Post updated 21 May 2018 with Jordanian-Filipino comparison data.

“I would be surprised if any national believes that “expats” don’t see themselves as superior to nationals, regardless of the experience or the grade! NOT all internationals though are the same, some are very humble and natural. However, condescension is very prominent among international staff towards nationals, whether in subtle, patronizing behaviors or rude and explicit ones.”

-veteran male aid worker

Jordanian voices on relationship between ‘international’ and ‘national’ staff, Part II

Tell me how you really feel

Part I in this series of posts explored the results from two questions probing the relationship between ‘international’ and ‘local’ aid workers. A third survey question in this section regarding the relationship between international and ‘local’ staff

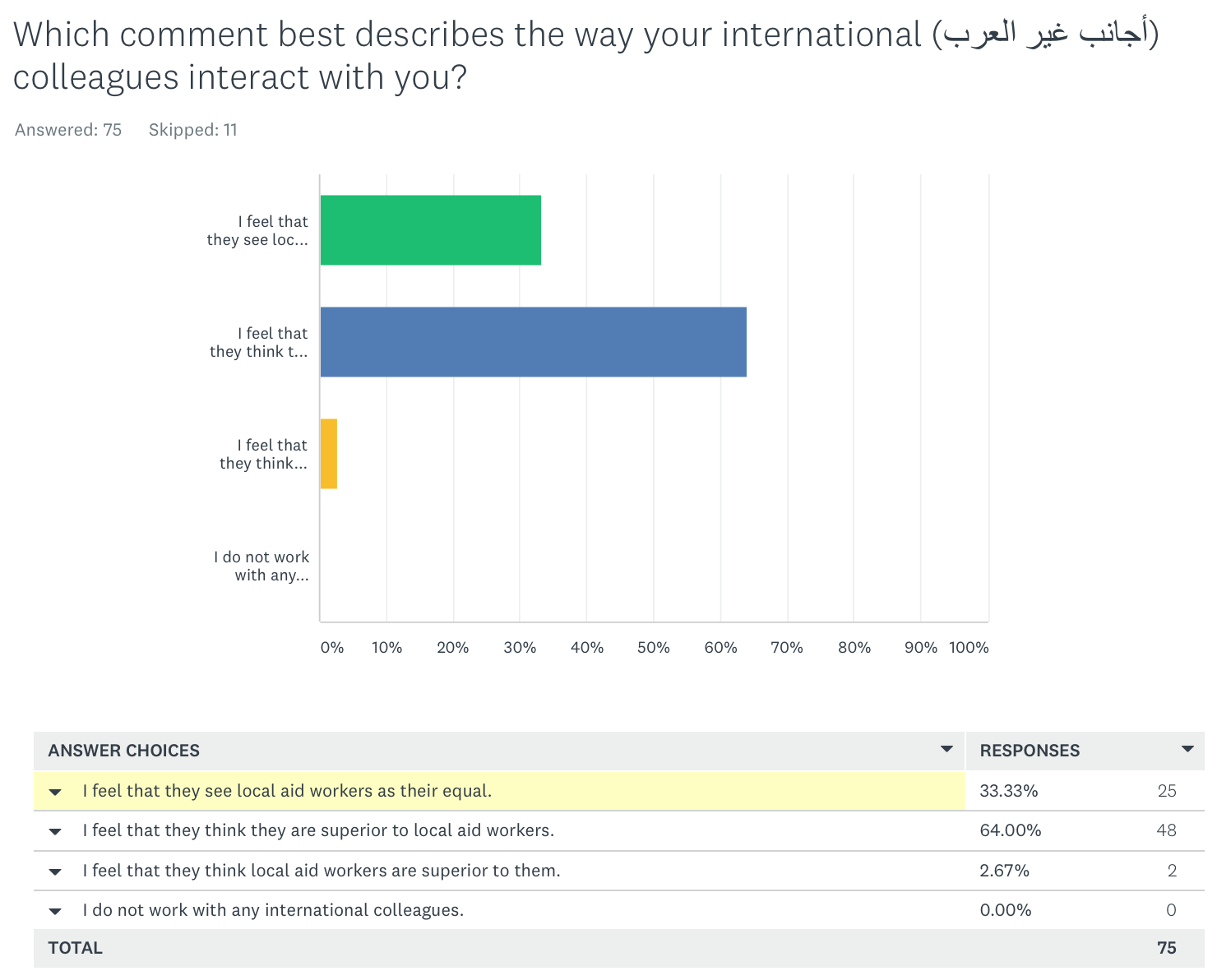

asked, “Which comment best describes the way your international (أجانب غير العرب) colleagues interact with you?” The categories offered forced respondents to characterize the power dynamics in their relationships with ‘expats.’

By an overwhelming margin -nearly two thirds -64%- Jordanian aid workers felt that their international colleagues believed themselves superior to local staff, thus leaving only one in three surveyed thinking that expats see local aid workers as their equal. The comments that some wrote add detail. One veteran male aid worker stated,

“I would be surprised if any national believes that “expats” don’t see themselves as superior to nationals, regardless of the experience or the grade! NOT all internationals though are the same, some are very humble and natural. However, condescension is very prominent among international staff towards nationals, whether in subtle, patronizin g behaviors or rude and explicit ones.”

g behaviors or rude and explicit ones.”

This question -indeed most questions on the survey- force respondents to make broad generalizations. In any array of humans there will be a wide distribution of traits, as phrased just above, “NOT all internationals though are the same.” Yes, but those with the most negative attributes tend to be highlighted in the comments section of an anonymous survey.

In my previous research on Filipino aid workers the same question was asked. Among those respondents ‘only’ 44% felt international aid workers ‘think they are superior to local aid workers.’

Ethnocentrism defined

This next respondent comment brings up some very real issues of perspective and even ‘competing’ ethnocentrisms.

