White savior complex

[Updated 22 April 2019]

More preliminary results

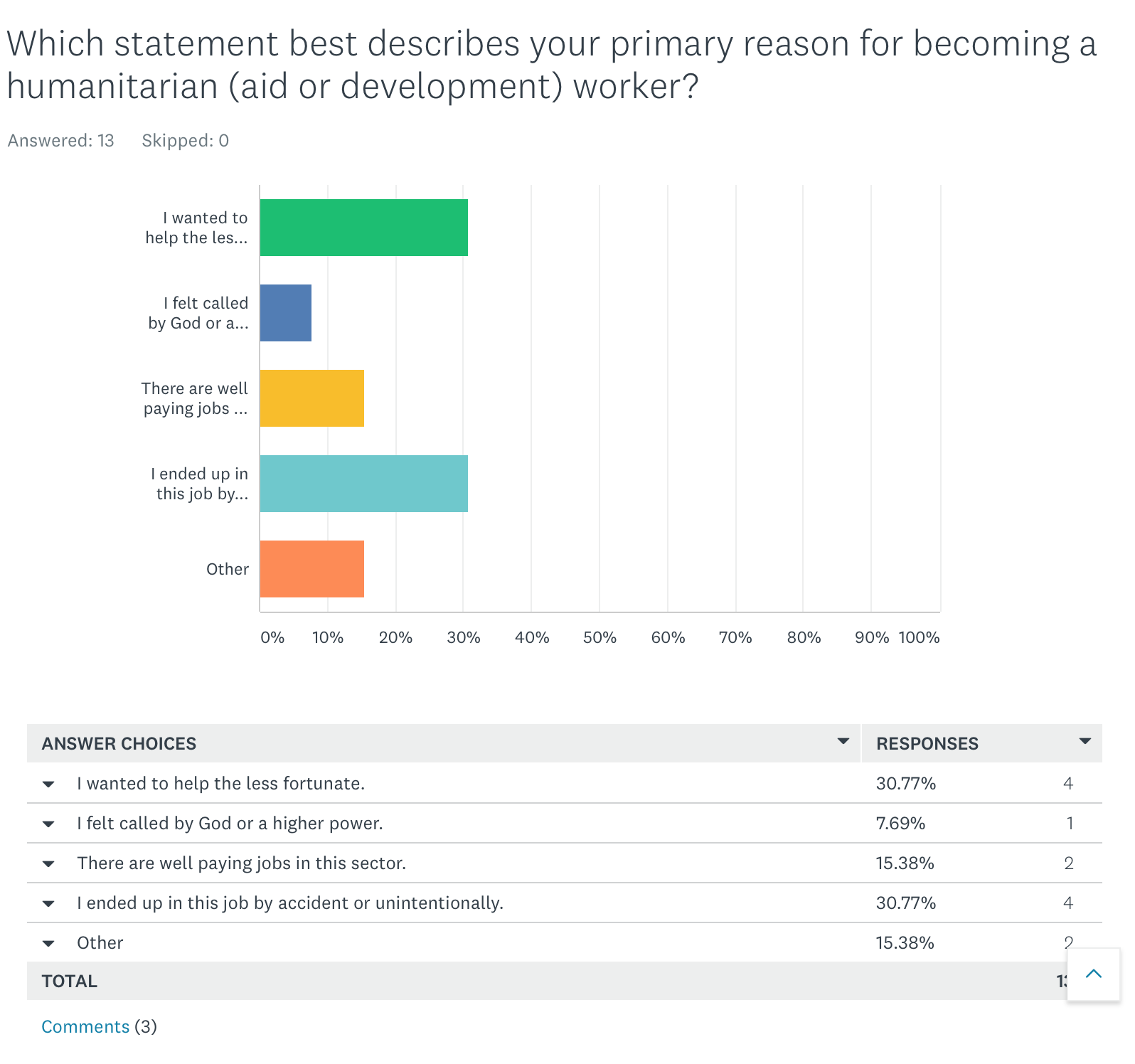

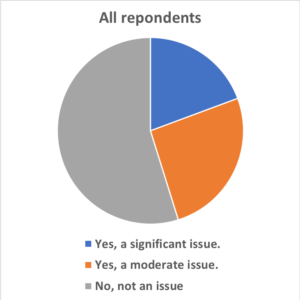

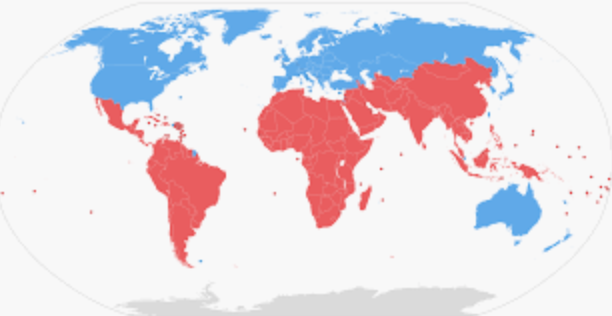

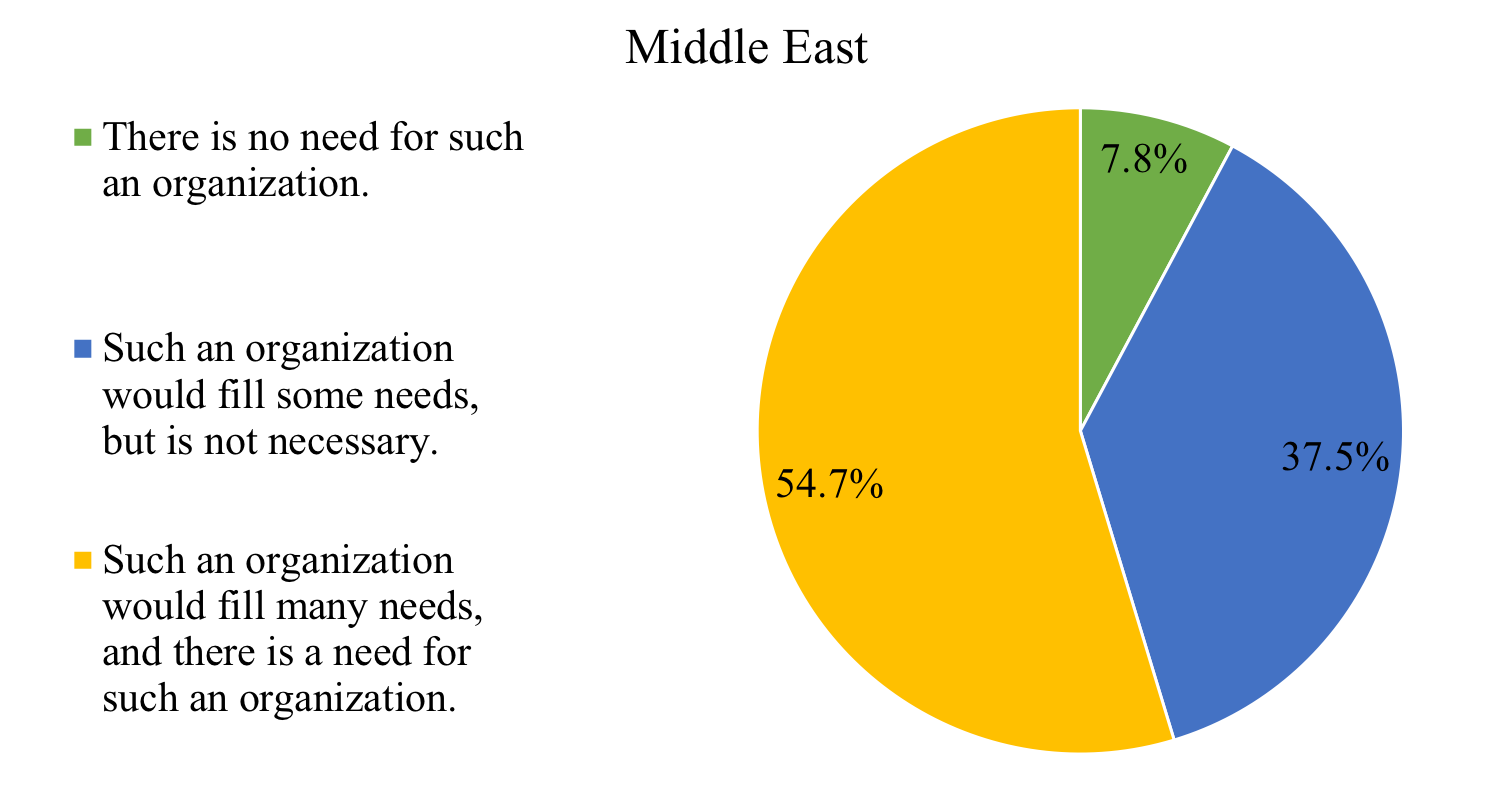

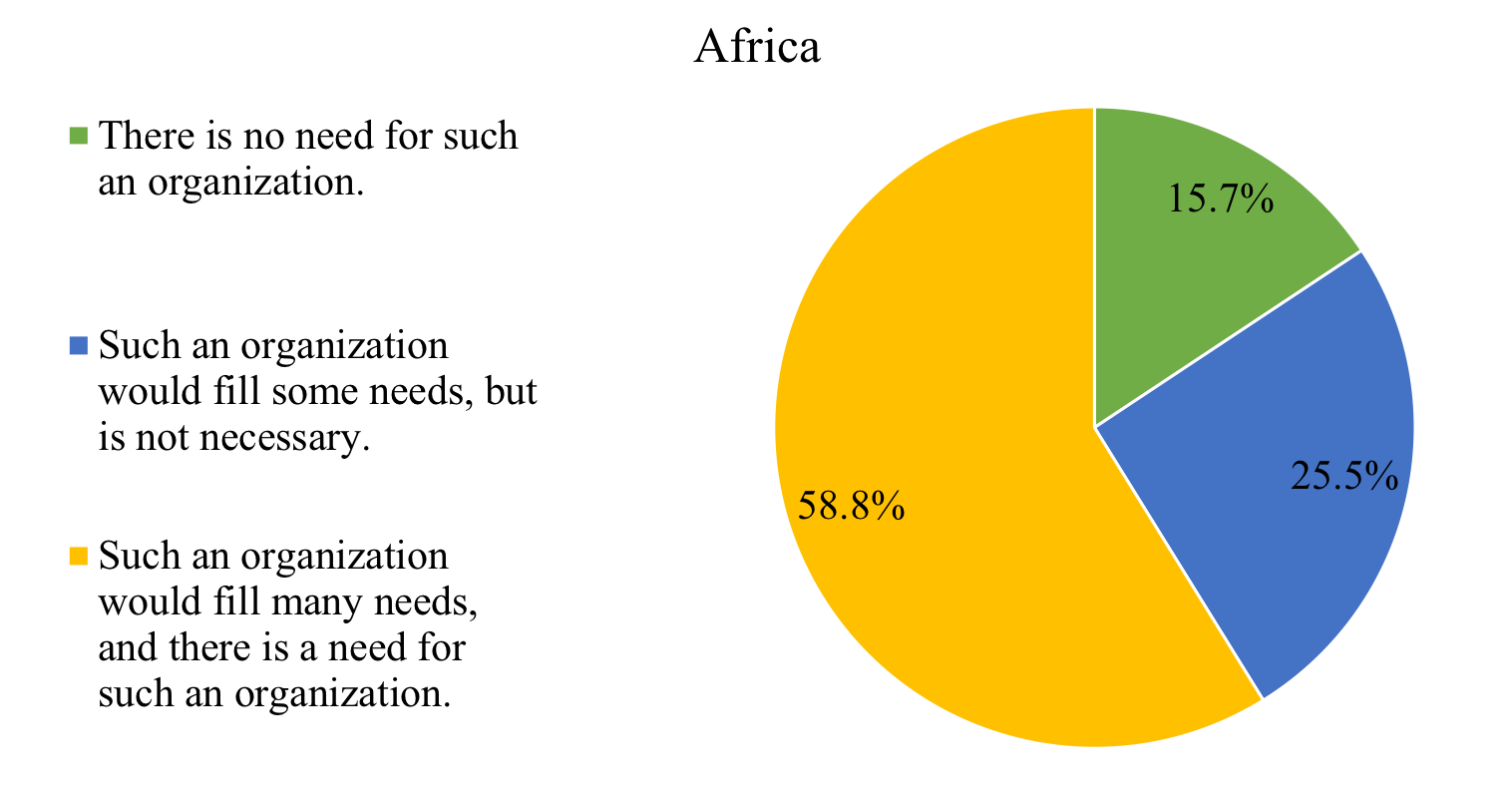

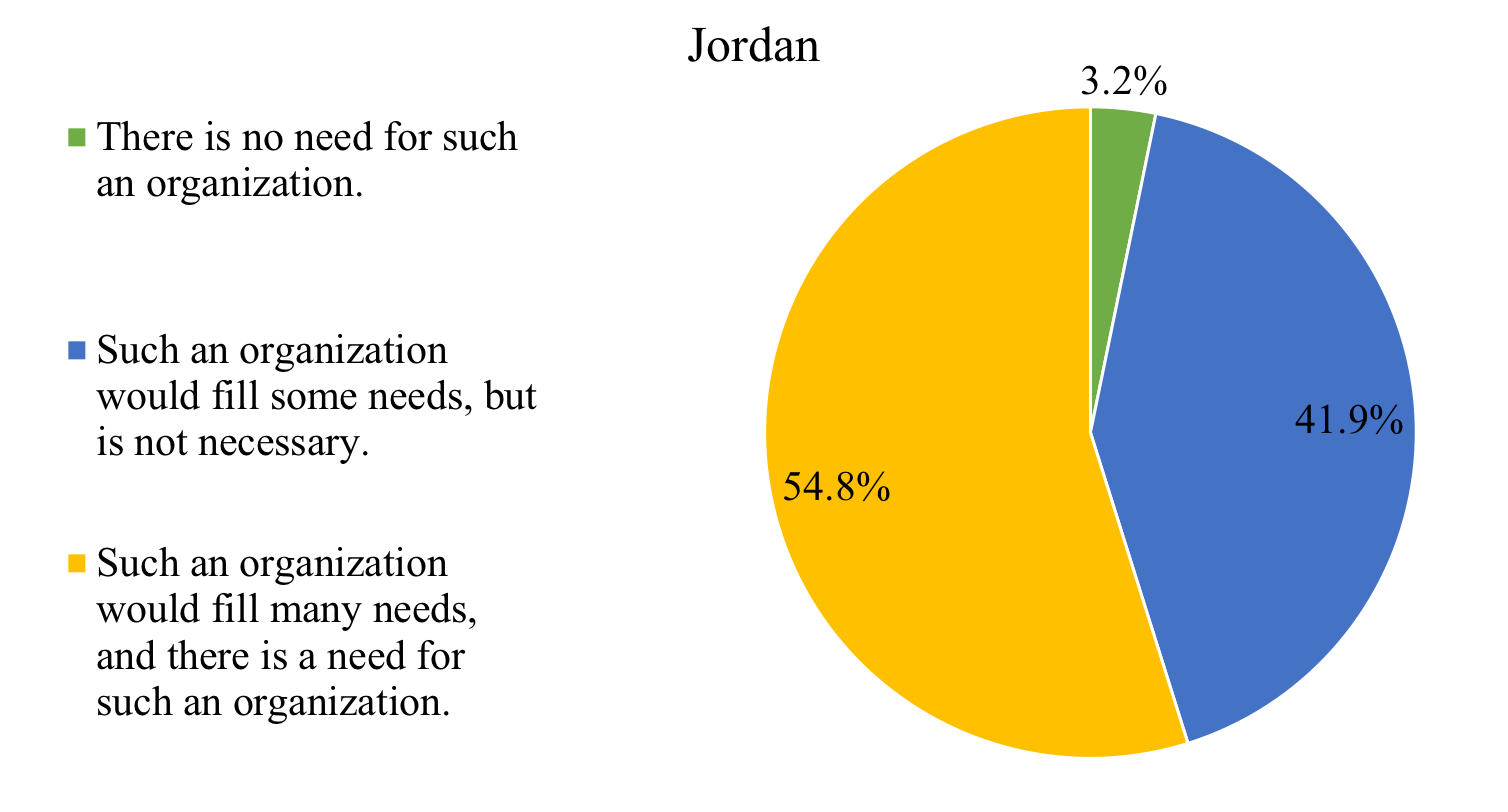

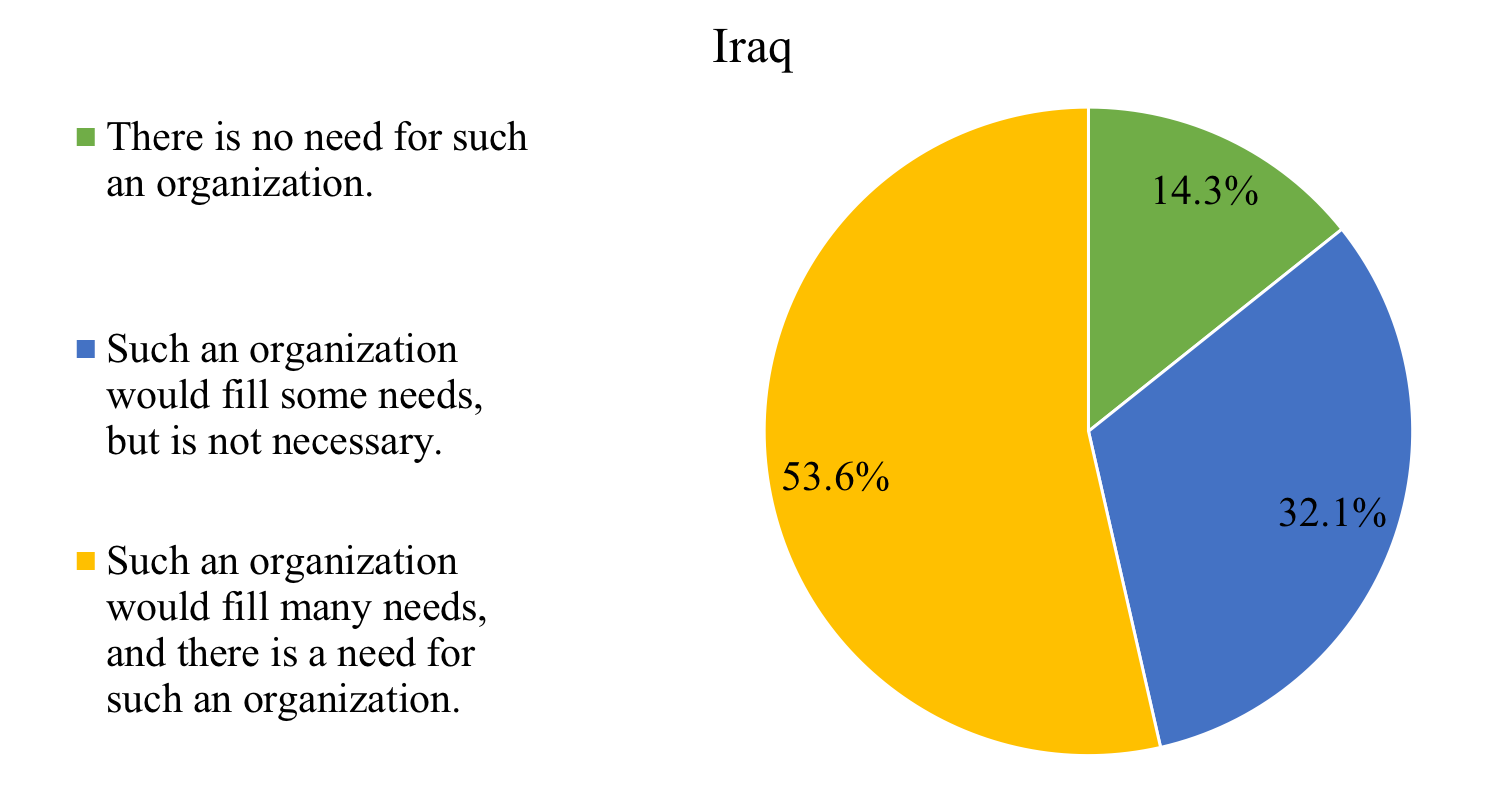

One month ago I posted a very early glimpse at the data coming in from our survey of humanitarians from the ‘global South’. At this writing we have 120 responses