Humanitarian response report

Prompt

For this assignment you are to choose one of the humanitarian crises around the globe and report how the humanitarian sector is responding to the needs of the affected communities. To the extent possible try to go beyond mere description of the crisis and transition to analysis using some of the insights you have learned from our texts and class discussions. Your humanitarian response report should address at least the following questions:

- What is the history of the situation?

- What precipitated the crisis?

- What is the current state of this humanitarian crisis?

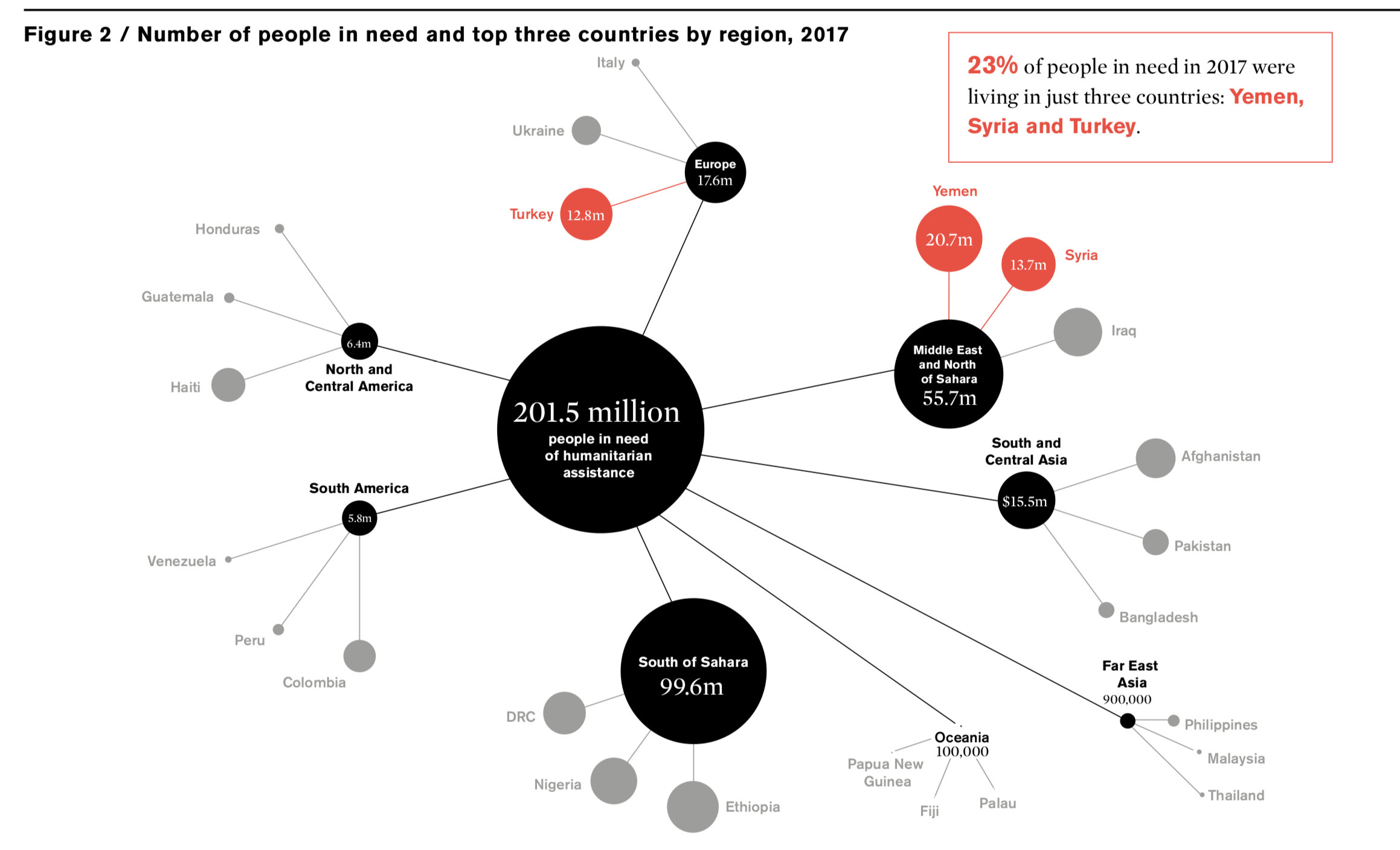

- How can you describe the need in the affected communities and the response in numbers?

- What governments are involved?

- How has the US press/media covered this story? How has the global press covered the story?

- What major INGO’s are responding?

- What CBOs, local religious groups, and governments are responding?

- How are major needs identified and responses coordinated?

- How are safety issues managed at refugee camps and/or distribution points, clinics, and other venues where the affected community interact with aid workers, especially regarding proactive policies and procedures dealing with SEA/GBV?

- To what degree are needs being met?

- Who makes up the staff implementing the humanitarian response?

Rubric:

- Due by class meeting time, Monday, February 25.

- Late posts will be downgraded at least one letter grade.

- Comments to at least three colleague’s posts by February 26th by 10:00PM EST.

- At least four citations: at least one from text and/or other assigned reading, at least two from outside academic sources, and one citation of class lecture/discussion. Note: you are to read/watch/listen to all of the material in the hyperlinks in the parent post above; your contact with the material should be apparent in your post. Reference class lecture/discussion is this form (SOC371:3-27) i.e., course number and date.

- List references at the bottom of the page (MLA format).

- At least one photo and/or video link appropriate to and enhancing the content of your post.

- Minimum 0f 700 words (excluding references).

- Grade will be based on quality and quantity of response to the post prompt including adherence to the above benchmarks.

- Keep in mind that you are writing for a broad audience that is educated and interested in this topic; infuse your post with the sociology you are learning/have learned in a non-jargonistic manner

As a shorthand for the longer, more detailed grading rubric above this SOC summary may be useful.

- S = demonstration of understanding and application of sociological concepts, theories, etc. germane to the topic, especially those taking about in the text and in class

- O = organization and structure overall; flow of ideas, appropriate and contextualized use of images and videos, proper documentation of sources

- C = analytical creativity; going beyond obvious restatement or simple examples and pushing boundaries of thought and perspective; finding outside academic sources beyond the obvious

Please check Assignments/Assignment 4 before you Publish.