Survivor: a book review

Getting my hands on Survivor

Getting my hands on Survivor

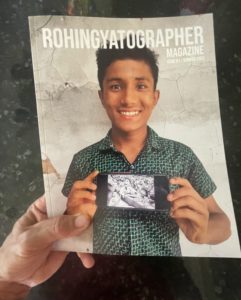

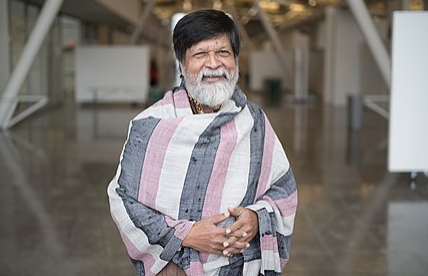

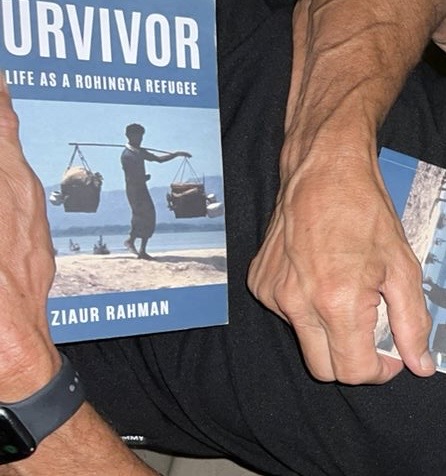

This past August I was able to secure several copies of Ziaur Rahman’s stunning memoir Survivor: My Life as A Rohingya Refugee. I had gotten to know Ziaur two years ago through numerous online conversations and was honored to be among the many who assisted him in the process of getting his story published. Holding the book in my hands for the first time felt like a dream coming true.

