Honduras lies in the heart of the “Northern Triangle”, bordered by El Salvador and Guatemala. Rocio Cara Labrador, a writer for the Council on Foreign Relations, explains that these countries, “were rocked by civil wars in the 1980s, leaving a legacy of violence and fragile institutions. The region remains menaced by corruption, drug trafficking, and gang violence despite tough police and judicial reforms.” The current humanitarian crisis in Honduras is a direct product of its weak political system. Although unstable since the 1980s it was the 2009 constitutional crisis which completely dismantled any sense of structure left in the country. An attempt to change the Honduran constitution, led by President Mandela Zelaya, culminated in his removal from office and exile to Costa Rica. The coup d’état was carried out by the Honduran military on orders from their supreme court. The United Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS), and the European Union, and the Obama Administration condemned the removal of Zelaya as a military coup and all ambassadors left the country. On 5 July 2009, all member states of the OAS voted by acclamation to suspend Honduras from the organization.

Hundreds of protests followed the coup and the country was left without leadership. Any ambassadors or other foreign officials unable to flee were detained and beaten by Honduran troops. All those associated with Zelaya (politically or otherwise) were also taken into custody. In January of 2014, Juan Orlando Hernandez assumes the role as the next national president. This new leadership caused hundreds more riots and protests by the Honduran public. These demonstrations led at to increased police involvement (from an incredibly corrupt national department) and military violence soon became the most terrifying threat for the country. Prisons became vastly overcrowded, and administration lacked the resources to properly provide for inmates. In response to this brutality, organized crime escalated. Some of the most notorious groups (including Mara Salvatrucha and the Mara Dieciocho gangs) came to truce agreements, in attempts to reorient their efforts.

