Deepening the conversation regarding ‘local aid workers’

[updated 12 Aug 2018]

Guilty as charged

I have been researching and blogging about ‘local aid workers’ for a couple years now. (You can click elsewhere on this space to see my posts about national aid and development workers in Zambia, the Philippines, and Jordan.) In this short post I hope to deepen the conversation regarding ‘expat’ versus ‘local’ aid workers. My first act is to remove this phrase from my vocabulary, ‘expat versus local’. I must admit to being among those -guilty!- who are too imprecise in their usage of terminology, not just with this particular issue, but regarding many others relevant to the humanitarian ecosystem.

That said, the humanitarian aid system is an ever expanding and adapting global system that is extraordinarily dynamic and complex. Describing it with precision can be a bit like trying to grab smoke.

How to talk about the staff employed in the humanitarian ecosystem

Published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)/Policy Development and Studies Branch (PDSB), this 2011 report titled “Safety and Security for National Humanitarian Workers” gives a wealth of detailed information concerning the issues discussed in Pauletto’s BRIGHT magazine essay. Her offering, The Shocking Inequality in Foreign Aid That Nobody talks About, although doing a credible job of discussing several important issues, adds to the semantic muddying of the waters regarding the types of staff that are employed in the humanitarian ecosystem, reverting back to the comfort of the “expat versus local’ terminology.

Here are two relevant exerpts from the OCHA report. This first comment affirms the information the Pauletto article mentions that I gathered in Zambia regarding the ratio of international versus national aid and development workers. Understanding national aid workers is imperative given their numbers and obvious critical impact on the sector and, of course, on affected communities.

“National aid workers constitute the majority of aid staff in the field — upwards of 90 per cent for most international NGOs — and undertake the bulk of the work in assisting beneficiary populations.”

This next statement provides a valuable deepening of the defintion of ‘national’ aid worker.

“‘National staff’ can encompass a range of hiring categories that can stipulate different terms and conditions of employment. Increasingly organisations differentiate between local staff, hired directly from the area that they work, and national staff, nationals of the country but not from the duty station locale. In this paper, we use the terms ‘local staff’ and ‘nationally-relocated staff’ to distinguish between these two. In many organisations, local staff have different terms of employment, compared with their relocatable counterparts. Further, some organisations, including the UN agencies, will have different contracting arrangements, benefits and career tracks for nationals hired for ‘professional’ positions and those hired for general services and administration. Like in many NGOs, UN national staff can serve in senior management positions and ultimately become international staff working in other countries.”

As we all move meaningful dialogue forward on these issues, I am convinced that using OCHA’s more nuanced -and accurate- definitions related to national aid workers can take us away from simplistic ‘expat’ vs ‘local’ chatter and toward ever more productive discussions.

Not a homogeneous lot

In my interviews with national aid workers I have become keenly aware of the obvious, namely that they are not a homogeneous lot, but rather can be broken down into many useful categories as modeled above by OCHA above, e.g., ‘local staff’ and ‘nationally-relocated staff’.

An additional nuance immediately comes to mind, and I am tempted to use the language we employ here at my university, making the distinction between ‘administrative’ staff versus ‘support’ staff, the former being, generally, professionally trained personnel (e.g., administrators or accountants) and the latter being non-professional (e.g., housekeeping or grounds workers).

