The future of aid is the end of it: the bigger picture of aid localisation

Insights by Arbie Baguios

The World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016 called for aid localisation. Although by how this phrase is often used one would think aid is yet to be ‘localised,’ when in fact, according to ALNAP’s State of the Humanitarian System report in 2015, 80% of the 4,278 registered NGOs worldwide are national organisations, and 87% of the 249,000 aid workers are local or national staff.

What the summit actually called for was to increase the share that local humanitarian actors receive out of the global aid budget. Despite local actors being the fastest and most effective aid providers, the Global Humanitarian Assistance report found that in 2016 they directly received a meagre 0.3% out of the USD 27.3bn global spend on aid.

Aid is already ‘localised’ – power within the aid sector is not.

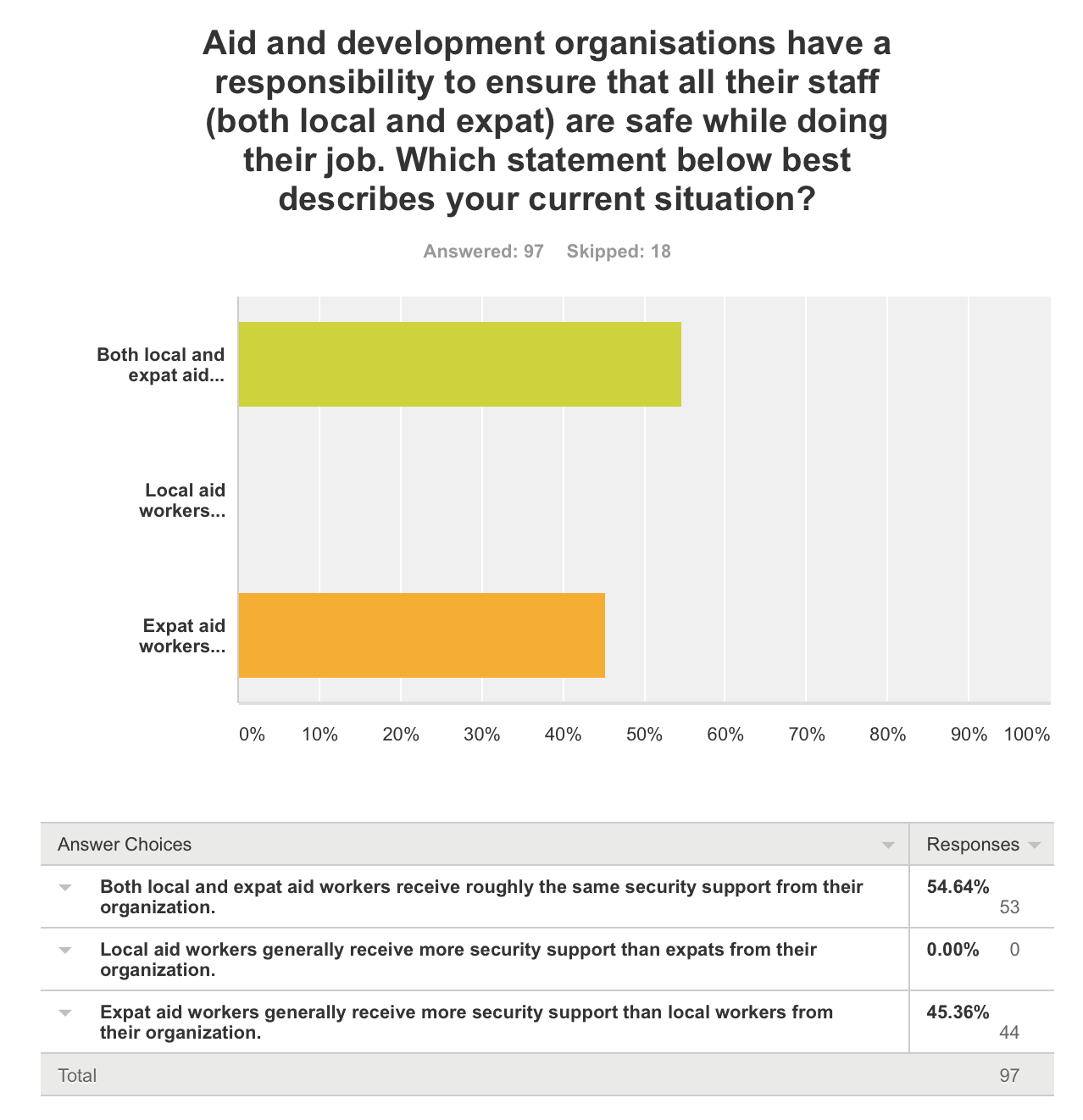