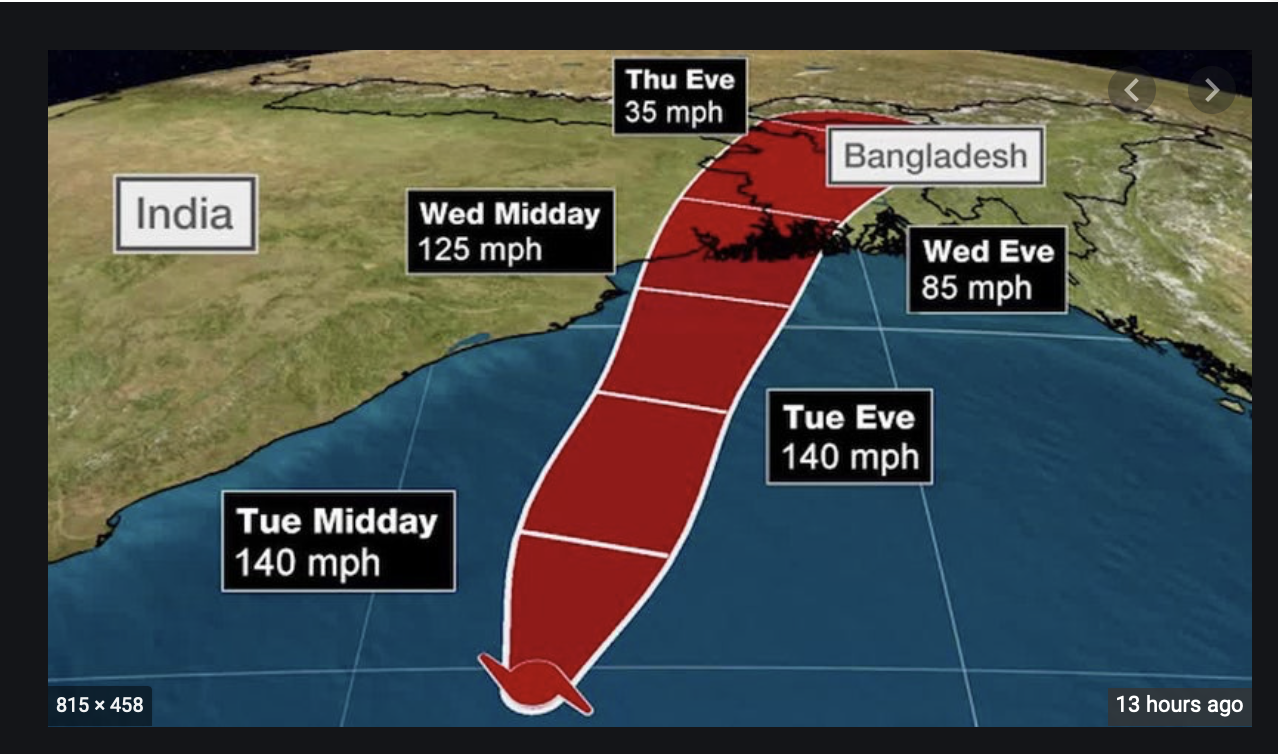

As I began my fall semester, I shared with my sociology classes details of my summer travel to Bangladesh and what I had learned about the Rohingya. My most intense learning took place by meeting with many Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar in southern Bangladesh, not far from the Myanmar border. Though most of the Rohingya diaspora is located in Cox’s Bazar, those fleeing the genocidal Myanmar military now live all over the world. Ziaur’s story takes place mainly in Malaysia, but includes experiences chronicling his many experiences since being exiled from Myanmar as a 17 year old.

As part of my classes I have students choose books and require reading them through the sociological lens they are learning. Below is a review of Survivor written by one of my top students, Gabriele Miller. Though her review uses some sociological jargon, her essay conveys how she was moved by reading Ziaur’s words.

Book review by Gabrielle Miller

“Survivor: My Life as a Rohingya Refugee” by Ziaur Rahman proved to be a very difficult read for me. Growing up in America, I have inherited a polished view of life. Ever since I was a child my parents raised me to do good in school, attend college, and find a career that made me happy. Marriage, creating a family, and working to help our family survive are things that I have never had to consider.

I was able to get through the read because I assumed that the book was written by someone a lot older than me. I tried to distance myself from the text to protect my reality. However, after a conversation with Dr. A, I found out that he knows Ziaur Rahman. When Dr. A said “I know him” I was taken aback, it made me realize how interconnected the world is and how dangerous it is to get caught up in a polished reality. Throughout this essay, I will introduce the main points that I found difficult to process as an American.

difficult to process as an American.

