Some results related to gender and LGBTQ

Intro

Though there is much more data to sift through, this post will continue to add more depth to the picture of what aid and development workers in the Philippines think about a variety of issues. Go here if you want to learn about our methodology and the demographics of our respondents.

Background: gender equity in the Philippines

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Global Gender Gap 2016 report the Philippines ranked an impressive 7th out of 144 nations, number one in Asia, and has a long history as a matriarchal society predating colonial times. Just for comparison sake, you’ll find the UK at number 20 and the US at 45 in that list of 144 nations. Holding on to ‘last’ place in the WEF rankings, currently facing historic catastrophic humanitarian issues, is Yemen.

that list of 144 nations. Holding on to ‘last’ place in the WEF rankings, currently facing historic catastrophic humanitarian issues, is Yemen.

Much has been written about the impact of gender in the Philippines, and though many examples of male-dominated macho culture exist (see the current President), much of the social, economic, and political life is heavily influenced by women. Yet as the WEF report notes, there has been a global backpedaling regarding gender equity, and much work needs to be done, even in the Philippines. The waste and underuse of the human resources represented by women is a global issue, to be sure, and especially in developing nations like the Philippines that are hit regularly with natural (and partially human made) disasters. For deeper background on gender equity in the labor market in the Philippines go here, but you might want to have a doughnut first, just for some really deep context (at least from one perspective). But I wander.

The impact of gender

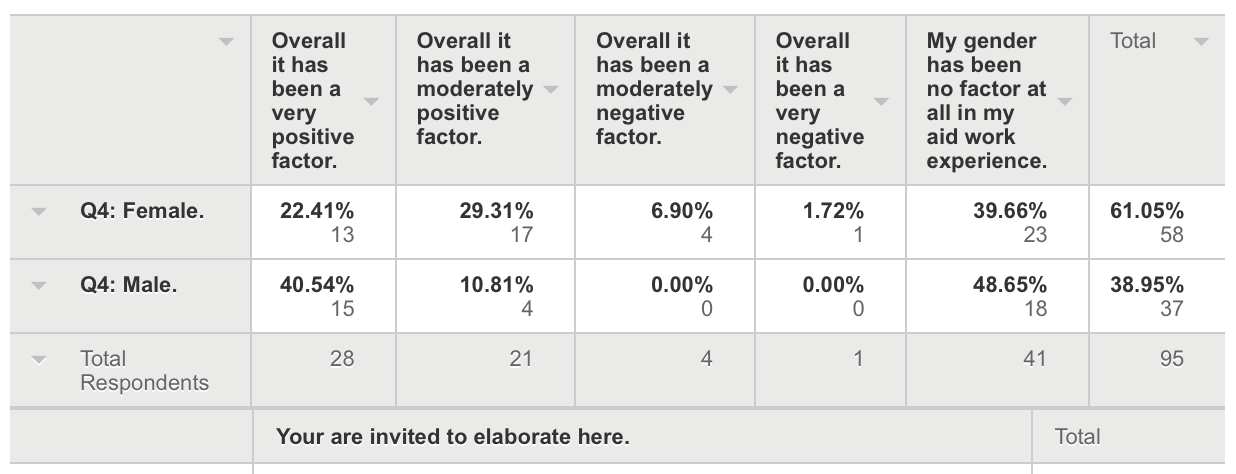

Responses to the question, “To what extent has your gender been a factor in your aid work experience?” provides some evidence that males have it a bit easier on the job than females, with males (41%) reporting their gender has been, “Overall a very positive factor,” more so than females 22%) almost twice as often. Adding the ‘very positive’ and moderately positive’ numbers for each, though, yields almost the exact percentages (51.72% females and 51.35% males). While no males reported that their gender was a negative factor, a combined 9% of the females reported this was the case.

This female, 10+ year local aid worker, captured both the positive and negative with her comment,

“Working in the field, many times people have said it is easier for beneficiaries to open up to women which has been positive. However, there have also been instances wherein I have been harassed (aggressively but mostly borderline) by colleagues and counterparts.”

A similar sentiment comes from yet another female, giving us a glimpse into the cultural nuances in play,

“I think my role entails a certain kind of charm/charisma when reaching out to possible partners from both ends of the spectrum–funders to grassroots community organizers. I believe that because most of my colleagues and the people I interact with are male, they tend to be ‘nicer’ and give in to certain requests more to a female requesting it from them (typical Filipino culture).”

