On this World Refugee Day 2022 let us not forget that all refugees have a right to an education

Listen to a poet

As a sociologist I am fully aware of how complex social reality is. In this ever globalizing world where cultural histories are now blending together, the task of capturing all the detailed nuance of one’s life is a daunting undertaking. Poetry is a time honored tool women and men from all over the world have used to artfully articulate observations about their lives and about the culture(s) in which they live and act. Poets are lay sociologists using an alternate language structure to share powerful insights. My goal with this essay is to comment on education as a basic human right and I can think of no better way to start than to use poetry.

Below are two poems by Rohingya refugee Roshidullah Kyaw Naing, soon to be published by Notion Press Publishing [printed with author’s permission]. I have been asked to write the Foreword to his book entitled The Painful Life of Rohingya. I think his words are a powerful testament to why education is necessary for all.

Education For All

Education should be given to all

Education is important for all

It belongs to every humans

It’s fundamental human right

Education is important in human lives

It is the key to be successful in life

Without it life is darker

Give first priority in education

Peace through education

It can make you vigorous

It can help you to identify things

It can show you

To communicate with each other

It can help you to visit around the world

It can keep you on right way

It can keep you healthy

Never forget to learn

Education in your life

It’s the most powerful in the world

It’s the backbone of the world

Value Of Education

Education is a hand-light of the life

Without it the world is blind and dark

Try to be educated so that you can make

The whole world bright with your light.

The rights of refugees

According to the UNHCR, across the globe there are more than 84 million forcibly displaced people, 35 million (42%) of which are children. 26.4 million of those displaced are refugees. It is estimated that 6.4 million of these refugees live in refugee camps, over two-thirds (4.5 million) living in planned and managed camps, while the rest (2 million) are sheltered in self-settled camps (UNHCR).

Humanitarian resources devoted to caring for refugees in UN sanctioned camps are critical in maintaining a safe and healthy environment. In many cases the time spent in a refugee camp can typically be measured in years and, in some cases, even decades. This is the situation of many Rohingya refugees now in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, some of which arrived last century.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol represent the foundation of international law related to refugees. Those recognized by the UNHCR as having refugee status have many rights, perhaps the most important of which is non-refouelment. Under international human rights law refoulement refers to

“…any form of removal or transfer of persons, regardless of their status, where there are substantial grounds for believing that the returnee would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return on account of torture, ill-treatment or other serious breaches of human rights obligations.”

A second critical right of all refugees is the right to education, especially in early childhood. Of refugee children under the UN’s care, roughly 48% remain out of school due to many factors, not the least of which is chronic underfunding. The most recent estimate puts the funding gap at 52%, and to say humanitarian resources are stretched is a gross

understatement.

Education is a basic human right as stated in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1951 Refugee Convention and updated in the 1989 Convention on the Right of the Child, with the goals of protecting, empowering, and enlightening refugee children.

Over time and in various contexts there have been different interpretations and approaches concerning education at the humanitarian level. The 2018 Global Compact on Refugees and the 2030 Agenda frames education’s goal to “enable them [refugees] to learn, thrive, and develop their potential, build individuals and collective resilience and contribute to peaceful coexistence and civil society” (UNHCR 2019). Though Bangladesh, the temporary home for approximately 1 million displaced Rohingya, is not a signator of the 1951 Refugee Convention, various judicial rulings have implied broad acceptance of varying degrees on several key elements.

Here is Article 26 from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Article 26

Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory.

Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

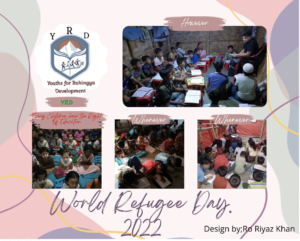

World Refugee Day 2022

The theme for World Refugee Day 2022 is the right to seek safety. Becoming a refugee is a horrible forced choice taken as a last resort by people no longer safe in their homeland. Once becoming a refugee the immediate goal is safety and security. The main longer term goal, however, is repatriation, going back to their previous lives and homes but now free from danger. This dream of repatriation remains strong in the vast majority of refugees but its fulfillment is delayed, sometimes by years and even decades. The need for some level of a normal life is strong, and an educational system, especially for younger children who crave order and routine, is an essential part of that normalcy. For the older children and young adults resuming educational opportunities is a pathway toward a better future both individually and for their community.

‘Robbed generation’

Gertrude Stein is credited with coining the term ‘lost generation’, first used to describe those disoriented by the social upheaval of World War I. The term ‘stolen generation’ refers to the First Nation peoples in Australia who were taken by government officials from caring and able parents as an effort at ‘assimilation.’

What do we call the

countless children who have grown up in refugee camps, denied a normal cultural life and oftentimes lacking access to primary, secondary, and tertiary educational opportunities? ‘Culturally robbed generation’ may be accurate, if not as pity as the other two examples. In any case, the fundamental right to have a coherent cultural life with dignity is surely taken from those in refugee camps, so using the phrase ‘robbed generation’ seems accurate.