Main themes

Mistreatment of Refugees

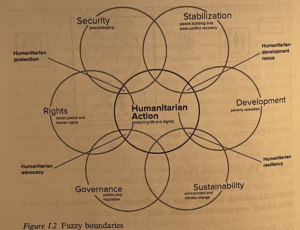

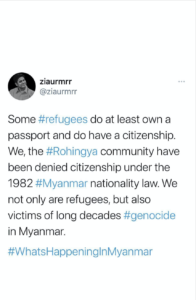

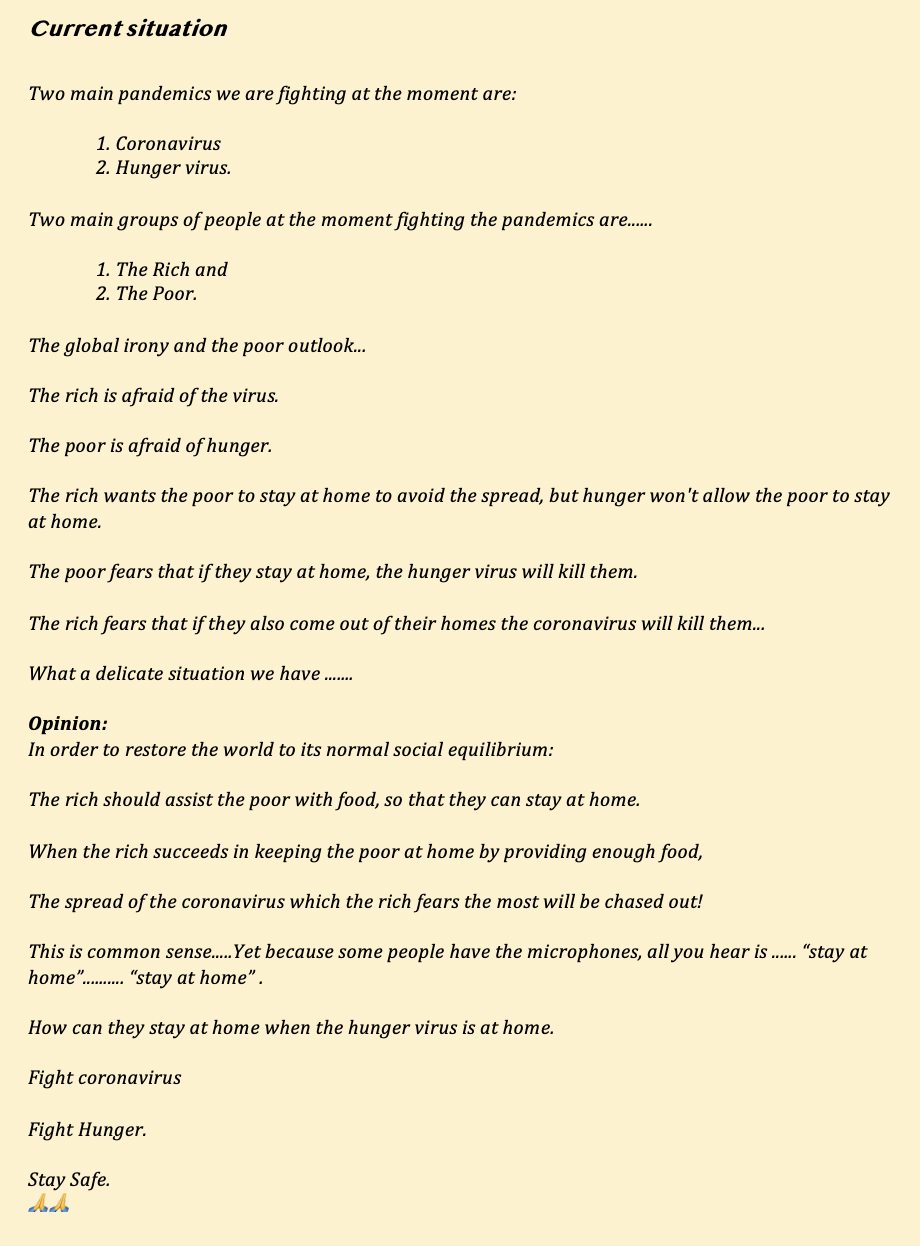

The main theme throughout the entire book is the mistreatment of Rohingya people. That mistreatment comes from the governments of both Bangladesh and Myanmar, and even from traffickers who kidnap and ransom the refugees to their already very poor families. Personally, I had a hard time digesting the fact that both symbolic violence, and systematic violence that the refugees must endure are manifest functions of deliberate acts. While causing direct pain was not the reason the Rohingya people were displaced, the government of Myanmar knew that there would be troubling consequences and that people would lose their lives. They knew that it would affect the education, religion, and organization of the Rohingya people. I think the blatant act of revoking citizenship highlights structural functionalism within this situation.

Structural Functionalism Expansion

The Rohingya people are Muslim and the Myanmar government recognizes Buddhism as the “correct” religion. Due to their religion, Rohingya people were displaced from their land. The displacement has led to a downturn in education for refugee children. In the book, Rahman mentions multiple occasions when he had to pretend to be from other countries to create opportunities for himself. Their loss of citizenship has even affected the norms of their society.

Societal Norms

Marriage

In America, the norm is for the parent(s) or guardian(s) to take care of children. Marriage comes after education, and both (marriage and education) is a choice based on what will make you happy or successful (if your parents pick your path).

Reading this book I noticed that we as Americans are raised to focus on self, which is not necessarily negative, more so a luxury. Chapter 8 of this book is titled “Keeping Committed to My Mother”, and in this chapter Ziaur states “I couldn’t go against her and my relatives because I did not know how to refuse my elders. I always respected their word.” This reminded me of the exchange theory concept. Ziaur opposed marriage due to fear and the need to get away from the camp, however, the cost of not marrying (losing his mother’s respect) was not worth the unsure future. Due to the difference in culture, I could not imagine being put in this position. Trying to gain some understanding I found that the Rohingya people marry this way because it is traditional. The marriages also protect women both physically and culturally. Unmarried women have a harder time than women with a spouse because of how prominent human trafficking is (Abdelkader).

