By Jessica Mohr

On a sunny morning in late October, my travel group and I set out in my mom’s Chevy Avalanche for a day-long road trip around central North Carolina. From Elon to Lexington, we enjoyed taking in the sights of I-40, a busy, industrial road linking countless towns and cities together. However, the real adventure didn’t start until we hopped on Highway 64 heading out of Lexington. I-40 is great for getting where you need to go in a timely fashion, but this stretch of 64 through Franklinville and Ramseur is more for sightseeing and enjoying North Carolina’s great fall beauty, unless you live out there, of course. The tops of the trees are just beginning to turn orange, yellow, and red — a striking contrast to the sharp blue sky against which they are set.

Driving on 64 through this rural section of the state was a welcome change from the more developed and crowded cities I’ve come to call home: Apex and Elon. By no means are either of these towns a bustling metropolis, but they are certainly busier than downtown Ramseur, NC. While driving through both Franklinville and Ramseur, we hardly encountered any traffic, even though we were there around lunchtime. Pedestrians waved cordially to us, giving the impression that these were towns where everyone knows everyone, and newcomers/tourists/visitors are few and far between, except when related to long-time residents. Ramseur’s defining characteristic was mainly its evident history as an industrial town; old factory buildings and mills lined the roads, and regardless of how long they’d been abandoned or repurposed, they still bore the name associated with that previous life proudly.

Unfortunately, the roads that wound through Ramseur made one of our travelers a little motion sick. After stopping on solid land (read: an empty Arby’s parking lot) until she regained her equilibrium, we rolled out once again, this time aiming for my hometown of Apex! This stretch of 64 was one that I was significantly more familiar with, as I’d been driving on it since I was old enough to have a learner’s permit. As we got closer to the new Chipotle off 64 just past the demolition site that used to be my high school, I was able to put on my tour guide hat! Granted, I didn’t know any super interesting historical facts about the highway or the places we were going by. My tour guide knowledge consisted mainly of things like “that’s the neighborhood where my best friend from high school lived! She’s now off getting a doctorate in how to save the world from Stanford,” and “this is the new toll road, we’re all pissed about it because it’s only a toll road around Apex/Cary and is free everywhere else.” Local tidbits are my specialty, not a broad historical perspective.

After a delicious lunch stop, we loaded up the truck once more for the final leg of our drive – Apex into Raleigh. Since my house is 20 minutes away from downtown Raleigh (15 on a good day), this was a blissfully short drive, comparatively. Remarkably, none of my travel group mates had ever been to Raleigh! On again went my tour guide hat. We drove the length (and width) of the city center multiple times, being sure to circle the Governor’s Mansion multiple times until we could all get a peek at it through the large, leafy trees obscuring most of the view. We also saw the courthouse, museums, convention center, and the beautiful tree mural that shimmers in the wind. Since we couldn’t let a trip into Raleigh not include sampling the local food, we stopped at a small bakery called Lucette Grace, which was a fun combination of French rustic and sleek modern lines on the inside. After snapping some photos and each filling one of the bakery’s bright yellow boxes with 8 assorted macaroons, we meandered back to the truck to head home to Elon, all with a better understanding of how this historic highway winds through the Piedmont region.

neral direction, and we were met face-to-face with Lindsay Deal: the man behind every aspect of the growing, harvesting and marketing for one of the largest, and oldest, apple orchards in North Carolina. His face was colored initially skeptical, noticeably sizing us up as outsiders. Upon a brief explanation, however, he was more than compliant to talk about North Carolina culture across the Foothills. He opened that same wooden door he had come through just a few minutes age before, and invited us into his office.

neral direction, and we were met face-to-face with Lindsay Deal: the man behind every aspect of the growing, harvesting and marketing for one of the largest, and oldest, apple orchards in North Carolina. His face was colored initially skeptical, noticeably sizing us up as outsiders. Upon a brief explanation, however, he was more than compliant to talk about North Carolina culture across the Foothills. He opened that same wooden door he had come through just a few minutes age before, and invited us into his office. single seller who would then sell their apples to the major grocery chains.

single seller who would then sell their apples to the major grocery chains.  ’s competition has tapered out over the years, leaving just three or four primary orchards to spearhead the Foothill markets. Lindsay and his team have their process down to an absolute science and are Good Agriculture Practices-Certified. If you find yourself traveling through Alexander County, be sure to stop by the Deal Apple House and get a taste of what this family’s combination of passion and expertise has produced.

’s competition has tapered out over the years, leaving just three or four primary orchards to spearhead the Foothill markets. Lindsay and his team have their process down to an absolute science and are Good Agriculture Practices-Certified. If you find yourself traveling through Alexander County, be sure to stop by the Deal Apple House and get a taste of what this family’s combination of passion and expertise has produced. across abandoned-looking towns, and several fruit stands, you will see the scen e emerge from around the bend: the infamous Lake Lure, zig-zagging around rugged mountain ranges.

across abandoned-looking towns, and several fruit stands, you will see the scen e emerge from around the bend: the infamous Lake Lure, zig-zagging around rugged mountain ranges. Lake Lure’s public garden, passing couples holding hands and babies in strollers–caught in the aura of simple contentedness. An aerial view of the lake exposes a quiet gazebo in the distance that looks out to one of the most beautiful views along Highway 64. The contrast between the mountains and lake may remind you of the changing North Carolina landscape along Highway 64, shifting between the coastal plains, foothills, and mountains.

