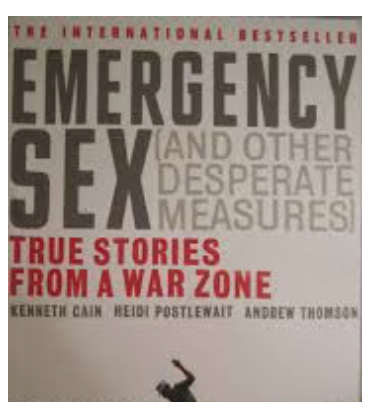

First off, Emergency Sex, has the most kick-ass title of any book I’ve ever been assigned in a class. It’s also not at all what the book is about. Its full title, Emergency Sex (And Other Desperate Measures): True Stories From a War Zone, by Kenneth Cain, Heidi Postlewait and Andrew Thomson, gives a better idea of stories the three authors tell in this memoir of humanitarian aid workers who join the United Nations with a dream making a difference. By weaving together their stories and perceptions of the time they spent as aid workers, the authors create a narrative of their friendship, the aid community, the challenges faced by war torn and developing countries and a heavy dose of personal stories about the relief they found in partying, drinking, and often – sex with pretty much whoever was available.

The book is set in the 1990’s, a time of enormous problems across the world. The three authors stories’ merge in Cambodia where they work to ensure the first free election since the end of the Vietnam war. Their lives and work continue to intersect in Somalia, Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia and Liberia. The book examines the personal lives of the aid workers, the successes and failures of the United Nations, and the complex global issues that face humanitarian workers as they struggle to make a difference in the lives of people in developing countries.

While each of the characters is changed enormously by their experiences working as foreign aid workers, Heidi, a social worker from New York, makes the biggest transformation. When the book begins she is a spoiled self involved, woman married to a modeling agent. She determines she is bored with her life and seeks something else, but she is not really sure what. Her journey to becoming a passionate aid worker begins in the secretarial pool at the United Nations. She comes off as a bit shallow and her initial reason for going to work in Cambodia has nothing to do with making life better for the people in that nation; she simply wants the extra combat pay that comes with the job. Over the course of the book, she is transformed into a committed global citizen who can’t see herself ever again living in the comfort of the United States.

While I think both of the male authors are more interesting, intellectual and complicated people, I would still choose to meet Heidi if given the chance. Her experience in the field was always colored by the fact that she is a woman, and as I consider the possibility of humanitarian aid work for myself, I would like to hear more about what it is like from a woman’s perspective.

At the start of her time in Cambodia, Heidi is utterly uninterested in Cambodia or her work. After complaining about her difficult boss she says, “this time I don’t care. I’m here for six months to make money and then she can fuck off.” (Cain, Postlewait, Thomson 50). But very quickly as she sees the difference this work makes in people’s lives, she becomes more and more committed to the work. On the day of the Cambodian Election, for example, she writes, “I find their presence moving.” And adds, “My own problems suddenly seem amazingly inconsequential.” (Cain, Postlewait, Thomson 82) As Heidi becomes more immersed in the cultures of the countries where she works, she becomes a truly passionate and committed humanitarian aid worker.

Heidi’s moral career is clearly demonstrated as she makes her personal journey throughout this book. Sociologist Erving Goffman defines a moral career as “…any social strand of any person’s course through life…the regular sequence of changes that career entails in the person’s self and in his imagery for judging himself and others.” He goes on to say, “Each moral career, and behind this, each self, occurs within the confines of an institutional system…” (Goffman 168)

From the very beginning, Heidi is constantly assessing and measuring herself through the eyes of others. Whether fleeing in embarrassment when she chooses the wrong outfit for her husband’s office party, or fearing she will be seen as intellectually inadequate by her potential new roommates in Cambodia, Heidi defines herself by allowing those around her to function as a mirror. But, while she doesn’t yet know who or what she wants to be at the beginning of the book, Heidi recognizes that she is influenced in the wrong way by her surroundings with her husband in New York, and so she seeks a new life. As she makes her journey through war zones in the developing world, Heidi undergoes a transformation in her moral career just as she undergoes changes in her actual career.

By the end of the book, Heidi has lost lovers, husbands, and friends and has seen untold horrors in each of the countries where she worked. As she struggles with grief she realizes what she needs is a purpose, “something to force me out of bed each day. I need to go back to work.” (Cain, Postlewait, Thomson 282)