By Andrew Scott

Leaves of red and gold fell slowly down from the tree tops to the watery ground of the Roanoke River. The cool fall wind wisps and bites at the neck as one walks along the boardwalk and trails of the wildlife refuge. Regional birds chirp in the distance. The movement of the leaves in the wind haunt the otherwise silent forest ecosystem. The leaves drift down the slowly moving river, meandering across the flooded coastal plain toward the great release of the ocean. The scene here in Williamston is much like the rest of the coastal plain, swampy and wild.

North Carolina has a large tributary system that dumps a variety of rivers into the Atlantic Ocean up and down the coast. While these rivers may gush and flow frantically in the mountainous and piedmont regions, they alter their path drastically when they get to the coast. They ease their way into the ocean, creating seas of swamp land, maritime forests, and transportive ecosystems. One can easily image Native Americans and colonists traveling up and down these maze-like systems. The rivers slow to almost a lethargic halt, yet are more alive than ever. Some of the most abundant wildlife in the state can be found in these flooded refuges, giving off an almost otherworld affect. Kin to the Everglades or the Bayou of Louisiana, the Roanoke River and the greater Dismal Swamp area distinguish this area of the state from the others.

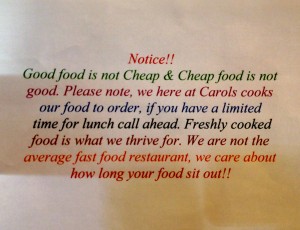

The sandy beaches and barrier islands of North Carolina play a huge role in the tourist interpretation of the region, but the clear majority of the region is haunted and founded on these traditions born in the swamps. The region is established on a vast habitat for animal life and human interconnectivity with the environment. The colonists had to accept these harsh terrains and find a way to survive in them, knowing that beating Mother Nature isn’t an option. The same rings true today, with the smaller coast plain communities bending to the will of the river systems. Adjusting to the flooding and movements of the environment, living off the land, and a disappearance of much of the modern essence of life takes place in these small towns. Highway 64 itself bends and flows with this land to create a seamless ecosystem. The protective services of the Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge are a major part of that.

Protecting the “219 birds, 33 mammals, 37 reptiles, 39 amphibians, and 59 fish” different species is critical to the environmental survival of the area. Without these foundational citizens of the waterways, the system would crumble. The current Roanoke River refuge contains around 20,978 acres of land protected; however, expansion of the park area is up for proposal. In this proposal, the National Wildlife Refuge tries to incorporate the members of the community into the act of saving the ecosystem. They additionally, look at the situation from a climate change viewpoint and a rapid urban development projection. All in all, much like other environmental pieces the Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge is an essential region of North Carolina heritage that is in danger of elimination.