One male noted, “I feel safer, overall, when doing field work than perhaps some of my female colleagues. I am less likely to be a target, being male. I have not experienced any direct bias for or against myself due to my gender.”

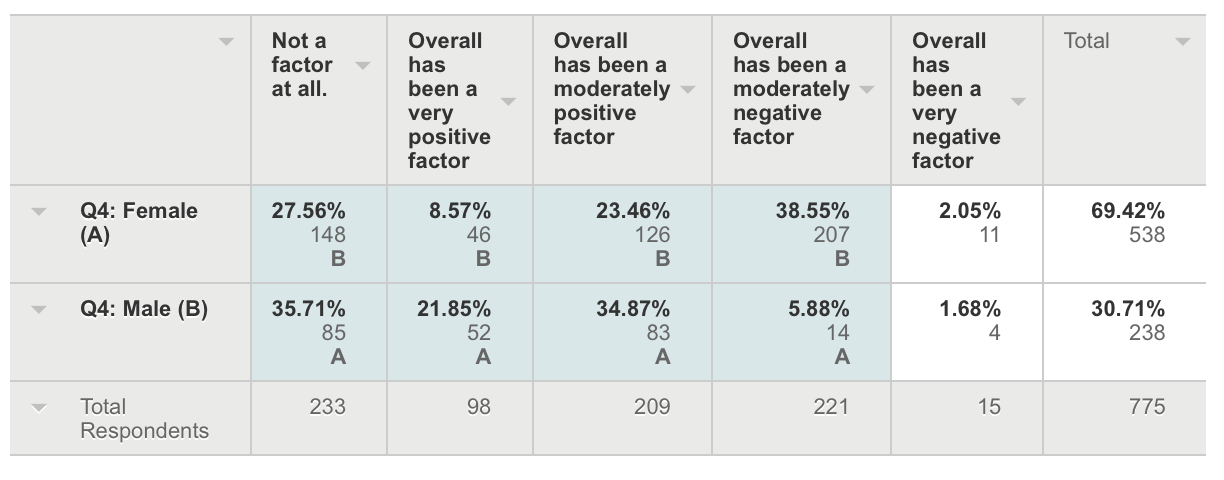

How do these data compare with our mostly expat 2014 numbers?

Even accounting for the wording changes in the question, data from the Philippines does contrast fairly dramatically with our 2014 data as you can see below. Over 40% of the 2014 female respondents seeing their gender as an overall negative factor compared to only 9% of the females in the Philippines. There are several possible explanations for this difference most of which are tied to cultural differences as noted above, but I think an addition significant factor is that at least while on deployment expat workers have more of a 24/7 work day, with work and ‘social’ life blurring together as compared to local aid workers who presumably can go home to family after work hours.

