How does your LGBTQ+ identity affect your aid industry workplace experience?

Filling a gap

Our original survey did not target the opinions of those who identify as LBGTQ+. Toward the goal of making it possible for Aid Worker Voices to include this significant subpopulation, I did some additional interviews and, on the suggestion of several people, worked with my colleague J to construct a ‘mini-poll’ exploring the question “How does your LGBTQ+ identity affect your aid industry workplace experience?”

We began the online survey with these words:

The aid industry goes to great lengths to persuade itself and others that it is a champion for justice and equality in the world. The UN system, NGOs of all sizes and kinds, and individual humanitarians invest time, energy, sometimes even money to make the point that they are forever on the right sides of all the issues. If there is one apparent element of aid/dev/NGO/UN worker identity, it would be this notion that we are all open-minded and inclusive.

Since we’re all so open-minded, it would make sense, then, that our organizations are havens of peace and light, that our workplaces are sanctuaries from an intolerant and sometimes downright cruel outside world. Right?

There are many issues over which relationships and workplace tolerance can unfortunately break down (including in the aid industry): Nationality, ethnicity, religion…

In this mini-poll we’d like to take a look at how sexual preference and gender identity can play out in the context of the aid industry workplace. Specifically we’d like to discuss perceptions and experiences from our LGBTQ+ colleagues.

Note: Yes, we do understand that sexual orientation and gender identities and expressions are complex and personal issues that can vary in time. When we asked people what terms and acronyms they felt were most appropriate, we literally got a different response from every single person. For the purposes of this survey, we’re going with LGBTQ+ to refer to individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer or otherwise non-heterosexual, as well as trans.

Note: This survey is not limited to LGBTQ+ people. If you do not identify as LGBTQ+ yourself, we would like you to answer each question as you believe it applies to LGBTQ+ people in the aid industry or in your place of work.

Survey says…

The response to the survey has been good and the vast majority (96%) of those who gave their opinions are industry insiders and/or have an intimate knowledge of the sector, and 86% indicated that they identify as LGBTQ+. So, cred level appears high among those responding, which makes the voices shared worth a close listen.

The mini-poll contained ten questions, all but a few allowing for open-ended comments. As with our original survey (the data from which are reported and commented on in Aid Worker Voices), I was overwhelmed by the thoughtfulness with which some people responded.

So here are the results.

