“One man’s corruption is another man’s wealth redistribution system. I find it hard to judge others on this.”

–26-30yo female

“Corruption is the biggest cause of poverty. If you are in aid, you deal with corruption.”

–36-40yo male

“Corruption is there throughout the developing world (and the developed world but on a less blatant scale). We are often asked or hinted to pay bribes lest our applications for import, registration, visas gets put to the bottom of the pile. We don’t because we have to account to our donors. But we did in one case buy drivers licenses as the ‘process’ was going to take about 6 months.”

–female veteran aid worker

Cancer of corruption or the culture of corruption?

Difficult to define

How can we define, discuss and analyze the endemic social phenomena of corruption? How do aid workers understand and deal with corruption?

I will agree completely with the many who will point out that corruption is impossible to definitively operationalize and that cultural context, history, point of perspective, motivation, etc. are all factors. In  fact I’ll argue that the term itself is a semantic land mine charged with power/Western-centric thinking. Not the least of the complications regarding formulating one’s opinion on this topic is the fact that in many cases what is unethical can also be legal.

fact I’ll argue that the term itself is a semantic land mine charged with power/Western-centric thinking. Not the least of the complications regarding formulating one’s opinion on this topic is the fact that in many cases what is unethical can also be legal.

Defining corruption must include the fact that, well, it’s a matter of definition, and we need to understand the forces driving that definition. To quote a German thinker of some note, “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas…” Just as term child abuse did not come into common use in the West until recently (mid 20th century), I would argue that as a lived phenomena is has existed for as long as there have been children. The same goes for corruption. My generic definition of corruption would be that it is a form of dishonest or unethical conduct by someone or some organizational entity entrusted with and/or structurally in a position of authority or power. Though since Greek times this idea has been bandied about, I submit that much like my example of child abuse, corruption has always been with us but not recognized, labeled or defined as such.

Begun in 1993, Transparency International has earned a reputation for generating both useful data on corruption internationally and in playing a part guiding policy changes that address this issue head on. Their efforts have done much to raise the level of awareness about corruption internationally, though much remains to be accomplished both in terms of refining the measures and in being more inclusive in terms of differentiating the units of analysis that engage in corrupt behavior. The ubiquitous slippery slope between ‘business as it has always been conducted’ and overt corrupt actions remains, and in many cases around the world there will be push back from those in power if ‘legal’ actions are termed corruption.

corruption internationally and in playing a part guiding policy changes that address this issue head on. Their efforts have done much to raise the level of awareness about corruption internationally, though much remains to be accomplished both in terms of refining the measures and in being more inclusive in terms of differentiating the units of analysis that engage in corrupt behavior. The ubiquitous slippery slope between ‘business as it has always been conducted’ and overt corrupt actions remains, and in many cases around the world there will be push back from those in power if ‘legal’ actions are termed corruption.

Regarding corruption, the trope “no rules, just right” captures my perspective in that if by “just right” we mean that which is fair and just to all based on some universal understanding that the lives of all humans have equal value and should be treated fairly. I am reminded of various ethological studies, primarily among primates, indicating that we have inherited a deeply wired sense of fairness and, by extension, that we are all capable of sensing abuse of power, i.e., corruption. Point being that corruption may not be entirely a cultural construct, adding yet another level of nuance to our understanding of this term.

This respondent added even another, critical dimension to the semantic soup concerning corruption.

“Corruption happens but does not affect me. Internal audits are quite strong and cases do happen. What is missing (for UN organizations at least) is the same vigilence against prostitution and sexual harassment.”

An argument can be made that popular culture definitions of corruption imply an almost myopic focus on misappropriation of money or materials, though most people would include favoritism, cronyism and nepotism. Is sexual harassment an abuse of power and thus a major form of corruption? Absolutely. Transparency International has a good -and growing- data base of information on this topic and elsewhere on this blog I have addressed the topic of how gender impacts the role of aid workers.