Prision

I also found it interesting that in this same chapter Ziaur lost his job, was required to quit school and imprisoned. As the story goes on he includes many people, like his uncle, that have been imprisoned or are “released prisoners” (people that have served their time but must stay in the prison because the Myanmar government refuses to re-admit them. “Released Prisoners” are a perfect example of the toxic othering that exists within the Myanmar and Bangladesh societies. They view the Rohingya people as introducers which leads to their prosecution. The toxic othering of both governments and their people lead to conflict theory. Within the Myanmar and Bangladesh communities, power is unevenly distributed. This results in the “Rohingya people of Myanmar, who have lacked human security since Burma’s first military coup in 1962 (Mahmood).”

Conflict Theory Expansion

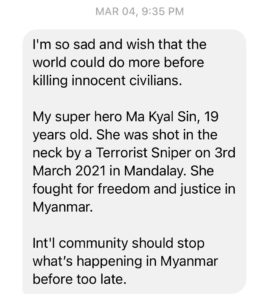

The systematic issues in the book are in no way basic but understanding conflict theory allows for the expansion of how deeply rooted the issue is for the Rohingya people. Money and resources will help but also keep them in the situation they are currently in. The only thing people can really do is advocate, for any 1 nation to speak out could be to create more enemies than allies and it is highly unlikely that the United Nations will go as far as implementing mandatory regulations. In this situation finding a solution is so difficult because the hate is not only systematic but cultural. People will not fight for the Rohingya people because they are afraid of the consequences of their government.

Connections to other Presentations

Ziaur Rahman uses his personal experiences to try to get the audience to understand the risk of being born a Rohingya refugee. I find it incredibly noble that he uses his story to advocate for the lives and wellbeing of thousands of people. Before the book starts he includes a poem he wrote titled “Run, Rohingya, Run” in it he writes “I tell you, shout this out to your folks at home Being Rohingya is not easy Our hearts bleed”.

The fact that he is using his story to demand the recognition of his people reminds me a lot of the presentation Echos of Home. Both books use difficult yet necessary vividly illustrated stories to express the urgency of the situations of these people.

I must admit reading the story even from a sociological perspective I failed to understand what impact I could possibly have on such a vast and government rooted issue. That’s when I realized that reading the story and presenting was a small way to advocate, it is the sharing of knowledge that creates impact. As Americans it is our job to take off the polished glasses and see the world in order to help. As the book states “we don’t want money, simply the resources to get on our feet and help ourselves”.

Additional thoughts

We live in an increasingly complex and globalized world; there are an endless flow of major stories to be absorbed and it is easy to become overwhelmed. We all take in what news we can and then go back to our day to day lives. But as a sociologist whose job it is to understand our social world, learning about our dangerous and complex world is our ‘day to day’ life. As an educator I am keenly aware that students are in different places emotionally, cognitively, and in terms of maturity. In my classrooms I do my best to avoid the ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ phenomena and take a more measured approach to presenting and discussing global social realities. That said, I do feel compelled to live up to our university’s mission statement which says, in part, “We integrate learning across the disciplines and put knowledge into practice, thus preparing students to be global citizens and informed leaders motivated by concern for the common good.”

Having already established herself as one of the best writers and thinkers in my class, when Gabrielle chose Survivor from my list of recommended books I knew she would do it justice. Her oral presentation of the book was paired with another top student’s presentation of a book of poetry written by a Rohingya refugee. Another of my excellent students, Mason Cormany read and reviewed Echoes of Home by Sayedur Rahman, and before both of their in class presentations I did a short history and overview of the Rohingya situation, providing context for their classmates. Both Mason and Gabrielle are on their way to becoming exemplary global citizens and by their actions demonstrating a ‘concern fort the common good.’

Strong recommendation

Both Survivor and Echoes of Home are exceptional reads which will help any reader expand their understanding of the Rohingya people and their struggles. Over the last half decade I have read countless poems, essays, and books written by members of the Rohingya diaspora, and these two works are among the best. Buy them, read them, and grow as a global citizen. Together, armed with more understanding and empathy, we can all work for the common good of all humanity.

Follow

Follow