from over 16 different nations from all over Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and even the Pacific  islands.

islands.

When the survey does close there will be a full analysis and reporting of the data, but until then I will continue to scan all responses and report trends and themes I see emerge. [Note: If you are a national (‘global South’) humanitarian and would like to participate in this survey click here.]

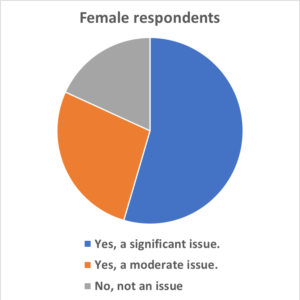

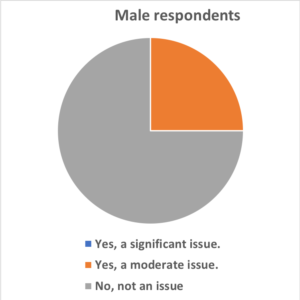

In my earlier post I reported on questions related to #AidToo, noting that there are two questions on the survey hitting on that topic. As more data come in, the results remain somewhat consistent and predictable on those questions. In short, yes, the results indicate a problem with sexual harassment or exploitation both between humanitarian staff and between humanitarian staff and the affected community. More on that later. This post is about systemic ‘baked in’ racism.

White savior complex

Humanitarians are very quick to point out instances of what has come to be called the ‘white savior complex,’ especially among those outside the sector and sector ‘wannabe’s’ doing voluntourism. The ‘white savior’ trope has been active for many years, certainly predating Teju Cole’s March 2012 article in The Atlantic The White-Savior Industrial Complex which was based on his reaction to the Kony2012 video. Cole’s article garnered a great deal of attention and has shown great staying power, becoming part of the cannon in the ‘anti do-gooder’ literature.

