How can your organization improve your life as a humanitarian worker?

A final question

A final question

The final, open-ended question on the survey asked, “What are your thoughts about what your organization could do to improve your life as a humanitarian aid or development worker?”. At the end of a 43 item survey, this question generated 53 responses, 35 from females and 18 from males.

Below I have included over two dozen responses, broken down into themes. The comments I make reflect some of what I have learned from the entire survey.

Need for attention to the emotional strain of the job

This first set of responses addresses the emotional strain of doing humanitarian work. As one respondent put it, “This line of work is very demanding, long hours, weekends, very little support, fatigue. It effects the physical as well as mental health.”

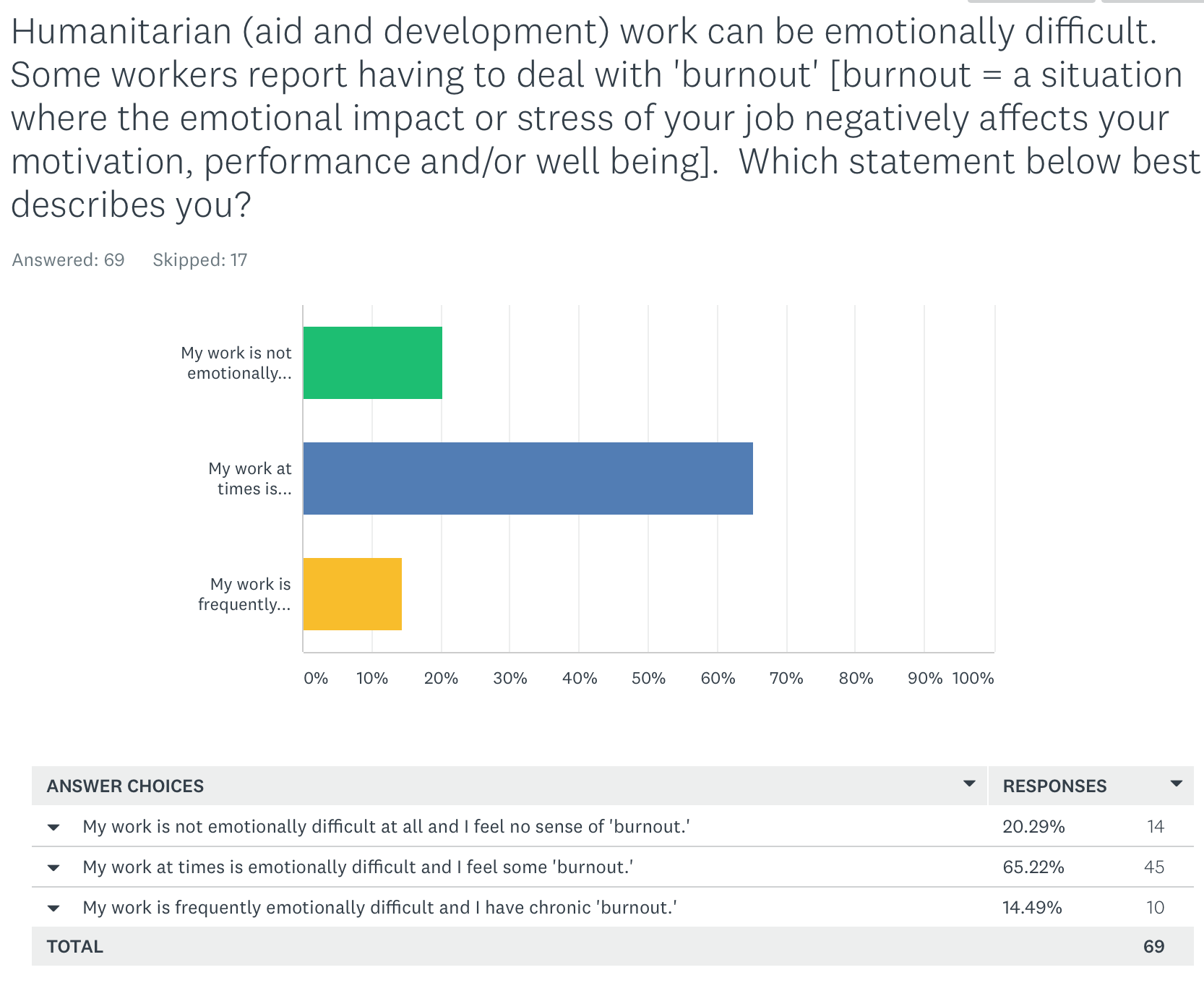

Question 28 on the survey asked, “Humanitarian work can be emotionally difficult. Some workers report having to deal with ‘burnout’ [burnout = a situation where the emotional impact or stress of your job negatively affects your motivation, performance and/or well being].” Eight of ten respondents indicated that their work can be emotionally difficult, most indicating that “My work is frequently emotionally difficult and I have chronic [or moderate] ‘burnout.’