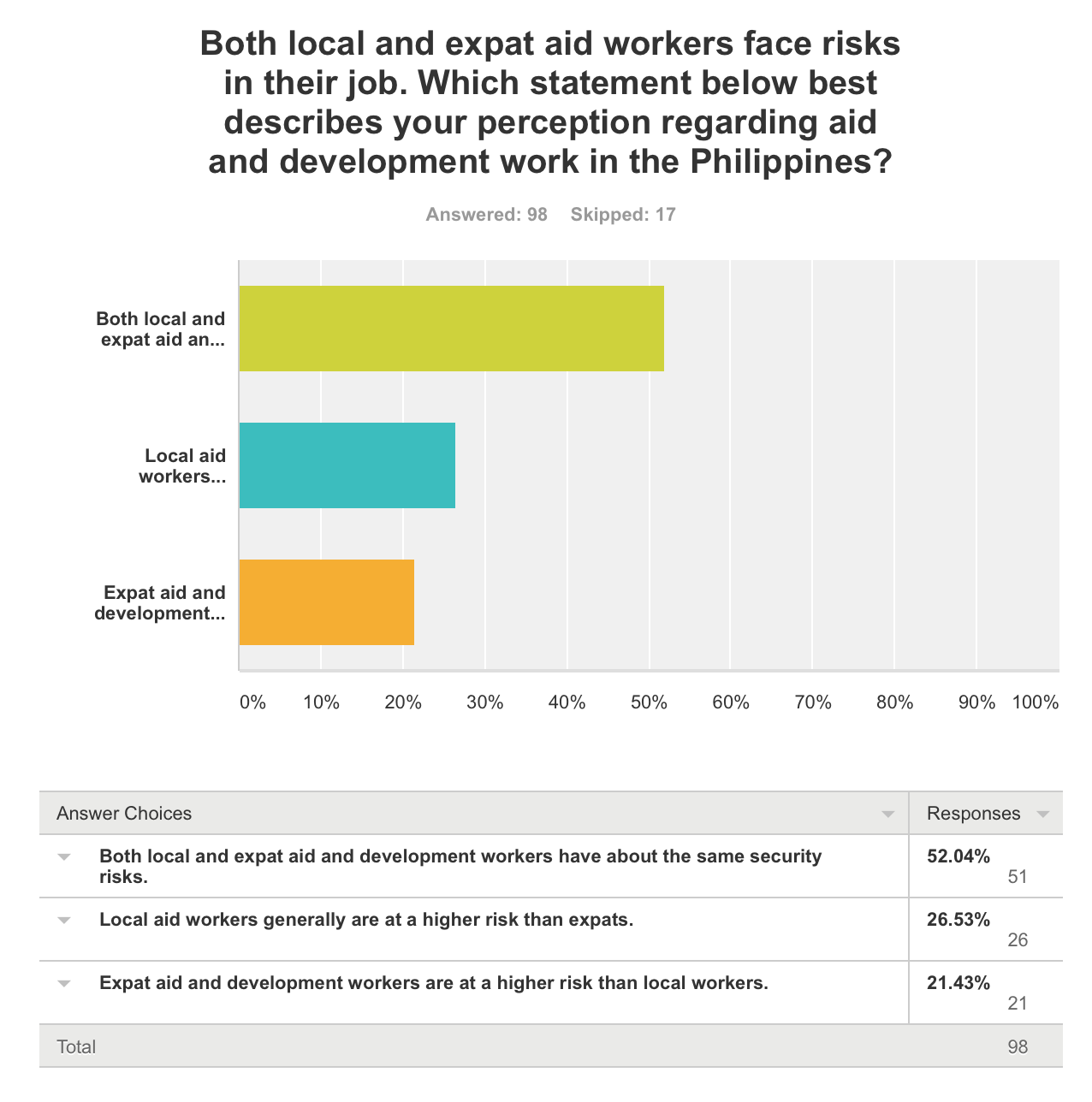

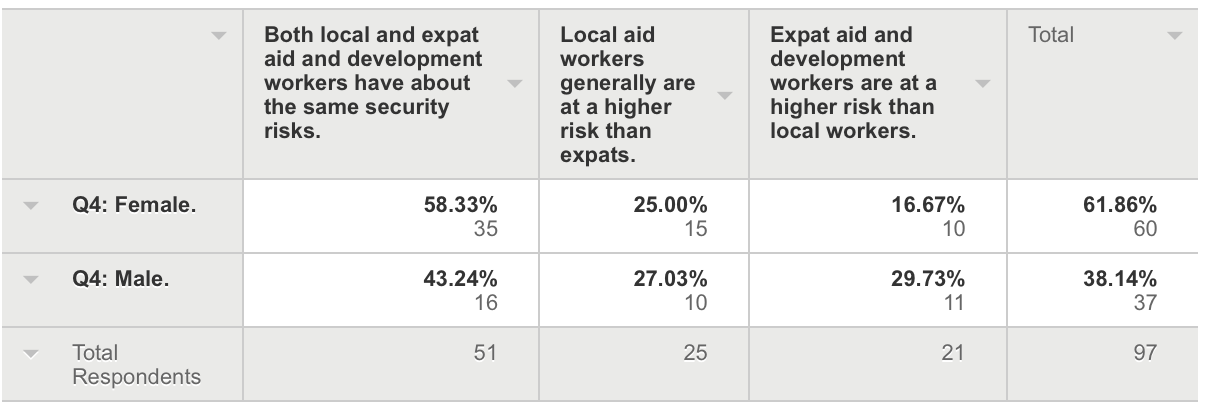

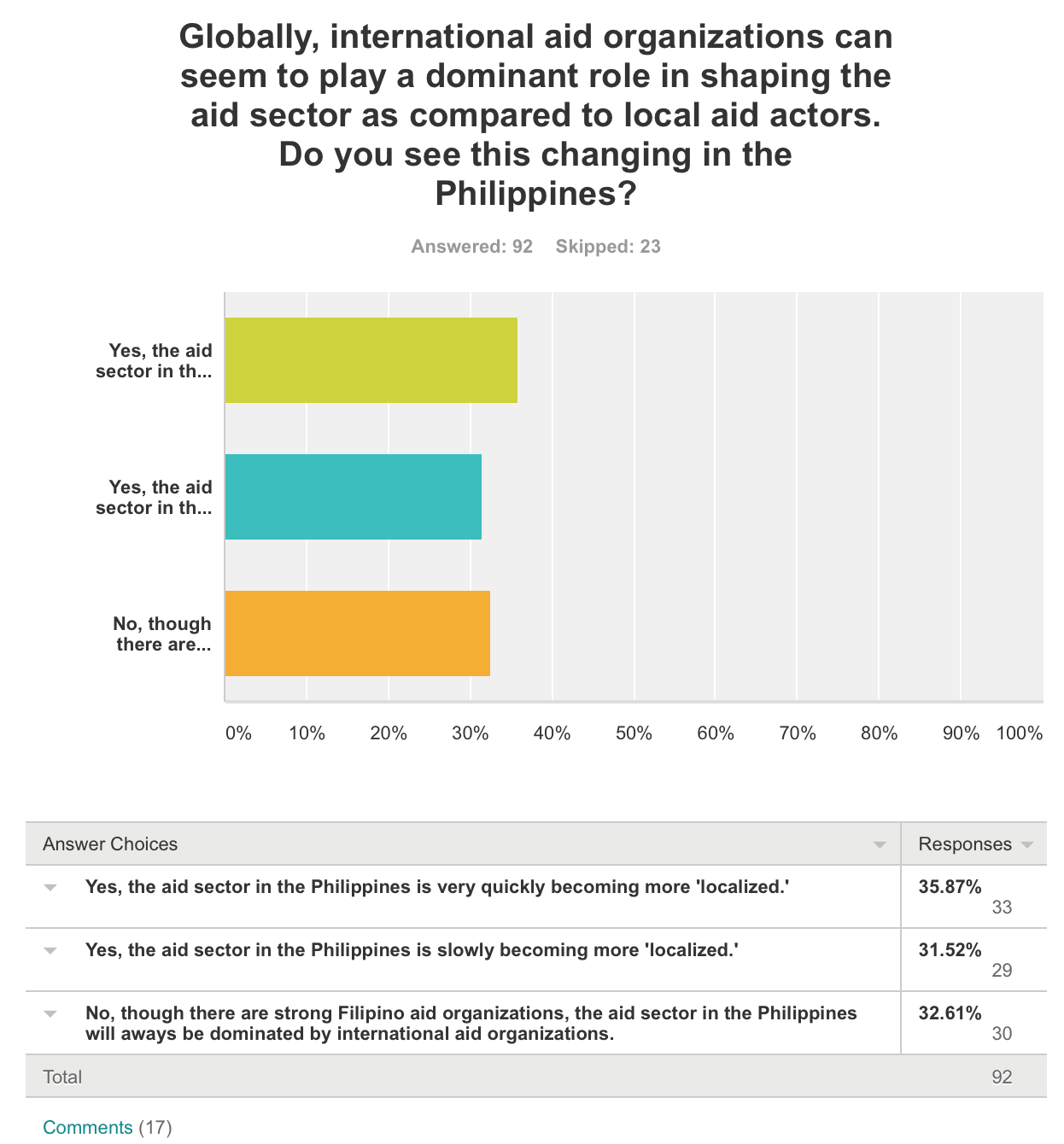

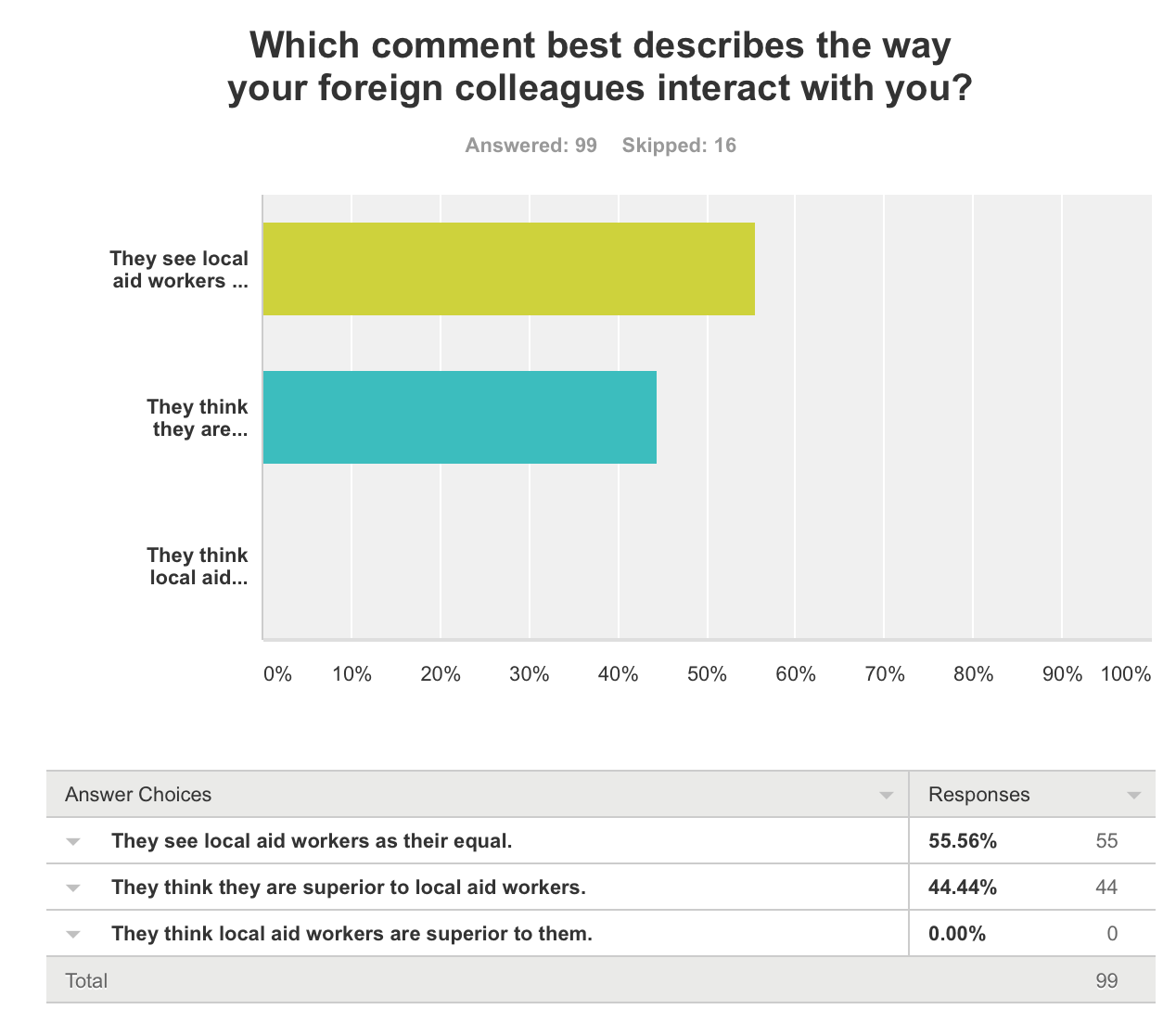

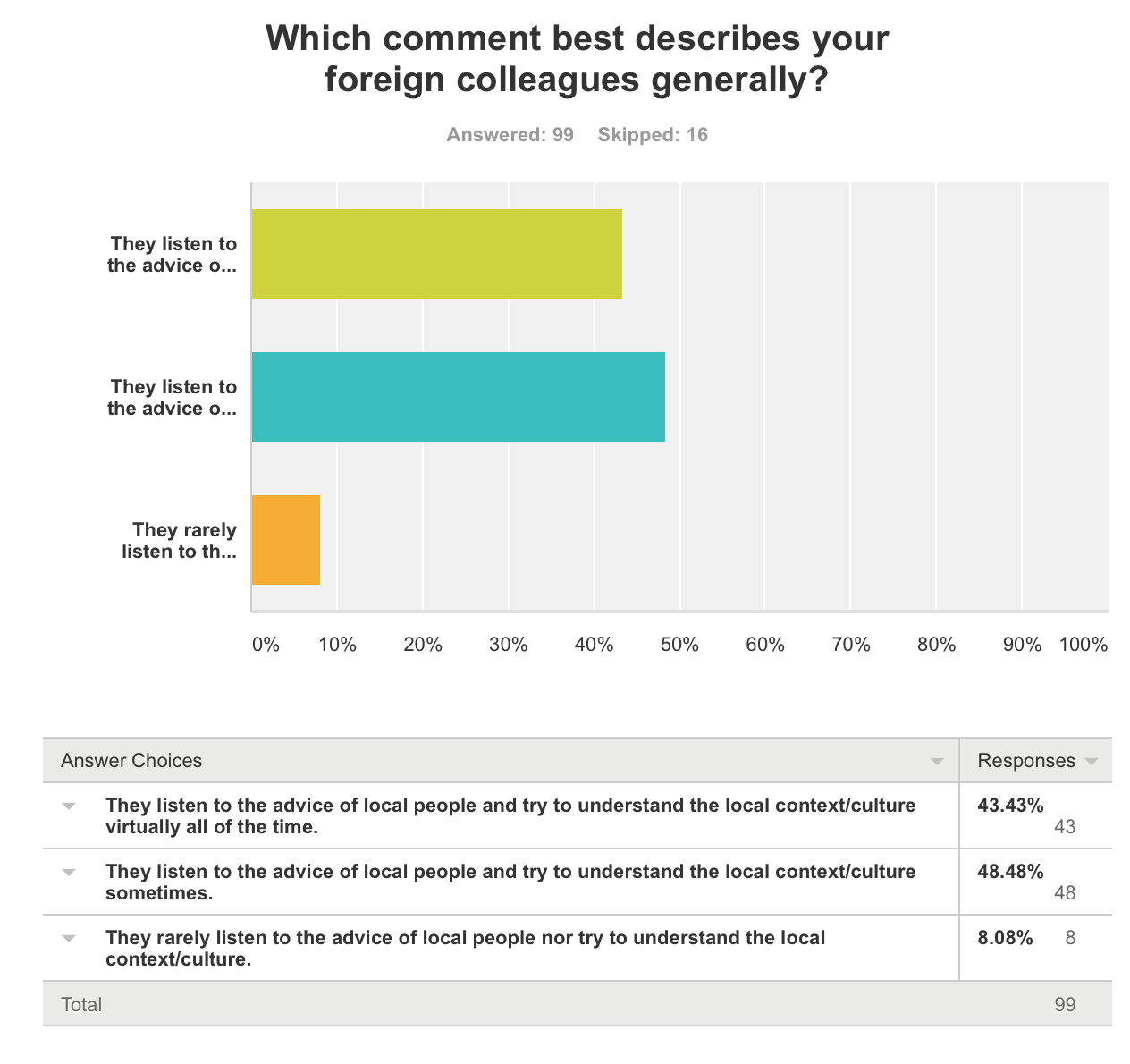

Over the past few months, my colleague and I surveyed local aid workers from the Philippines to get their views on a range of issues including localisation. Responses on this particular question were evenly split: 33% thought aid work in the Philippines was quickly becoming localised, while 30% did not. One comment read: “While staff composition is becoming localized, key power holders are still expats and decision making is still with global HQs.”

Most other comments on that question rightly pointed out the issue about funding (e.g., “[B]ecause of the funding mechanism and availability, international organizations would still dominate…”). But true localisation of aid – that is, the localisation of power within the aid industry – is more than just about who gets the money (although it is a significant part of it). Sometimes it’s also about who gets the job.

