What is the “humanitarian aid system”

Context

This note is in part prompted by an op-ed piece in The Guardian by J in which he asks, “Is humanitarian aid really broken? Or should we all just calm down?”. J points out that, “The answer to ‘What can we do to fix the aid system?’ depends on what exactly you think is broken and what you think it was meant to do in the first place.”

Agreed.

But I would like to ask an even more basic question, namely ‘what is the humanitarian aid system?’ This question became very germane to us as we imagined our survey of aid workers, the discussion of which is the purpose of this blog. As a sociologist, the first thing I was taught in my research methods class was that before you sample and survey a population you have to, well, define exactly what that population is. In this case we are studying “aid workers” (hence the title of our blog AidWorkerVoices). But again, just who are these ‘humanitarian aid workers’?

question became very germane to us as we imagined our survey of aid workers, the discussion of which is the purpose of this blog. As a sociologist, the first thing I was taught in my research methods class was that before you sample and survey a population you have to, well, define exactly what that population is. In this case we are studying “aid workers” (hence the title of our blog AidWorkerVoices). But again, just who are these ‘humanitarian aid workers’?

Used as an adjective, as it is in this context, the simple dictionary definition of ‘humanitarian’ is “concerned with or seeking to promote human welfare.” To be accurate, then, an inclusive definition of ‘humanitarian aid worker’ would have to embrace a wide range of people approaching this goal of promoting human welfare from many directions and from a staggering array of organizational platforms.

That said, our data indicates that most respondents to our survey worked for what would be traditionally defined as humanitarian aid work, i.e., big budget, large global reach organizations.

Note

Here is what our sample population looked like, all self-identified and all presumably representing one time point along a career path. Less than 30% were what the public might stereotypically label “humanitarian aid workers”, the rest doing some sort of development-related work. Our phrasing of the question left much room for interpretation by the respondent, but I think it is interesting that most (53%) put themselves in the “development” category.

And now for this

Several points I want to make below, all interrelated and all critical to examine as we move forward in our efforts to understand and make more effective humanitarian actions of all kinds. These will come from my admittedly mostly US perspective, but nonetheless the points remain somewhat universal.

First, the humanitarian system includes innumerable points along a continuum from pure aid (e.g., emergency relief) to pure development. Ask those working for, say CARE in Ethiopia, to tell you exactly where aid ends and development begins and they will respond with a shrug. In the words of one aid worker, “…it’s always a challenge, especially in this context, in this environment, when does emergency begin, when is it development?” And so it is with many individual aid workers as they progress from one point in their career to another, sometimes doing aid, sometimes development, most times a blur of both or neither.

A second point is one that seems obvious and was underscored in Caroline Abu-Sada’s (editor) MSF commissioned book In the Eyes of Others: How People in Crisis Perceive Humanitarian Aid (2012). From the ‘beneficiaries’ perspective it really does not matter from where aid or assistance of any sort comes. Frequently, the outside entity offering immediate to long term ‘help’ is only perceived in the most vague manner; organizational messaging and logos remain an undifferentiated blur. That is to say, the ‘humanitarian aid system’ is a construct that can have very little relevance in the minds of those for whom the aid system’s efforts are intended. Imagine you are working on a development project in a certain community, then a disaster affects those same people: “sorry we only do development” does not seem a good way to lift them out of poverty. Luckily it is typically not the case, but you do have humanitarian actors that refuse to carry out development activities.

A third point, and one for which more detail is needed, is that actors within the humanitarian system include many entities and individuals outside of the traditional insider’s definition of what aid or even development is.