What Jordanian based INGOs and NGOs can do to address this is straightforward and told in the responses below.

- “More self-care activities especially aid workers who spend 98% of their time in the field.”

- “More psychosocial support for workers, and a chance to do fun activities every once in a while.”

- “Staff care, paid psychiatric clinic sessions.”

- “Adding psychologist to the medical insurance.”

- “Invest more in the psychological side of the staff.

There is significant attention sector-wide being paid to the issue of staff mental health. Here Brendan McDonald cites many of the relevant studies and offers a list suggestions on how the sector can improve.

In sum, the above comments indicate that Jordanian workers have unmet psychosocial support needs.

Calls for equal status, capacity building, and opportunity

Virtually any sector insider is well familiar with the issue of national versus international staff compensation packages, and everyone seems to have their own opinion on the matter. I recommend a close reading of this essay by my colleague J for some sober, sound advice and perspective on this matter.

In a series of posts (here, here, and here) I describe and comment on survey results which examined this issue in detail.

The Society for Human Resource Management comments on “Designing Global Compensation Systems“, but this document, comprehensive as it may be is, predictably enough, only from the perspective of the ‘expatriate’ assigned to international posts. This short essay by Mark Canavera does a good job of introducing the history behind the international versus national humanitarian worker compensation disparities.

All that said, here are some of the respondent comments related to this theme.

- “Equal opportunities would be a great topic to work on… and of course RESPECT!!! my culture and experience is something valuable and needed to be into consideration.”

- “More appreciation, higher salary, giving the Jordanians the chance to be in higher positions that do no need to be foriegns, عقدة الاجانب.”

- “To be more appreciated when it comes to salaries and promotions.”

- “Build my capacity and treat me as an equal.”

- “Meet the capacity building aspects which is fit to the organization and personal development goals. As an INGO worker having a fix contracts will give the feel of positivity and stability.”

- “Better career paths.”

- “BUILD CAPACITIES we miss it especially in the specialized field we are working on.”

- “Invest more in employees and get them on career paths.”

- “To be treated the same as international staff, medical, housing and salary wise.”

- “I think there is a gap between the higher management and the staff. Improving the humanitarian staff by giving them more stability rather than searching for new blood specially after the staff burned out.”

- “It is very important that the benefits and competitive salaries are offered equally to everyone regardless of their nationality or background, as long as they can get the job done well. This is where the fair process starts. National staff need to be represented at a senior, decision making level. In my organization, no national is part of the core-management team, neither is any allowed to be (as per the internal regulations and protocols!).”

- “Job Security, you spend enough years to not yet get a retirement pension. Some sort of retirement plan that could provide you with retirement away from Jordan Social Security policy that needs you to work up to 60 yrs old to get your pension.”