All aid workers lives’ matter?

There are a number of issues on and around ‘aid workers’ – not least of which are the ‘local staff vs expat staff’ and ‘Global South aid worker vs Global North aid worker’ debacles.

These have been exhaustively debated in many places, especially online and including on our blog. When these get brought up on the Internet, I notice a predictable reaction: people get defensive. The next time this gets talked about on Facebook or Twitter, play bingo: spot that one guy who always use the most extreme example like Afghanistan or South Sudan; or the aid worker equivalent of, “My best friend is from the Global South!”; and even the outright dismissal of the problem as an insignificant cliché or a non-existent myth.

In our work, when a community member registers a complaint against our programmes, we are compelled to resolve the issue – regardless if it’s real or perceived. If someone said they feel a form of injustice because they were not included in the beneficiary list, a capable BenComms officer would handle this by explaining the beneficiary selection process and then telling them how the programme is helping their neighbourhood, too. We cannot say the injustice they feel is simply not true; instead, we listen, acknowledge, and address.

In the same way, until the ‘local vs expat’/’North vs South’ problem is systemically addressed within the aid sector, there will always be tweets and blogs and Fifty Shades of Aid posts that highlight and criticize the inequalities and injustices (real or perceived) between the two.

It’s time the aid sector acknowledges and addresses the elephant in the expat lounge. We can begin by asking questions and getting the facts.

