Treated with respect and dignity?

[updated 14 August 2018]

Basic human needs

Humans have basic needs, among them are the obvious like food, water, shelter, and freedom from constant danger. These, largely material (or materially satisfied) needs, are the first focused on when people think about responding to communities at risk. Critically, in the minds of many both institutional and individual donors, once these needs are met the job is done.

How the above mentioned material needs are met is critical in determining the degree to which some vital non-material needs are met, namely the existentially critical necessity to have and to be treated with both respect and dignity.

An article authored by Valerie M. Meredith and published with the ICRC (“Victim identity and respect for human dignity: a terminological analysis“) says, in part,

An article authored by Valerie M. Meredith and published with the ICRC (“Victim identity and respect for human dignity: a terminological analysis“) says, in part,

“The notion of human dignity is central to the discourse of the ICRC and what it wants for the victims of conflicts–to protect their dignity. There are various facets to human dignity. They include a sense of self-worth involving self- perception and arguably a recognition of worth and a sense of belonging bestowed by others, be it the family or the wider community. In this regard, human dignity relates partly to one’s own sense of identity and worth. The act of recognizing the identity projected by a person is thus an act of respect for that person’s dignity and should therefore, in theory, be part of any humanitarian gesture.” (p. 270)

I would agree that yes, as inferred in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “Dignity is in the centre of humanitarian aid.” Here’s a short (30 seconds) video I made a few years ago featuring my Iraqi friend and colleague’s view on dignity.

The next several questions on the survey were added after in-depth discussions with Jordanian colleagues about “big picture” questions regarding the humanitarian imperative and how it related to responding to basic needs.

