How do you explain your job to non-sector people?

“I definitely understand why dating within the aid worker population is appealing. Conversations with laymen are hard. I think I only try once in a while, usually when I’m unusually overwhelmed or frustrated and it kind of comes pouring out. But it’s exhausting, because you realize how many words you need to use just to catch the person up on why something is as vexing as it is. It’s such an intricate environment.”

– female HQ worker

“Entirely depends on the person, and their previous knowledge level and the degree of real interest.”

– female expat worker

“As long as I return alive, that’s all she cares about. Fine by me. It’s better she does not know.”

– male HQ worker

Sharing

With whom do you share details about your life as an aid worker? Under what circumstances? At what level of detail? How do you simultaneously honor the intense privacy -yours and others- of your field experiences and at the same time your deep need to share fully with intimates ‘back home’? What do you tell and what do you hold back? How do you deal with the inevitable need to put into separate compartments the roles that you play at work and at home?

The topic of this post is, in the end perhaps, efforts at mental hygiene as aid workers grapple with living out complex professional roles while at the same time attempting to have ‘normal’ social and family lives.

Below I focus on the questions 33-38 on our survey which asked respondents about the challenge of explaining the nature of their job to those around them, namely friends, lovers, family and children in their lives. The 1048 total narrative responses were fascinating to wade through. While many were short and minimally responsive, there were countless comments that shed useful and nuanced light onto our research questions about how aid worker’s explain their jobs.

Explaining your job

Aid workers have a job frequently misunderstood by the general public; stereotypes abound, some positive, others not so much. How many times have you heard, “Thank you for all you do!” “Wow, you get to travel to exotic places!” or “Oh, you are one of those arrogant bastards trying to export Western lifestyle in all parts of the globe.”?

But is this situation unique to aid workers? Likely not. Here is what a couple respondents pointed out.

“Its impossible to really understand without having the context. There are things my friends try explain to me about their lives that I have equally no context for – and is equally difficult. So I see the same issue on both sides.”

“I would never expect people to be as well-educated on all the various aspects of aid work — including all the criticism, rather than the “do-gooder” stereotype, which makes me uncomfortable. Just like they would never expect me to understand the ins and outs of their professions. It’s just that their professions may not be as controversial or receive so much media attention. Specifically, I work on a very awkward area of maternal health — women with obstetric fistula leak urine and sometimes feces from their vagina. It’s not dinner conversation (which is part of the reason it’s so marginalized even within global health circles — people don’t want to talk about it because it’s embarrassing). So I usually say only very generally what I do and try to be very gracious when people talk about “all the good work being done in Africa” or whatever. I’ll only go more in-depth if I can gauge a genuine interest that they want to hear more of the real stuff.”

This next aid worker gives an example that I can personally relate to as a university professor whose own spouse continues to ask “What are you doing when you are not teaching a class?”

“It could also be interesting to compare these answers to those from people doing other kinds of jobs. I guess complex work is always difficult to explain. I guess many people *think* they know, for instance, what a professor does, but many would be surprised to learn how little time is actually spent teaching or doing research as opposed to other tasks such as writing grant proposals, acting as editor or reviewer for some journal, organising conferences, responding to emails, etc. What makes aid work different is that many of the existing stereotypes and preconceptions have a negative connotation (white saviour, proselytism, exporting Western democracy /capitalism…). This means that aid workers who want to explain their jobs need to dismantle prejudice, whereas the professor from my previous example can honourably get away with “yes I do teach undergraduate classes among other things”. Also, ‘aid worker’ is terribly generic and lumps together the war surgeon (something not too difficult to explain, albeit extremely difficult to do) with the fundraising or the monitoring and evaluation officer (less easy to explain).”

Fair enough. The cultural and social worlds we inhabit often are very different one from another and we all often make the mistake of assuming a sharing of understanding where that is not the case. Getting into the details of any occupation can be a rabbit hole of nuance and complexity, but perhaps aid workers have it a bit more difficult because of the added layer of shifting contexts. Indeed, aid workers are occupationally different from most jobs in that they frequently must transition from one cultural content to another.