Perhaps NGOs could publish the statistics on their staff: how many are locals vs expats? Of the expats, how many are from the Global North and how many are from the Global South? If one group is disproportionately (under)represented, why? Between locals and expats, what is the average pay difference and how is their pay calculated? What is the system or criteria used when a role is advertised as expat or local? What development opportunities do they provide to local staff who wish to move on to expat roles?

Maybe we could ask international NGOs headquartered in London or Washington or Brussels: what are they doing about the fact that they are an international NGO but are unable to get visas for international staff, particularly from the Global South? Have they tried to collectively negotiate with the home affairs ministries of their governments? We opine how it is increasingly difficult for expats to get visas in countries like South Sudan or Kenya (and in fact we form government advocacy groups to address this), but accept by default that, outside of the UN, it is virtually impossible to employ non-nationals in the UK, US or EU.

Until we have these data and facts which will enable us as a sector to come to an informed analysis on the issue – in short, until we finally systematically address it – I’m afraid most discussions will only be inundated by anecdotal evidence about how one time in Maiduguri this guesthouse was full of Kenyan expats.

But I’d like to believe the aid localisation agenda means something so much more than this. Beyond being about funding or staff, aid localisation is ultimately about the future of our societies.

A world vision?

In the aftermath of the Grenfell Fire tragedy in London, I volunteered at the designated assistance centre. The programme to support those affected by the tragedy is similar to many international humanitarian operations: the government has taken the lead and coordinates with civil society organisations to provide cash, food and NFIs, and medical and psychosocial support.