Responses from Jordanians

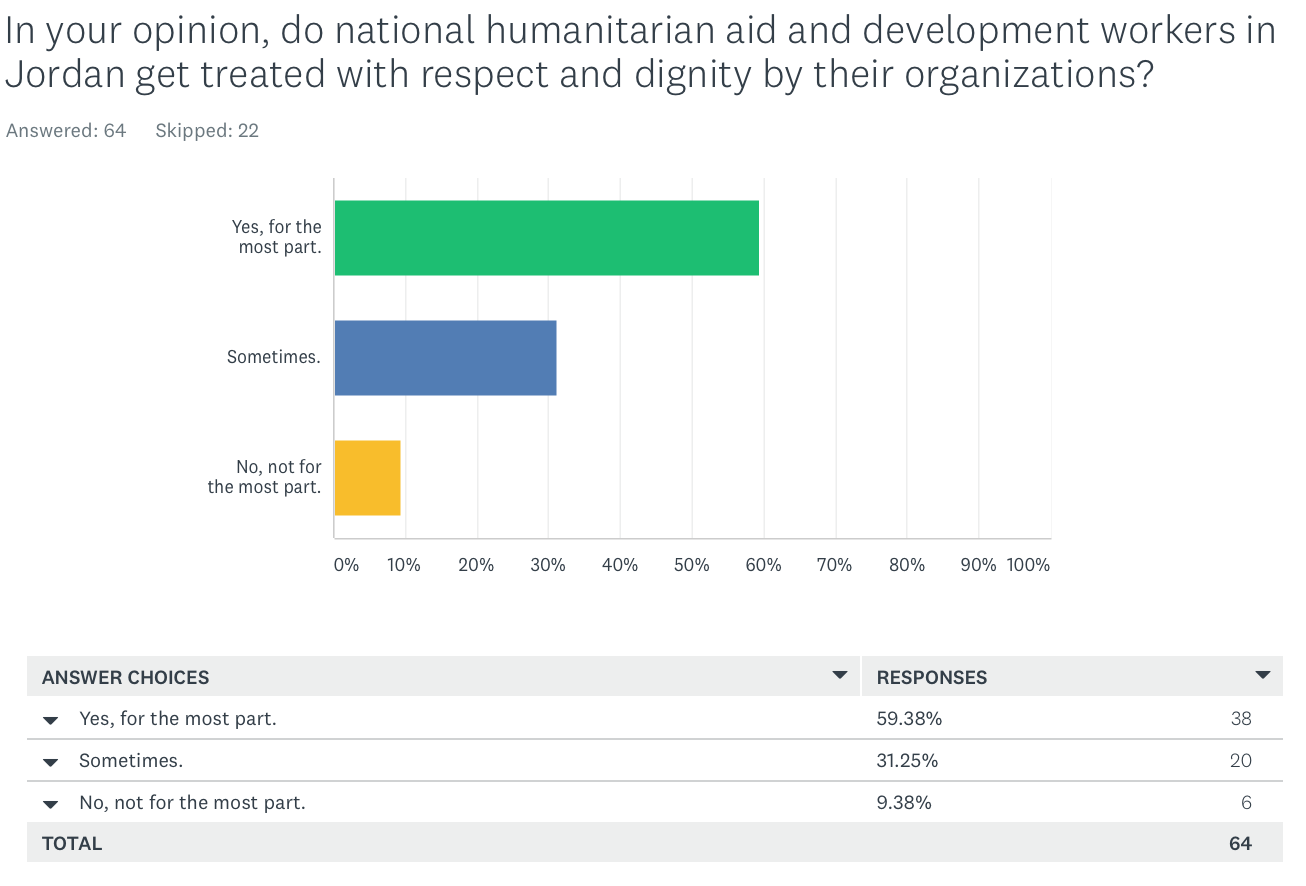

The survey offered three questions related to respect and dignity. Questions 38 and 39 went directly to the point, first asking the respondent about how they are treated by their employing organizations and then how the affected community gets treated.

“In your opinion, do national humanitarian aid and development workers in Jordan get treated with respect and dignity by their organizations”

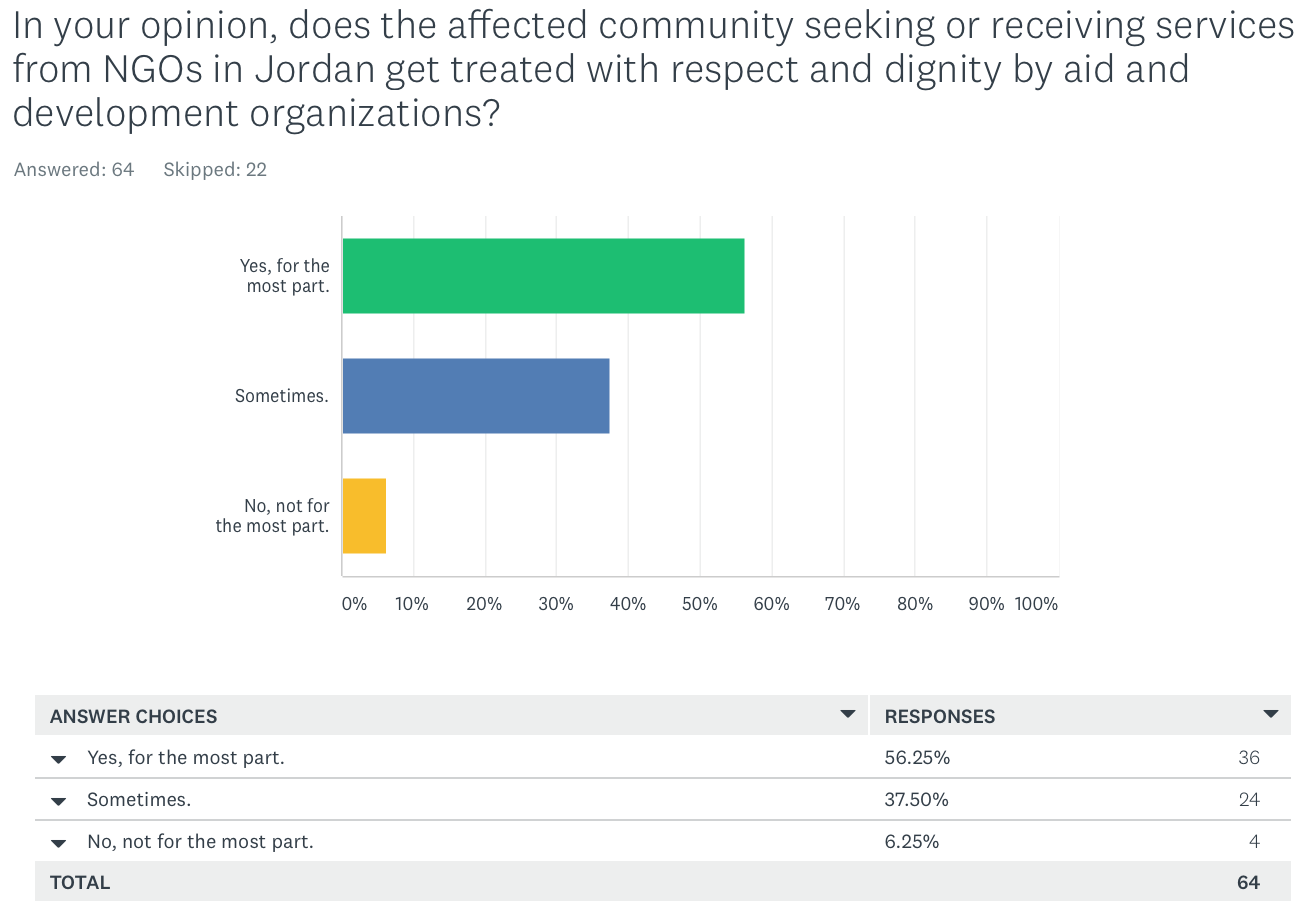

“In your opinion, does the affected community seeking or receiving services from NGOs in Jordan get treated with respect and dignity by aid and development organizations?”