Survey says

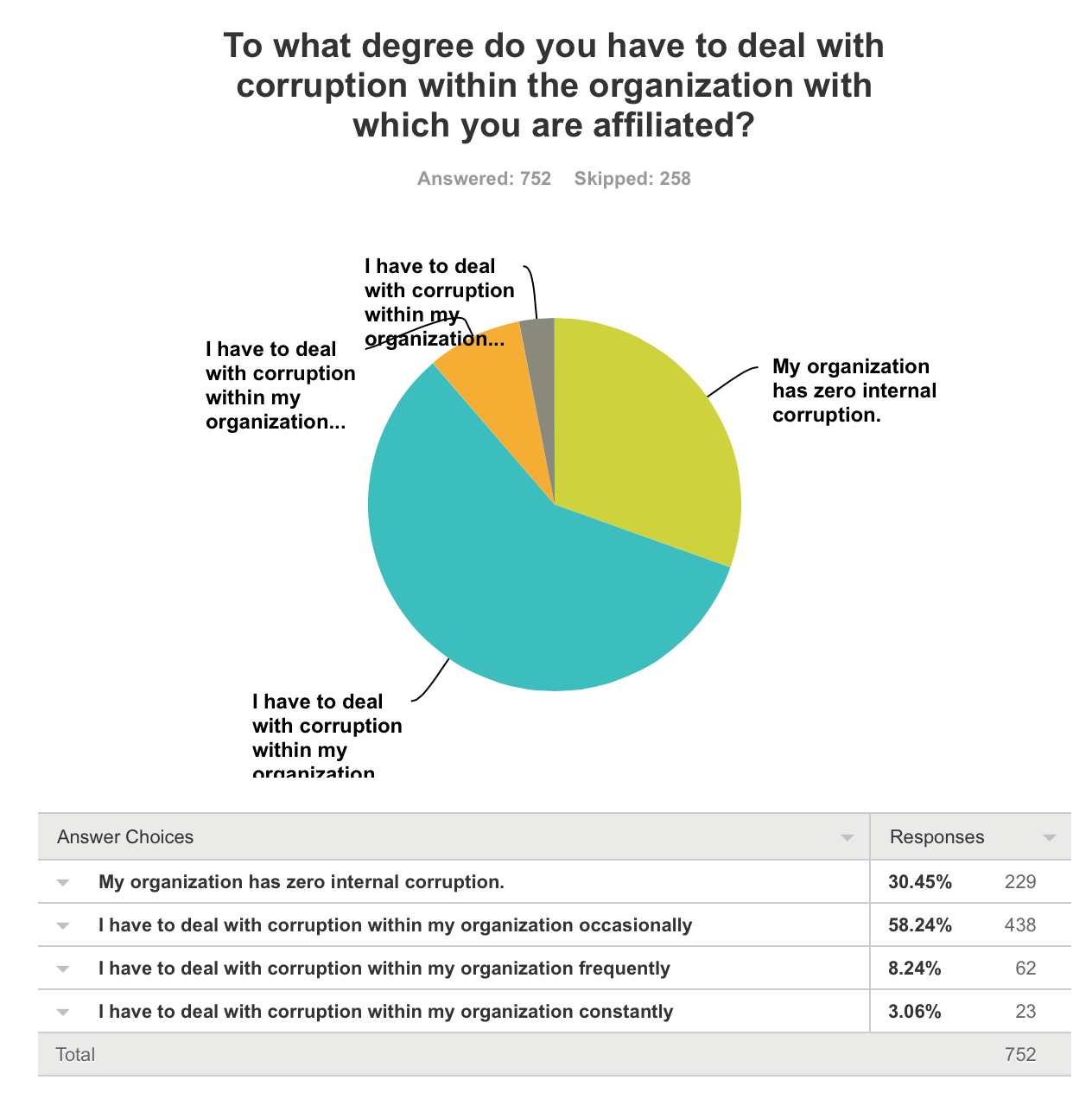

Let’s drill into what aid workers had to say about the issue of corruption, first looking at the quantitative data. We asked two closed-ended questions, first regarding corruption within their current organization and then in the context of the sector in which they are currently working. Here are the data in response to the question, “To what degree do you have to deal with corruption within the organization with which you are affiliated?” As you can see, about 70% reported having to deal with at least some corruption.

