Local aid workers

Dealing with nomenclature when discussing the aid and development sector can be both a challenge and an opportunity, and this is clearly the case when talking about ‘local aid workers’ as I have done in my last several posts. Certainly domestic (in this case within the United States) workers like Jennifer Foy and Marlene Myers fall within a very broad definition of ‘local aid worker’, but these women fall outside the more classic (stereotypical?) image of local aid workers that, for example, made the news recently in Afghanistan.

By some estimates, local aid and development workers outnumber expat aid workers by a ratio of as much as 10 to 1, with one US based aid and development NGO of which I am aware reporting only 5% of their international staff as expats.

Here is a statement from an OCHA report, “National aid workers constitute the majority of aid staff in the field – upwards of 90 per cent for most international NGOs – and undertake the bulk of the work in assisting beneficiary populations.”

Local workers are, in the most literal sense of the word, essential for the delivery of aid in much of the world, and the recent deaths of  6 local International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) aid workers in Afghanistan underline how dangerous their jobs can be.

6 local International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) aid workers in Afghanistan underline how dangerous their jobs can be.

Western centric methodology

Although it is an open question as to what the best methodology for hearing the voices of local aid and development workers might be, I am certain that there is no ‘one size fits all’ answer.

The age-old tradeoff is between more in depth and time intensive ethnographically oriented approaches with inherently limited generalizability and the quicker, more comprehensive survey technique. Within the survey technique there are wide array of tools going from the time intensive but data-rich door to door and/or face to face interviews all the way to the more technology dependent online survey. The advantage of the former is rich data, the downside is that it is very time/human resource intensive and, since many ears can be listening during an interview, the respondents may be compromised in what they say. The advantage of the online survey technique is ease and speed, but access to all respondents because of limited access to technology, translation complications, trust, and security issues will inevitably into play.

Inherent in all of the approaches is the hoary ‘GIGO’ warning, namely, garbage in, garbage out: ask a stupid question and you’ll get a stupid answer. But what are the right questions in each specific setting?

One colleague I know has been doing ethnographic and extensive face to face interviews of local aid workers in Kenya, and this method allows for very rich data. One massive hurdle for both face to face interviews and online surveys -any methodology for that matter- is language differences and the attendant translation issues. I had that lesson presented to me very clearly when I worked to get Arabic, French and Spanish versions of the online survey the data from which is the basis for Aid Worker Voices. All three translators pointed out numerous phrases and words that just could not be translated and/or had embedded cultural assumptions. Of note is that Caroline Abu-Sada and other researchers in In The Eyes of Others (click the link for the book in pdf: msf-in-the-eyes-of-others) talked about similar translation issues when doing their work for MSF.

But now to the preliminary results referred to in the title to this post….

A Zambian development worker since 2009

I have known and worked with Mr. Voster Tembo, a Zambian development worker, for many years. We have worked on several projects, the most significant of which was the founding of the Zambian Development Support Foundation in 2013. Yes, I know about the pitfalls of MONGO’s, but this one is different (isn’t that what they all say?) and

intended to be scaleable. But details on that can wait for another post.

intended to be scaleable. But details on that can wait for another post.

My most recent collaboration with Voster is an attempt to address one failing of the survey of aid and development workers that my colleague J (aka Evil Genius) and I launched nearly three years ago. That survey reached over 1000 self-identified aid and development workers, but only 5% identified as ‘local aid workers’ hence we heard and reported on a very skewed, and likely Western centric set of voices.

Voster and I talked about these results and agreed that the voices of local workers needed to be heard. After discussion with some of his colleagues we constructed a short online survey intended to be an exploratory study that might lead us to both better questions and to finding efficient ways to gather data. The best first step would have been to do extensive interviews of a number of development workers and learn from them which questions were relevant and seek their counsel as to how to get more voices gathered. Given time and resource limitations we decided that an exploratory study seemed an acceptable second choice.