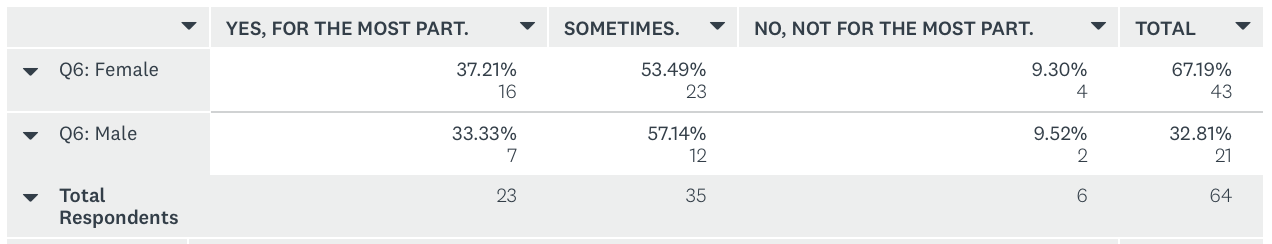

Q38

First, a look at how the aid workers felt they were treated. A strong 59% indicated they were treated with respect and dignity “for the most part” but that leaves a significant number -41%- indicating only “Sometimes” or “No, not for the most part.” My first response when seeing these numbers was “Wow.” The only comment I feel totally confident making about these data is that this is something that definitely needs more study. If I were an HR or Comms manager seeing these numbers from my national humanitarian aid workers I would pause and then begin to dig deeper into where these feelings are coming from.

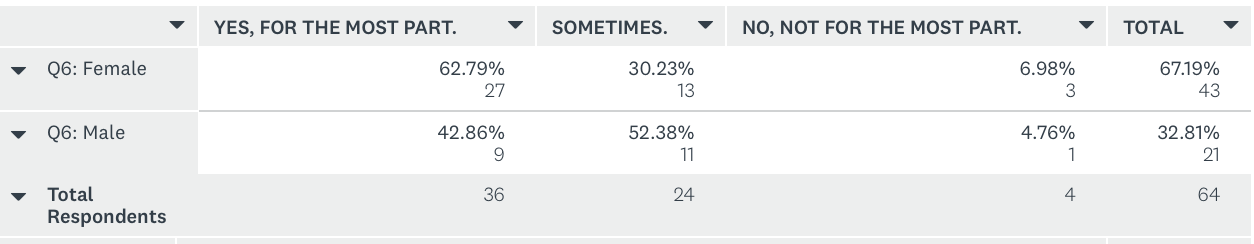

Q39

The next question looks at how the aid workers feel the affected community gets treated by the aid and development organizations, and the numbers are, like with the last question, give reason for pause.

The numbers are similar to the Q38, with 44% responding that the affected community gets treated with respect and dignity only “Sometimes” or “Not for the most part.”

Again, if I were in an INGO senior management position and saw these numbers I would be compelled to respond, at least with more questions and study. If I were a donor to an INGO, these numbers would, I think, be of concern, and more questions would be asked.