Recent critiques of the ‘white savior complex’ are wide ranging and include the “White Savior Barbie” parody site (Barbie has her own Instagram page), the kurfuffle over Louise Linton’s memoir about her gap year in Zambia, In Congo’s Shadow (one Zambian called the book ‘Conradian racist rubbish’), and the (seemingly) annual controversy over Comic Relief’s ‘Red Nose’ fundraising efforts. There has been an uptick of comments and articles about racism in the humanitarian sector lately, though much more light need to be shed. Still not sure about the white savior complex? Resources and information can be found on a fairly new web site organized by some humanitarians from Uganda. Visit No White Saviors.

Two respondent’s views

To what extent does ‘white savior’ behavior exist within the humanitarian sector?

There is no simple way to measure this phenomena for many reasons, not the least of which is that there is no agreed upon operational definition of this term. I’ll work with my national  humanitarian colleagues and see if we can arrive at a reasonable and measurable list of indicators, but in the meantime it will remain as is, a useful referent.

humanitarian colleagues and see if we can arrive at a reasonable and measurable list of indicators, but in the meantime it will remain as is, a useful referent.

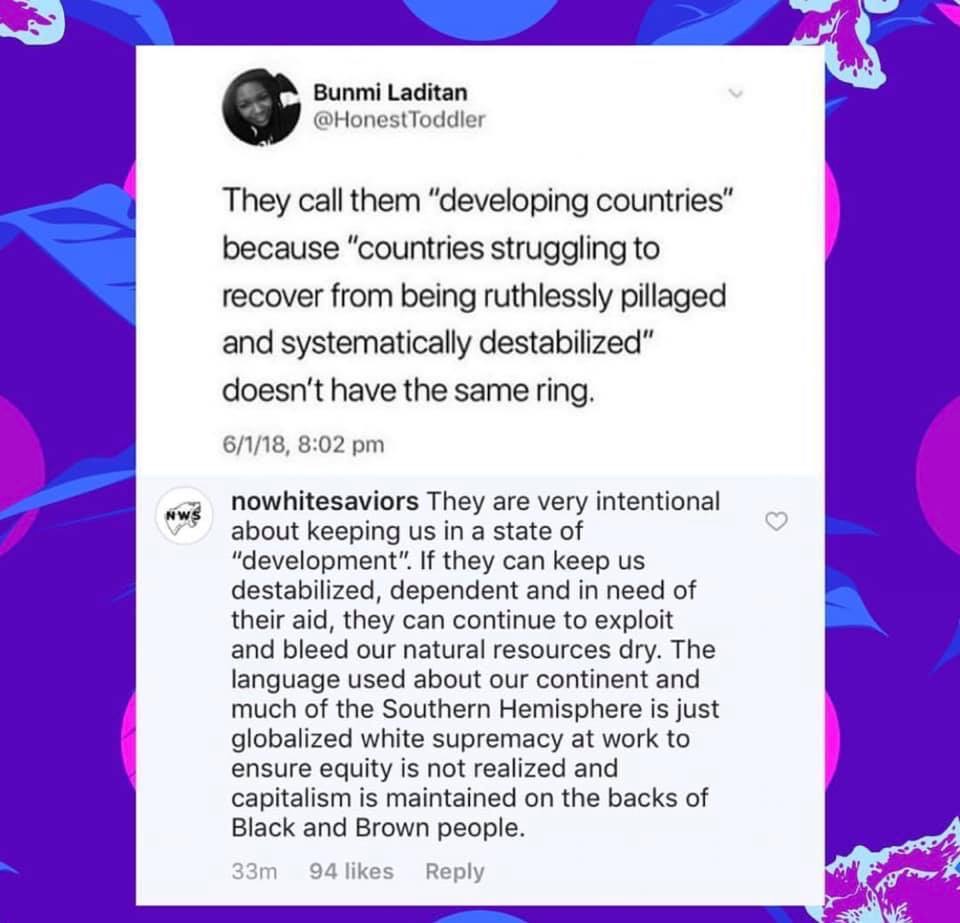

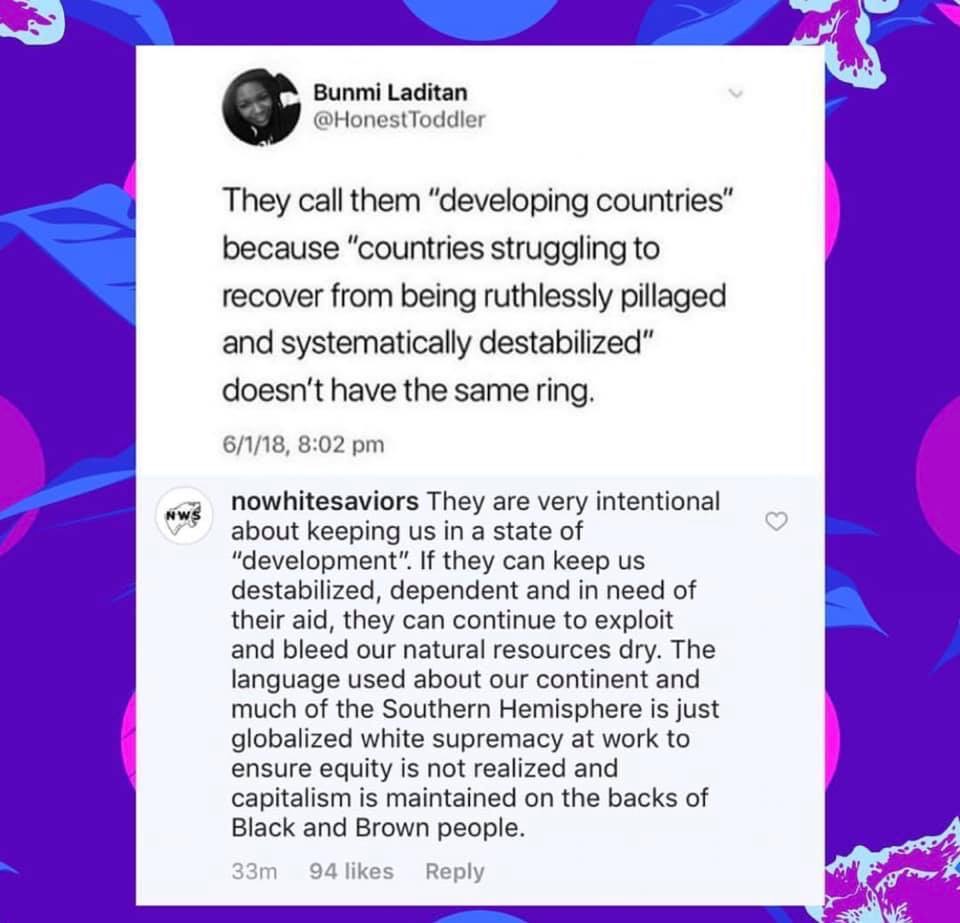

As I was drafting this post I came across this Tweet (see right) on my social media feed. Much truth there, methinks, all relevant to understand as we parse out the many nuances of ‘white saviorism’.

Bunmi Laditan states, “They call them ‘developing countries’ because ‘countries struggling to recover from being ruthlessly pillaged and systematically destabilized’ doesn’t have the same ring.”

And then ‘@nonwhitesaviors’ notes, “If they can keep us destabilized, dependent and in need of their aid, they can continue to exploit and bleed our natural resources dry.”

Adding an even more egregious example, I’ll quickly insert the ongoing controversy related to the $23 billion that Haiti paid to France for its independence, dramatically hindering the new nation’s economic development.

Most who work in the humanitarian sector -both from the global North and South- are acutely aware of the colonial past and how this past has directly and indirectly contributed to many economic, social, and political ills. But to state the obvious, there is a dramatic and critical difference between an academic outsider’s view (global Northerners) and the the one lived by those who dwell in nations with a past marked and modified by colonization.

With all that in mind, here is what one woman said on the survey,

“White saviour mentality is difficult to compete against. Sometimes even beneficiaries would rather listen to the nice westerner who is giving them the wrong advice than national staff who know what is right. Many times national staff can’t even stand up and correct people who are coming in with irrational idealistic ideas that do more damage than good. So we sit and watch things crumble… and then the saviours leave, and locals are left to pick up the pieces alone, trying to explain to beneficiaries what went wrong. Then in local communities, just by sheer association, we are either seen as traitors or are expected to provide the same freebees that the westerners used to give.”

-female humanitarian from Kenya