Background regarding the survey

The population we intended to reach were Zambian ngo/aid workers who regularly interact with visiting mzungus (either individually or in groups), with the overall goal to get 100+ responses within 30 days. Our purpose was to understand how visiting mzungus are seen by those who work with them with the ultimate goal being to better facilitate and enhance inter and intra group communication, coordination and cooperation. A secondary goal was to do preliminary work toward the establishment a useful typology of mzungu visitors, with descriptions of each category type that might lead to refinement of a typology and eventually provide data for analysis and explanation that would be useful in establishing enhanced interaction protocols for both muzungu groups and those who work with them.

Examples of settings where Zambians would interact regularly with outsiders include INGO based home building teams coming from primarily the US, western Europe and the UK, staff of international development NGO’s, USAID staff, Peace Corp volunteers, and so on.

After the short survey was constructed and made live online, we used social networking to get the word out about the survey. For a variety of reasons the response has been anemic, with only 20 respondents.

Through our eyes: views of Zambian (and other African) aid and development workers

Given the small and markedly limited sample, the results are at best preliminary. With that stated, here are some highlights.

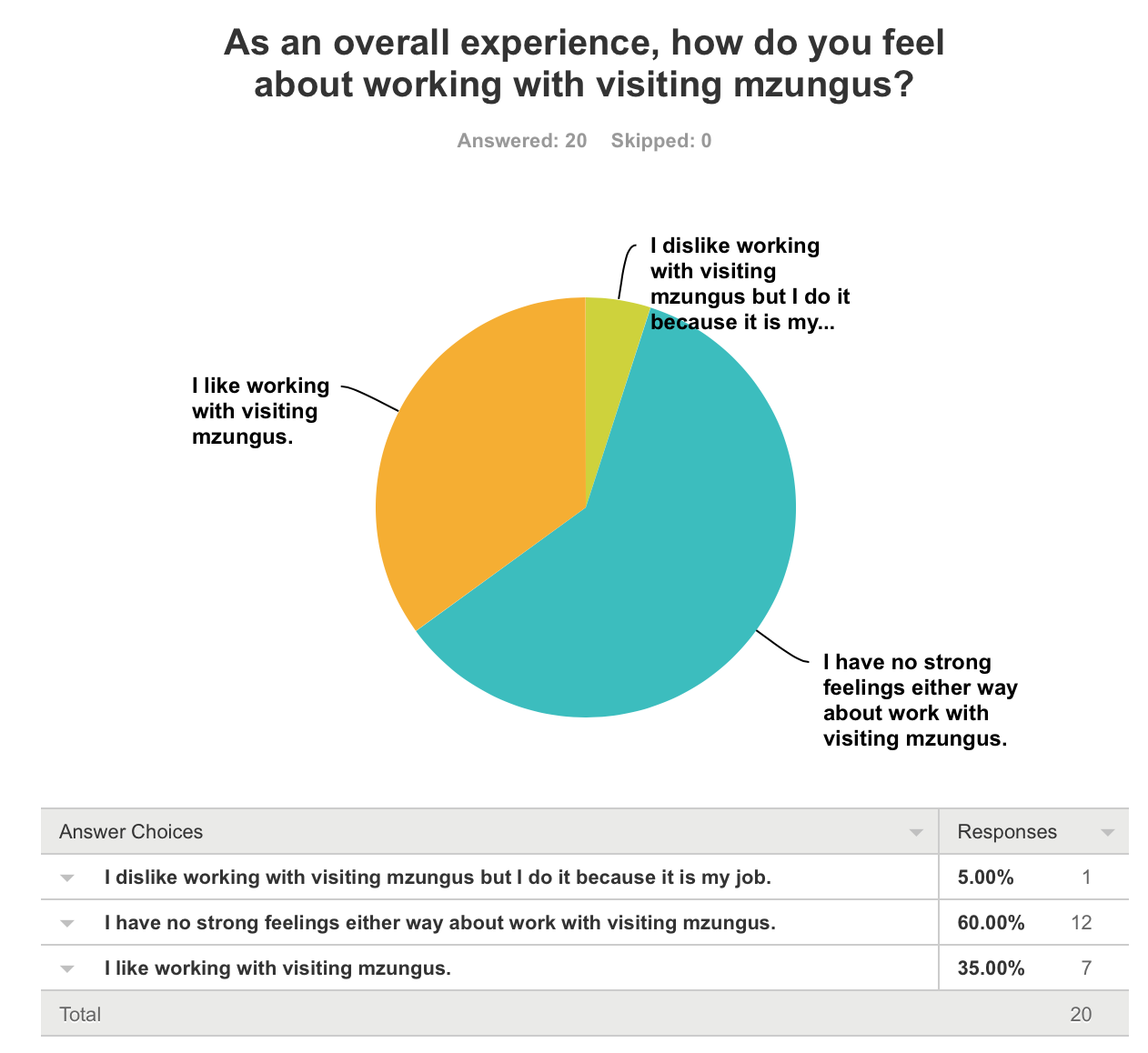

The responses to the first question (Q1) indicate a markedly positive attitude toward working with mzungus. Q2 asked the respondent to expand on their answer and all 20 respondents offered some insights.

The responses to the first question (Q1) indicate a markedly positive attitude toward working with mzungus. Q2 asked the respondent to expand on their answer and all 20 respondents offered some insights.

The positive comments were many, perhaps best presented in this one respondent’s words,

