[Minor updates 6-10-23]

“My words are taller than the walls put between Buddhists and Muslims. My words are stronger than the hatred designed for me…My words build bridges between ethnic communities. My words fight against injustice and ignorance. My words have no religion. My words are for humanity. My words know no borders. My words are for peace and harmony.”

-from the poem My Words by Rohingya refugee, Mayyu Ali

“Humanity is the only true nation.”

-Paul Farmer, co-founder of Partners in Health

“Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…”

-Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

A measure of our humanity

According the the UNHCR there are over 70 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. About double that number, over 140 million, currently are in need of humanitarian protection or assistance. If all of these people were a nation, it would be the 10th most populous in the world. How we respond to those in need is a measure of our humanity, and the humanitarian workforce is on the front lines of this response.

As a college professor teaching a class about ‘global social problems’, it is my job to learn about the challenges that face humanity and to help my students understand these issues. The global issues are many, ugly, complicated, and contentious, and it is at times difficult to remain optimistic.

Hearing positive stories is always welcome, and when I learned about the recent “Poetry for Humanity” event in Yangon, Myanmar, I felt a glimmer of hope. This three day event, sponsored in part by the ATHAN Freedom of Expression Activist Organization, is described here in a news article,

“Divided by hatred but united over the written word, Rohingya Muslim poets in Bangladeshi refugee camps joined Buddhist bards in Myanmar by video link as part of a groundbreaking poetry festival in a country reeling from genocide allegations.”

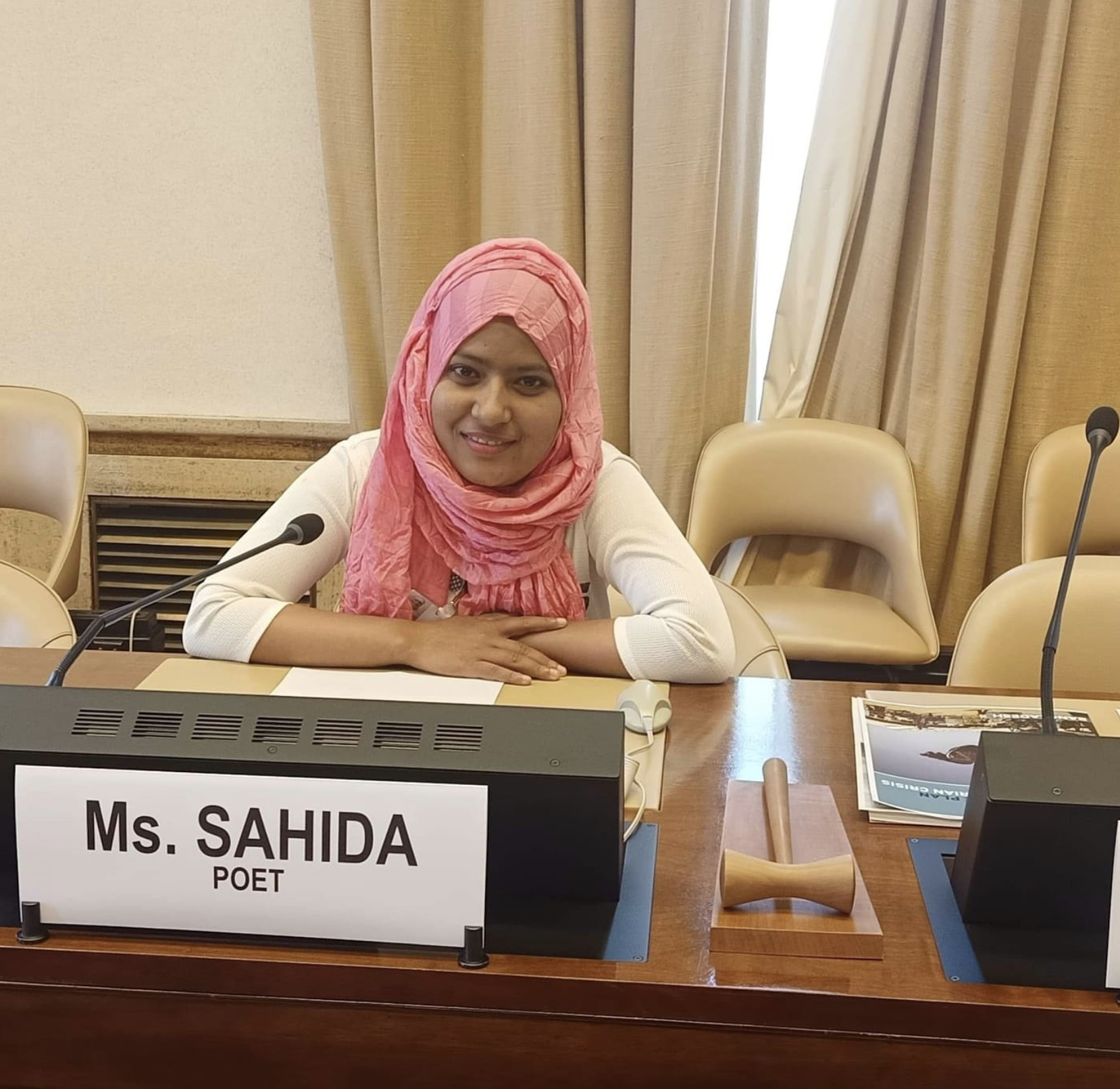

Over the last many months I have gotten to know two of the five Rohingya poets that presented at this event, Mayyu Ali and Shahida Win. Shahida’s poem “Unforgettable Dark Past” is powerful, describing the horror of genocide.