“The majority of the international colleagues I’ve worked with have dispensed a sense of superiority especially because the sector’s structure places them in places of superior power. The opinions of “local” aid workers are less important, less “sound”, and less “logical” to them. They miss the very obvious fact that different people come from different epistimologies. Often times — especially in inter-agency meetings, people argue from totally different universes of discourse, missing each others’ point and ultimately decisions are made by the most powerful (international staff).”

How one knows the world -their epistemology- is guided by many factors, the most dominant of which is their home cultural context. In, as mentioned above, inter-agency meetings there is one language being spoken, invariably English, in many cases not the first language of many in the room. Though all parties may literally be speaking the same language, I’ll assert that there are important and even critical nuances in meaning that are frequently misunderstood by all parties. We all know -but frequently forget or ignore- that languages do not translate word for word into other languages, and that shades of meaning are lost and gained with every translated exchange. Indeed, people typically are arguing from “totally different universes of discourse” and, given the power dynamics in the room it would not be unusual for the operative interpretation of meaning to be made by the international colleagues in the room, that is, the ones who most typically wield the most power.

Invoking here the word ‘ethnocentrism’ seems appropriate, and this exact sentiment is captured by this young female Jordanian,

“The international workers are of a community of their own, and many do look at locals in a superior manner not only professionally but culturally.”

In very basic terms, ethnocentrism looks like this: If A ≠ B ∴ A > B; if some other person or culture is different from mine, by default mine is superior. Its opposite, if A ≠ B ∴ A ≠ B, is how we all aspire to function, wanting to be culturally relativistic. As the Javanese told anthropologist Clifford Geertz long ago, “Other fields, other grasshoppers.” But being ethnocentric is our default mode as humans, and it takes constant work to check how our cultural lenses are functioning in every interaction in order to achieve true cross-cultural awareness and acceptance, i.e., cultural relativity.

One young male put it succinctly,

“I believe there is sometimes a gap in understanding each other potentials and deeds.”

The “gap in understanding” likely comes from deeply embedded cultural assumptions being made by all parties and is being masked by the fact that everyone is speaking the same language, smiling and nodding at each other while simultaneously -though typically unwittingly- not fully understanding what has just been understood by the other.

Do international workers listen to local advice?