But why would you want to explain your job? The answer is simple: we are a social species and our mental health and happiness are in large part dependent upon having family and friends with which we can express and share emotions. The natural urge to share one’s life with intimates is stressed by the aid worker’s job. The voice below is describing a situation where, I suspect, unwanted barriers are being created.

“None of my family or friends back home have ever done aid work before and many rarely travel overseas. Thus most of them don’t seem to be able to understand why I work overseas in one of the most violent and stressful contexts. This lack of understanding often creates a gap which makes it hard for them to contextualize the work and lifestyle in country. Sometimes this means they avoid asking too many questions.”

Parents, siblings, in-laws

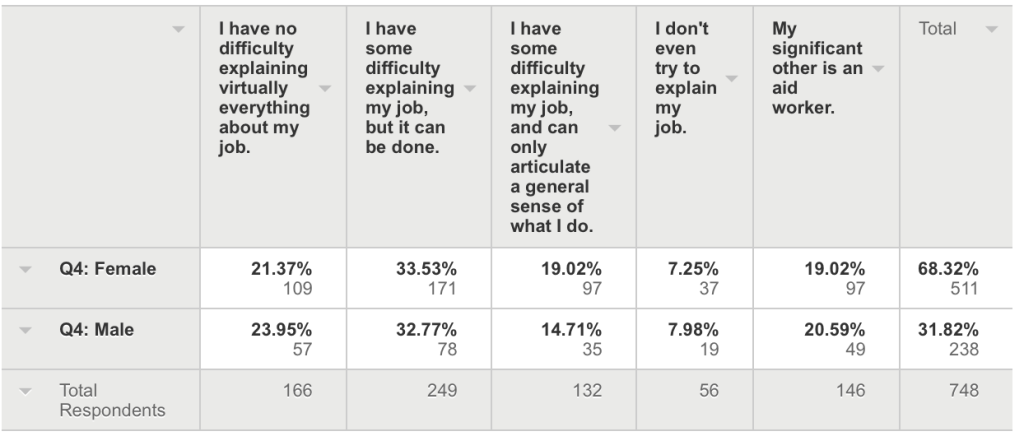

Q33 asked, “Which statement below best describes your ability to explain to non-aid worker non-significant other adult family members the nature of your job?” Rising above the awkward wording in the question were 426 respondents offering some comment regarding difficulty explaining their job to parents, siblings, in-laws and others close to them. I’ll preface this section by pointing out that there was a subtle but, I feel, telling difference in how men and women responded. The results below indicate that women tend to have a much more trouble than men explaining their job. The differences highlighted in blue are statistically significant.

That the quantitative male and female responses differed is evident, but having poured through the narrative responses -first female then male the- ‘why’ lingers unanswered in my mind; no clear thematic differences are evident in the narrative responses.

Difficulty of explaining depends on the audience and on what job you have

In looking for themes in the narrative responses it was clear that the level of difficulty and frustration with communicating about the job was directly correlated with (1) the nature of the aid/development work being done and (2) the level of education and/or cross-cultural literacy of the people the aid worker was trying to communicate with. These first two illustrate clearly that explaining the job is clearly not “one size fits all.”

- “It’s too complicated to get through the layers of assumptions, stereotypes and cliches; most of my family seem to think i’m on a vastly extended gap year, in a comic relief sort of way. They don’t know the kind of money and resources i oversee or the complexities of the work. I think too if i described to them what i actually work with, they wouldn’t be able to hear it as it is hard to think about directly. For some of them, the response is ‘well, you chose it’ if i mention any difficulties. For others, there’s almost a resentment connected to ‘oh you’re so worthy’ which i don’t completely understand. A couple of my close family know what i actually do to a greater degree and are proud of me. Mostly i think people start with an assumption that they know what it is and it’s too hard and too boring to get into why it’s not that. In addition, my technical area of violence against women is not something people generally want to think about or talk about too much – and there are also a lot of assumptions about this too.” -41-45 yo female HQ worker

- “This depends on the person. In general, I try to gloss over the bad stuff and just focus on the good stuff. Or if I talk about the bad stuff I complain about the food or not having any personal space and I leave out the dead babies unless someone asks a direct question.” -31-35 yo female HQ worker

If the family/friends back home have similar experiences or are otherwise cross-culture savvy, explaining the job can be easier.