My personal connection

For me teaching sociology has always been a humanitarian act in the fundamental sense of that word. The ‘critical Hydra theory’ I have been using in my teaching the last several years explicitly emphasizes ‘respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms of all humans,’ especially those who have been historically marginalized. During my long career in all my classes I have sought to promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups and have even been more inclusive by encouraging the understanding of human diversity in all its many manifestations. In the last year I have been fortunate to partner with staff from the Centre for Peace and Justice in Bangladesh and have helped conduct two very successful online classes for Rohingya and Bangladeshi learners. Our hope is that in the future all youth everywhere will have access to appropriate educational opportunities.

As I lifelong educator I have devoted my entire career to helping shape the minds of young people. I am devoted to education because I have seen the impact the classroom experience can have both on the individual and on her/his larger community. The impacts I have seen here in the United States are the very same I have seen in Bangladesh; the importance and impact of education crosses all cultural barriers.

The impact of education

We know from various sources of data that,

- Education has many outcomes, and one obvious and important outcome is the actual content including learning to read, write, and acquire basic numeracy skills. But more importantly, being in a classroom gives learners a purpose and a future. It gives them a sense of hope and the possibility of progress and growth not just physically but intellectually, spiritually, and emotionally as well.

- Education, especially as presented the critical thinking as a major focus, is one of the main forces capable of neutralizing all of the privileging forces faced by many learners.

- Education is a radical feminist act. We know from various sources of data that young girls who attend school are empowered on many levels. SGVB is lower among educated females not just in refugee camps but in all settings and cultures.

- Children who regularly attend school are far less likely to engage in destructive and delinquent behavior that makes them easy prey for those who would exploit them.

- Children who regularly attend school are more disciplined, and have higher self esteem compared to those who do not attend school.

- Education, especially secondary and tertiary education, is critical for developing and maintaining community cohesion.

- Education, especially secondary and tertiary education, is critical for nurturing leaders equipped to listen carefully and thoughtfully to those around them and to respond to the needs of their communities. Critical thinking skills are essential for visionary and effective leaders.

- One main tool of those who seek dominance over a population, especially those who rule with an authoritarian hand, is to deny access to education. An educated population has, metaphorically, a strong immune system, able to fight off ‘infections’ like corruption and false consciousness which can lead to an acceptance of the ideas that they are inferior, less human, and less deserving than their oppressors. An educated population is more resilient and able to understand the social forces that impact their lives, becoming better able to act as their own advocates.

- An educated population has a common ‘language’ with which to communicated both internally among themselves and externally with, in the example of refugees, the humanitarian and government actors with which they must interact.

Teaching in prison

Early in my career I taught both in a women’s prison and also in a holding facility for incarcerated juveniles. My friends, family, and sometimes colleagues asked about the meaning and value of education in these contexts. As I reflected on this question I looked into my past for an answer. Coming from an extremely poor family, I never saw myself as above anyone else (quite the opposite), and the weltanschauung I developed as a young boy has had a lifelong impact on my pedagogy. Though I am certain at times I have failed, I have approached every class as a meeting of equals and have made consistant efforts to respect and value every learner in every context. I invite my learners to think with me and with each other, embracing the conceptual tools of my disciple to understand themselves and the world around them at a deeper level. I share my commitment to critical thinking and warn them that this approach to learning causes one to question themselves and the culture in which they live and act.

More thoughts on refugee education

I continue to learn more about the realities of refugee life through reading poetry written by refugees, my teaching experiences, and through countless conversations with refugees and those who work with refugees. Below are some brief points, any one of which merits a more detailed discussion. [Note: What appears above and below are some of the talking points I will use as a guest for a Webinar on refugee education to be held in late June.]

One major question is funding for any educational structures for refugees. This question cannot be separated from the issue of how refugee populations put stress on the cultural, social, economic, and political fabric of their host communities. The dynamic of this question changes in the two fundamentally different types of hosting. By sheer numbers, the more common model is where the refugee population is absorbed into the host community such as is the case of many Palestinian and Syrian refugees working in and around Amman, Jordan or Kurdish and Syrian refugees in and around Erbil, Iraq. The second model, and the one with which I have the most personal knowledge, is where refugees are gathered in what are effectively open-air prison camps, their rights -most dramatically their right to move about- being dramatically curtailed.

In the most common model, the cost of education must be largely absorbed by the host communities thus making scarce resources such as classroom space and qualified teachers spread even more thinly.

In the refugee camp model the cost of education is borne by the international humanitarian system overseen by the UNHCR with outsourcing to INGOs like World Vision, Save the Children, and the Danish Refugee Council.

In both models, the cooperation of and permission from the host government (and relevant Ministries) is necessary and can sometimes be contentious. At issue are many factors, the most obvious of which is the economic impact.