My wonder as I looked at these data was the mindset of those 30% that responded that “My organization has zero corruption.” Drilling down into the data I found that among those who reported being affiliated with UN based organizations were only slightly less likely to report zero organizational corruption, and the percentages ranged very little among all the different affiliation groups. Given the broad definition of corruption that I outlined above, I frankly have no explanation for these results other than poor question construction. As one respondent put it,

“I work for the UN where unethical behavior is a constant.”

Another put it this way,

“If someone response zero corruption, could you please publish the name of that institution so I can apply? Corruption exists within society and in situations of potential power abuse [it] flourishes…”

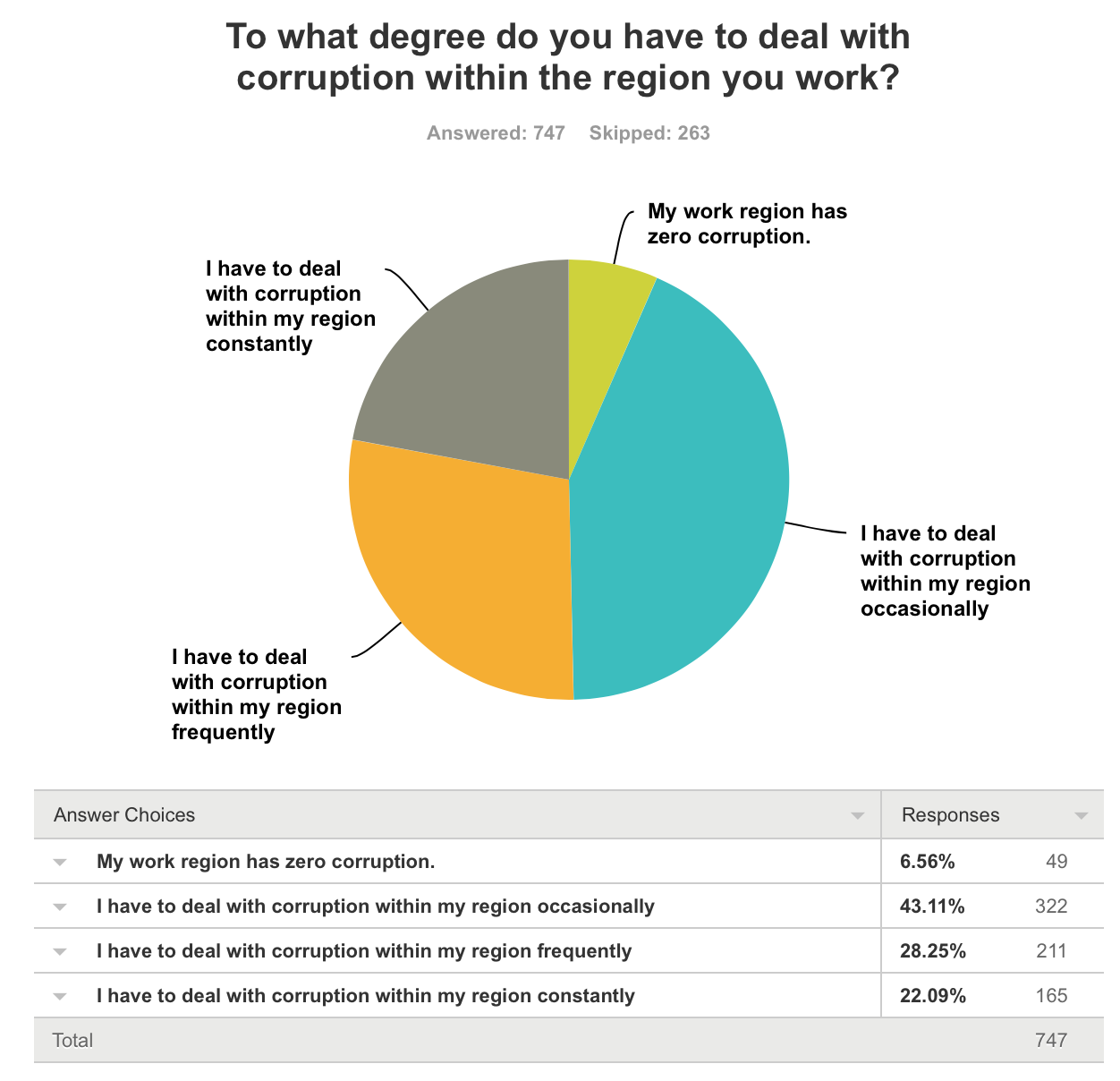

The second closed ended question on corruption asked, “To what degree do you have to deal with corruption within the region you work?” As you can see below, the problem of corruption appears to be pervasive and serious, with 93% of the respondents indicating they have deal with corruption at least occasionally. That over a fifth of the respondents saying that they have to deal with corruption “constantly” is telling.

Though the quantitative results are interesting, it is the narrative responses that paint a much more complex picture, one with many nuances.

Narrative voices on corruption

Just after the two closed ended questions on the survey discussed above the following prompt was given, “Please use the space below to elaborate on the questions above related to corruption.” There were a total of 313 narrative responses, many providing some useful points of departure.

Affirming the most recent rankings of Transparency International, here are some representative responses getting directly to the point, indicating simply that dealing with corruption is a given within certain countries.

- “Uganda…need I say more?” (TI ranking 139/167)

- “I live in Cambodia. It’s all corruption.” (TI ranking 150/167)

- “I work for an Iraq country office. Everything is corrupt.” (TI ranking 161/167)

- “It is embedded in the Liberian culture.” (TI ranking 83/167)

- “Somalia. That is all.” (TI ranking 167/167)

Unpacking aid worker views on corruption

These next thoughtful response captures several themes that merit close attention:

“Where do I begin? One of the problems of BIG AID is the endemic corruption it carries with it. In poor countries, lots of money connected to faceless donors creates a magnetic field around it which distorts markets, expectations and integrity. Battling this is a full time job and demands a canny understanding of the context. This demands battle hardened veterans who stay around and can manage the corruption issues. However, the nature of humanitarian work is one of constant turn over, so this is an issue.”

The idea that large sums of money or resources simply ‘distort’ the equation in many ways and humans being, well, humans, there is a natural tendency to be tempted to pilfer from what may at times appear to be limitless resources. The antidote to this suggested above, “battle hardened veterans” who manage corruption is undercut by the sector wide high run over rate. Younger, less experienced staff come in and can be easily pulled into illegal or corrupt practices especially when there is a strong need to be culturally sensitive and ‘fit in.’ As one respondent put it,

“Indonesia has a lot of corruption. Not just bribes, but more “personal favors” that they don’t view as corruption, so it’s hard to battle.”

“Corruption is a way of life here and most of the local authorities see it very differently than in the West. national staff get a lot of family pressure and struggle to explain how things are done differently.

The slippery line between corruption and standard cultural practice was made evident in many comments. This is especially true in the case of favoritism, cronyism and nepotism.

“Corruption means different things to different people. Family hiring and ‘bak-shish’ are just the way of doing business here in the Middle East.”

Let’s first look at family hiring and then ‘bak-shish.’ As one young female aid worker put it, “One man’s corruption is another man’s wealth redistribution system. I find it hard to judge others on this.” If you have a job and are in a position to hire people or to award contacts then in many countries you are bound by cultural expectations to “redistribute the wealth” in order to help out family and friends. This is a textbook example of role conflict where the ‘father’ role is expected to override the ’employee’ role.

And what of nepotism? It may be hard to convince some from the Global South that George H. W. Bush didn’t hand down his Presidency to his son George H. Bush, and that Bill Clinton is now attempting to pass the Presidency to his wife Hillary Clinton and, in an earlier generation, President John Kennedy appointed Kennedy as Attorney General because he was his brother.