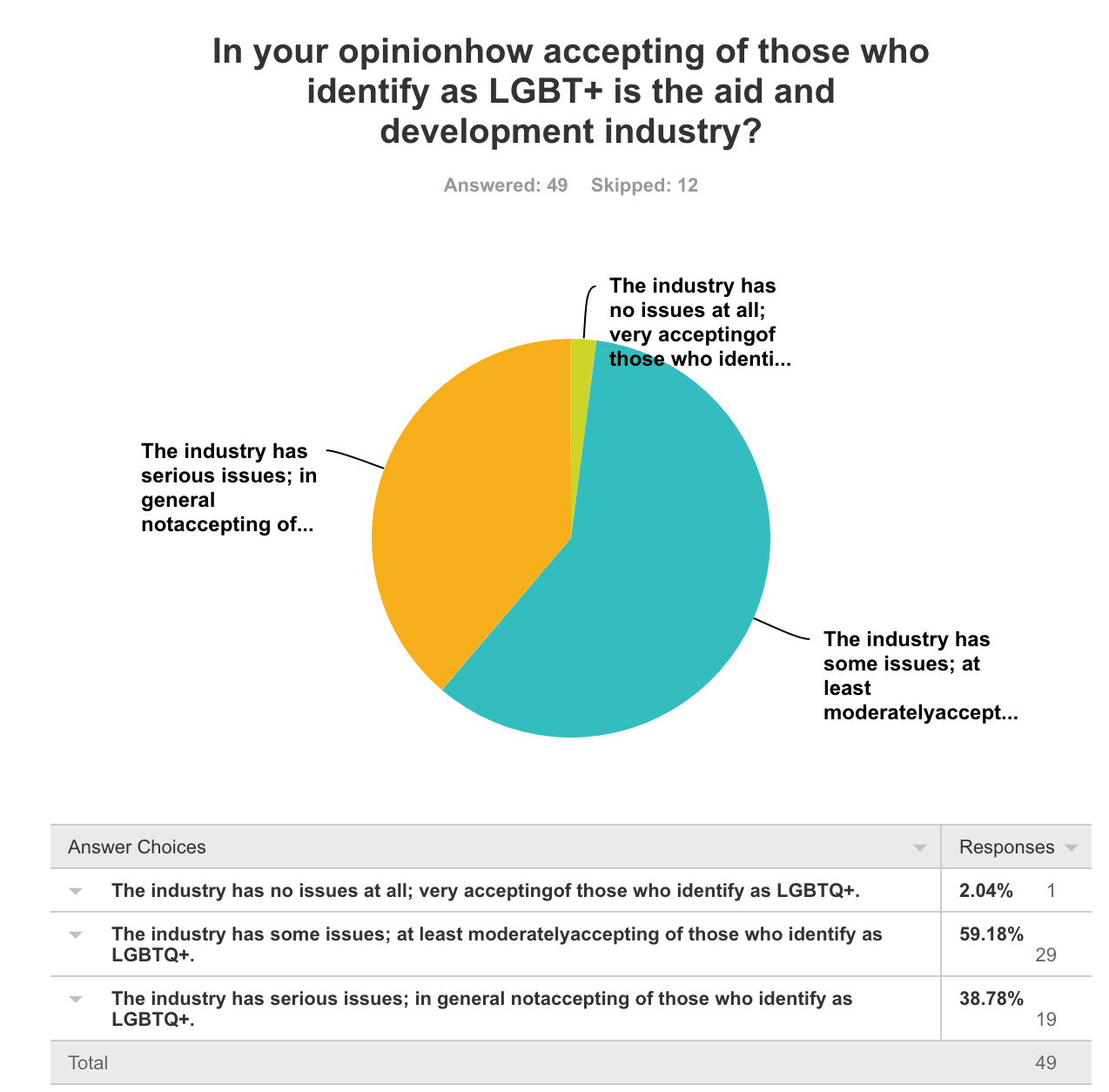

In response to the question “In your opinion how accepting of those who identify as LGBT+ is the aid and development industry?” predictably only 2% thought there were no problems which many -39%- indicating that the industry had serious problems. The fact that (1) the industry is very large and diverse and thus it is difficult to generalize and (2) there is a significant difference between the organization home base and ‘in the field’ was highlighted in some comments. These comments articulate well both points.

“There are obviously vast disparities between different organisations and different offices within the same organisation.

However, as an industry there is very limited recognition of LGBTI staff and/or how their security, health and well-being might be affected by their identity and orientation. So, although many individuals who work in this industry are accepting, the industry as a system is not.”

“While the AID industry in certain ways can be quite progressive in certain ways, it also continues to perpetate a lot of the same problems that underscore homophobia within our global discourse. It silences LGBTI staff versus raising their profiles or supporting the issues. They fail to understand the complexities of why Gender and sexual diversity issues, just like gender, underscores all development issues beyond just staff.”

“There is not enough programming for beneficiaries who identify as lgbtq nor is there enough support for national and expat (although a bit more) who identify as lgbtq.”

“There is a “culture” of general social justice, “the left”, and being inclusive but both institutionally and culturally humanitarian aid is much less accepting than it thinks it is. There is minimal support and knowledge of how to support and deal with LGBT issues that can arise in the field and generally LGBT people are just told to keep quiet and not cause trouble for their organization.”

So my read of the above is that though the sector may appear progressive it lacks complete followthrough on the idea that being inclusive means just that, and that if efforts toward this end fail to account for those who identify as LGBTQ+ there is still much work to be done. On this note, here is what one respondent said regarding a lack of action.

“Zero appetite for including LGBTQ+ in protection programming – at least explicitly- so little wonder that among staff the issue is largely ignored.”

But can the sector as a whole really pivot in a more progressive direction when there are many faith based organizations for which this type of inclusiveness flies in the face of religious doctrine? Said one respondent,

“I work for a Christian aid agency, some colleagues are homophobic and the organisation has an official stance against equal marriage.”

How many degrees of ‘out’ are there?