Before examining her comment in more detail, it may be useful to provide some context. Backed by the rhetoric of the Grand Bargain, the stated goal of many humanitarian organizations is to make incremental progress toward the (ill-defined) goal of ‘localization’, albeit with a myopic focus on the ‘financing gap’ in aid and development. Here is how Charter for Change phrases it: “An initiative, led by both National and International NGOs, to practically implement changes to the way the Humanitarian System operates to enable more locally-led response.” But regarding “Localisation of Aid: Are INGOs Walking The Talk?” Perhaps not in all cases, it would seem, and this brings us back to our respondent.

There’s a lot to unpack in her statement.

- It is very clear from her tone these words come from a place of high frustration “….So we sit and watch things crumble” and ”we are seen as traitors…“

- One of the more insidious legacies of long term Western/white colonialism is the deeply baked in nature of racist assumptions that can permeate the consciousnesses of both the ‘outsiders’ and the indigenous (‘local’) peoples, as in this respondent’s lament, “Sometimes even beneficiaries would rather listen to the nice westerner who is giving them the wrong advice than national staff who know what is right.“

- Sometimes the core mandate of all aid and development work “first, do no harm” seems to be at risk. Her statement infers that efforts can “go wrong” and need to be fixed after the “westerners” leave.

- One final point she makes is fallout from the outside efforts is that the local humanitarians “…are expected to provide the same freebees that the westerners used to give.” What these freebees may be, I am not sure, but it is clear that this respondent feels she is set up to fall short in the eyes of the beneficiaries.

Another respondent said,

“As a global south humanitarian worker with both experience of working locally and internationally… I do feel white people have this sort of confidence on things they don’t know and global south staff having doubts but it’s not set in stone. People are different and there are incompetent people from different parts of the world. As a global south humanitarian worker, I have had to stand my ground a few times and felt condescended. Maybe it also counts that I am younger than many colleagues, and female.”

Taken together these two responses also indicate another ‘ism’ which is even more deeply baked into the histories of virtually all cultures. Sexism exists in many forms all over the world, and it is no surprise that it also can be found manifesting itself within the humanitarian sector. A deeper look into this issue will have to wait for another post.

White savior mentality

These two responses are just that, two responses. There are more comments from others and ample quantitative data yet to be analyzed (and more data yet to be collected, of course). One critical point I will offer is that the white savior mentality is -in many cases at least- not overtly intentional; the ‘westerner’ may not even realize that sh/e is perceived to be embodying this mentality.

and ample quantitative data yet to be analyzed (and more data yet to be collected, of course). One critical point I will offer is that the white savior mentality is -in many cases at least- not overtly intentional; the ‘westerner’ may not even realize that sh/e is perceived to be embodying this mentality.

