The mental health of Jordanian humanitarian workers

More results from the Jordanian humanitarian worker survey.

Suicide happens

I write this post in the immediate aftermath of watching the many tributes to American author, chef, and CNN ‘correspondent’ Anthony Bourdain. News of Bourdain’s suicide came just days after designer Kate Spade met the same fate. As is the way of the news cycle, there is now a great deal of attention on mental health issues generally and depression specifically.

This topic is personal. Regarding depression, I can say ‘me too.’ It sucks.

Given the context, this post on the mental health of humanitarian aid workers seems timely. As a blanket statement I’ll argue (the obvious?) that far too little attention is paid to the mental health of both aid workers and those in the affected community.

Given the context, this post on the mental health of humanitarian aid workers seems timely. As a blanket statement I’ll argue (the obvious?) that far too little attention is paid to the mental health of both aid workers and those in the affected community.

Yes, I know delivery of effective treatment is complicated and even contentious, and many HR departments do address this issue, but we continue to live in a world where denying stress, burnout, depression, and the wide array of symptoms of mental illness is far too common.

Change will come, and more voices being heard is a step in a positive direction. It is to all of the Jordanian humanitarian workers that suffer from emotional stress now in their daily work lives that I dedicate this post. May we all be heard.

Jordanians feel stress

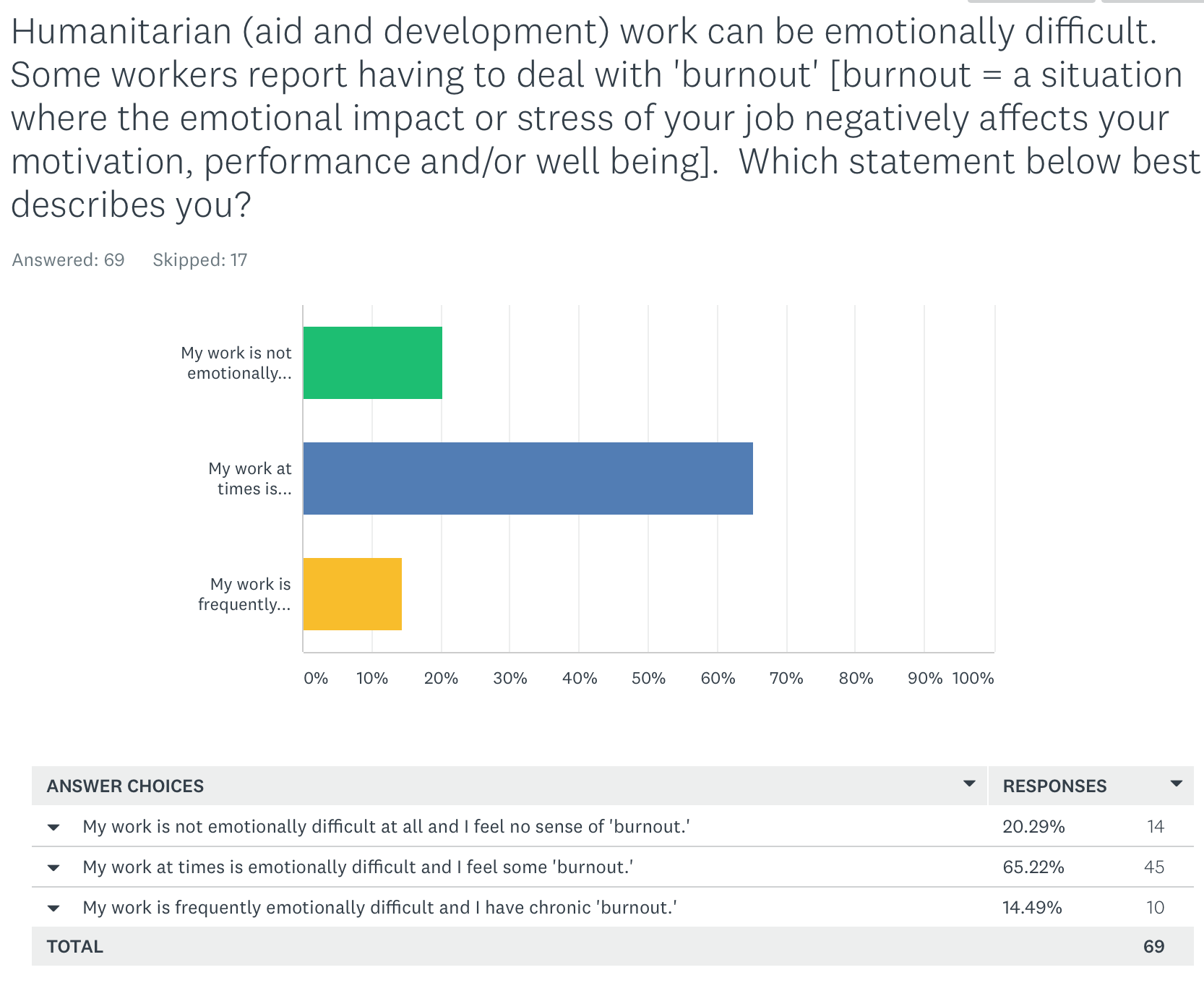

As I workshopped drafts of survey questions with several Jordanians I found that the term ‘burnout’ was unevenly understood. The question wording we settled on was “Humanitarian (aid and development) work can be emotionally difficult. Some workers report having to deal with ‘burnout’ [burnout = a situation where the emotional impact or stress of your job negatively affects your motivation, performance and/or well being]. Which statement below best describes you?”