Are LGBTQ+ aid workers ‘out’?

Were we to live in a world of binaries that might be a simple question. We do not.

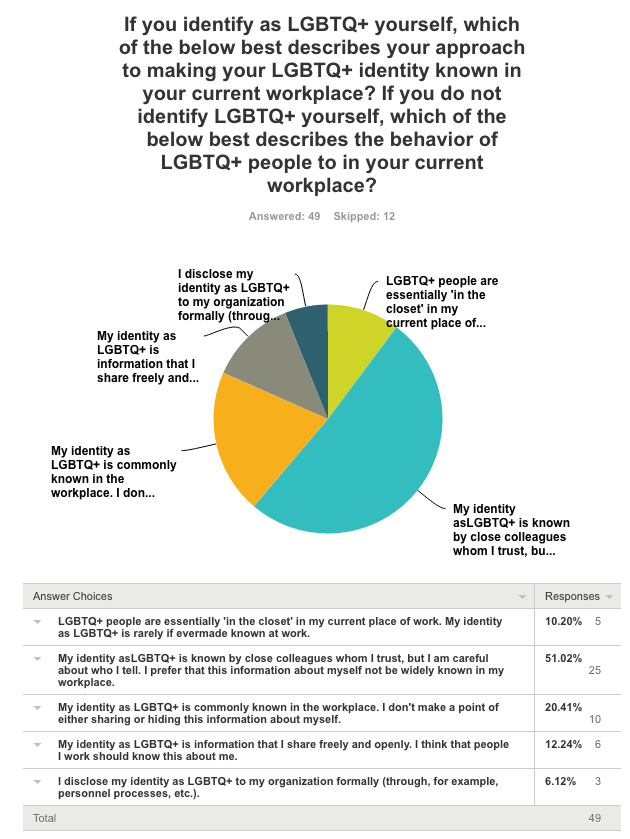

Here is what the respondents indicated, and as you can see there are many degrees of disclosure. In my field of sociology we make the distinction between ’emotional telling’ and ‘instrumental telling’, that is, between opening up to those with whom you interact because you care about them and vice versa and in telling others only for practical, necessary purposes (for example telling your dentist that you are HIV+). In aid and development work both kinds of telling happen and this varies considerably from situation to situation. While deployed in some areas of the world the decision to ‘tell’ or not can be critical. Listen to these next voices.

“I could possibly be forced out of my job in the Middle East at my (very large and respected NGO) because of my sexuality. They, in general, do not like the issues associated with having out gay men. There have been instances where gay male nationals who were too effeminate have been forced out of the organization.”

“I work for the UN and it has pro-LGBT policies and the environment is tolerant in HQ locations based on my experience. However, I have worked in E.Africa and many staff were highly homophobic – international staff – mainly from all over Africa. In my current field posting, many staff come from conservative countries or religious backgrounds that are homophobic, so despite working for the UN the atmosphere is entirely different from HQ and I have seen the bullying of LGBTQ+ and open homophobic comments.”

Our data were clear on this topic with the vast majority -77%- saying that “I feel more threatened, marginalized, or just offended from host governments, communities, and beneficiaries, etc. than in the workplace.” And even when your immediate workmates in the field are open-minded, there are still major safety and career concerns.

“I feel that I have open-minded colleagues in the field. I am openly gay to them but as they don’t have many other LGBTQ+ friends or colleagues, I worry that they may inadvertently put me in a difficult or dangerous situation. The management of my workplace have little appreciation of this challenge that I face. I wouldn’t be sure that they would stand by me if a homophobia incident caused a breakdown with a partner that threatened a project. They’d probably just move me to another project, and this wouldn’t necessarily be good for my career.”

“I feel that I have open-minded colleagues in the field. I am openly gay to them but as they don’t have many other LGBTQ+ friends or colleagues, I worry that they may inadvertently put me in a difficult or dangerous situation. The management of my workplace have little appreciation of this challenge that I face. I wouldn’t be sure that they would stand by me if a homophobia incident caused a breakdown with a partner that threatened a project. They’d probably just move me to another project, and this wouldn’t necessarily be good for my career.”

