Are we all global citizens? Prior to this class I would have answered yes, that if each in everyone of us interacts in the global economy, and stays informed by the news every so often, then we are indeed. However, this course has introduced me to the possibility that not every person is a global citizen, that the term is more complex. Everyday people are interacting with society on a global level, even when we cannot see it occuring. By purchasing a products in a local store, whose products may be produced in a country across the world, or by having casual interactions with others outside of the United States through social media, we are habitually engaging with the world on a global scale, it is globalization. Although, I begin to understand the point where being a citizen in a globalized world, does not entail that one is a global citizen. After doing more research on indicators of a global citizen, I have become aware of the term an exemplary global citizen, these are individuals who do a large amount of philanthropy, such as Emma Watson, or Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan.

These individuals all have positive initiatives to combat social issues, through raising awareness and funds for education, health, and women’s rights. However, it is not only acclaimed citizens who can be exemplary global citizens. Hugh Evans, does a Ted Talk about defining a global citizen, and talks about his life story and how he as a child embarked on the journey to becoming a global citizen, (https://www.ted.com/talks/hugh_evans_what_does_it_mean_to_be_a_citizen_of_the_w orld?language=en#t-55687). Hugh’s experience in the Philippines, sleeping next to spiders on the floor at night, piqued his curiosity and devotion to understanding this poverty, and began to make an effort toward a thorough understanding. Hugh’s life story goes to show that people can make efforts to change the world on a global scale by caring about the communities aside from their own, such as a place in which they have traveled, or gone to school in. In high school I had traveled to Nicaragua on a service trip, and in return I had a life changing experience from engagement with the community. Experiencing the poor living situations, and daily hardships in Nicaragua has led me to deepen my involvement in service, which has led me to joining the Habitat for Humanity club at Elon, where I am continuing to shape myself into the global citizen I would like to become.

To be a global citizen, people must to some degree live in consensus with humanitarianism, which is referred to as a way of living. The people who participate in this lifestyle are truly compassionate and revolve their activities around saving lives and providing aid to those in difficult situations (What is Humanitarianism?). Humanitarian efforts have been a controversial topic, specifically in the aid sector. By taking a look at In the Eyes of Others, a novel that looks at the humanitarian aid system from the perspective of beneficiaries, the space for ethical issues has been brought to my attention. This space is quite uncomfortable as it is often overlooked by the humanitarian aid workers who are entering and providing help to countries where adequate systems such as health systems are nonexistent. However there is huge risk with these humanitarian efforts because the issues they are solving are temporary issues at hand, and they are not delving deep enough into the concern that sparked the poor health.

The terms, global citizen and humanitarianism are coexisting. A global citizen is, in simple terms, one who is involved in activities that directly promote the wellbeing of societies who are in need of aid. Inversely, humanitarianism is a way of living, that involves giving which stemmed from the global citizens, those who have a compassion to end the suffering they have witnessed worldwide.

Despite the positive efforts imposed by global citizens who are following their compassion to better the situations of societies facing hardships, there are many critiques on whether humanitarian aid is being imposed efficiently. Below are two quotes from people who have commented on the humanitarian aid system.

- “…until we recognize how dependent we are on the oppression and marginalization of others for our own betterment and benefit (i.e. access to cheap disposable goods, foreign foods and fresh imports, temporary foreign workers to fill low-income job vacancies, etc…), humanitarian aid work is just another cog in this bullshit machinery.”

- “We [aid workers] are band-aids born of affluent guilt and survive almost entirely on the donated profits of unjust privilege and power.”

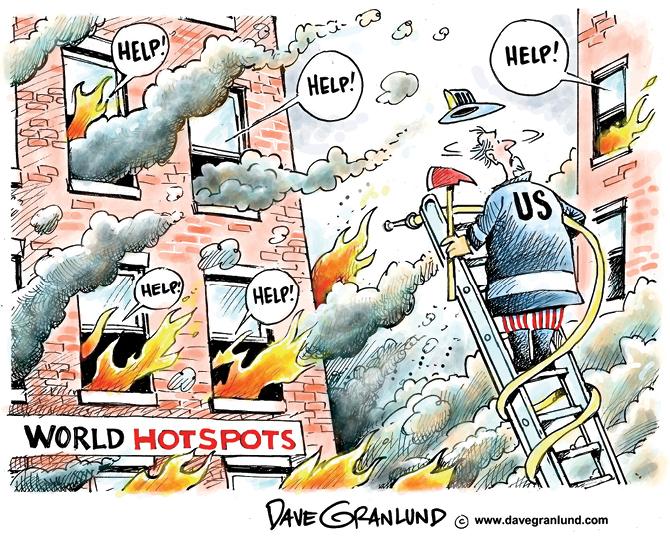

Both of these comments shed a negative light on humanitarian aid, which opens up a door to discuss whether or not the acts of aid workers are truly benefitting the core issues of a country or are for personal welfare. Several times aid workers have traveled to countries where there are starving children, nonexistent education systems, and poor healthcare systems. They try to combat the issues at hand, and then leave when they see that their work has been done. Although, it is not the visible issues that is the core problem, those are solely the effects of the core problem which generally lays within the unjust political system.

So, my take on this, is that aid workers do have a compassionate persona, and want to fix the visible situations of the people in such underprivileged countries, but their work is almost a tease as they do not work to tackle the deeper issue. I would agree with the second quote that, aid workers are simply band-aids, they repair the visible damage of the needy people however their work is not effective in the long term as the core issue, the corrupt political system continues to thrive. The power and privilege that the aid workers have to alleviate the poor conditions of others, should be used in a more efficient manner by possibly building a sector that will devote their time to search for the core problem causing the society such hardship. Possibly, the problem is that the system of humanitarian aid is incapable or without the power to solve the deeper issues of other countries, and is a job that should be left to government officials to deal with.

The main theoretical perspectives in sociology are general ways of understanding social reality, including functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism and feminism. Gaining knowledge on the major theoretical perspectives has helped me to better understand and accept the perspectives from the two commentators above by comparing their words to the main points of each theory. Specifically, the conflict theory has helped me to understand the perspective more clearly of the first commentator. This theory involves the game theory term; zero sum, in which one person wins, and the other loses. The term is relevant here because commentator one discusses how the aid workers are the winners, when I would have thought it was the aid receivers winning. This theory allows me to see the perspective that even though the aid workers are giving and supplying the less fortunate with aid, at the end of the day the workers will return to their developed countries and engage in the global economy. With the globalization occurring today, developed countries often take advantage of the underprivileged countries for access to cheaper products and production means. So, in sum, it is crucial to realize that there are different perspectives people have on controversial topics, and they can enlighten us to think outside of the box and perhaps tackle an issue in a way we haven’t thought of prior.

To conclude I wanted to leave a quote from the Ted Talk I included above, to continue thinking about the term global citizen:

“Of a total population who cares about global issues, only 18 percent have done anything about it.”

Sources:

What Is Humanitarianism? Raptim Servivces. https://www.raptim.org/what-is-humanitarianism/

Cole, Teju. “The White-Savior Industrial Complex.” The Atlantic, 21 Mar. 2012.

Evans, Hugh. “What Does it Mean to be a Citizen of the World?” https://www.ted.com/tal ks/hugh_evans_what_does_it_mean_to_be_a_citizen_of_the_world. TedTalk. 2016.