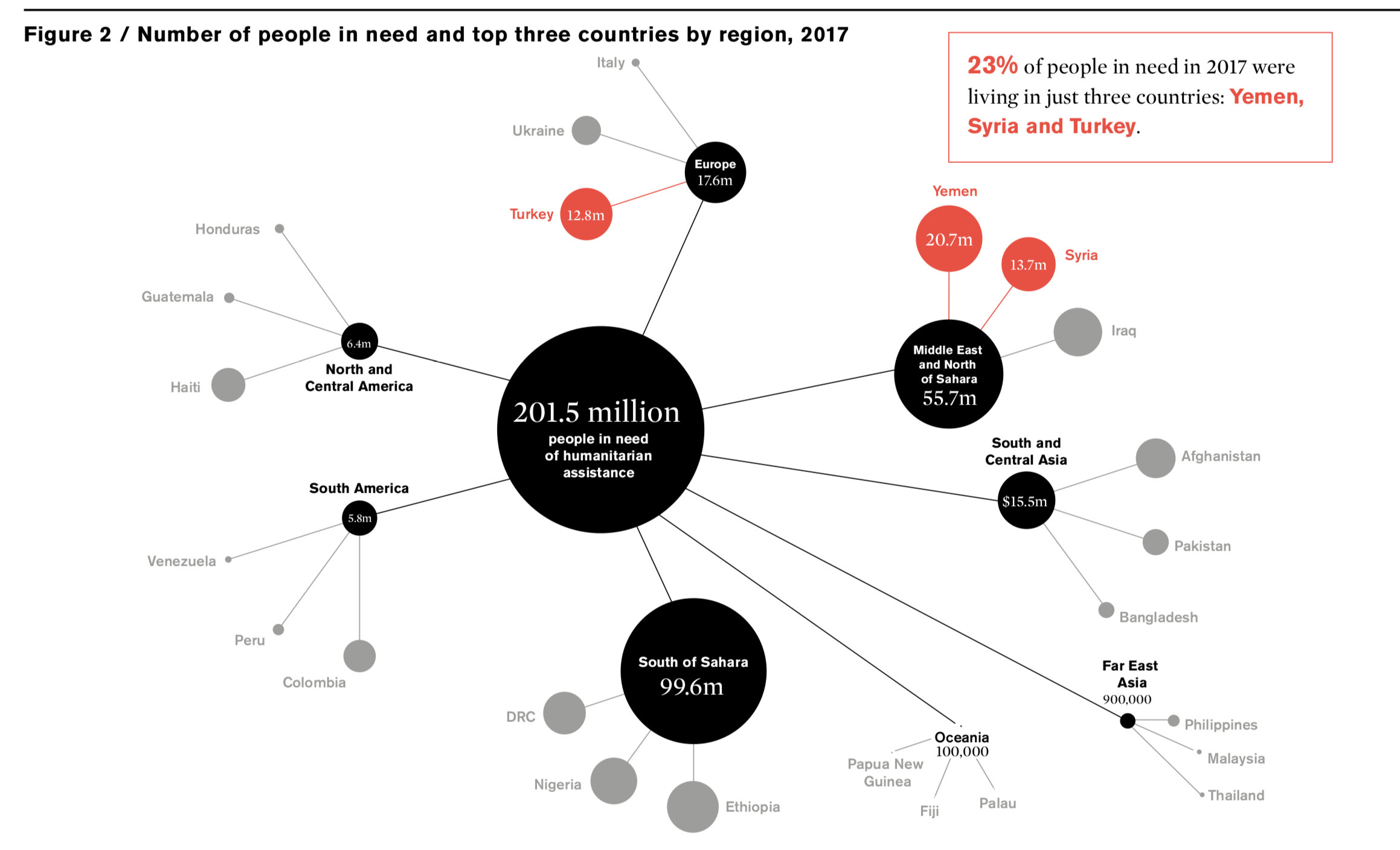

As the situation worsened and a humanitarian crisis comparable to that of Syria developed on top of political turmoil, foreign involvement weakened. Honduras was growing to become one of the most dangerous countries in the world, and it was in the immediate interest of aid organizations and political affiliates to make sure their assets were safely out of harms way. Peace Corps had 150 volunteers placed in the country, all of which were removed. USAID continued to provide monetary assistance, other organizations including the World Bank suspended foreign aid. Many countries blocked travel to/from Honduras, and as terror rose within its borders, people began to flee.

The Honduran supreme court then called for a “media blackout” blinding the outside world from what was happening within the countries borders. Anyone left inside, especially reporters were put at extreme risk. “At least 62 journalists have been killed in the country between 2006 and 2017, according to data from the Commission for Investigation of Attacks on Journalists of the Latin American Federation of Journalists.”

The current state of Honduras is weak, and their history of unrest has caused the recent “Caravan Crisis”. Fleeing persecution, poverty, and violence thousands of migrants traveled to Mexico from the Northern Triangle. With open intentions of seeking refuge in America, the “caravan” reached the US-Mexico border late last fall. President Donald Trump has labeled the migration as an “invasion” and tweeted dozens of times about his distrust and dislike for the people of Central America.

There is a long history of U.S. interventionism and involvement in Honduras. Marysol Fernandez, writer for The Brown Daily Herald, states that “More recently, Honduras has become one of the United States’ strongest allies in Central America, especially in the face of left-wing successes in neighboring countries like Guatemala and El Salvador.” Yet in light of the migrant crisis, Trump has first blamed and now threatened the Honduran Government with tweets such as, “The United States has strongly informed the President of Honduras that if the large Caravan of people heading to the U.S. is not stopped and brought back to Honduras, no more money or aid will be given to Honduras, effectively immediately!”

There have been two clusters of responses to this, both in agreement that the Trump administration has contributed to situation in Honduras. The Center for Immigration Studies released a statement saying that, “In the Northern Triangle we have proposed to work together with the United States and Mexico in the Alliance for Prosperity Plan to create the necessary conditions in the countries so that these people do not make the decision to [emigrate] to the United States.” Rights activist, Dunia Montya claims that, “the Trump government validated an illegitimate Honduran government, and is therefore partially responsible.” Some people believe that the US has no right to remove aid or refuse refugees because of their history with the country. Others believe that by removing US involvement, Honduras will be better able to grow- blaming the United States influence for many of the structural issues.

After the removal of most other political associates, international help has not been quick to return. Because they are not at arms internationally, Honduras has maintained very docile relationships with other countries. No one seems interested in coming to help, thus prompting the citizens to flee. El Salvador has maintained normal trade relations and is seen by many as a co-nation to Honduras. Guatemala has similarly maintained trade relations but is more often expected to cause border tension. The biggest threats to Honduras are not their neighbors but rather their own short-comings.

Human Rights World Report explain, “Efforts to reform the institutions responsible for providing public security have made little progress. Marred by corruption and abuse, the judiciary and police remain largely ineffective. Impunity for crime and human rights abuses is the norm.” Gang violence, drug wars and extortion remain commonplace and the country is notorious for having the world’s highest murder rate per capita. “Extortion is also rampant. A 2015 investigation by Honduran newspaper La Prensa found that Salvadorans and Hondurans pay an estimated $390 million, $200 million, and $61 million, respectively, in annual extortion fees to organized crime groups.” So, the question must be asked, where is the greatest need and how can it be provided?