LGTBQ colleagues in the Philippines

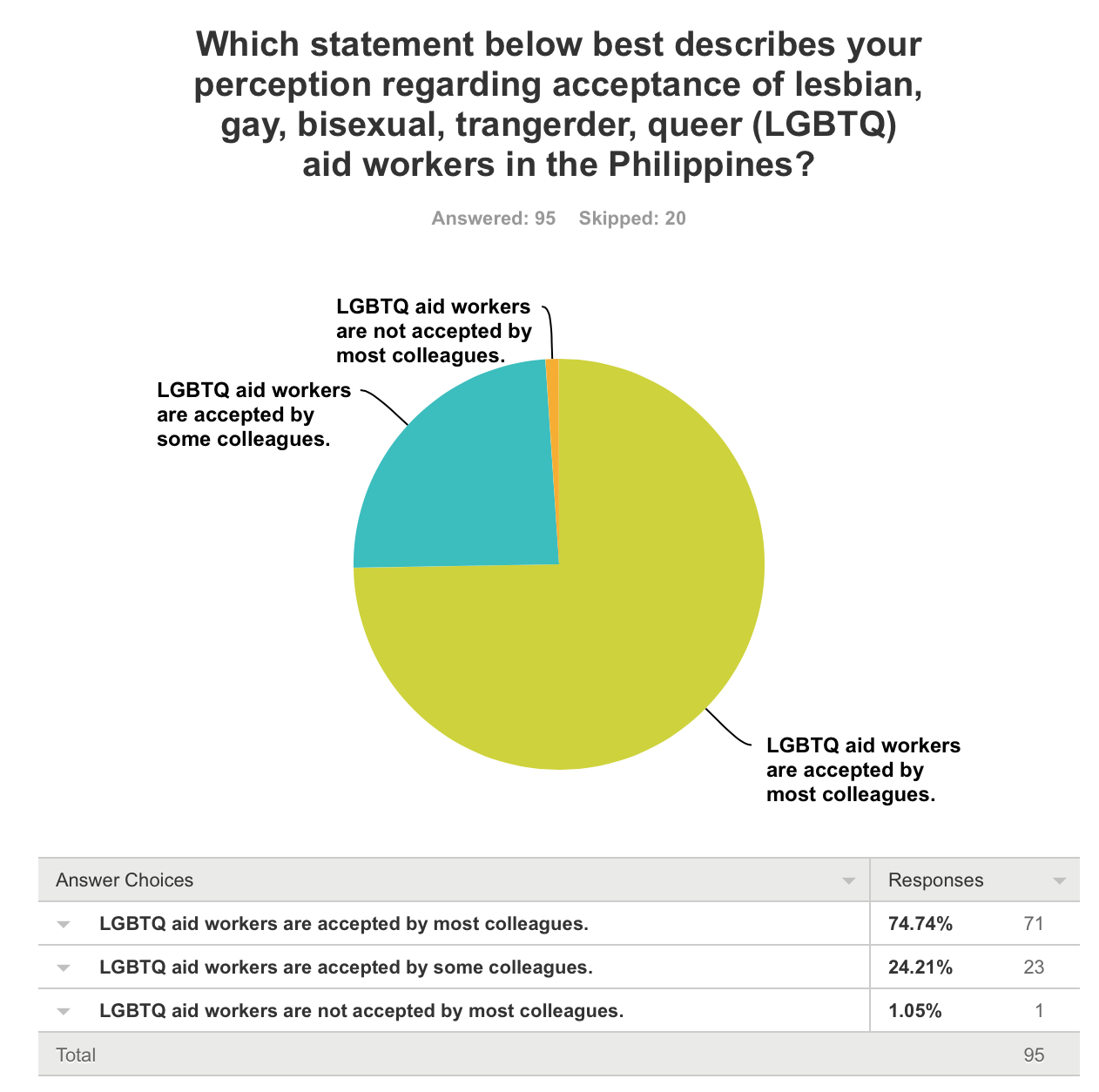

We asked, “Which statement below best describes your perception regarding acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgerder, queer (LGBTQ) aid workers in the Philippines?” and at least to me the results appear guardedly positive.

From the data, I get the sense that at least within the aid sector Filipinos are fairly accepting of their LGTBQ colleagues , with 75% reporting that, “LGBTQ aid workers are accepted by most colleagues.” That a significant proportion of those responding -25%- signaling that LGTBQ colleagues are accepted only by some or no colleagues is troubling and to me indicates that more focused research should be done on this topic.

, with 75% reporting that, “LGBTQ aid workers are accepted by most colleagues.” That a significant proportion of those responding -25%- signaling that LGTBQ colleagues are accepted only by some or no colleagues is troubling and to me indicates that more focused research should be done on this topic.

I did break the data from this question down by gender and found very little if any difference between how males and females responded.

One female aid worker noted,

“In my country, acceptance of LGBTQ aid workers is much easier if these workers declare their gender preferences at the start of their work in the orgn. Hiding their gender preferences is oftentimes unacceptable as this is considered as an act of deception.” Another wrote, “Gender is not a big deal as long as you are qualified to do the job.”

Here I posted about results from a smaller survey from (mostly) expat aid workers where a similar question was asked.

In my next post I’ll go further into the few -but suggestive- additional gender related differences.

Closing thoughts for just now?

These beginning dives into the data have been instructive, serving to underline the basic truism that “one size does not fit all.” Each nation has its own unique history and current state of affairs, all of which impact how the aid and development sector manifests itself locally. The tendency to make broad statements related to ‘local versus expat’ discussions remains, but one must be ever careful, always listening for important cultural nuances.

As always, contact me if you have any questions or thoughts.

Follow

Follow