In the Global North, most small- to medium-scale emergency responses resemble international humanitarian work (such as cash transfers for fire victims in Canada or NFI distributions after floods in England) sans INGOs flying in and expats getting deployed. And ‘development’ issues like poverty, employment, education or infrastructure are sorted out by their national government, never UN agencies.

At a talk at the LSE, Dr Jim Yong Kim, President of the World Bank Group, introduced the concept of ‘global convergence of aspiration.’ Through technologies like the Internet, someone from somewhere poor can learn to want the same things from somewhere rich. Think of a rural teenager wanting to enjoy the same nightlife he sees on Facebook from his cousin from the city; or a girl from Southeast Asia desiring to go to that same prestigious university in London her favourite YouTube star went to.

This ‘convergence of aspiration’ can be experienced not just on an individual level but on a societal level, too. Just ask any Filipino standing in line for hours for the train what kind of public transportation system they’d want to see in their country. I bet their answer would be somewhere along the lines of, “Just like America’s!” or “Just like Singapore’s!”

As a Filipino aid worker based in an HQ in London, I feel this way about my country’s humanitarian and development sector. I’m sure I speak on behalf of many Filipino aid workers when I say that my vision is for my own country to be able to address its development issues on its own and respond to its emergencies without requiring international assistance.

Respondents of our survey are under no illusion about the current capacity of Philippine society: “The aid sector proliferates [here] because our own government consistently fails to address the many problems that beset our country,” reads one comment. But they look on to a singular horizon: “The Philippines should also begin to take on most of the leadership roles in development as a middle income country,” states another.

Beyond how INGOs trickle down the funding to their local partners, or whether the expats they employ are from the Global South, I’d like to think that, ultimately, this is what’s at the heart of aid localisation: a reasonable aspiration for countries to have the capacity and resources to solve most of their own problems.

The end of aid?

This concept isn’t new. Not so long ago the phrase du jour for aid workers was to “work our way out of a job.” But this idealistic vision for the future has somehow faded in favour of trying to fix a ‘broken system.’ By its nature, however, a ‘system’ is adaptive (a favourite aid jargon!) and aims to preserve itself.

A report called “The Future of Aid: INGOs in 2030” published in July 2017 by the Inter-Agency Regional Analysts Network (IARAN) states that international organisations are at risk of irrelevancy due to, among other things, the rise of local and national aid actors. The Guardian, referencing the report, wrote that aid charities must “change or die.”

I wonder, though: shouldn’t we just, well, let it die?

The report says: “With the growth of national NGOs and the creation of South-South alliances, national NGOs will grow in scale and importance and occupy more of the humanitarian space. The power balance between NGOs and INGOs will shift.” If this is so, why swim against the tide? Shouldn’t the call to action, then, be to ensure that current global attempts to ‘reshape aid’ truly disrupt the status quo and head towards the South’s greater independence from international assistance?

Final thoughts

To be clear: I believe in aid. I believe that as long as poverty or crises ‘somewhere else’ are broadcast to the world, there will always be a need for an international system that can effectively manage the inevitable outpour of public philanthropy. I believe that humanitarian assistance will remain necessary in particular contexts, such as in conflicts or overwhelming large-scale sudden onset disasters.

This transfer of resource is always welcome. But I hope we continue to see the transfer of power, too. I hope to see an aid sector where the most affected people, and the institutions within their own society, are the ones who get to decide and implement the solutions to their own problems. (And, perhaps most importantly, I hope that these solutions lead to such a point where future problems are minimised and more locally manageable.)

The aid localisation agenda is, as we often fondly say in this sector, complex. Nations’ and communities’ self-sufficiency is inextricably bound to wider social, economic and political realities far outside the remit of our sector. Although if we are to drive localisation’s momentum forward, the self-preserving aid system must be shaken up; and the business-as-usual way of working between donors, INGOs, Global South actors, and local communities needs to be rethought.

As we carry on with our industrial churn of budgets, logframes, gantt charts, and other minutiae of the business of aid, we should try to remember once in a while, and no matter how hazy, the bigger picture of aid localisation: one where all nations and communities – local people – are able to solve their own problems.

Follow

Follow

uestions than we have answered. More work needs to be done. More comment and analysis soon.

uestions than we have answered. More work needs to be done. More comment and analysis soon.