The third question

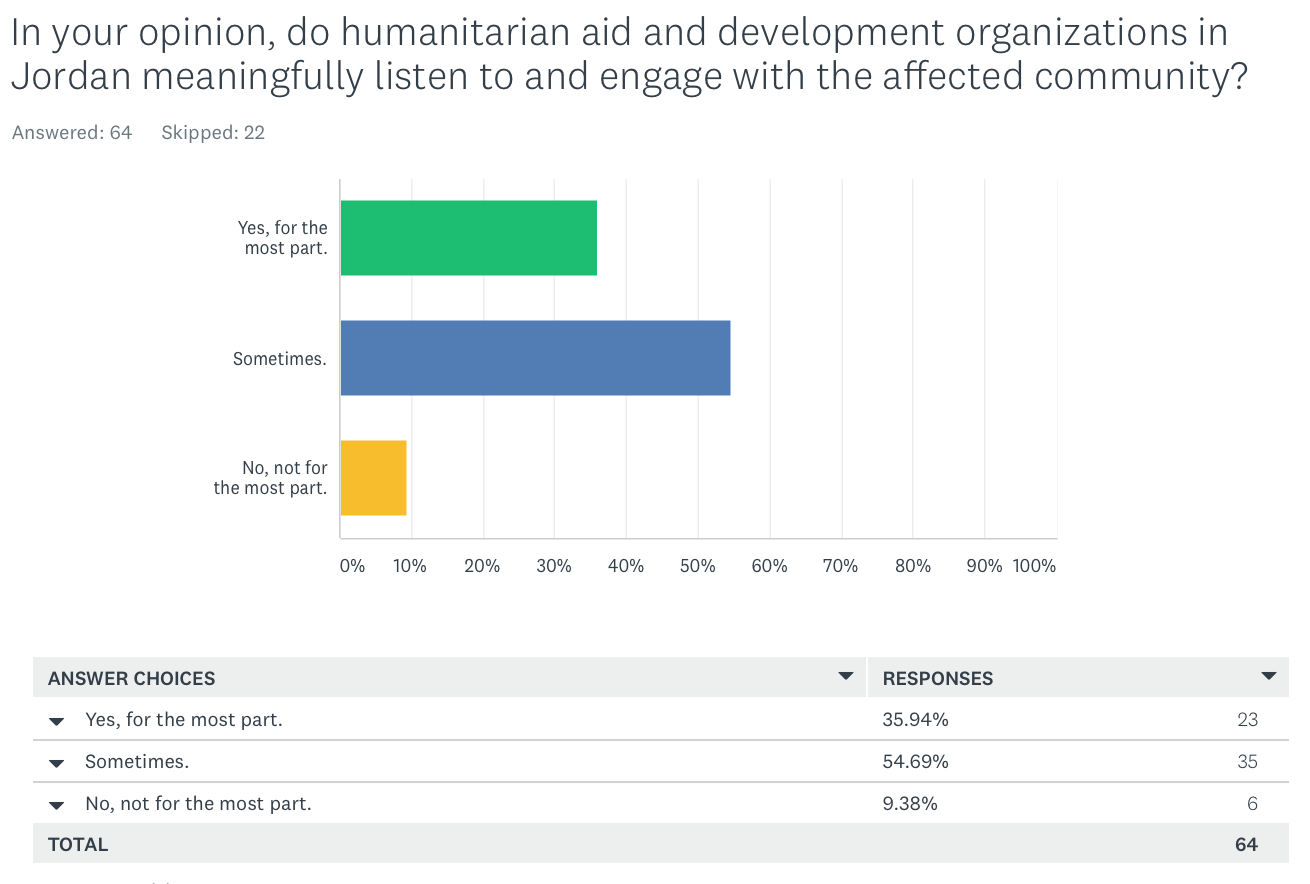

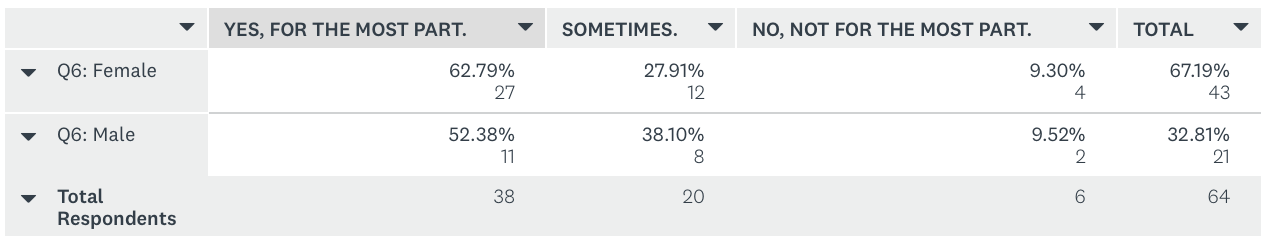

The next question on the survey asked, “In your opinion, do humanitarian aid and development organizations in Jordan meaningfully listen to and engage with the affected community?”

This question essentially asks the “respect and dignity” question again, though in a slightly different way. The numbers are even more stark. Nearly two thirds -64%- of the respondents indicated that the humanitarian aid and development organizations only listened to and engaged with the affected community only “Sometimes” or “Not for the most part.”

This question essentially asks the “respect and dignity” question again, though in a slightly different way. The numbers are even more stark. Nearly two thirds -64%- of the respondents indicated that the humanitarian aid and development organizations only listened to and engaged with the affected community only “Sometimes” or “Not for the most part.”