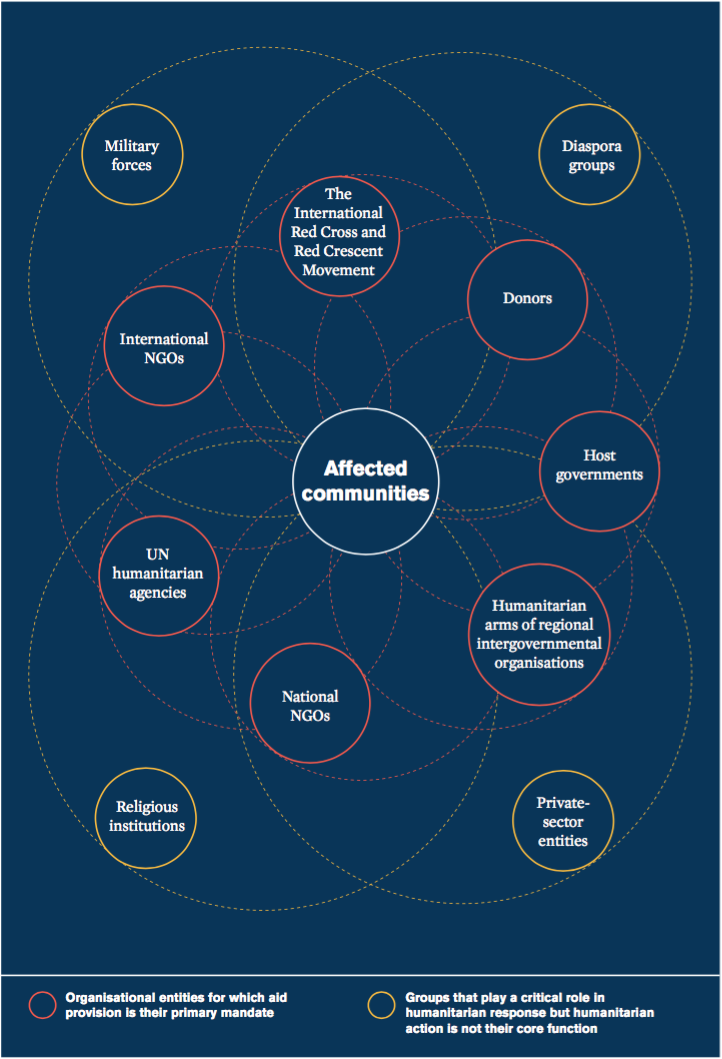

Although I agree with the wordsmiths at ALNAP (The Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action) who describe the humanitarian system as “an organic construct, like a constellation: a complex whole formed of interacting core and related actors.” I do feel that their model (below), elaborate as it may be, falls short of being usefully inclusive. Their premise is that aid work is a profession and their model thus emphasizes the 450,000 aid professionals worldwide.

To the extent that aid work is a profession -and I agree that it is and should be seen as a profession- there are umbrella entities like ALNAP that are taking proactive measures to both understand and make positive changes to the humanitarian aid system. Indeed, the establishment of the Core Humanitarian Standards, a product of the Joint Standard Initiative, is a positive example of forward thinking efforts.

agree that it is and should be seen as a profession- there are umbrella entities like ALNAP that are taking proactive measures to both understand and make positive changes to the humanitarian aid system. Indeed, the establishment of the Core Humanitarian Standards, a product of the Joint Standard Initiative, is a positive example of forward thinking efforts.

My point is that in reality the humanitarian aid system is far more inclusive than even the complicated ALNAP model infers, and this fact is ignored in discussions about “fixing the (broken) aid system.”

Expanding on what they include, here are some additional -though far from exhaustive- thoughts where new categories are suggested and some that ALNAP does mention are elaborated upon. These appear in no particular order. My reason for this is explained below.

- Peace Corps volunteers and their European counterparts from other typically Global North countries number in the thousands with impact in over 70 nations worldwide. They are doing -or at least are intending to do-humanitarian development work.

- MONGO’s (My Own NGO) -of which there is an increasing number. Many are US based, but this creating your own non-profit organization to help “save the world” seems to be a generally Western phenomena that is only getting stronger. Note for example the rise of social entrepreneurship programs in US colleges and universities and elsewhere fueling the rise in number of small non-profits. Though MONGO’s are largely a Western (and/or global north) phenomena these is a trend upward around the world of these entities, though some many have ‘ghost’ partners from the north.

- Everyday individuals, part of the global diaspora, sending remittances while working and living in the US or in other parts of the developed world. These funds -totaling as much as US$550 billion in 2015- are aid of the increasingly popular “cash transfer” nature and make a huge impact. Remittances from various diaspora account for a massive amount of ‘aid’, the total in USD dwarfing that of what is more traditionally thought of as ‘foreign aid.’

- All of the many Corporate Social Responsibility personnel working around the world. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is becoming more of a factor in the sector in ways that can no longer be ignored or marginalized. The 10 principles of the United Nations Global Compact to the cynical (read: realists) may sound like so much hot air, but increasingly the millennials and generation x students are making a change in CSR from within. In large part this is caused by a long term trend in higher education emphasizing community and global service in American higher education. Our own Periclean Scholars program at Elon University is an example where students who graduate from the program have global citizenship and humanitarian ethics embedded in their DNA and will take that into their profesional lives. In the last 15 year or more US higher education has had an increasingly central focus on “civic engagement and social responsibly”, indeed there are many consortia specifically devoted to just that (Imagining America, Campus Compact, Project Pericles, to name a few). Of special note along these lines is the long history that CARE has working with scores of corporations.

- Academic/service learning students from American colleges and universities doing aid and/or development work (the “service learning” mentioned above) during both short and long term travel abroad experiences count in the tens of thousands annually.

- Church groups from the US (mainly) doing ‘mission’ work and the many individuals doing 1-2 year outreach experiences (e.g., Mormons). European-based Catholic missionary work also continues apace. In many parts of the world massive sums of money go to ‘help the poor’ from church, temple or mosque coffers and/or is simply done by individuals whose motivation is to satisfy religious expectations.

- Civic groups such as Rotary International have a footprint around the world that cannot be easily measured but certainly is part of the mix.

