Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh has become the largest refugee communities in the world as of February 2019 to over 900,000 Rohingya people who have fled their home country, Myanmar due to violence.

The History

Myanmar is a predominantly Buddhist country located in Burma with almost 90% of its inhabitants practicing Buddhism as of 2017. The Rohingya represent the largest group of Muslim people within the country (only approx. 1 million Muslims total in comparison to the approx. total population of 54 million in Myanmar). There has been tension between the groups for decades since at least 1948 after Myanmar gained independence from Britain. It is reported that a Muslim rebellion began in the Rakhine state as Muslims wanted a degree of self-governance with equal rights, but ultimately they were defeated. They haven’t been considered residents of Myanmar since the citizenship law was passed in 1982, which recognized 135 ethnic groups within the country, the Rohingya not being one. That rendered them stateless and they were denied citizenship, the right to vote and basic human rights, including education and health care (Hunt).

The conflict erupted in October 2016when a Rohingya insurgent group of around 300 men, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), is reported to have attacked border posts and kill 9 police offers. Retaliation led to around 87,000 Rohingya people fleeing to neighboring Bangladesh. Another attack on August 2017 reported that the ARSA targeted over 20 police outposts and killed 12 security officers (Hunt). The military retaliated on the Rohingya people as a whole and survivors recount the burning of their villages, their families being separated, murders (even “house by house” killings), torture, and the rape and gang rape of women and girls (Myanmar Rohingya). The military’s response has been what the UN considers an example of “ethnic cleansing” (Wong).

I do want to note that Myanmar denounces the accusations of genocidal behavior, some highlighting that they are the victims of violence by the Rohingya. Most are reported to be unsympathetic to the plights of the Rohingya and many have taken to calling them “Bengali” as a slur highlighting that they are immigrants and not native to Myanmar’s lands (Hunt).

The Crisis

“The crimes we have heard echo those committed in Rwanda and Srebrenica some twenty years ago. The Security Council acted in those two situations. It acted too late to prevent them which is all to our lasting shame but it did act to ensure accountability,” British U.N. Ambassador Karen Pierce told the council (Nichols).

From the over 700,000 Rohingya people in Cox’s Bazar during 2018 and now over 900,000 in 2019, the humanitarian crisis is hard to combat due to the vast number of people and scarce resources. The Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG), who are under the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR – United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) report in their 2018 Join Business Plan that their key needs include:

-

access to safe, clean water (16 million liters needed daily)

-

diphtheria and measles outbreaks have occurred and there is increased risk of acute watery diarrhea

-

contamination from fecal matter is also a concern

-

-

waste management

-

food (malnutrition at acute emergency levels)

-

physical care (particularly obstetric)

-

education (5,000 classrooms needed)

-

decongestion and relocation

-

access roads

-

agriculture and reforestation

-

access to cooking fuel can help combat the overuse of firewood resulting in environmental degradation (JRP For Rohingya)

-

Assistance with psychological trauma and subsequent distress is necessary as well. The camps in Cox’s Bazar are also in vulnerable areas where they’re potentially exposed to monsoons, landslides and flash floods. Early rains can also increase the risk of disease outbreaks. The areas being densely populated puts them in further danger of cyclones, rain and fires as well. The UNHCR has reported that $950.8 million is needed for relief efforts (Bangladesh).

Outside Countries Involvement

This crisis has definitely been covered globally with most calling for change. As of April 2018, the U.S., France and the U.K. were major nations that condemned the actions of the Myanmar government and pledged aid assistance to Bangladesh. The U.S., in particular, imposed economic sanctions in August 2018 on the Myanmar security forces. China is one major nation that is behind Myanmar (which many speculate is due to their economic interest within the country) and they’ve regarded the actions of the Myanmar government as an effort to “maintain domestic stability”. China and Russia have even attempted to protect Myanmar from sanctions from the United Nations Security Council in October 2018 (Nichols).

Aid Needed and Received

The aforementioned 2018 Join Business Plan prepared by ISCG details their aid efforts in subsections, highlighting participating organizations and funding requirements beginning on page 83 (JRP For Rohingya). The major categories include:

-

Food Security

-

Health

-

Shelter and Non-Food Items

-

Site Management

-

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

-

Protection

-

Education

-

Nutrition

Two of the most recognized INGO organization assisting in various areas are the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Action Against Hunger (AAH). The ISCG has established coordination hubs where response workers can meet regularly and collectively decide on humanitarian efforts. Assessment procedures are currently in place to identify major needs and account for the distribution of resources, including population monitoring (this is the first time many Rohingya have even received legal documentation), food security surveillance, landslide and flood risk mapping, education and child protection assessment and more. Response efforts are currently in place to target all 8 categories outlined above.