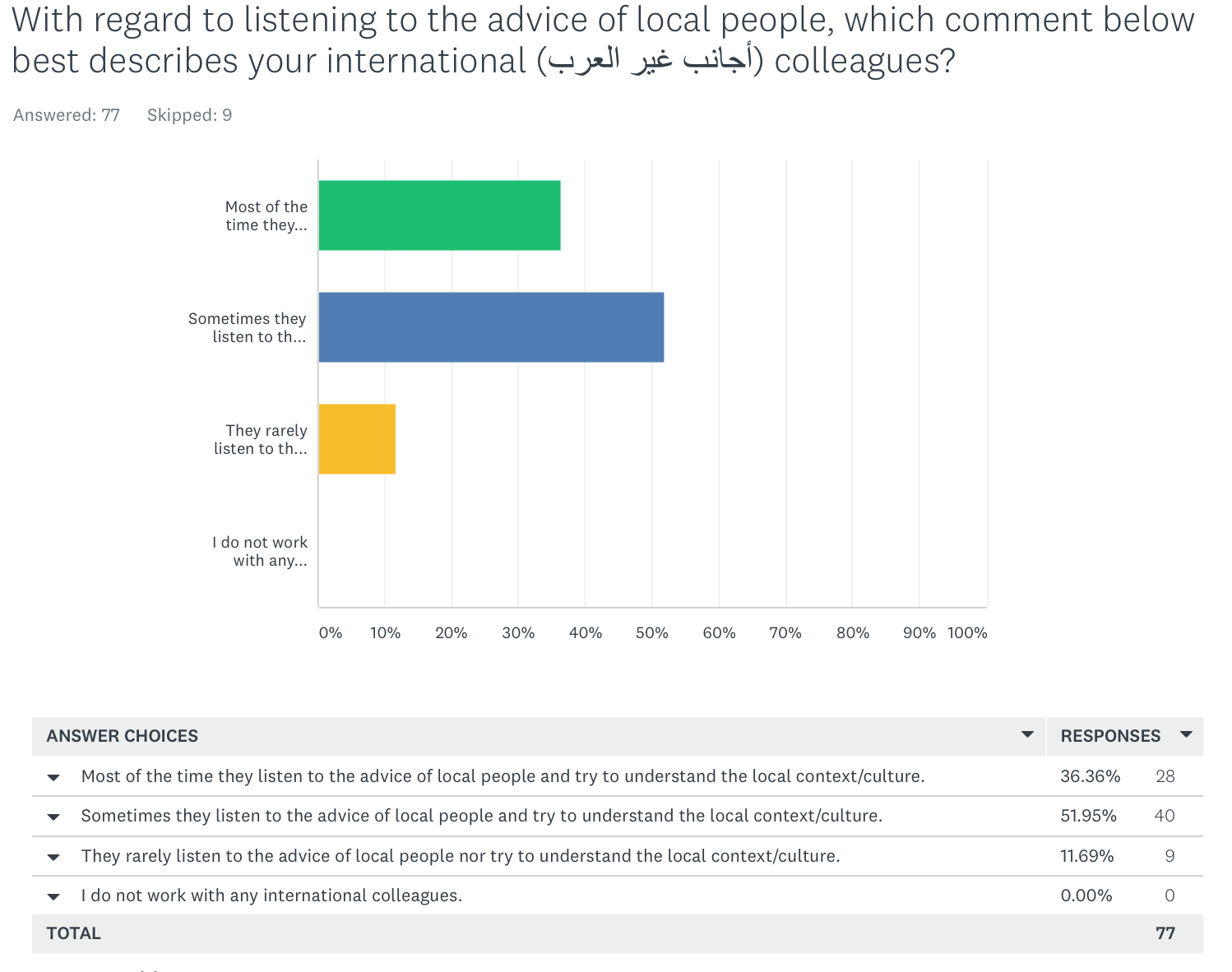

Given the results of the previous questions that paint ‘expat’ aid workers in somewhat negative light, the results of the next question extend and deepen this view. The next questions asked, “With regard to  listening to the advice of local people, which comment below best describes your international (أجانب غير العرب) colleagues?”

listening to the advice of local people, which comment below best describes your international (أجانب غير العرب) colleagues?”