Giving great detail, here is what one respondent wrote,

“Not for the most part. Needs assessments are rarely done openly and curiously. They mostly are done to prove certain hypothesis and are made to do so. The needs are often pre-identified and the intervention is planned before any funds for needs assessments are available. In interaction with communities, dichotomization is often practiced to silence affected individuals from discussing certain needs that are deemed “non-relevant” or “too private” by the humanitarian sector. One example I recall very clearly being notified of is the need of adult refugees to have private time to be intimate without their children being in the same space as them. This was deemed too private and not fit to be discussed publicly and addressed publicly. Refugees were asking for Day Cares for their little children so they can find such time. Another very powerful exampel is the issue of religion. The industry is underequipped to address any religious discourse and reasoning that shape the minds of affected communities. Therefore, when religion and religious references are used in communities’ public discourse, organizations often try to bring it back to the ‘private’ sphere where they don’t have to deal with it and where it reinforces values the industry claims to engage with..”

Among other issues, this comment brings up the sensitive topic of religion, the social institution at the core of most cultures. The epic and inexorable tug of war between ‘objectivity’ and ‘ethnocentrism’ is extremely nuanced when taking on religiosity.

A second core issue raised in this response is that recognizing, honoring, and responding to agency, is certainly a critical dimension of respect and dignity. When asked to comment on these data Amelie Gagnon, a UN staffer working on education initiatives, reacted,

“One of my thoughts is that although professionals treat people with respect and dignity, we always need to make sure that the organizational purpose, or the meaningfulness of the programme being implemented, is aligned with the needs of the counterparts we are serving. In that sense, if context is not understood and no proper priority analysis is done, this can lead to the outcome of depriving the receivers of their agency, rather than straight dignity or respect. And it is probably just as problematic.”

In practical terms, fulfilling the humanitarian mission and responding to needs is never easy, linear, or perfect. Yes, there will always be issues, especially when it comes to the non-material needs we are discussing here.

Not a new story

For some, the phenomena that may be behind these numbers are familiar. In a 2017 discussion paper for ICRC” Engaging with people affected by armed conflicts and other situations of violence” the authors note,

“In recent years, there has been no shortage of literature on the systemic issues that prevent humanitarian organizations from meaningfully engaging with, and being accountable to, individuals affected by war and disaster. Institutional resistance to change, operational constraints, technical difficulties, the fear of devolving power and decision-making, the complex integration of localization processes and private sector partnerships… the list is, or should be, familiar to all.

What is lacking, however – and what this discussion paper hopes to contribute to – is how these systemic issues can be compounded in armed conflict or other situations of violence. Unlike natural disasters, situations of conflict or other violence bring with them particular characteristics that can both create and exacerbate challenges around engagement with, and accountability to, affected people.”

In one of the discussion’s “Recommendations for donors” the author teams notes suggests a need to “Strengthen the humanitarian-academic nexus.”

“In recent years, there has been more research into humanitarian engagement with communities affected by violence. However, there are still gaps between research and practice, as practitioners often feel that research generally focuses on what should change and why, without giving practical help as to how. As such, research and its findings often do not reach or resonate with practitioners.”

on what should change and why, without giving practical help as to how. As such, research and its findings often do not reach or resonate with practitioners.”

So, the Jordanian survey data reported above is no surprise to many, and the comment above makes me seriously reflect on the “so what” reaction many might have, well, to any data reported out from this entire survey.

A short note on gender

Prompted by reaction from one reader, I went back through the data for the three survey questions discussed above, filtering for gender. Those identifying as females were, on the whole, less critical than males.

Here are the numbers for Q’s 38-40.

The results broken down by gender in Q40, “In your opinion, do humanitarian aid and development organizations in Jordan meaningfully listen to and engage with the affected community?” yielded not much difference.

For Q38 you’ll note a significant difference -nearly 20 percentage points- between males and females, with females far more likely to indicate “Yes, for the most part” regarding affording respect and dignity. I find it striking that there is a 22% difference between females and males -30% versus 52%- when responding “Sometimes.” To a lesser degree we see the same trend in Q39.

Why? A very good question, left, for now, unanswered.

Concluding thought

Is the humanitarian sector consistently affording “respect and dignity” to both national staff and to the affected communities in Jordan and Syria? The answer must be no, given the data above. I have confidence that this failing is both known and being addressed with both professionalism and passion by staff at all levels within Jordan and beyond.

Please contact me if you have comments or feedback.

Follow

Follow