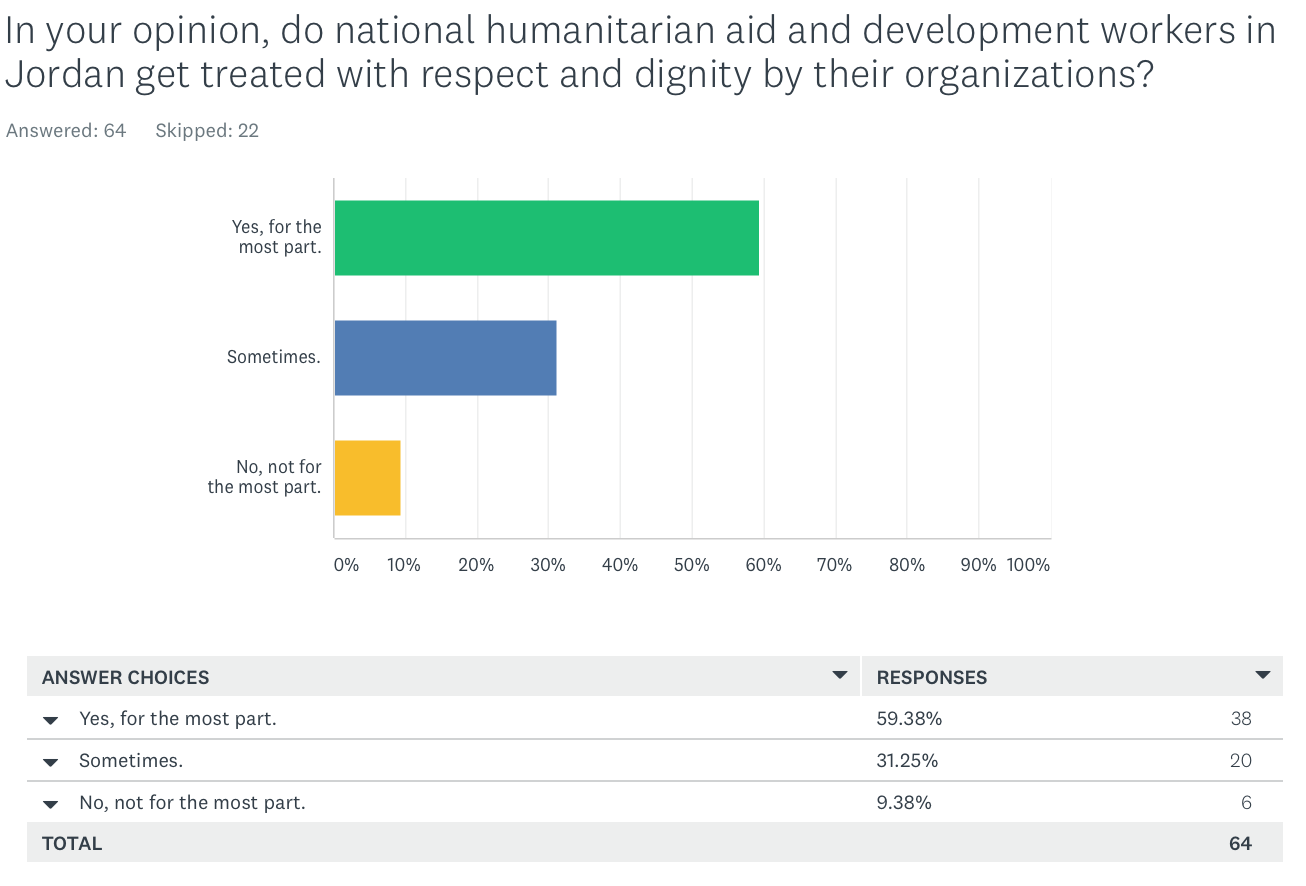

In the most negative light, the perceived gap between the treatment of national versus international staff has, in the words of one interviewee, a ‘caste-like’ nature to it. In previous posts (see above) I have detailed various dimensions of this issue and, given what I understand -at least for the foreseeable future- most of the above concerns will remain largely intractable issues.