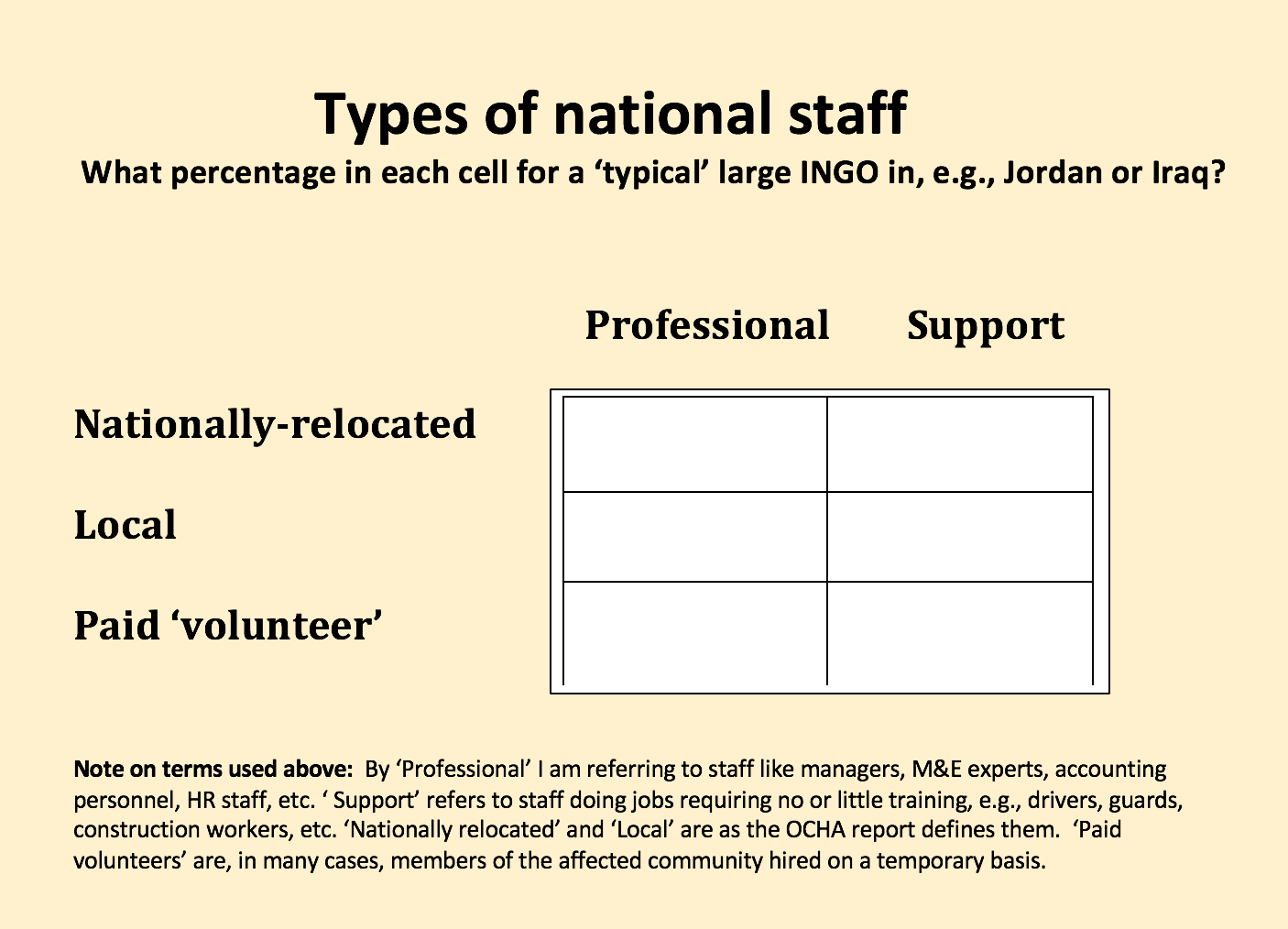

In picture form, I here pose a question question. At any single point in time, based on the table below, what would be the breakdown of all the staff ’employed’ (using as a working definition where employed = getting paid for work) by various INGOs? To national staff reading this post, where would you place yourself?

When discussing ‘local’ aid workers some of the distinctions suggested above may be useful. Regarding major issues like the degree of risk typically encountered, availability of vertical career pathways, or compensation packages (to just start the list), one’s place in the table above may be a good predictor.

This short essay by my fellow researcher Gemma Houldey (“Why a commonly held idea of what aid workers are like fails to tell the full story“) models a keen sensitivity to the various types of both international and national aid workers in Kenya. She notes that the differences in socio-economic status and living conditions “…between local workers and expatriates can be sharp.” Relevant to my illustration above, she notes that,

“In Turkana, Kenyans I spoke to had partners and families hundreds of kilometres away in another part of the country. They could only see them every eight to ten weeks, during their rest and recuperation, a compulsory break taken from humanitarian operations which usually lasts about a week.”

Being a nationally relocated humanitarian worker can be onerous, to say the least.

Adding yet another dimension to this discussion Houdley adds, “There is a racialised aspect to this too, with ‘expat’ still often conflated with ‘expert’, and in both cases they are primarily assumed to be white.”

An even more recent research article by Ong and Combinido (“Local aid workers in the digital humanitarian project: between ‘second class citizens’ and ‘entrepreneurial survivors’”) adds even more nuance. They examine “… the rise of project-based rather than long-term career aid work and the explosion of precarious digital work characterized by short-term dispersed labor (i.e. outsourced) arrangements.”

Somehow I must edit my “Types of national staff” illustration above to account for the critical issues highlighted by both Houdley and Ong & Combinido, perhaps paying more attention to the dynamic nature of this workforce and adding “project-based aid worker” into the scheme.

A short note on international staff

Just as national staff are demonstratively not a homogeneous lot, the same is so for international aid workers. The biggest distinction perhaps being between those that are from the ‘Global North’ and those from the ‘Global South’. Oft times an international staff might be from another country in the region, a Kenyan working in South Sudan or a Syrian working in Jordan, for example. That there are differences related to the factors mentioned above (degree of risk typically encountered, availability of vertical career pathways, or compensation packages) between these two categories seems apparent.

Much more to be said about the different types of both national and international aid workers, to be sure.

Onward

As I continue researching and working on hearing and then reporting on the voices of national (of all types) humanitarian aid workers, I will strive to improve the lenses through which I arrive at my questions and my interpretations of the answers.

I look forward to reporting on the final questions on the survey of Jordanian aid workers, but now with the suspicion that most that responded to the online survey are not representative of all the cells in the “Types of national staff” illustration above.

Any comments or reactions are welcome. Contact me here.

Follow

Follow