The aggregate data are fairly clear, with the vast majority of the respondents -80%- reporting that their work is emotionally difficult and they have ‘some’ or ‘chronic’ burn out. One female commented,

out. One female commented,

“This line of work is very demanding, long hours, weekends, very little support, fatigue, it effects the physical as well as mental health.”

Another made an interesting distinction, remarking that,

“My job is extremely emotionally difficult, but I cannot identify myself having chronic burnout.”

A gender difference in the data exists, and males -by a ratio of two to one, 22% to 11%- were more likely to say that “my work is emotionally difficult and I have chronic ‘burnout.”

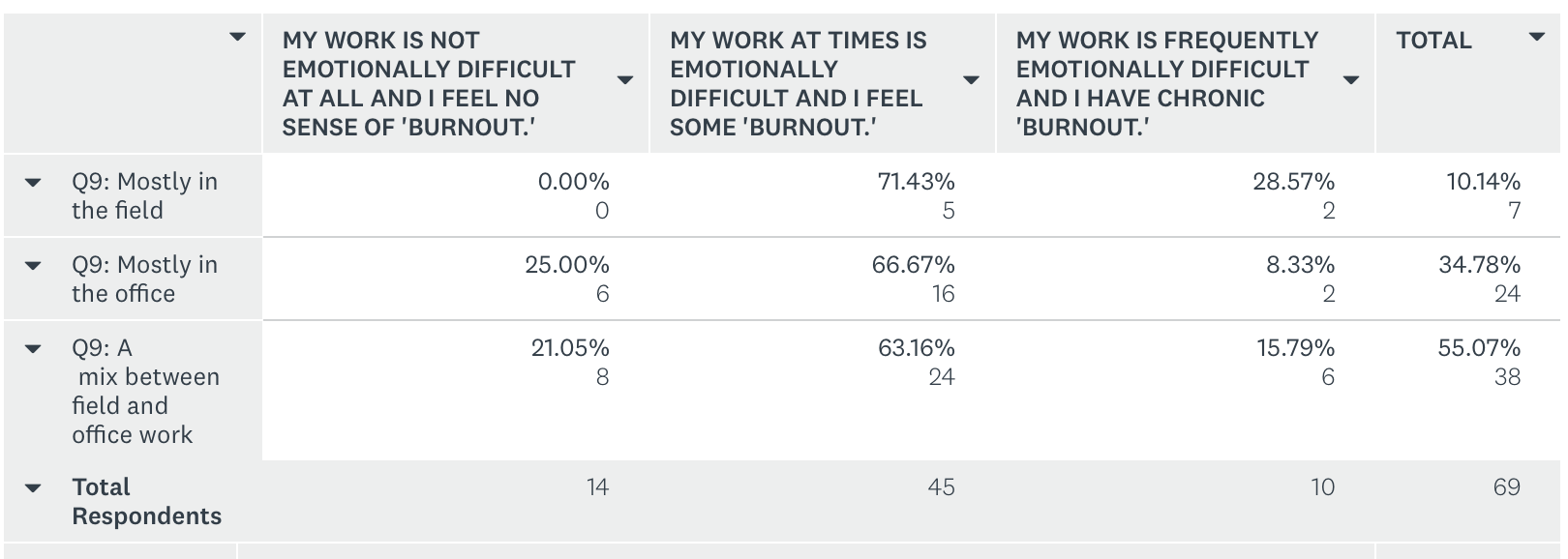

Probing into the data more deeply, I found that among those who described themselves as working primarily in  the field none -0%- said “My work is not emotionally difficult and I feel no sense of burnout.” as compared a quarter -25%- of those who work ‘mostly in the office.’ Those who work in the field were over three times as likely to say indicate that “My work is frequently emotionally difficult and I have chronic burnout.” That increased proximity to the affected community is associated with higher emotional stress seems clear -and predictable.

the field none -0%- said “My work is not emotionally difficult and I feel no sense of burnout.” as compared a quarter -25%- of those who work ‘mostly in the office.’ Those who work in the field were over three times as likely to say indicate that “My work is frequently emotionally difficult and I have chronic burnout.” That increased proximity to the affected community is associated with higher emotional stress seems clear -and predictable.

As exploratory research, the overall goal of this survey was to add nuance to our understanding of the issues and to raise new, or at least more precise, research questions. To wit, why does it appear that males are more likely to claim their work causes burnout, and in what ways does working in the field’ generate more of an emotional burden?