Lake Lure’s public garden, passing couples holding hands and babies in strollers–caught in the aura of simple contentedness. An aerial view of the lake exposes a quiet gazebo in the distance that looks out to one of the most beautiful views along Highway 64. The contrast between the mountains and lake may remind you of the changing North Carolina landscape along Highway 64, shifting between the coastal plains, foothills, and mountains.  he lake. Rather than imagining yourself on the set of

he lake. Rather than imagining yourself on the set of  n nature. Perhaps take one last look back at the mountains, soon to return behind you. A pillow of smoke catches your eye, curling from the top of the mountain in a small patch.

n nature. Perhaps take one last look back at the mountains, soon to return behind you. A pillow of smoke catches your eye, curling from the top of the mountain in a small patch.  s a rich taste of North Carolina history and tradition. Yet the expectation of the town on a Sunday late afternoon–everyone would be leaving church, taking the dog for a walk, or going to lunch on their day off–was disrupted by a quite different reality.

s a rich taste of North Carolina history and tradition. Yet the expectation of the town on a Sunday late afternoon–everyone would be leaving church, taking the dog for a walk, or going to lunch on their day off–was disrupted by a quite different reality. oughout the street from a series of unseen speakers. The music could be described as a marriage of jazz piano and elevator music, perhaps meant to be a nice backdrop to the sounds of engines and human voices. The bizarre ambience, one reminiscent of a post-disillusioned movie, would still not be the main source of disappointment in Lenoir. The greatest disappointment offered by a quiet Sunday in this town, is that a walk along the main street revealed Lenoir has a lot to offer. Amongst a few cafes, the town’s GOP headquarters, and small markets, it seemed every other storefront was an art gallery or antique shop–both retailers for town character, personality, history, and secrets. In an eclectic collection of castaway personal belongings and artistic expression, these are the shops that give define Lenoir local flavor. The storefront windows were decorated with autumnal displays, from puppets, to art easels made of birch branches, to leaves and twigs perched with fake birds. Yet each was closed. Not a single site was open. Walks around square blocks, the real estate turning to banks and insurance fronts the farther the sidewalk talks you the center of town, and a feeling of defeat sinks into the sunny day.

oughout the street from a series of unseen speakers. The music could be described as a marriage of jazz piano and elevator music, perhaps meant to be a nice backdrop to the sounds of engines and human voices. The bizarre ambience, one reminiscent of a post-disillusioned movie, would still not be the main source of disappointment in Lenoir. The greatest disappointment offered by a quiet Sunday in this town, is that a walk along the main street revealed Lenoir has a lot to offer. Amongst a few cafes, the town’s GOP headquarters, and small markets, it seemed every other storefront was an art gallery or antique shop–both retailers for town character, personality, history, and secrets. In an eclectic collection of castaway personal belongings and artistic expression, these are the shops that give define Lenoir local flavor. The storefront windows were decorated with autumnal displays, from puppets, to art easels made of birch branches, to leaves and twigs perched with fake birds. Yet each was closed. Not a single site was open. Walks around square blocks, the real estate turning to banks and insurance fronts the farther the sidewalk talks you the center of town, and a feeling of defeat sinks into the sunny day. one finds Charlie’s Pub. It seemed the Pub shared the same menu as the Bistro, but with a different wood-panel and booth atmosphere. A table at the back of the restaurant sat regally, occupied by a family of 10+ dressed up in what looked to be church gear as a long table. Off to the side sat a priest and two elderly women, dressed to the nines, sharing lunch and forkfuls of pie.

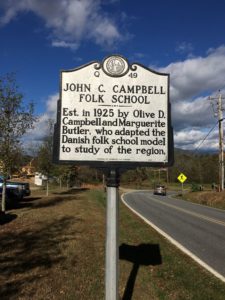

one finds Charlie’s Pub. It seemed the Pub shared the same menu as the Bistro, but with a different wood-panel and booth atmosphere. A table at the back of the restaurant sat regally, occupied by a family of 10+ dressed up in what looked to be church gear as a long table. Off to the side sat a priest and two elderly women, dressed to the nines, sharing lunch and forkfuls of pie. Past a gas station screenshot from the ‘60s was the town of Brasstown. Composed of a mail center, library, and gas station, the surrounding hill was a collection of homes bordered with signs encouraging the election of Trump/Pence.

Past a gas station screenshot from the ‘60s was the town of Brasstown. Composed of a mail center, library, and gas station, the surrounding hill was a collection of homes bordered with signs encouraging the election of Trump/Pence. Embedded between conversations of life and relationships, he spoke about the history of the Folk School in milestones. Between the dedicated commitment to working the land and building a new system of education was a history of community. His work focuses on documenting the stories of the people who populate the folk school. He mentioned that his interviews from the past few years have been especially interesting since he is recording and telling the story of the grandchildren he originally spoke to in the formation of the folk school in the 1920s. The motto of the folk school, as seen by the countless signs and embossing is “I sing behind the plough.”

Embedded between conversations of life and relationships, he spoke about the history of the Folk School in milestones. Between the dedicated commitment to working the land and building a new system of education was a history of community. His work focuses on documenting the stories of the people who populate the folk school. He mentioned that his interviews from the past few years have been especially interesting since he is recording and telling the story of the grandchildren he originally spoke to in the formation of the folk school in the 1920s. The motto of the folk school, as seen by the countless signs and embossing is “I sing behind the plough.” The crafts of the folk school were varying in discipline and medium. Kaleidoscopes, mosaics, and pottery sprinkled the wooden show room with color. Their craft store was composed of aisles of colorful art crafted throughout North Carolina. Each stand of work had the name of the artist and the home of the craft on a small paper in front of the pieces.

The crafts of the folk school were varying in discipline and medium. Kaleidoscopes, mosaics, and pottery sprinkled the wooden show room with color. Their craft store was composed of aisles of colorful art crafted throughout North Carolina. Each stand of work had the name of the artist and the home of the craft on a small paper in front of the pieces.