“The difficult is more on the technical side as I come from a family that includes development workers, although not humanitarian aid workers, so the motivation is not difficult to explain nor is the sacrifice on family time, personal safety, material comforts.”

“My family has tried a lot to understand what I do. My parents even took a SPHERE training course and get often ask me if I am keeping up with standards when I am on the field. They also understand the Faith component of my motivation to work. But it’s the relationships and the tension, the raw side of the responses that people don’t understand. They don’t have the frame of references to understand the extreme pain, poverty and insecurity seen on the field. But they try and I love my family and friends for that.”

If your job is in medicine or communications explaining is pretty straightforward.

“Since I work in field communications, it’s not as difficult to explain that I help in the process of obtaining stories of the people who benefit from our programmatic work. If I need to explain the development models in more depth, that could be harder depending on who I’m speaking to and their level of interest and comprehension, but I’ve done it long enough now that it’s quite second nature.”

Persistent misconceptions and oversimplifications

There were many responses voicing a frustration that despite best efforts otherwise misconceptions and oversimplifications, most framing the work as simplistic and/or charity, persisted. Others marginalized the work by reframing the mission of the sector, as in this first example.

“My adult family members question the difference between development work and the invasion of Afghanistan, feeling both are western imperialism – one just happens to be at gun point.”

The next few are typical in describing the entrenched stereotypes of aid workers.

- “For years, I basically said, ‘no, I do not hand out bowls of soup.”

- “I have difficulty explaining that I am not a white savior protecting the orphans of Africa from dreaded disease and war.”

- “I am a funding policy adviser. My role is to advise donors and advocate for best funding practise on behalf of a membership organisation of international NGOs. My mother thinks I rattle tins at supermarkets to get coins to give to starving Ethiopians.”

- “‘So you dig well for Africans, right?’… ‘No, darling brother, I am a fundraiser. I work at a desk and deal with bureaucrats all day’… ‘Cool. So how many wells did you dig this year?’… and repeat.”

- “I’m not a nun. I don’t distribute soap.”

These next few voices, I am sure, speak for many. I love the ‘bridge-building imagery in the third one.

“I’m tired of the whole, “oh you’re in charity work?” the platitudes about helping the needy, and the inevitable insta-generalizations about people from the place I’d most recently traveled to.”

“It is all but impossible to explain that aid isn’t always good and that the UN can’t solve shit. We’re not heroes and most of us are career bureaucrats just like any other work. But people hear “Africa” and know I must have saved thousands of starving babies, even if I don’t work for a nutritional program.”

“It’s a long bridge to build from where I work to “every day” life in the US. It takes time, which sometimes people don’t have, but people seem genuinely interested and listen. That’s all I can ask. Sometimes I get bizarre and bigoted questions, but as you know Americans are generally clueless about the world.”

Many specific jobs just don’t translate well, so some aid workers resorted to comparing the job to something with which the family member might have some referent.

“First of all it is very difficult explaining the difference between charity and aid/development and especially when it comes to long term community development. Non-aid workers do not really grasp all the theories that go behind why or how we do things. Second of all, my work is strategy and M&E and so am not really a front-line staff so that makes it even more difficult. I sometimes try to compare it to “auditing” but even that is not even close to what I do.”

The accumulated frustration of trying to explain the job generates various responses. The first example provides with a nice visual.

“They don’t really get it, so I keep it simple. They think I am in Africa working with kids. Its a lot more complex than that, but taking time to explain details would be enough to make me want to jam a fork in my eye.”