“I like working with Mzungus as there are more benefits attached to the working relationships: 1) cultural learning from each other in a global environment. 2) platform for sharing knowledge on best practices on the core business e.g housing delivery models. 3) Resource mobilisation- by this I mean they are able to link or bridget up opportunities for development between their country of origin and the country hosting them. The current scenario is they are from developed countries and the housing country is still developing. 4) They bring in innovations on issues bordering on socio- economic activities for improved living of the target groups.”

A few other positive comments were,

- “Most of them show eagerness to learn about Zambia and how we do things and I get great satisfaction in talking about my country and the many strengths as well as weaknesses and challenges that we have.”

- [They] show openness and most are willing to learn but also to learn about the countries where they are coming from is really fulfilling in working with them.

- “When we work and eat together like a family that gives more pleasure.”

These next two comments are from respondents who indicated “I have no strong feelings either way about work with visiting mzungus”,

- “I am neutral to anyone I work with, I am just careful working with strangers. Generally, whites are more exposed so I am always eager to learn from them, and to me they have been helpful.”

- “I have no strong feelings either way because they come in different shades. Some of them come in as professionals who know what they ought to do while some come in as ‘apprenticees’ who are learning there work but behave like they know.”

And these next two speak to the a sore spot,

- “I don’t really say I don’t like them, I can work with them but most of the time they think they are more superior than Africans.”

- “There are some that make you feel inferior.”

The remainder of the short survey asked questions continuing the focus on working with non-Zambians, several asking about which categories of mingus were harder to work with, males or females, older or younger. These data indicated that those two variables were a wash, no real pattern differences could be identified.

The remainder of the short survey asked questions continuing the focus on working with non-Zambians, several asking about which categories of mingus were harder to work with, males or females, older or younger. These data indicated that those two variables were a wash, no real pattern differences could be identified.

