“In terms of dealing with the tension between the humanitarian bureaucracy and the humanitarian mission, I think working on this project is the only thing that could have kept me in this field.”

-Lillie Anne, speaking from Amman about her work on the The Mahali Lab

Serendipity

Social media certainly has its downsides, but one major positive function of the Facebook platform is that groups can be formed, bringing together people that otherwise would remain proverbial ‘ships passing in the night.’ Many months ago I joined the closed Facebook group Fifty Shades of Aid, and scrolling through the posts has allowed me to deepen my understanding of aid workers around the world.

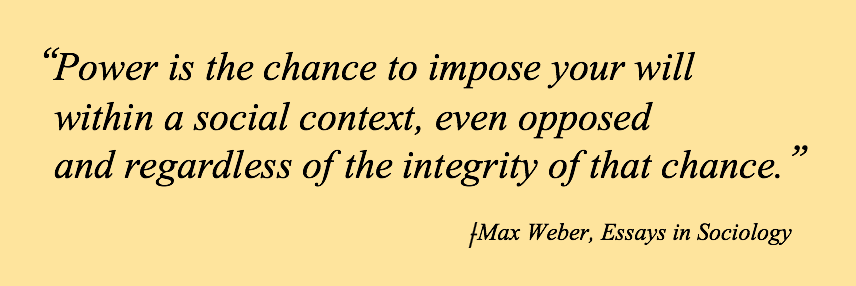

Researching and writing about humanitarian aid workers is part of my job as a professor of sociology, but a bigger part is teaching and mentoring undergraduates. This fall I am teaching our department’s required ‘classical sociological theory’ course and, as luck would have it, as I was covering the German sociologist Max Weber I happened up this poem in Fifty Shades:

Reading this poem I was struck by how clearly Lillie had captured a concept I had just discussed with my students, namely Weber’s ‘iron cage of rationality.’ Her use of phrases to paint a picture of frustration, of being caught between the ‘humanitarian bureaucracy and the humanitarian mission’ are masterful, and I immediately knew that this was something that I wanted to share with my students to amplify their understanding of Weber’s ‘iron cage.’

‘Our M&E tools grate against compassion’

I began a conversation with Lillie and found that she is working in Jordan with Syrian refugees. That my current research is on Jordanian aid workers and issues related to work in that sector made our chance meeting all the more fortuitous.

Over Skype I asked her about her life as an aid worker, her thoughts on my research on local aid workers in Jordan, and the poem that brought us into contact. I wanted to know more about how she both experiences and understands the clash between the urge to maintain dignity for all and the need to ‘get the job done efficiently according to protocol.’

A Jersey girl working in Jordan

Getting to know each other at the beginning of the interview, I learned that Lillie is from New Jersey, which in her words is “well-known for its culture and international focus.” Lillie allowed me to talk about my research -giving me very useful feedback on a draft of the survey intended for local aid workers in Jordan- and we talked about many topics before I finally asked her to explain the background behind the writing of her poem.

She explained,

“… I had just transitioned to the position I’m in now a few weeks before, and I had been before that in a cash and livelihoods program. We had just revamped our coping strategies index and our vulnerability assessment that we were using to determine if people were eligible or not for cash assistance.

You do have the sense when you’re looking at the questions -and there’s a standard one used for that in Jordan- that this is degrading. This survey is dehumanizing, asking people specifically about the food groups that they’re eating, and how many people are disabled? How many people can’t work? It’s rudimentary. It’s a process-oriented thing when you’re conducting this survey, and you can be doing hundreds of them in a day.

I had just gone from that work to this community-driven innovation lab, which involved very long, unstructured conversations with humans, just to build connections, build trust, and get to know people, and it was that juxtaposition that gave birth to that poem.”

I asked Lillie to explain what the poem was about just as she would if she were talking to my students. Her explanation adds a new and powerful dimension to what I had given my students, and is a spot-on capturing of what I think Weber, a man who understood power, would say. She noted that,

“I think really at the heart it’s about power and reflecting on the power that we have when we’re in this position, deciding if someone can meet their basic needs or not, if they have a livelihood or they don’t, or they have this opportunity or not, and that I don’t think we reflect enough on how enormous that power is in this humanitarian sector, and how people feel interacting with us, interacting with our services. How do we make them feel? It’s that bureaucratic influence, that people are a means to an end to implement your program or achieve certain outcomes or certain indicators. We just rarely reflect on human experience for the person who’s interacting with us.”

“I think really at the heart it’s about power and reflecting on the power that we have when we’re in this position, deciding if someone can meet their basic needs or not, if they have a livelihood or they don’t, or they have this opportunity or not, and that I don’t think we reflect enough on how enormous that power is in this humanitarian sector, and how people feel interacting with us, interacting with our services. How do we make them feel? It’s that bureaucratic influence, that people are a means to an end to implement your program or achieve certain outcomes or certain indicators. We just rarely reflect on human experience for the person who’s interacting with us.”

When explaining Weber’s iron cage I steal some phrasing from Blaise Pascal (“And thus, not being able to make what is just, strong, one made what is strong, just.”). I point out that, increasingly in an age of inexorable, unavoidable, and pervasive bureaucratization, with increasing frequency we are faced with the fact that not being able make that which is real measurable, we tend to make that which is measurable real. It is rational to move forward with a necessary process that allows for an accountable and efficient allocation of scare resources, but that act of rationality crushes out the humanity of the social interaction.

“Pluck this pain from midair and brutalize it with an algorithm/Your identity databased and replaced with heart-scraping simplicity”, indeed. The words of an artist.

A universally felt frustration

As evidenced by the scores of reactions and comments to her poem on Facebook, it is obvious that the clash between the humanitarian bureaucracy and the humanitarian mission Lillie speaks of is a universally felt frustration within the sector.

What I heard Lillie say, in so many words, was that at some points her job made her a participant in an almost inherently dehumanizing process. She was undercutting dignity by going straight to some very personal questions, or what could appear to be personal questions. She agreed and said,

“Absolutely, and this is the thing that just kept coming back from these community consultations that we’ve just done is that people do feel like they’re completely compromising their dignity when they’re interacting with humanitarian services, and it came back from everyone we talked to in every city, male, female, youth, older people, so many different stories that people told us just to try to show us, this is what we experience and feel when we come to you for help.”

In his book That the World May Know: Bearing Witness to Atrocity (2007) James Dawes puts it this way, “This contradiction between our impulse to heed trauma’s cry for representation and our instinct to protect it from representation -from invasive staring, simplification, dissection- is a split at the heart of human rights advocacy.” (emphasis in original)

That the word ‘dignity’ is used in the very first sentence of the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is significant and lies at the heart of the work Lillie and others are currently doing in the Mahali Lab. This work, an effort to soften the bars of the ‘iron cage’, is important and, I hope, will continue to inspire more poems that bear witness to our human struggles.

My deepest thanks to LillieAnne for taking the time to help me with my research and explaining in such powerful detail the story behind her poem. More of Lillie’s poetry can be found on her blog Torn to Canvas: Writings from a restless mind.

I have written a good bit in other posts about the bureaucracy in the humanitarian sector and about the sector as a whole. You can find my book-length compilation of aid worker voices and comment about the sector here.

As always, you can reach me here if you have comment, critique, or commentary.

Follow

Follow