Over a third of the respondents observed that “Most of the time they [international staff] listen to the advice of local people and try to understand the local context/culture.” That leaves nearly two thirds believing that international colleagues only ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’ listen to the advice of local people nor try to understand the local context.

This comment called out a flaw in the response categories offered, clarifying that there is a

“Difference between listening to beneficiaries (which they do), and listening to the opinions of local coworkers (which is not always the case).”

This next comment repeats the common theme that in any array of people there will be those on various places on, in this case, a cultural sensitivity continuum.

“Sometimes internationals respect cultural sensitivities, and abide by the advice of nationals because they trust that nationals know better. But sometimes they come up with all their analyses and breakdowns of the context in Jordan/the Middle East in the most stereo-typically degrading manner and without much logic.

Again, comparing Jordanian and Filipino voices on this question is interesting. While 64% of the Jordanian’s surveyed thought that international aid workers only ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely listen to local people, the Filipino number for the same question was 57%. The data indicate that by a noticeable margin Jordanian aid workers are more critical of the ‘expat-local’ relationship than their Filipino counterparts.

A gender difference?

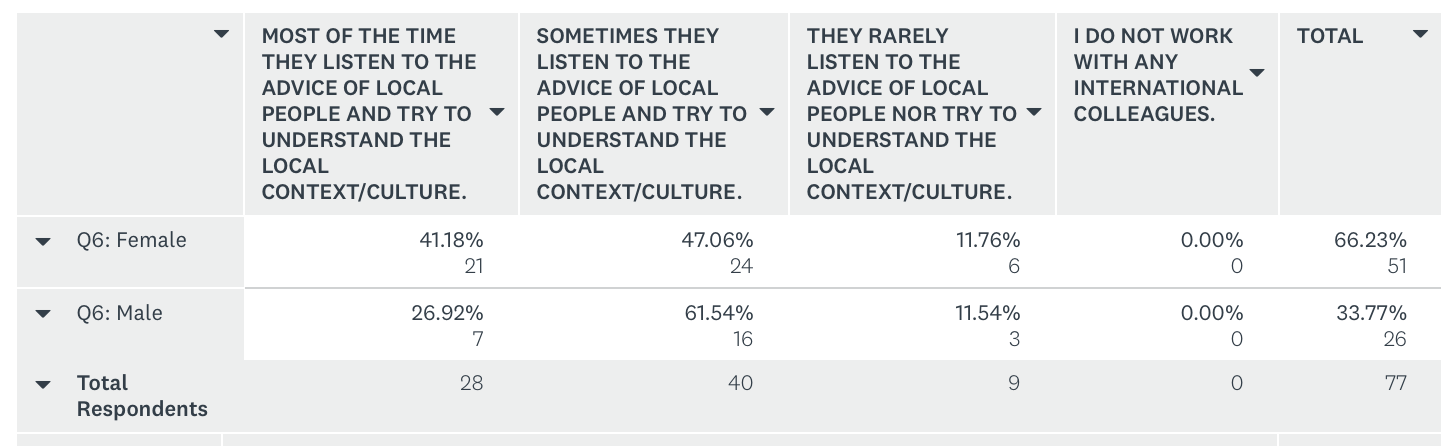

In general throughout the survey I found that females were more likely to comment, and when they did comment to write more detail. The numbers below are so small no conclusions can be drawn, but  breaking down the data from this last question by gender indicates that more research in this direction may be warranted. As you can see, though the percentages are very similar for “rarely listen”, males appear to have a much more critical view of the ability of their international colleagues to listen to locals.

breaking down the data from this last question by gender indicates that more research in this direction may be warranted. As you can see, though the percentages are very similar for “rarely listen”, males appear to have a much more critical view of the ability of their international colleagues to listen to locals.

Looking forward

My next post will hit on the perennial issue of compensation disparities between ‘expats’ and ‘locals.’ Stay tuned. In the meantime, please email me if you have comment or question.

Follow

Follow