As for ‘bak-shish’ as a way of doing business, yes, tipping someone willingly for good or extra service seems to be fairly ubiquitous not just in the Middle East but elsewhere around the world. But when does ‘bak-shish’ morph into ‘rashwa’ or asking for bribe? In pre-invasion Iraq ‘rashwa’ existed, but asking for a bribe was a punishable -and punished- offense. The current situation in Iraq is that now there is no shame in demanding ‘rashwa.’ The cultural disintegration caused by war has led to this situation. One must ask to what extent has massive and at times sloppy monetary and resource aid -both from the US military and perhaps less so from the humanitarian aid world- contributed to that ugly cultural shift. Aid workers come into contexts like this and face a difficult task not becoming enmeshed.

And with this example a fairly obvious conjecture can be put forward: as cultures face disintegration from disasters -both human made (e.g., war) or natural is it inevitable that the level of corruption will rise? In the broadest possible terms, social order, which in general can tap down and control our baser tendencies, can generate corruption muting norms, and any breakdown in the social order will lead to a breeding ground for the ill-use of power all levels. Just a thought.

And with this example a fairly obvious conjecture can be put forward: as cultures face disintegration from disasters -both human made (e.g., war) or natural is it inevitable that the level of corruption will rise? In the broadest possible terms, social order, which in general can tap down and control our baser tendencies, can generate corruption muting norms, and any breakdown in the social order will lead to a breeding ground for the ill-use of power all levels. Just a thought.

This next comment summarizes several points made above and raises a new one regarding “fixers”:

“Corruption is a tricky term. Internally there are the no-bid contracts and consultancies dished out to friends. None of it violates the letter of the law or policy, but it certainly feels unethical. In country its just the little things, traffic cops, pushing government processes along. Most of this is anecdotal as, with most organizations we use ‘fixers’ to navigate local bureaucracy. Of course local practices vary widely, in much of Africa I am pleasantly surprised but how little major corruption I am confronted with. Alternatively, in Afghanistan, the utter shamelessness of it was exhausting. This was probably as much a function of the massive sums of money floating around as it was culture.”

If you use local “fixers” how much can one know about how they are navigating the terrain, especially in situations where language is a major factor?

Yes, I am bringing up Easterly

The following observation has a clear “Easterlyesque” tone (as in William Easterly) and questions the impact of the entire development sector.

“When it comes to “development work”, then they have no excuse for the rampant corruption, which I have witnessed. I really feel that development aid of the big dollar variety has in many places really created corruption, dependency and undercut local efforts at self-development. It’s almost as if this industry was in the business of keeping itself busy under the myth of lifting people out of poverty.”

This respondent, a thirty-something female, further critiques the development sector and waxes poetic about the nature of the human condition, imperialism and the fine semantic distinctions that arise when talking about corruption:

“In the organisation, it is bloated with money and many people simply gorge at the trough of development aid. I am thankfully removed from this in my field, I have little reason to interact with others in my organisation. I do see the old boys network everywhere, the British upper middle classes in particular seem to have taken over other organisations, such as parts of the UN for example. Corruption is endemic to the human condition however. Regarding the region (mostly Africa) – there is a fine line between helping ones friends and families and corruption, in some cultural contexts this line is not where we expect. It is imperialism to impose our values on others like this when we have so much ‘acceptable’ corruption in our own private and public sector. We should get our own house in order (for me, the UK) before we judge others.”

Elsewhere in this blog [book] I comment on Easterly’s overall critique well summed up by this veteran aid worker. Painting with a brush so broad is always dangerous, though, and may short-circuit more detailed discussions.

Pot calling the kettle black

Here are several comments pointing out that corruption is a fact everywhere and that to narrowly focus on corruption in the developing world is classic Western-centrism.

“Corruption is a problem everywhere. Worst corruption and influence peddaling is in my home country, the US. It bothers me that people complain so much about corruption in the developing world when it is literally magnitudes greater in the US political system.”