A comparison

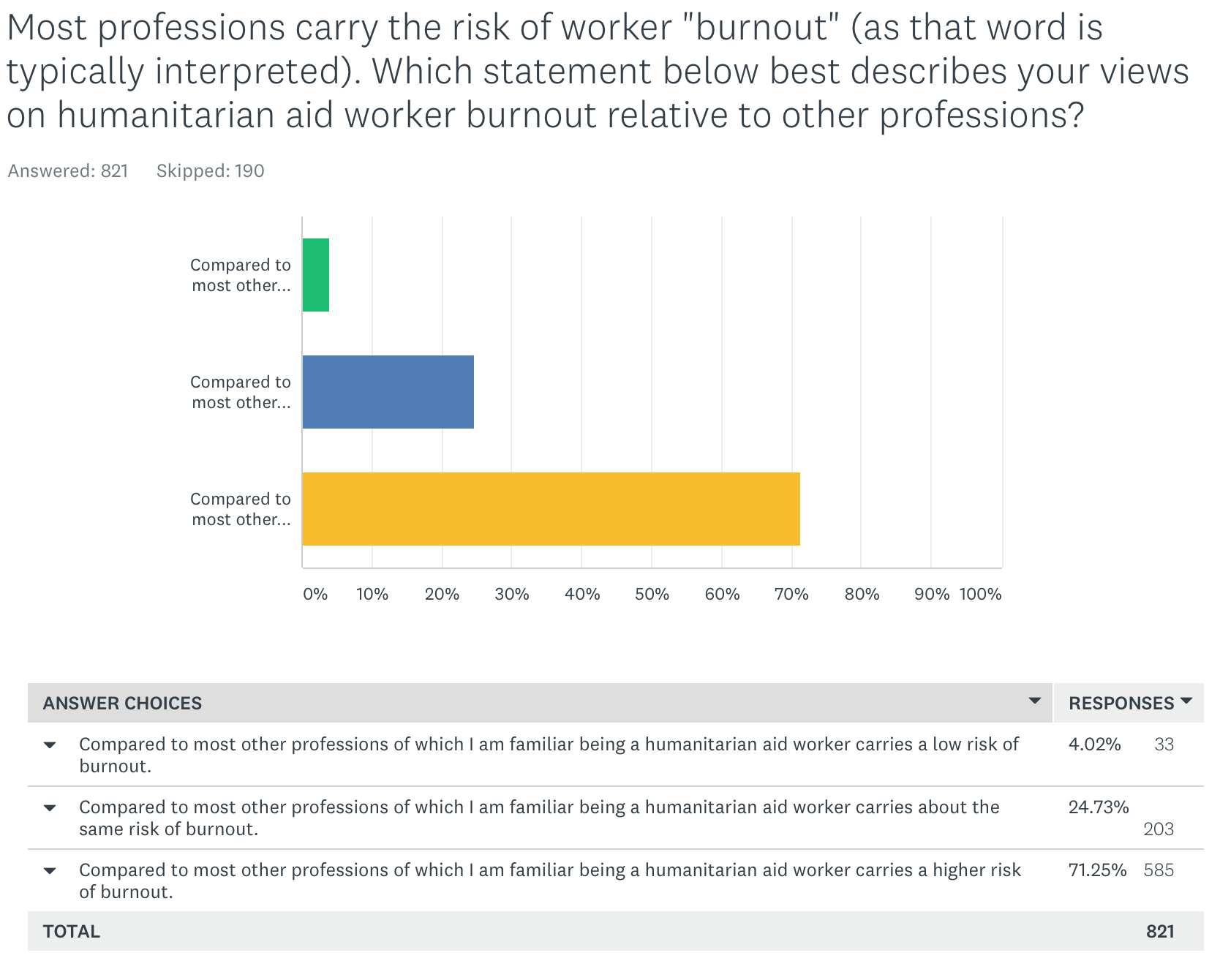

The survey of international aid workers I did in 2014 had a similar question. “Most professions carry the risk of worker “burnout” (as that word is typically interpreted). Which statement below best describes your views on humanitarian aid worker burnout relative to other professions?” The results  then compliment the Jordanian data, and affirm other research on this topic. A large majority of those surveyed – 71%- agreed that “Compared to most other professions of which I am familiar being a humanitarian aid workers carries a higher risk of burnout.”

then compliment the Jordanian data, and affirm other research on this topic. A large majority of those surveyed – 71%- agreed that “Compared to most other professions of which I am familiar being a humanitarian aid workers carries a higher risk of burnout.”

The ‘helping’ professions in general can be high risk in terms of mental health, and being a humanitarian worker -dealing with geopolitical and environmental catastrophes- is inherently difficult to deal with emotionally for all but the rare few who are able to effectively wall off work activities from their emotions. Perhaps Alessandra Pigni’s The Idealist’s Survival Kit. 75 Simple Ways to Avoid Burnout

may be of use to many, even -or especially- for those working in the Levant.

Please contact me with comments or questions via email.

You can access all of my posts related to Jordanian humanitarian workers here.

Follow

Follow