Are you a spy?

There were many interesting themes but one that I thought was both amusing and telling is that more than a few mentioned that their family or friends suspected that they might be doing something other than aid or development work, namely that they were secretly CIA. These suspicions are legacies of the Cold War, but they also point out the questioning cloud that can hang over this line of work.

- “Lots of people in my family though I worked for the CIA! All they knew was that I travelled a lot to weird places. It got easier to explain once I started working for an organization that was more focused, and and only one major, relatively specific purpose in mind, rather than some of the large development orgs that do just about anything and everything.”

- “My job these days is fairly straightforward. My previous job (involving democracy development) was nearly impossible to describe and my family all thought I was a spy. Humanitarian aid work is far more straightforward.”

- “They often think that I am, in fact, a spy.”

Selective telling: choosing not to share exactly what you do

In some cases aid workers choose not to share job related details. In sociology we call this ‘selective telling,’ and the most common reason found within our responses for this less-than-complete descriptions was, essentially, that some details are too stark, intimate and private, only to be shared with those who have seen the same. Here are some examples.

“The humanitarian aid worker experience is very hard to describe to others. Field work operates at such a constantly high level of intensity that even normal seeming activities become something else, which is nearly impossible to explain. The challenges and tragedies aren’t even worth explaining, because they are based in a completely unrelatable framework.”

“I am generally able to articulate what I do in practical terms but perhaps not to explain the emotional impact on myself – particularly in terms of what I see, the environments within which I operate and how they change me as a person.”

Selective telling might be a defense mechanism to avoid controversy or conflict.

“There’s a catch-22 in aidland – if you tell the outside any of what we fear/doubt on the inside, the field gets undermined… who wants to give their aid dollars to someone who’s not entirely sure what it does, or whether it’s aid itself (and the relief it provides from pressure for systemic change) that is a fundamental part of the problem?”

And, finally, showing the social grace to preserve civility and maximize useful understanding is another reason for selective telling as voiced so well by this next female aid worker.

“Other than that, I just wanted to add that I am one of those people who refrain from sharing too many details of her work: just too complicated to explain, and most of the times I’d rather avoid ruining a nice evening out by starting a debate on, say, the root causes of corruption or the role of country X in the Syrian conflict. What usually works is if I find ways to relate my experience to what the other person does: e.g. I explain that I write grants to people who are familiar, say, with research grants (even though grant-writing is usually just a small part of my duties), or I talk about procurement and subcontracting to someone who deals with these issues in their company, etc.”

The Lord

And, for comic relief -or not-, we had a response from AidWorkerJesus. I personally have a bit of doubt about this “free will” thing. See here.

“My father created the heavens and the earth. Not a sparrow falls that he does not see. He gifted all mankind with the gift of free will. Nonetheless it is still impossible to explain participatory appraisal methods without devolving into debates about PFIM and the like in the time between now and judgement day.”

Before leaving this section I’ll share a response that got my attention. In response to this obviously angry person I’ll gently say, “Yes, I do care to understand.”

“They don’t understand and probably don’t care to. AND, btw, neither do you, for asking such a fatuous, facile, fucking stupid question.”