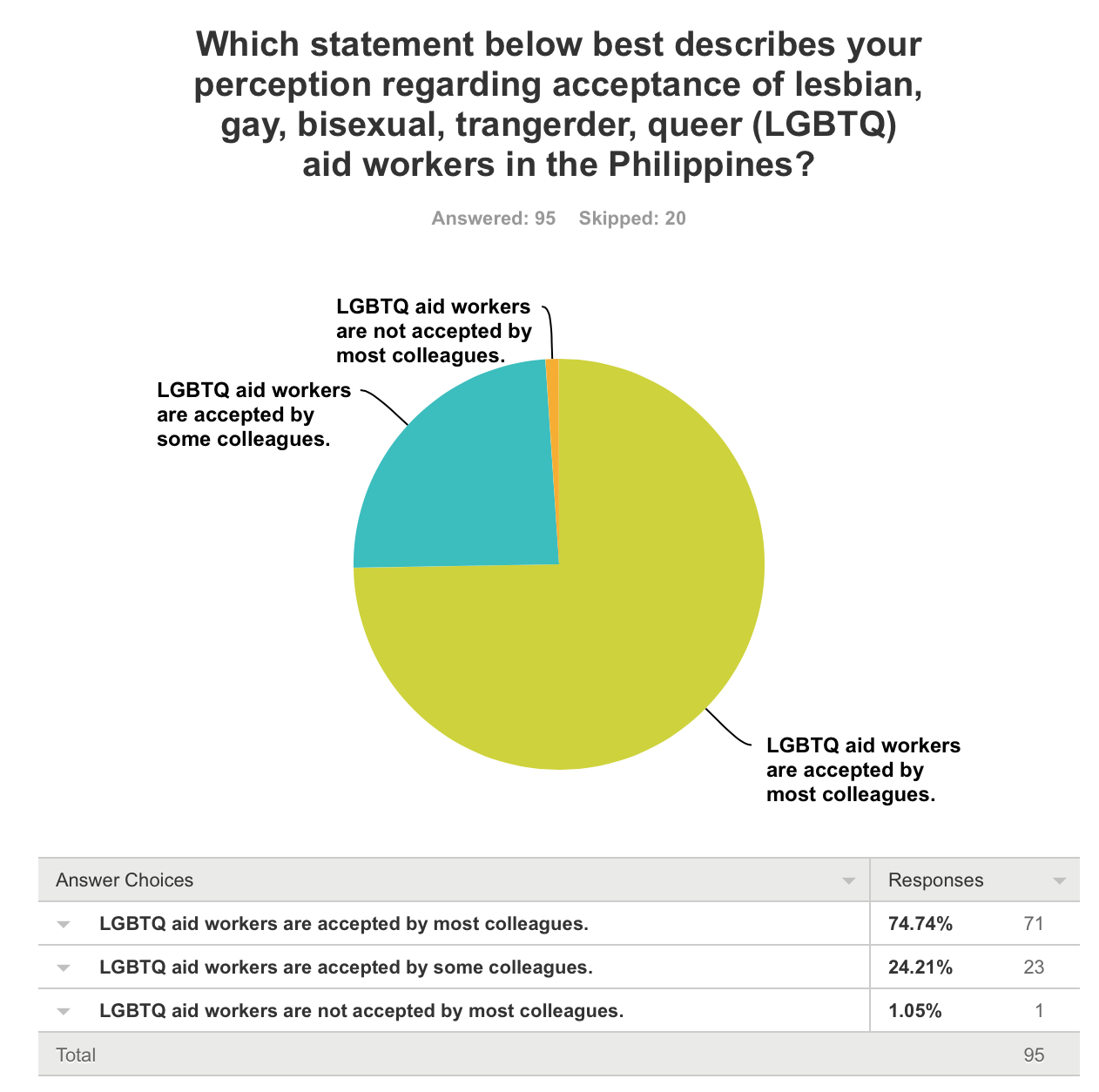

, with 75% reporting that, “LGBTQ aid workers are accepted by most colleagues.” That a significant proportion of those responding -25%- signaling that LGTBQ colleagues are accepted only by some or no colleagues is troubling and to me indicates that more focused research should be done on this topic.

, with 75% reporting that, “LGBTQ aid workers are accepted by most colleagues.” That a significant proportion of those responding -25%- signaling that LGTBQ colleagues are accepted only by some or no colleagues is troubling and to me indicates that more focused research should be done on this topic.