“Many of my colleagues are non-Jordanians. We get a long very well and respect each other. However, in general, the international humnaitarian/development sector places ‘expats’ at the top of the top of the power heirarchy and values their knowledge most, harkening back to colonial times I find. Jordanian women are often least valued in the sector. It’s a very much neo-liberal sector that discourages fighting back and speaking up especially on the part of ‘national staff.'”

-female Jordanian aid worker

Jordanian voices on relationship between ‘international’ and ‘national’ staff, Part I

‘Localization’ within the sector

Long before the WHS “Grand Bargain” in 2016 and in the years since there has been much conversation about ‘localization’ within the sector. Any real change in how the sector operates necessarily involves shifts in the loci of power and, at the personnel level, changes to the relationships between ‘international’ and ‘local’ staff.

I appreciate and understand the implicit and significant oversimplification  embedded in the cliche ‘expat’ versus ‘local’ binary. That said, as with all cliches, there are elements of truth which bear examination. The ‘expat’ versus ‘local’ reality exists as a social fact in the lives of many within the sector, and most certainly in Jordan.

embedded in the cliche ‘expat’ versus ‘local’ binary. That said, as with all cliches, there are elements of truth which bear examination. The ‘expat’ versus ‘local’ reality exists as a social fact in the lives of many within the sector, and most certainly in Jordan.

With all that in mind, I report below on the first two of five questions on my survey addressing the relationship between ‘international’ and ‘national’ staff in Jordan. The last question addressing compensation disparities merits its own extended treatment in a future post.

A note: Semantically loaded and/or outdated as the words ‘expat’ and ‘local’ might be -as compared to the more PC words “internationals’ versus “national workers’- my informants in Jordan used and preferred this way of differentiating among staff.