“I do not feel it would be safe for my career or wellbeing to be open in the UN compound and environment in which I work. Only the younger, western or westernised, professional level and higher educated colleagues seem to be non-homophobic and open. However, the majority of colleagues are not of this type and homophobic remarks are rampant amongs security, pilots, administrative staff etc. It sounds snobbish but it’s true. In my section I don’t feel threatened at all despite that some colleagues are a bit homophobic in general, despite being human rights workers. For national staff, homophobia is normal, nobody could ever be out to national staff here or anyone in the host community.”

Do managers make deployment decisions based on LGBTQ+ status? Here is what one respondent said,

“While difficult to substantiate, I believe that I have not been considered for a series of overseas assignments for which i was highly qualified, due to my status. I was once inadvertently included in an email trail from senior HR managers confirming that I would not get a post because of my status. This was extremely demoralizing to me from a career standpoint.”

Moving forward toward policy solutions?

In the final two questions of the survey we asked what could be done to move the needle in a more positive direction to make the work experience for those identifying as LGBTQ+ better. The responses were thoughtful and, in some cases, provocative. This respondent suggests what might be considered an unreasonable pathway forward given the fundamental humanitarian mandate to provide assistance as neutrally as possible. But, then, when and how do we make progress?

“Insist with the receiving countries that all staff be accepted without reference to race, gender or sexual orientation. Easier said than done, but someone needs to set an example. I believe that if the state discriminates against its LGBTQ minority, it should be sanctioned by the HRC and denied development/aid assistance.”

Many respondents suggested something along the lines of “change HQ policies to have them explicitly include language -and put teeth to that language- protecting staff identifying as LGBTQ+.” One went on to include the point that beneficiaries need also to be considered.

“I believe more funding and programmes should be available for this very vulnerable group. In displacement or refugee settings, LGBTQ+ communities are often twice or thrice times the victims or prejudice, assault and socio-economic vulnerability.”

This next respondent who sums up much of the above while making a specific suggestion.

“The UN bureaucracy needs to get over its squeamishness about the ‘third sex’. It needs to take a much more principled stance with member states that persecute their gay citizens through punitive laws and state-sanctioned violence. Perhaps its time for a “UN-Gay” organization to emerge that will lobby for the rights and interests of 10% of humanity? But good luck getting funding! On a personal level, I genuinely feel that my career prospects have been stymied by my coming out at work and that senior managers in my organization do not feel empowered to support my advancement. I also feel that HR will only ‘reward’ those who remain closeted and single. Of course, prevailing attitudes in the UN reflect the membership of 193 states, the majority of which are socially conservative. But aren’t we allowing the membership to dictate policies that only add to the prevailing climate of prejudice against LGBTQ people? The UN needs to lead by example and adopt truly inclusive policies that really do assist its gay employees.”

I’ll end this section with the touching and very personal words from one soul willing to share. Certainly many aid workers sacrifice, but perhaps LGBTQ+ bear an additional layer of psychological pain.

“Intimacy is the biggest hurdle. Imagine going for months without any expression of a deep part of your personhood. It is isolating and safe spaces are definitely needed.”

More details from a happily married gay woman

One veteran development worker took the time to address the questions in the survey with a bit more detail.

“The degree to which the aid and development industry is accepting of LGBTQ+ people is a tricky question, and the answer has an individual and an institutional level.

Let me explain part of the complexity. Although the organisation I am familiar with includes in their staff rules that everybody should embrace diversity, not discriminate, and respect each others differences. At least officially there is a safe space created for everybody to be who they are, so technically, the industry -or at least my organisation- is quite open and welcoming to every kind of person really.

But the reality is that these same organisations have offices in many countries where there is State-sponsored homophobia – so de facto, LGBTQ+ people (or at least myself) are excluding themselves from employment opportunities by fear of being harassed, threatened, or even jailed (this happened to someone in Senegal, because they were gay). If one wants to progress in their career, try something new, get other experiences, it might be difficult to rotate if you identify as LGBTQ+.

Last year I contemplated a post in Nairobi. Knowing that Kenya criminalises homosexuality and that social climate might be hostile regarding this issue, I had to ask myself if I wanted to put my wife in such environment, and most importantly our child. So we considered living apart (i.e. in different countries), moving in Nairobi with a gay male couple (to pass as two straight couples), living in a high-security bubble, only interact with like-minded expats —we seriously considered even the craziest options.