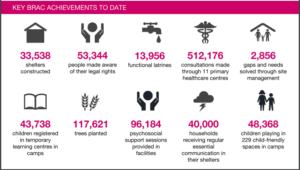

BRAC in particular, who has worked in Cox’s Bazar for 35 years, is cited as the number 1 NGO in the world by NGO Advisor. They published a detailed newsletter of their efforts in November 2018. Key achievements highlighted are noted below:

AAH identifies immediate priorities in Cox’s Bazar as well and their efforts have included daily distributions of food and water, emergency health care for malnutrition, waterborne disease prevention and improving sanitation, and mental health “first aid” (Rohingya Refugee Crisis).

Medecins Sans Frontieres, also Doctors Without Borders, is another organization, not mentioned in the Joint Response Plan, but who have humanitarian aid assistance in Cox’s Bazar. They have provided 1 million consultations as of February 2019, including treatment for acute watery diarrhea, diphtheria, antenatal and postnatal care, measles and mental health. Their site makes mention of the circumstance in Cox’s Bazar shifting from an “an emergency situation to a protracted crisis” (The 5 Things). A lot of treatment was initially for injuries suffered in Myanmar and basic healthcare, now injuries are more caused by accidental incidents. Yet, unfortunately, sexual gender-based crimes are still occurring.

Are Needs Being Met?

The population in Cox’s Bazar refugee camps and the region where they reside make aid efforts difficult, but the reports I’ve encountered show support from many organizations in all highlighted vulnerable areas. Access makes receiving, storing and distributing aid a challenge, but there are dozens of aid groups working to not only assist with emergent and immediate needs but also work toward establishing sufficient systems that can be used long-term, including schools, medical facilities, secure shelters, agricultural support, wells and water distribution services, waste management services, etc. Efforts are being made for relocation for families in the most vulnerable areas as well to avoid potential natural disasters. From what I’ve researched, the emergency and basic needs of food, water, shelter are of course being given priority and many accomplishments have been made since the 2017 exodus began, but conditions are not adequate and safe for all families. There are strides being made to improve upon the circumstances and create preventative measures by aid organizations working together to assess the most vulnerable areas of the community and track resource allocation. It may sound weird, but to implement effective distribution services there needs to be a track of what families reside in the community and the resources given to them. Particularly at this time when the amount of aid resources isn’t sufficient to care for everyone in Cox’s Bazar at once. This reminded me of our class discussion last week where I mentioned that questionnaires, which are used to determine who gets help first and how much, make me uncomfortable and sad because it is a way of quantifying people’s pain and who are we to do that? But, when resources are limited and fair distribution cannot be guaranteed, how can we not? I do appreciate that efforts to minimize dependency are being made in Cox’s Bazar by teaching the Rohingya agriculture skills and promoting education. I think this is a great way to work toward self-sufficiency, but I just wish in the meantime we could avoid these parameters that give levels to people’s suffering, however, I think that may be impossible with circumstances like these.

Works Cited

Bangladesh. UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency Operational Update. Jan 2019. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/67736. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Humanitarian Crisis Management Programme: Bangladesh Cox’s Bazar. BRAC. 20 Nov 2018. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/HCMP-monthly-update-_-20-November-2018_optimized.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Hunt, Katie. “Rohingya Crisis: How We Got Here.” CNN. 12 Nov 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/12/asia/rohingya-crisis-timeline/index.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Hunt, Katie. “Rohingya Crisis: ‘It’s Not Genocide,’ Say Myanmar’s Hardline Monks.” CNN. 25 Nov 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/25/asia/myanmar-buddhist-nationalism-mabatha/index.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

JRP For Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis. OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2018. https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/JRP%20for%20Rohingya%20Humanitarian%20Crisis%202018.PDF. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

“Myanmar Rohingya: What You Need to Know About The Crisis.” BBC News. 24 April 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41566561. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Nichols, Michelle. “China Fails to Stop U.N. Security Council Myanmar Briefing.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-un/china-fails-to-stop-un-security-council-myanmar-briefing-idUSKCN1MY2QU. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

“Rohingya Refugee Crisis in Bangladesh.” Action Against Hunger. 2 Oct 2017. https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/story/rohingya-refugee-crisis-bangladesh. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

“The 5 Things We’ve Found After One Million Consultations in Cox’s Bazar.” Medecins Sans Frontieres. 5 Feb 2019. https://www.msf.org/weve-provided-one-million-consultations-coxs-bazar-5-things-weve-found-bangladesh-rohingya. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Wong, Edward. “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Myanmar Military Over Rohingya Atrocities.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/17/us/politics/myanmar-sanctions-rohingya.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

(Humanitarian Crisis Management)

(Humanitarian Crisis Management)