On the same team

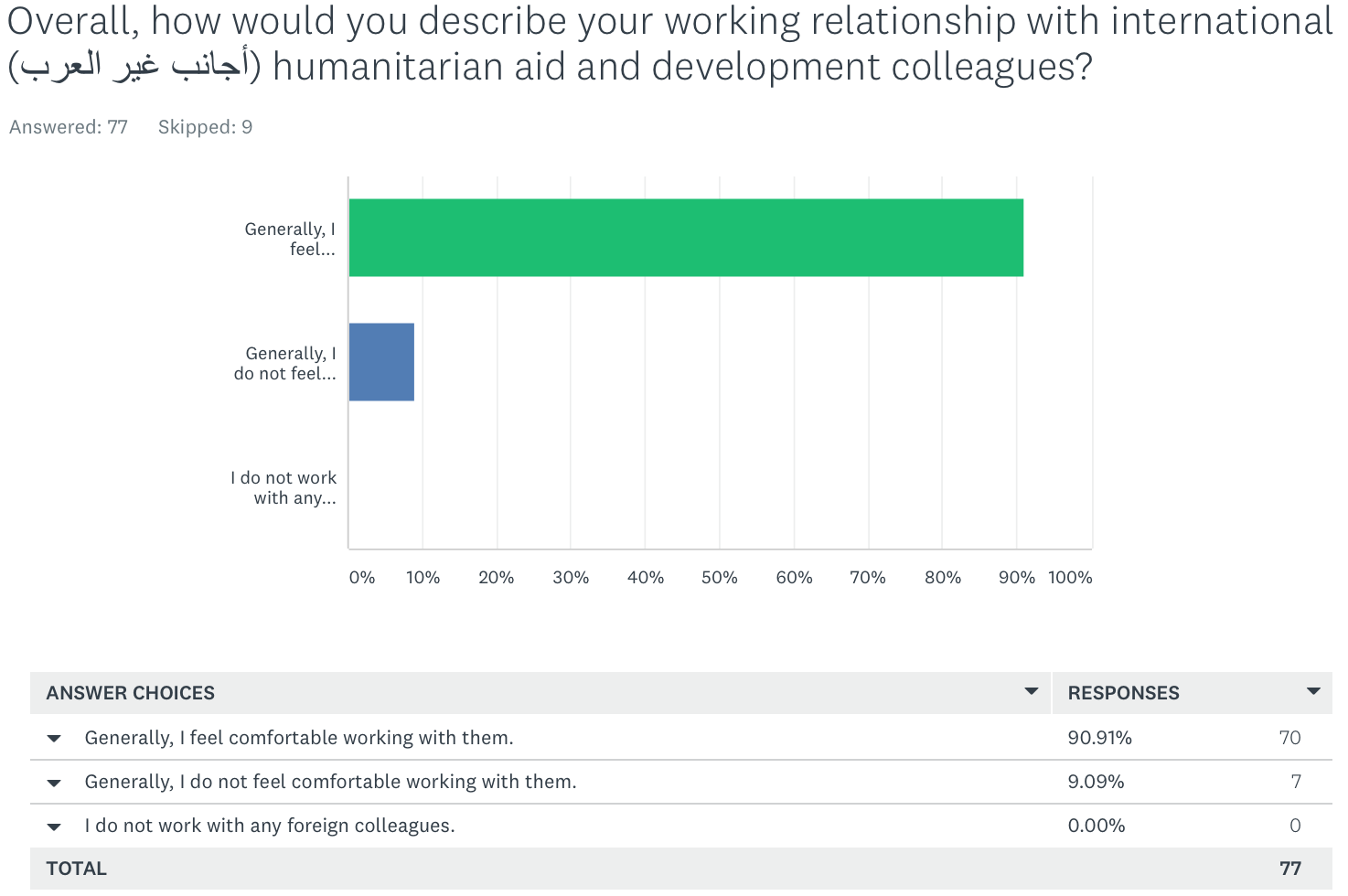

The intent of these first two questions was to get at how Jordanians felt about working alongside ‘international’ staff. The quantitative results to the question, “Overall, how would you describe your working relationship with international (أجانب غير العرب) humanitarian aid and development colleagues?” indicate the vast majority -91%- feel comfortable working with ‘international’ staff. That said, why do some not feel comfortable?

Here is what one young female wrote in the comments.

“I personally don’t differentiate in my relationships with internationals vs nationals. However, I am fully aware of the dimensions and the perceptions that (most) internationals have towards us (Jordanians/Arabs/”third-world citizens”), and that is what makes me rightly uncomfortable.”

Underlining what I mention above regarding power shifts, another said,

“Many of my colleagues are non-Jordanians. We get a long very well and respect each other. However, in general, the international humnaitarian/development sector places ‘expats’ at the top of the top of the power heirarchy and values their knowledge most, harkening back to colonial times I find. Jordanian women are often least valued in the sector. It’s a very much neo-liberal sector that discourages fighting back and speaking up especially on the part of ‘national staff.'”

This next comment adds to the colonial reference above, and adds a charged barb evoking the voice of Teju Cole,

“Other than the White supremacy attitude, particularly when working with a foreigner with amateur background, yet thinking that s/he is here to build the local capacity.”

Co-worker relationships set the tone in an organization, and tone can impact efficiency. The next comment by another young female explains why attention to these relationships matters.

“There are certain instances where it would be uncomfortable, sometimes us nationals are excluded from certain activities or meetings (even outside of work, just for being a national) and it really affects morale.

One last comment offered by a young female provides a very different and positive perspective,

“They [international workers] are mostly very professioanl and help elevate the level of professionalism, and quality of work being delivered. Many Jordanians treat their place of work like their second home and lack professionlism.”

How positive are your relationships?