I have no trouble in serving in countries that have laws that I am against, but will I put my family at risk for sheer career progression? I am not able to take that step. I am lucky enough to be based in a European capital, and I get to work in countries where I could never dream of living in with my family.

What I have become to realise is that when I was a more junior professional, I tended to avoid social situations from colleagues, especially colleagues that I could not have ‘checked’ if they were open or not on social issues. Not so much because I would fear their reaction, but mainly I guess because I would not want to deal with the awkwardness of having to explain. Once, I introduced my wife as ‘my wife’ to a colleague and right there, in front of us, she literally replied “what do you mean?” That was awkward.

Now, older? Wiser? That I am positioned in a more senior position? In another country? I feel that I do not owe anything to anyone and that I do not have to deal with their reaction, basically.

In my office, everybody knows I am gay: peers, supervisors, interns, etc. It’s a relatively small office where we are all very social, so from the start it was a no brainer for me to be transparent about my personal life—and I felt very free about it. At my HQ, also, as soon as discussions become personal, I am absolutely open about being gay. I take it for granted that if someone asks about my intimate life, they are able to deal with any reality that it might entail. If not, too bad for them.

By contrast the reality is that when I work with my clients, outside of my organization, I am absolutely mute on my spousal situation. The great thing in having a child, is that I can redirect any discussion (or just focus on) things about children. That’s my joker. And I don’t need to lie.

What I try to do is to position myself as an ally to anyone who is not ‘conforming’. There was a colleague in one of our small country offices that I thought was gay – others were teasing him about not being married, and I could feel that he was not so comfortable with the teasing so I supported him not to be wishing to marry (quoting my grandma: “don’t get married!”) and made a case about living one’s own life etc. Then a few months later, colleagues were still teasing him about not being married, and then he said he had found someone but that this person ‘did not fully meet his family expectations’ or that it was something like ‘socially impossible’… and I was like “I knew it!”… but what happened next is that he basically declared he was in love with me. And then I was like ‘this is soooooo wrong, if he only knew’!

I don’t really feel threatened or marginalized, in the field than when back at HQ but I do feel in the closet with my clients, and totally free with my peers, colleagues, supervisors, etc. In fact, one thing I find very comforting is the fact that my office peers with whom I am open (out of the closet) are very sensible and sensitive to potential threaths to me when we travel together — when discussions fall into very heteronormative issues or when I am asked about my “husband”, colleagues do not hesitate to tag with me in adding more nuance, or even to help me protect my cover. I find this unspoken alliance very sweet!

What could the industry do to change for the better the work experience for those who are LGTBQ+? Perhaps there is a distinction to make between single, couple, family LGBT situations. Single people can deal with their lives themselves, perhaps. For couples, there might be a need for the employers to facilitate or help with employment of the partner… but for families, I really do not know what would be a workable solution. The only concrete thing I could see the industry doing is to lobby on government to abolish discriminatory legislation, so at least people can feel safe, or at least not threatened by law.

Being gay absolutely limits your posting/ employment opportunities when you have a family. If I were single, I would probably be ok to take a few years of potentially dry spell, or try something new:)

But when you are not alone, the professional benefits have to be weighted by the living conditions on your family, and that is not easy. I am happy because I get to travel frequently to work with my clients, while being posted in an open city, but I do see the limitations on my career.”

Others in the closet?

As a final note I’ll mention that as part of this research process I interviewed a number of aid and development workers who live in a parallel closet, namely those who are atheists. In particular, many non-believers who happen to work for faith based organizations feel compelled to play the game of ‘passing’ with their colleagues and superiors, remaining ‘closeted’ atheists, as it were. That there are laws against nonbelievers in some countries and that the lives of ‘out’ atheists are in danger -as is the case in Bangladesh- cannot be ignored, especially given the fact that there are likely more atheists in the aid sector than there are LGBTQ+. A final take home point here is that we need all to work toward a world where there is tolerance for all and that a ‘you be you’ attitude is more globally accepted by individuals, organizations and governments.

I am not holding my breath on that happening anytime soon, though.

Follow

Follow