Indeed, we may be stressing the wrong unit of analysis, only seeing the “white savior mentality’ to be characteristic of individuals. Perhaps more so, this mentality is woven into the very fabric of the humanitarian organizations and indeed the entire humanitarian ecosystem. As much is inferred in Cole’s original phrasing ‘white-savior industrial complex’ (emphasis added).

Post script: ‘Saviourism’?

I had one sector veteran suggest that we could perhaps just use ‘Saviourism’ or ‘Saviour Complex’, inferring that even some non-Western POC operate at some level motivated by a desire to ‘save’ other people from their circumstances. Let’s examine that thought.

I am reminded that although historically race is an ugly and rapacious divider, social class/caste has through the ages also worked in a similar manner, renting apart peoples and ossifying layers of privilege. In addressing class inequalities, most faith traditions around the world, and most certainly the three Abrahamic religions that dominate much of the globe currently (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism) encode in their major documents and preach on a regular basis that it is the duty of followers to ‘minister to the poor.’ ‘Saviourism’ is indeed woven into the fabric of many cultures -in both the global North and South. Point granted.

That said, the trope ‘white-savior industrial complex’ as popularized by Cole’s The Atlantic article explicitly and specifically calls attention to race, not class. I will leave this as a question: Is it possible that the use of the more ostensively inclusive term ‘Saviour complex’ is in the same category as saying ‘all lives matter’?

More to come soon. In the meantime, please contact me if you have any questions, comments, or would like to talk to me about the ‘global South’ survey.

Tom Arcaro is a professor of sociology at Elon University. He has been researching and studying the humanitarian aid and development ecosystem for nearly two decades and in 2016 published 'Aid Worker Voices'. He recently published his second and third books related to the humanitarians sector with 'Confronting Toxic Othering' published in 2021 and 'Dispatches from the Margins of the Humanitarian Sector' in 2022. A revised second edition of 'Confronting Toxic Othering' is now available from Kendall Hunt Publishers

More Posts - Website

Follow Me:

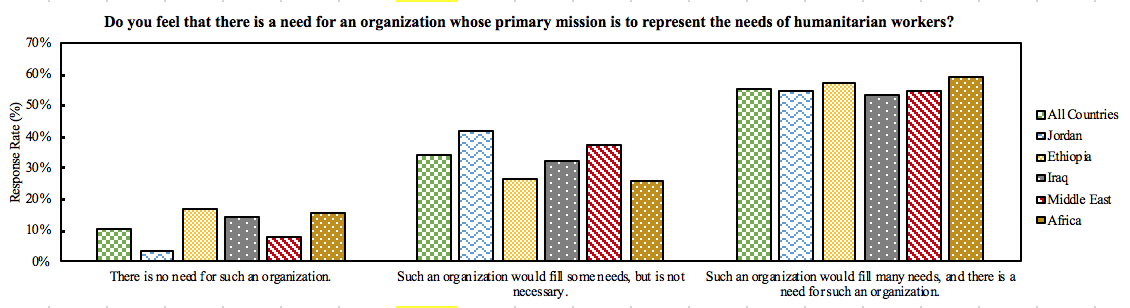

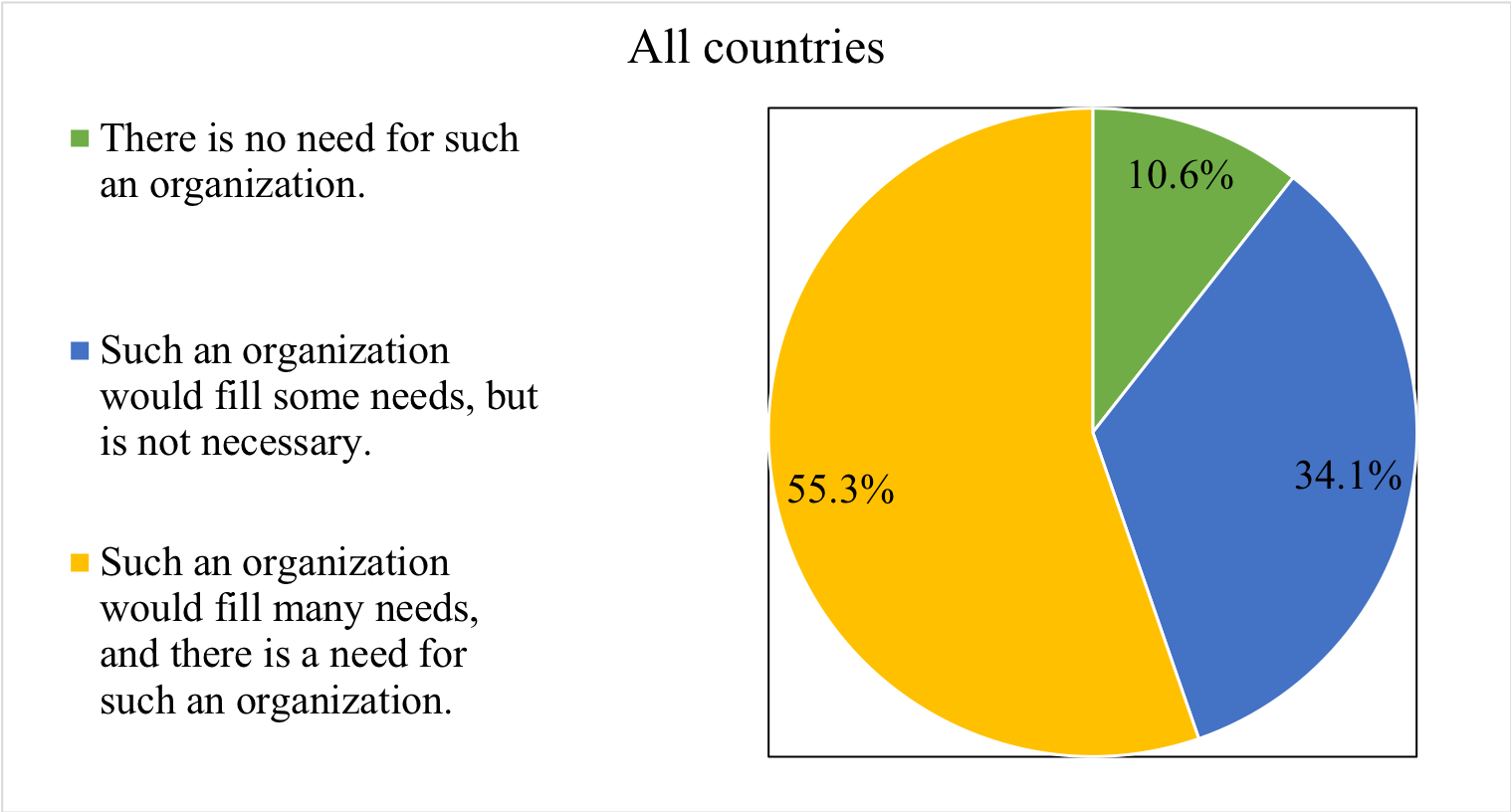

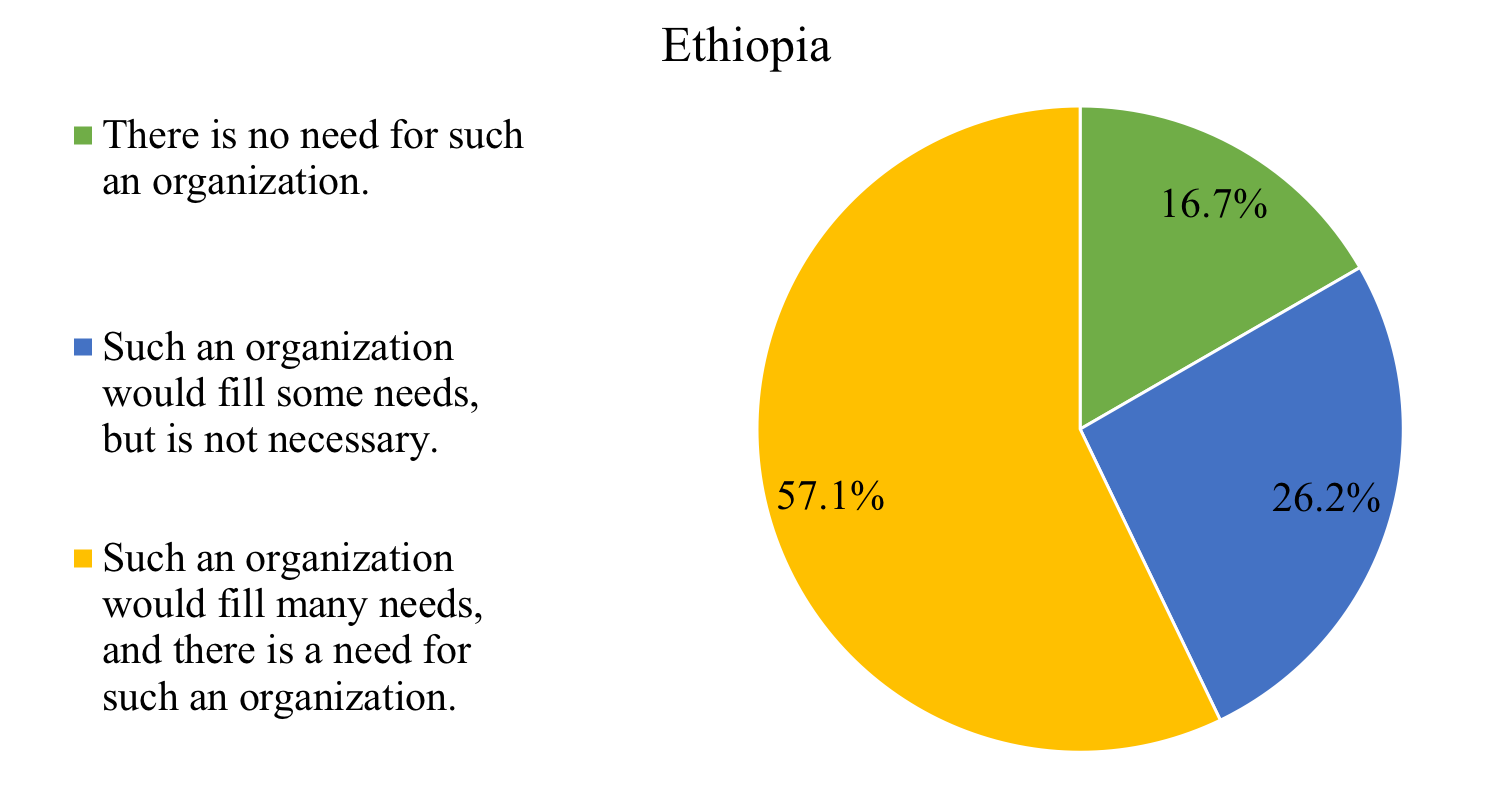

“Do you feel there is a need for an organization whose primary mission is to represent the needs of humanitarian workers?”

“Do you feel there is a need for an organization whose primary mission is to represent the needs of humanitarian workers?”

Follow

Follow