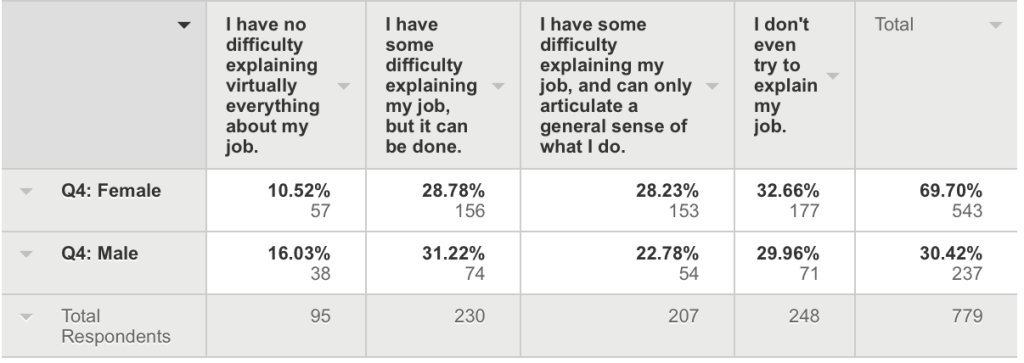

Significant others

Q35 looked at sharing with life partners and lovers asking, “Which statement below best describes your ability to explain to non-aid worker significant other the nature of your job?” Though many reported having the luxury of their partner also being an aid worker or in a similar job, many offered comments illustrating a range of understanding and acceptance. Of note is the fact that many used this comment space to point out that they were without a significant other. This respondent, methinks, speaks for many:

“Um, what if I don’t have a “significant other.” You bastards. Didn’t think of that did you? When I was dating aid workers (which happens) I didn’t have any trouble explaining ‘what I did’ but the relationships were so dysfunctional that explaining our jobs in tidy sentences was the least of our problems. I dream of dating somebody who knows nothing about what I do…” – male HQ worker

On the dating front, I saw this comment frequently in various wordings, “Since becoming an aid worker I have only dated aid workers, diplomats, military, or related. They all get it. I can’t really imagine having a significant other who has not been in such a sector.” – female expat aid worker

This respondent represents the views of many aid workers:

“Part of being an aid worker is not really understanding what ‘significant other’ means – or only dating in the sector – both of which being equally confusing. in the sector, it’s hard to detach from work – and it’s a relationship (vacationship or locationship) built around coordinating R&Rs and understanding each other’s acronyms. outside the sector it depends on how much of an interest he takes in my work – hopefully a good amount, but not always the case. more often than not it remains a mystery.” – female expat aid worker

These next posts illustrate a common “holding back” theme.

“My on again off again boyfriend thinks I do this job for the ego boost (I try to explain that I spend a fair amount of time hating myself and trying to un-see what I’ve seen). He wants me to quit…” –

“My partner worries about my exposure to danger, so I censor most of what I do.” — 31-35 yo male expat aid worker

And finally for comic (?) relief, here is the response given by AidWorkerJesus, “I’m not allowed to comment about my significant other, despite the allegations in certain racier pages of the non-canonical gospels.”

Children

Q37 drilled into the task of explaining the job to children asking, “Which statement below best describes your ability to explain to non-adult family members the nature of your job?” There were many who felt that it was impossible and/or inappropriate but also many who felt that children could sometimes understand more easily than adults in part because they were free of preconceptions.

The five posts below illustrate a common thread I have noticed throughout the narrative data. Aid workers are very sensitive to the fact that what they do is frequently misunderstood and reframed improperly in ethnocentric/Westerncentric terms.

- “Nieces/Nephews understand that I travel a lot to help people. I focus more on natural disasters (earthquakes, cyclones etc) to avoid explaining complex conflict (i.e. CAR) and to discourage sub-Saharan African bias.” – female HQ worker

- “Out of fear of instilling a “help the people with charity” mentality in my younger relatives, I just try to emphasize that people help themselves more than I help anyone.” -female HQ worker

- “Way too complicated. “Helping poor people in Africa” is about all my teenage nephews could compute, and I refuse to talk about my job in that way.” – female expat aid worker

- “Not sure they’re interested. I also don’t care to glamourise this work in case they feel it’s something that can get into through voluntourism.” – female expat aid worker

- “It’s easiest when I describe to people that we help governments in developing countries to support their Ministries in e.g. Health and Education perform better, collect data, deliver services, etc. Family can relate to Government Ministires doing real and important and complicated work. That way, it’s not about pencils and goats and they can undertand this isn’t little charity projects – it’s professional work and yes third world countries have functioning States like you do.” – female HQ worker

This next statement captures the same sentiment and expands on the ongoing challenge of aid workers to frame the social reality of their world in the most accurate and unbiased manner possible. Part of the task involves understanding and then working to change the ‘mental models’ of others.