“Four out of the last seven governors of Illinois have been charged with crimes related to corruption. It is a constant presence in all fields, aid work and otherwise.”

a constant presence in all fields, aid work and otherwise.”

“Corruption exists everywhere -and the biggest $ corruption over the years has been in the ‘first world’ banking/investment sectors. It is perhaps more obvious day-to-day in other places – but exists everywhere.”

As a sociologist and as a US citizen I must say that I agree with these assertions. Cockroaches scatter in the light, and to the extent that the spotlight on corruption tends to point outward and not inward, corruption in the West will remain a mostly hidden, metastasizing cancer.

The impact of corruption on organizations, beneficiaries and on the aid workers

That corruption is a negative force seemed to be a common, obvious theme, and some respondent’s were quite forceful about this point.

- “Corruption is the biggest cause of poverty. If you are in aid, you deal with corruption.”

- “Non-internationally recognized government – corruption is everywhere all the time from the shopkeepers and the drivers to the vice president. It is expected.”

- “The government is corrupt, the UN is corrupt, really the whole system is inherently corrupt.”

The human resources and time that are devoted to dealing with corruption can in some -most?- cases drain from efforts to realize the central mission of an aid or development organization. This respondent put it this way:

“Although I have not witnessed any corruption in my organisation, the paranoia about corruption affects us all negatively because it is the primary reason for the monumental bureaucracy, box ticking, accountability and reporting requirements, which take up 90% of our time, pulling us away from our real work. It is also the reason why our procurement and recruitment processes are so complex and take forever.”

Indeed, if we could all be and act with integrity the world would be a better place. This comment does lead to a good question, though, namely how much overhead -broadly defined- is invested in dealing with corruption within the humanitarian aid sector?

This next respondent summarizes one likely common systemic issue and sheds even more light on how aid and development initiatives contribute to corruption.

“As I have gained experience in and knowledge of the institutional environments of many different countries, regions and cultures, I have come to understand how deeply corrupting the influence of developed-world institutional actors can become when local authorities and political insiders manipulate the characteristics of engineering-related aid projects to feed the existing hierarchy of endemic corruption within a particular locale, and the aid institutions simply don’t have the time or the longer-term awareness to place a higher priority on preventing or avoiding that sort of cooption because of their own internal deadlines and personnel advancement objectives.”

A second question, perhaps as important, is what psychological toll does dealing with the complex moral, ethical and personal issues related to corruption (in all forms) days after day take on aid workers? To what extent does this lead to burnout, loss of idealism, and painful soul-searching? How many aid workers have been in situations where making the call to refuse to give a bribe cost necessary succor or even lives in the short run? Every situation is unique, and the “right choice” will always be a judgement call on some level. Living with that burden can be onerous at best, mentally destabilizing at worst.

Concluding thoughts

I began this post with some thoughts about how to define corruption. As I read through all 313 narrative responses to our question I learned to appreciate more and more the gift I was being given by all of those who responded to the survey. The aid worker voices concerning corruption were thought provoking, to say the least.

At the end of the day I will support the argument that there is much to consider when considering this concept of corruption. I am reminded of a comment by Antonio Donini, namely that “Humanitarianism started off as a powerful discourse; now it is a discourse of power, both at the international and at the community level.” I think part of the power the West wields is the power to drive the narrative in a self-serving manner and, in the case of corruption, perhaps not looking in the mirror long enough. I also think that this is a conversation worth having often, in depth, with passion and with concrete out-come oriented action as its goal. The topic of corruption raises many issues that for many aid workers are fact of life on a daily basis. The responses to our open ended survey question, a small sample of which you read above, were all over the board, some people responding with confusion, some snarky, but there were many that were well thought out indicating that at least for this question our survey served to generate a cathartic or at least reflective moment where frustrations could be vented.

So, cancer of corruption or the culture of corruption? Yes.

As always, please contact me with questions or comments or to add your thoughts for discussion.

Follow

Follow