Listening and amplifying voices

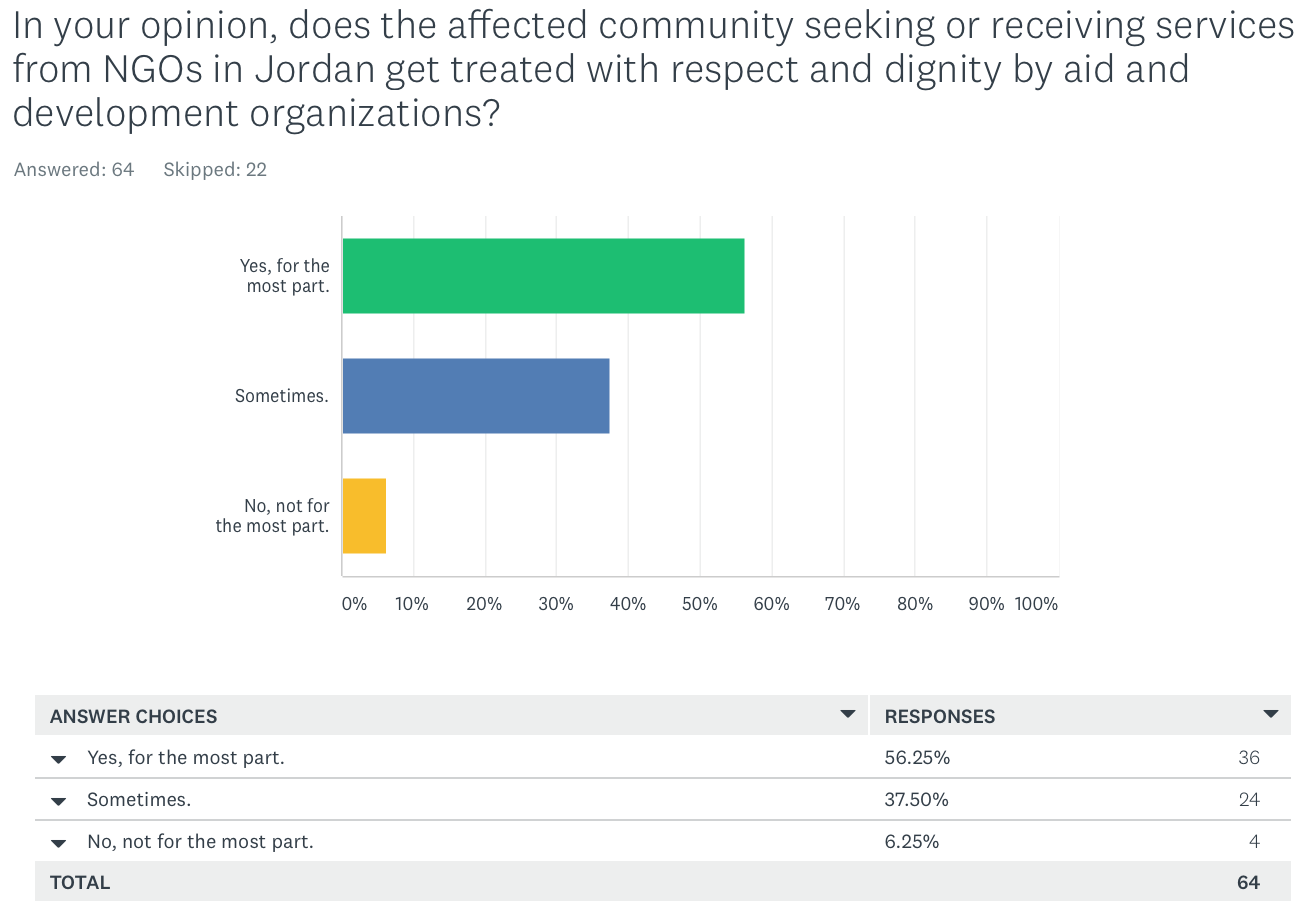

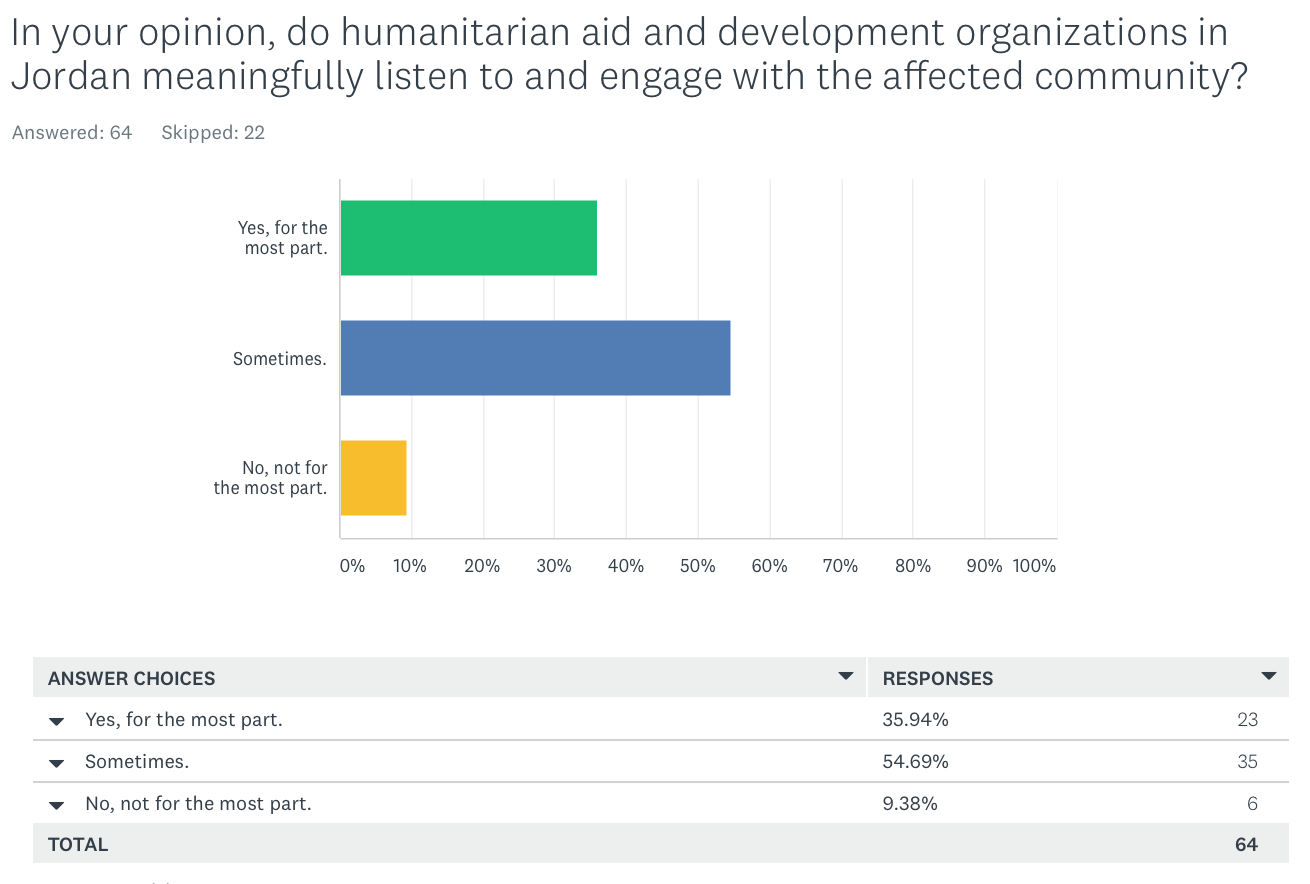

This next series of comments raise the issue of listening to the affected community. As the critical connecting mechanism between the donors and those being assisted, humanitarian workers are sensitive to what does and does not work. Using tried and true ‘recipes’ from other parts of the world seems to make sense, but what the humanitarian who offered this first comment is arguing is these approaches need to be more carefully retrofit to the Jordanian situation by using the input from both national workers and members of the refugee community.

- “Aid and livelihoods alleviation is best done when conducting continuous participatory approach, engaging the affected population with the designing, planning and implementation of the programs. Amplify their voice and reflect their own needs and concerns onto the program, rather than parachuting ready recipes on them, particularly those coming from Africa!”

- “Be more assertive with donors. Try to live up to its values more honestly, and stop trying to emulate big organizations at the expense of our values.”

- “Better capacity building, listen more to local workers, more trust in the local capacities.”

- “Open a discussion channels, having a personal developments plans, taking in consideration the people in the field opinions while preparing for the new proposals.

In sum, and again not news, listening = good. Yes, it bears repeating: one can never over-stress the fundamentals in any context. We need all pay constant attention to what is being said -and not said- by all with whom we interact.

Concluding thoughts