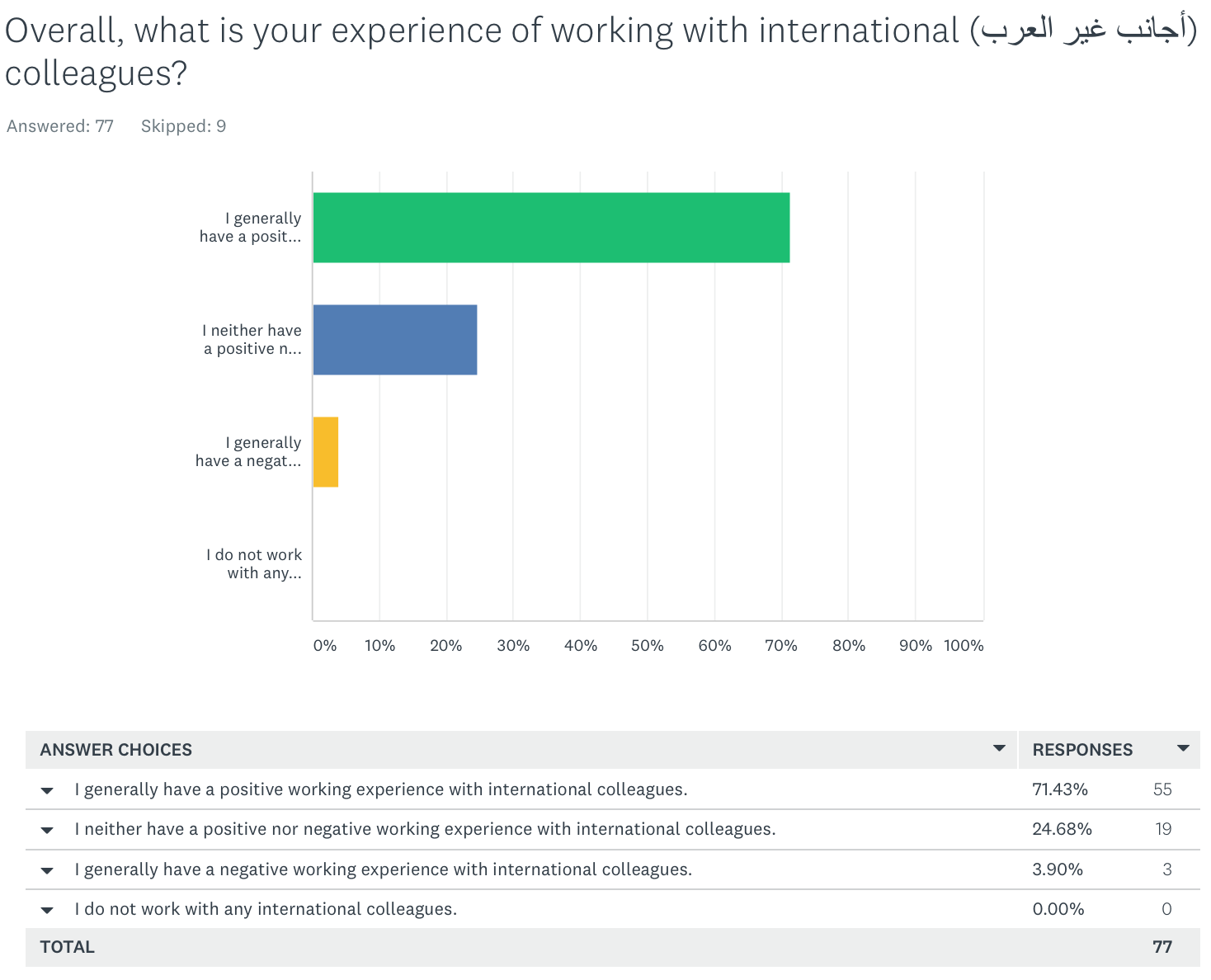

This first question in this section asked about comfort level, while this next question probes more deeply, allowing for a more nuanced view on the relationships Jordanians have with international workers. Prompting the respondent to put their relationships on an overall ‘positive versus negative’ experience continuum I asked, “Overall, what is your experience of working with international (أجانب غير العرب) colleagues?”

versus negative’ experience continuum I asked, “Overall, what is your experience of working with international (أجانب غير العرب) colleagues?”

The data are telling, and now we see a more tepid response with 71% indicating an overall positive working experience but with one in four -25%- indicating at least a mixed bag. Four percent described their relationship as negative. As with the first question, the comments offered are illuminating.

A thoughtful young female made this comment,

“I chose that I neither have a positive nor a negative experience because sometimes I do have a very positive experience but sometimes this experience is negative, or even harmful. Some have great, necessary capacities that are rare to find, or/and they are very hard working and spend so much time and effort (evenings/weekends…etc) working which justifies why they’re hired. However, some of them have very little/irrelevant experience, get paid a ton of money and stay in vast apartments (all are benefits they’d probably not dream of in their home countries), yet I hear them myself talking badly about Jordan and making really awful, insensitive, racist comments and jokes. There should be a system to whistle-blow those and make sure they are immediately expelled!”

And then this one, echoing a similar sentiment,

“I have inernational colleagues who are open-minded, respectful of my opinions and culture, interested in engaging intellectually even when things are challenging. On the other hand, I’ve equally worked with international colleagues who are so blinded by their “Western” sense of superority that it renders conversations with them ineffective and work with them very much predictable and disempowering.”

These two Jordanians express a common theme, namely, some [international workers] are good to work with, and some less so. In reference to the suggestion that there be a whistle blower system to call out racists, I’ll point out  that growing empirical research indicates micro aggressions -death by a thousand cuts- can and do have both mental and physical consequences. Both the efficiency of the workplace and the health of the workers are compromised when marginalization -however subtle or ‘unintended’- exists.

that growing empirical research indicates micro aggressions -death by a thousand cuts- can and do have both mental and physical consequences. Both the efficiency of the workplace and the health of the workers are compromised when marginalization -however subtle or ‘unintended’- exists.

How can the sector respond? I’ll quote AidWorkerJesus on this one, “Fewer workshops, my son. More wokeshops.”

That strains exist between ‘expat’ and ‘local’ aid workers in Jordan should be clear from the above. In a more perfect world we would have no comments like this, “Some of them are good people, some of them have hidden agenda.” But just as indicated by the #oxfamscandal and #AidToo movements we know sexism is baked into the aid sector, it is the same with racism.

My next post will present data from more survey questions related to ‘expat’ and ‘local’ relationships in Jordan. In the meantime, please email me if you have comment or question.

Follow

Follow