“There are different mental models that we all have regarding interpretations of aid work and I find it difficult to relate to others’ mental models or bring people into my mental models. This prevents meaningful discussions or prevents moving past surface level conversations. This is exasperated by increased levels of idealism amongst youth that I find difficult to relate to.” – female expat aid worker

Other comments illustrate that some kids can understand more than some might think though some may not be ready for deeper appreciation.

“It’s easier to explain to kids that things are complicate because they haven’t yet formed opinions. They can manage complexity better than many adults.” – female expat aid worker

“It’s easier to explain to kids that things are complicate because they haven’t yet formed opinions. They can manage complexity better than many adults.” – female expat aid worker

“I think that when my niece, and inshallah my own kids, are older (10?12?) I will start to have some of those conversations. For the moment, at age 5, it’s all about Disney princesses. Maybe we should write to Disney and get them to make a film about aid work!” – female expat aid worker

“The easiest is to whip out my phone and say, ‘yeah look at the photo of that elephant, I took that. Now check this photo of a starving kid, I took that too, now eat your veggies.'” – male expat aid worker

The last respondent I’ll highlight raises a very critical question about who can handle the full truth. Most parents struggle with the issue of how long to preserve the age of innocence, and no parents are in a tougher situation than those like the woman below.

“I work a lot on gender violence issues and have a real difficulty addressing this with my children, especially with my daughter. I don’t want her to be aware of how dire the discrimination of women can be. I don’t want it to affect her identity.” – female expat aid worker

Concluding thoughts

One takeaway from this section of the survey is that being an aid worker is complicated, both the actual job be perhaps even more so sharing of the details of the job. Sharing the life and death intensity, the stark, raw reality of some of what is experienced can feel wrong at times, putting some memories into words can seem incomplete. No description regardless of the verbal skills of the aid worker can do full justice to the complex nuances of sights, sounds, smells, and emotional highs and lows. In the words of one respondent, “You would have to experience the fear and hopelessness first hand to get the whole picture.”

so sharing of the details of the job. Sharing the life and death intensity, the stark, raw reality of some of what is experienced can feel wrong at times, putting some memories into words can seem incomplete. No description regardless of the verbal skills of the aid worker can do full justice to the complex nuances of sights, sounds, smells, and emotional highs and lows. In the words of one respondent, “You would have to experience the fear and hopelessness first hand to get the whole picture.”

Another respondent noted, “That is one of the main problems we have. After being away for years your mentality, values and personality changes. You disconnect from your old habitual community and then it is difficult to communicate as we ended up on two different planets: usually I am not interested what they tell me because the topics they touch are not interesting to me and other way round.” -36-40 yo male expat aid worker

Transforming an experience with innumerable dimensions into words -necessarily a linear description- means destroying -and hence disrespecting- some of the content. There are some details which cannot and perhaps should not be shared with outsiders. You had to be there or, at least, have been somewhere similar, and that means with those who you’ve lived with in the team house or other aid workers, in the same ‘compartment.’

As a final though, I was struck, yet again, by the thought and care put into many responses. If you are one of those 1010 who responded to our survey, thanks again. You continue to help us shed light on your world.

As always, contact me with feedback on this or any post.

Post script

Here are some questions that went though my mind as looked at the many hundreds of narrative responses to our three open-ended questions asking about how people explain their job to those outside of the sector:

- When the situation calls for it, how do aid workers explain their job to friends, lovers, family and children in their lives?

- Is the need to explain based mainly on affective/emotional needs or are there purely instrumental reasons for disclosing?

- To what degree do the preconceptions people have about the aid work sector impact the ability to explain their job?

- To what degree is the aid work job too complicated to explain effectively?

- To what degree does the nature of aid work impact the tendency for aid workers to compartmentalize their lives?

Follow

Follow