- Though this is obvious, the impact of those affected by disaster and/or long term needs who help their family, friends, neighbors is massive. The families in Jordan and Lebanon, for example, who have absorbed refugees from Iraq and Syria are not only doing humanitarian aid, but arguably are the largest provider. These are all cross-national examples (either working outside of their country of origin, or working with foreign populations), but clearly there are many who do feed the malnourished or teach the illiterate across US (or replace US with virtually any other nation) communities, and this highlights how broad the community is.

-

People working for donor agencies, especially if headquarters-based. They often have technical expertise in humanitarian and/or development aid provision, and sometime travel to the field for monitoring missions, but at the same time they are not your typical aid worker. They spend most of their time in western capitals with their families, they have somewhat regular working hours. Some of them are actually employed by another entity (e.g. ministry of Health or of Agriculture) and only temporarily seconded to the humanitarian/development arm.

-

Consultants hired by external firms to provide for instance monitoring and evaluation of aid projects. Some of these firms focus solely on aid, but others work in several sectors. Are their employees aid workers? More broadly, how do we consider companies that are subcontracted to provide works/services for an NGO or UN agency in the framework of an aid project? Strictly speaking they are only doing business, not aid work. In practice however the type of activities they do (e.g. give out cash to beneficiaries, carry out a survey on beneficiaries’ needs, etc.) are indistinguishable from the same things done by “real” aid workers.

-

Civil protection/defense, fire brigades and other similar corps: they are usually among the first responders to emergencies. Sometimes they work together with humanitarians: for instance, the European Commission has a single structure that oversees both humanitarian aid and civil protection. Yet I would argue they are somewhat different, perhaps because their focus is “at home” rather than in third countries, but isn’t it a bit neocolonialistic? Similarly, military personnel also sometimes distribute relief or implement development projects to “win hearts and minds” (and they often label their own initiatives as “humanitarian”, as in the Balkans in the 1990s). But I would say they are not “true” humanitarian workers.

- Another example of work that is done to ‘promote human welfare’ though not direct and hence not traditionally seen as aid work are the efforts of those international organizations (like UN agencies) working with myriad governments doing normative work (e.g setting international standards or benchmarks) or developing capacity of national officials in, for example supporting the ministries of education or health in areas like planning or technical cooperation.

And the list goes on.

An organic construct

In short, the take-home from the above is as simple as this. “Fixing” the humanitarian aid system cannot be done. Period.

Why? Because, inclusively defined, the humanitarian aid system is not closed, involves (literally) innumerable entities and actors along a complex and fluid continuum, and many of these entities and actors by their nature transcend governance and policy influences of any kind. Systems theory 101 tells us that although you can limit your definition of what is or is not included in your model -in this case “the humanitarian aid system” -the reality as it is perceived by the beneficiaries is more complicated and must be accounted for as you assess impact and imagine changes. And a butterfly flaps its wings.

Take that, Joint Standards Initiative.

But there is hope. The ‘humanitarian aid system’ in any one particular geographic/cultural context likely does have a relatively finite number of entities doing work. Efforts to maximize the communication, coordination , cooperation and principled functioning among these players in any given location is a step towards ‘fixing’ the system. This will never be easy, simple, quick or, in the end, terribly effective. In the words of one aid worker, “the aid/hum/dev sector cannot be considered as a whole, so we basically have to pick what we think is broken, define and circumscribe, and fix it.” Paul Currion adds additional layers of complexity to this discussion in his article “The Humanitarian Future“.

, cooperation and principled functioning among these players in any given location is a step towards ‘fixing’ the system. This will never be easy, simple, quick or, in the end, terribly effective. In the words of one aid worker, “the aid/hum/dev sector cannot be considered as a whole, so we basically have to pick what we think is broken, define and circumscribe, and fix it.” Paul Currion adds additional layers of complexity to this discussion in his article “The Humanitarian Future“.

These local fixes will be by no means “one size fits all” in nature, and thus we’re always back to square one as we move around the globe, location to location.

‘Is the aid system broken?’, J asks. Well, yes in some specific and narrow cases, as he accurately points out. The humanitarian aid system is a growing, amorphous and uncoordinated array of ‘do-gooders’ being pulled by our natural human urge to respond to those in need, just as Henri Dunnant did in 1859 in Solferino.

We are both blessed and cursed with this very powerful urge, but we can at least deal positively and productively with the our humanistic impulses by taking a broader approach to defining the ‘humanitarian aid system’ and earning satisfaction at successfully, on occasion, protecting some of our castles in the sand.

Post scripts

Though I say above that there is hope for ‘fixing’ the system I really am far short of closure on that point. I invite you to read here and here for my thoughts about the very premise of humanitarian aid and to decrypt the reference to sand castles above.

Look soon for a second part to this post explaining why the humanitarian aid system is -all things considered- doing an amazing job.

Contact me with your thoughts, feedback or snarky comments.

Follow

Follow