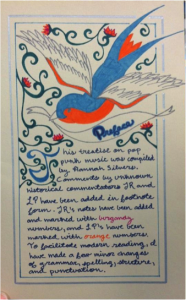

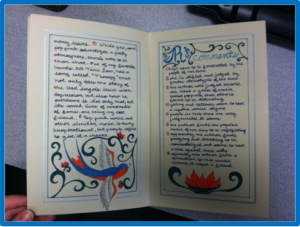

The next day, or a few hundred years later as our experiment dictated, we were given one of our peers’ scrolls: torn, water damaged and missing pieces. We each commented in the margins of two different scrolls. Fast-forward a few more hundred years. We were then scribes, charged with making an illuminated manuscript out one of the scrolls, and incorporating both sets of comments into the text in some way. The final product was “bound,” illuminated, and prefaced.

The project forced me to not only realize that author, audience, text, community and publishing are not static ideas, but also encouraged me to look into what cultural and historical elements affected previous views of the ideas.

One example is my view of when a text is considered “published.” When I first responded to the “Big Questions,” I mentioned, almost as an afterthought that, “a text is published when it is made available to the public without further intention of the author to change it.” I add that last caveat to avoid the assumption that something given to a group of people (the “public”) for revision or some other editorial purpose could be considered published (in my mind, that would not be considered a published text, although it was made available to a select public).” While I meant for this to be a purely modern idea, based on the fact that paper and other writing utensils are so readily available now that editing and reviewing another person’s work before it is published is common and expected, I realized with further research into textual history that it is relevant in many more contexts than my modern one. For instance, until very recently, writing utensils were scarce, and the author had no control over their text once it was written. So whether or not the author has intention to change it has less importance. This was evidenced in the fact that we could not draft our treatises when writing them on papyrus. There was a permanence to every word, making authors more careful, audiences more reverent, and texts more sacred.

One example is my view of when a text is considered “published.” When I first responded to the “Big Questions,” I mentioned, almost as an afterthought that, “a text is published when it is made available to the public without further intention of the author to change it.” I add that last caveat to avoid the assumption that something given to a group of people (the “public”) for revision or some other editorial purpose could be considered published (in my mind, that would not be considered a published text, although it was made available to a select public).” While I meant for this to be a purely modern idea, based on the fact that paper and other writing utensils are so readily available now that editing and reviewing another person’s work before it is published is common and expected, I realized with further research into textual history that it is relevant in many more contexts than my modern one. For instance, until very recently, writing utensils were scarce, and the author had no control over their text once it was written. So whether or not the author has intention to change it has less importance. This was evidenced in the fact that we could not draft our treatises when writing them on papyrus. There was a permanence to every word, making authors more careful, audiences more reverent, and texts more sacred.

Another major thing that was affected by the undertaking of this project was my understanding of authorship. Originally, I wrote that, “An author is the person who not only writes words but creates new phrases, ideas, etc. using those words. The author relates to the text in that it is their product. Although usually there are other influencers of the text besides the author such as editors or reviewers, the author is the one who supplied the bulk of the writing and the original draft.” However, for much of history this definition could not apply. Many authors’ works were made up of a majority of quotes and ideas from previous scholars. This was considered honorable and made the text more authoritative. Thus, the “author” of a text often wasn’t the original writer, but a compiler, or someone who made meaning out of previous ideas and subsequent comments. We saw this in our own projects when we had to incorporate other students’ comments into our final manuscripts. It was this novel idea that made me more receptive to and understanding of Bonaventura’s 5 different categories of “author.”

My understanding of community was also affected by this project. I first wrote, “A community is a group of people who are united by some shared quality, interest, value or other element. For example, a neighborhood is a community in that the residents share a location. A group of blog-followers could also be considered a community, even if they’ve never met in person, because they share an interest and understanding of a specific blog.

My understanding of community was also affected by this project. I first wrote, “A community is a group of people who are united by some shared quality, interest, value or other element. For example, a neighborhood is a community in that the residents share a location. A group of blog-followers could also be considered a community, even if they’ve never met in person, because they share an interest and understanding of a specific blog.

Texts have an incredible impact on community, in that they could be the item which unites the group of people, they could be a commentary on the union, or they could be something which, due to content, further strengthens the bond of an existing community.” While this basic definition is, in my opinion, for the most part accurate, I did not think about the evolution of community throughout the ages. When writing our treatises on papyrus, we were allotted very little resources. For me, the hardest thing was that I had only the people in my class to use as a dictionary. This led to a greater understanding of the small, isolated, and limited communities in which some of these people were writing. That in turn led to a greater understanding of the small, isolated, and even more limited (in that they were illiterate) audience for most early texts. Such revelations helped me justify the incredibly reverence that the ancients had for texts, as well as their rarity and power.

Overall, I found my ideas of the “Big Questions” of publishing very much affected by the completion of the project. Whether the new perspective of the historical fluctuation of the ideals or the realization of the impact of cultural contexts, the project helped me further along in my understanding of publishing-related ideals, and will help me as I seek to find my own place in the modern world of publishing.

Follow

Follow