Although at least some level of primary education is almost universally accomplished in both settings, secondary and tertiary education opportunities are severely limited, especially so for females. The humanitarian sector is chronically underfunded and whatever limited resources are available are allocated to the most pressing needs of the refugees with education -especially anything beyond primary school- almost always being at the end of the funding queue.

Given that many refugees remain in contained camps for 10+ years, one main negative consequence of having education be such a low priority is, as mentioned above, that there are ‘robbed generations’ of children never having had the chance to receive any formal education beyond the first few years. That said, everyone, especially the young, are sponges of information from the media, especially social media. These sources of passive education are highly questionable in their value and are prone to bias and creating a skewed world view. Social media is no replacement for a thoughtful liberal arts-type curriculum where critical thinking skills are learned and honed. Not so with a ‘media’ education.

In my opinion education for refugees cannot and should not be limited to solely Quran-focused madrasas, but rather should be focused on core academic skills and perhaps vocational training. Critical thinking must be free from dogma. There is a need for any curricula used for refugees to be culturally sensitive. In my experience there is a fine line, for example, between respecting cultural practices and condoning overt misogynistic policies and practices, especially in contexts where the refugee population adheres to fundamentalist religious practices. To be specific, in the critical Hydra model that I use in my classes, two of the eight ‘privileging forces’ heads of the Hydra are patriarchy and hetero/cisnormativity. That both of these privileging forces are supported by much fundamentalist dogma can create a challenging classroom situation.

Learning from Pedagogy of the Oppressed

My views on the purpose and pedagogical approach that should be taken in the classroom are informed by and most closely align with the sentiments found in Paulo Frire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. According to Frire, the central focus of any educational experience, especially of those most commonly marginalized, is to have the educator and the learners join hands in an effort to humanize themselves and to address the very process of oppression. Addressing and then effectively neutralizing the issue of power differences within the classroom is essential, and accomplishing this goal helps address power issues in the larger sociocultural context. No easy task, that.

It is very likely that Frire heard the words of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara who said “I am not a liberator. Liberators don’t exist. The people liberate themselves”. As an educator from the Global North I make efforts to fully understand my positionality and to constantly work to move beyond the false messages that my cultural indoctrination provided to me regarding all aspects of human diversity. My interaction with marginalized learners is not an act of ‘saviourism’ but rather a humanitarian partnership to expose oppression at all levels.

One tool that can be used is to have a learner based model. Not students, but rather learners, including and emphasizing a two way, non-hierarchical learning process.

The gap between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’

There is a constant and even epic struggle between what our aspirational documents (the quintessential example of which is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) advocate and what, given practical and political realities, is being accomplished regarding all social justice issues. Sociologists use the terms ‘ideal culture’ and ‘real culture’ to make this distinction, with ‘ideal culture’ reflected in our mission statements and constitutions and ‘real culture’ the actual state of human affairs. Indeed, much social justice work can be seen as efforts to close the gap between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’. Assuring the right to education is clearly no exception.

Providing education for refugees is one dimension of fulfilling the humanitarian imperative, the enactment of which is guided by core principles. The humanitarian principles have historically been listed as humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. Expanding on the principle of impartiality, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) states,

“Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.”

Regarding the principle of independence they say,

“Humanitarian action must be autonomous from the political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold with regard to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented.”

Adhering to these principles, especially impartiality and independence, is more aspirational than practical; humanitarian efforts are always complex and any actions taken -or, for that matter, not taken- are deeply impacted by both international geopolitics and the regional/national political realities. Providing education to refugees though a seemingly neutral humanitarian act can become very political on many levels.

One need only look at the situation in Bangladesh and the controversies surrounding education within the sprawling Rohingya refugee camps near Cox’s Bazar. Not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Bangladeshi government avoids the word ‘refugee’ referring rather to “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals” (FDMN). Since the UN and INGO entities that would provide education in the camps are there at the invitation of the Bangladeshi government and can be ‘disinvited’ if they do not follow Bangladeshi government policy, education in the camps has become inherently and increasingly challenging as the humanitarian actors walk a delicate balance between the principled and the practical.

In an attempt to provide educational opportunities, an Orwellian-esque game of chess is currently being played where NGOs and INGOs label some education focused activities using language that avoids being red flagged by the Bangladeshi government.

As a side note, several years ago I worked on a documentary describing the educational efforts of the EZLN, the ‘Zapatistas’, in Chiapas, Mexico. The main focus of the documentary was on a group of Elon University students who had partnered with the Zapatistas and helped paint a small school near Oventic. The title of the documentary was Painting Without Permission. Those of us making efforts to provide educational opportunities within the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar could be described as ‘teaching without permission.’

Final note

If you have made your way through all of the above, kudos to you! This post is a ‘brain dump’ of reflections related to the basic human right to education, specifically as it relates to the nearly 1 million refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. I beg you patience and your comments. Feedback can be sent to arcaro@elon.edu.

Follow

Follow