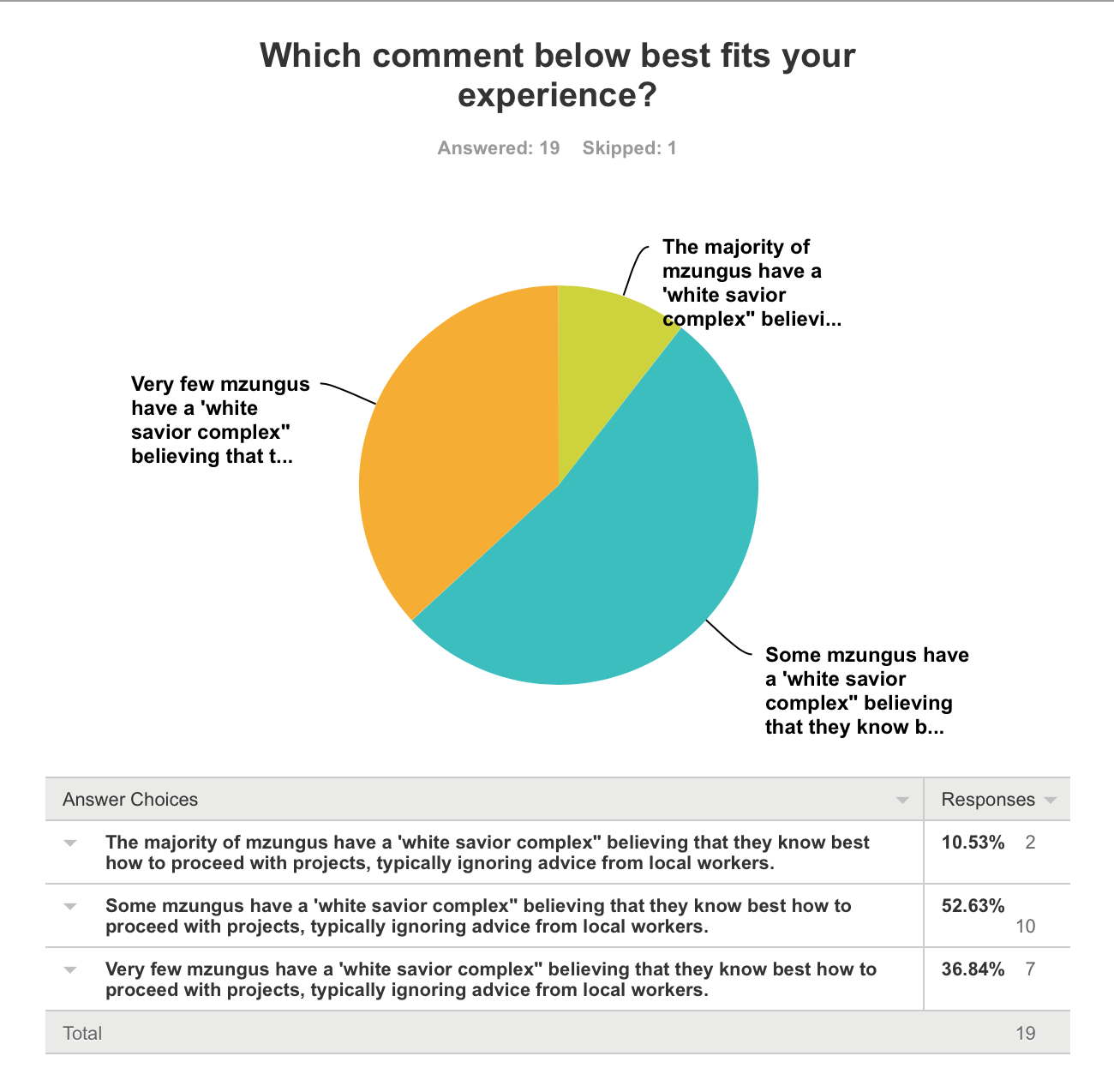

After considering the cross-cultural cache of the phrase “white savior complex” we posed a question with that in mind. Here are a few statements from respondents that extend these data and provide some suggestions.

- “Whites who volunteer with NGO’s are different generally from those who come to Africa for commercial business. Those with NGO’s are more open but with a subjective perception of the continent, yet those in the business world, here for profit are objective and even corny.”

- “The muzungu should take time to learn the local environment and then work. And there is no need to bring in a muzingu expat when there are indigenous people with the same skills and qualifications.”

- “They should not come with pre-concieved minds and should know that blacks/Zambians have their own strengths that can add value to any project/intervention.”

- “It is important to engage the locals in the planning and implementation of projects unlike just imposing. Most take funding of the project to be owners of the projects.”

A close reading of the above suggestions, I think, gives a local Zambian voice to some of the discussions and debates I have seen throughout the blogosphere related to local aid workers.

Moving forward with this project?

Our exploratory online survey attempting to reach local aid and development workers in Zambia has been minimally effective. I am just now off a Skype conversation with Voster and we agreed to continue exploring and critiquing not only the methodology but as well the many assumptions and intentions that underlie this research. Our question choices were intended to be relevant and interesting, but we are not convinced that goal was reached.

We do remain convinced that these local Zambian aid and development worker voices need to be heard.

Post Script

My research on local aid workers began decades ago in 1994 when I piloted a new technique for doing survey research. My study was on the self esteem of the Village Health Workers at the Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) in Jamkhed, India. This research technique may still be of use in some instances; click here to read: the-likert-scale-goes-marathi and let me know if you have any questions or feedback.

Please contact me if you have any comments, questions or suggestions.

Follow

Follow