The three themes above -psychosocial support, equity, and listening- are all important and, I believe, are generally recognized and acknowledged by most in the sector. Work is being done both in Jordan and elsewhere by both individuals, INGOs and NGOs, and sector-wide by umbrella entities like ALNAP and REACH. Meaningfully moving the needle in a positive direction on these issues is an ongoing and necessarily slow process, and many well intentioned people are pouring creative energy into imagining and enacting changes.

generally recognized and acknowledged by most in the sector. Work is being done both in Jordan and elsewhere by both individuals, INGOs and NGOs, and sector-wide by umbrella entities like ALNAP and REACH. Meaningfully moving the needle in a positive direction on these issues is an ongoing and necessarily slow process, and many well intentioned people are pouring creative energy into imagining and enacting changes.

But.

But in a world where most humanitarian responses are chronically and in many cases critically underfunded, where do the resources for proposed changes come from? How do you convince donor entities -themselves being held accountable for ‘using money efficiently’- to agree to allowing scare resources to be used on ‘non-critical overhead’?

As always, please contact me if you have any feedback, suggestions, and just want to offer some snark.

Post script

I have deep appreciation for all the time taken by every respondent who offered their opinions and perceptions. My thanks to each one.

One respondent’s comment made my day. Indeed, improving the lives of Jordanian humanitarians was the primary goal of this research. She said,

“Thank you for your survey, I hope it will improve the humanitarian workers’ situation in Jordan.”

Follow

Follow