A refugee crisis is defined as “large groups of displaced people, who are afraid or unable to return to their homeland. With the implication that a group of individuals is subject to persecution, war and/or systemic violence.” So, when considering where to provide aid, one should first determine the specific reasons that refugees became such. The Borgen Project, is a nonprofit organization addressing world poverty and hunger, with a specific interest in the Honduras crisis. Their research teams concluded that the best way to disrupt the degenerate structures ruling Honduras, include targeting youth so as to make a generational difference. They recommend doing so through food service, and education and literacy programs.

“One method for how to help Honduras is by donating and/or serving with Food for the Poor (FFP), an international relief and development organization based in the United States.

Another option, standing for Health, Education and Literacy Program, HELP Honduras works to supply students with uniforms, books and school supplies in order to support their education and keep withdrawal rates down.”

There aren’t many actual INGO’s working in the triangle (largely due to the degree of violence as mentioned above). Humanitarian groups (religious, local, etc.) that are involved include:

- Bay Island Conservation Association

- Guaruma

- Bilingual Education for C.A.

- Honduras Children

- Helping Honduras Kids

- Pier Roatan

- Utila Community Clinic

- Un Mundo

- El Techo Para Mi Pais

Unforunately without more funding, the Honduras crisis can be expected to continue. Their issues are deep rooted and it will be difficult -if even possible- to break through the corruption. The migrant caravan has been labeled a “threat” by President Trump and will likely lead to history-making American involvement, as we decide how to move forward. I think it will be imperative to continue researching the problems within the country, to help avoid future mass migrations, and strengthen the Honduran political system to some level of stability. The attached video provides a similar narrative to that above concerning the US response to the migrant caravan. It includes footage of the refugees as well as statements from the President. Although a democratic press release, I think it’s important to have some images to associate with the story.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cnbJT15SVNQ

Baker-Jordan @skylarjordan, Skylar. “The Migrant Caravan in the US’s Fault – Trump Has to Let Them In.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 26 Oct. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/voices/trump-migrant-caravan-where-mexico-honduras-guatemala-central-america-a8597741.html.

Borgen , Clint. “About Us.” The Borgen Project, 2019, borgenproject.org/about-us/.

Cabera, Jorge. “World Report 2018: Rights Trends in Honduras.” Human Rights Watch, Reuters, 18 Jan. 2018, www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/honduras.

Cuffe, Sandra. “Migrant Caravan Activists: Trump to Blame for Honduras Situation.” GCC News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 16 Oct. 2018, www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/10/migrant-caravan-activists-trump-blame-honduras-situation-181016213544549.html.

Fernandez, Marysol. “Fernández ’21: America’s Role in Honduras’ Democratic Crisis.” Brown Daily Herald, 5 Dec. 2017, www.browndailyherald.com/2017/12/05/fernandez-21-americas-role-honduras-democratic-crisis/.

“How to Help Honduras and Keep Its Citizens Safe.” The Borgen Project, 19 Dec. 2017, borgenproject.org/how-to-help-honduras-and-keep-its-citizens-safe/.

Labrador, Rocio. “Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 26 June 2018, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle.

Lind, Dara. “Trump’s Latest Tweets about the Migrant Caravan, Explained (and Debunked).” Vox.com, Vox Media, 18 Oct. 2018, www.vox.com/2018/10/18/17994508/migrant-caravan-honduras-trump-tweet.

Lunka , Kausha. “Honduras Responds to U.S.-Bound Caravan.” CIS.org, Center for Immigration Studies, 4 Apr. 2018, cis.org/Luna/Honduras-Responds-USBound-Caravan.

Nevins, Joseph. “How US Policy in Honduras Set the Stage for Today’s Migration.” The Conversation, The Conversation, 4 Jan. 2019, theconversation.com/how-us-policy-in-honduras-set-the-stage-for-todays-migration-65935.

Pike, John. “Military.” Texas Revolution, Global Security , 2018, www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/centam/sv-forrel.htm.

Staff. “Honduras Profile – Timeline.” BBC News, BBC, 16 May 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-18974519.

staff. “Honduras.” The NGO List, Weebly, 2018, www.thengolist.com/honduras.html.

Staff. “Migrant Caravan: What Is It and Why Does It Matter?” BBC News, BBC, 26 Nov. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45951782.

“World Report 2018: Rights Trends in Honduras.” Human Rights Watch, 18 Jan. 2018, www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/honduras.

(Humanitarian Crisis Management)

(Humanitarian Crisis Management)