Here are some key lines from Mayyu Ali’s poem “My Words”:

“My words build bridges between ethnic communities.

My words fight against injustice and ignorance.

My words have no religion.

My words are for humanity.

My words know no borders.

My words are for peace and harmony.”

His words articulate an inclusive and humanistic vision, reflecting and echoing the sentiments of both Paul Farmer and the United Nations: we are one human family, with every human possessing “inherent dignity and … equal and inalienable rights.”

The lie of civilization

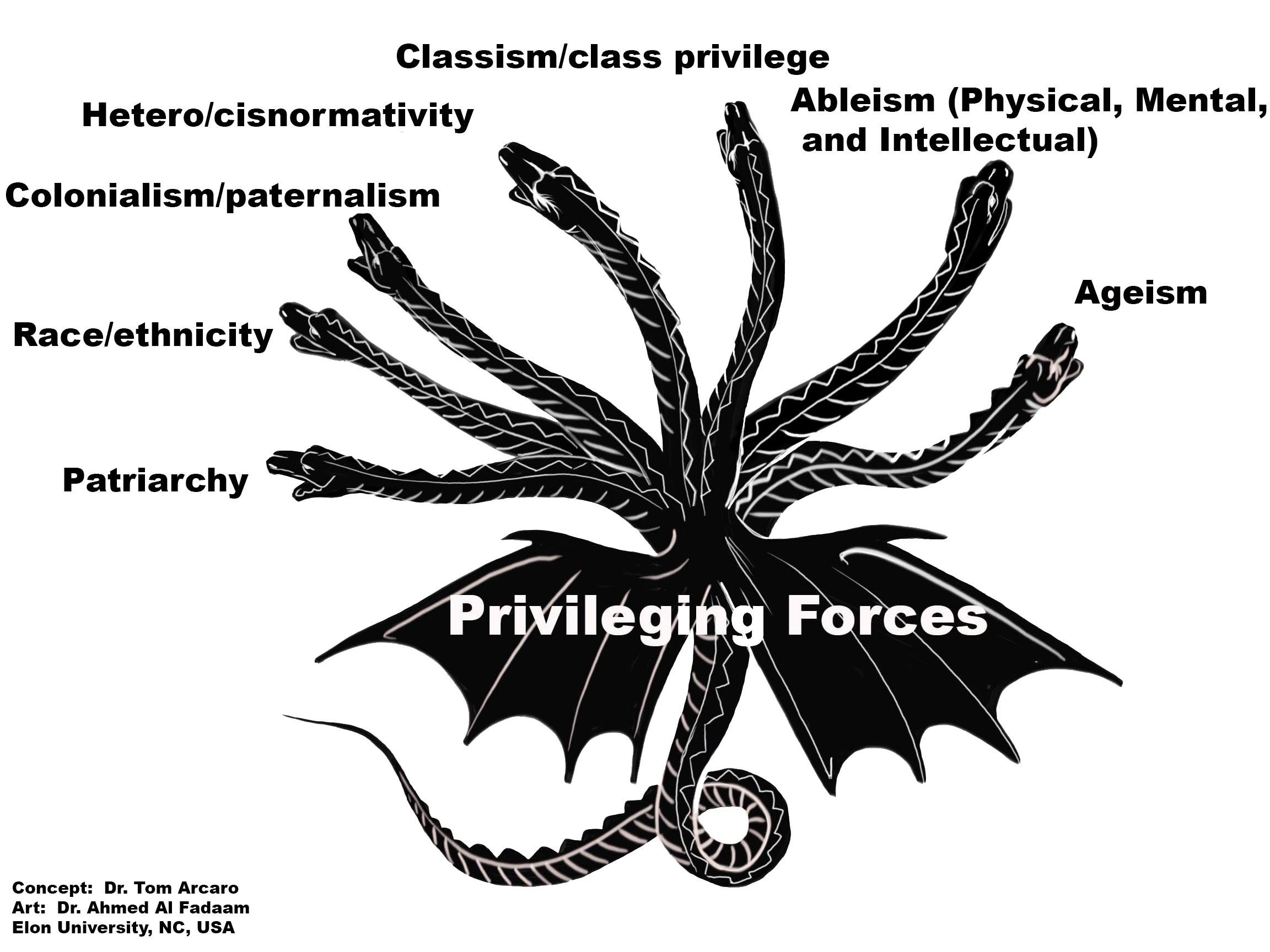

We cannot change human nature, but as one human family we can -and must- use our collective wisdom to work toward creating and sustaining social, political, and cultural systems (including laws, policies, customs, school curricula, and so on) which tamp down our more destructive and selfish urges.1 The toxic othering which feeds the Hydra must constantly and persistently be addressed on a multitude of levels, both structural and individual.

Examples of actions that have already taken been taken include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the establishment of the legal wing of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice. More acts are needed at both the international and nation levels, and, perhaps most importantly, at the local level.

The lie of civilization is that we are not. We are not civilized. Our global community is all too full of examples of grossly uncivil behavior. Although there continue to be loud voices chanting ‘never again‘ in response to the Holocaust last century in Europe, our global community watches right now as at least two acts with every appearance of genocide take place, one in Myanmar and the other in China. I must also point out that examples of truly uncivil acts are far too easy to find in my own nation, the United States.

The words of sociologist Theordor Adorno fit here,

‘“It would be advisable to think of progress in the crudest, most basic terms: that no one should go hungry anymore, that there should be no more torture, no more Auschwitz [or Gaza or Cox’s Bazar]. Only then will the idea of progress be free from lies.”

I have confidence that Adorno would be happy to modify the last sentence to read, ‘Only then will the idea of civilization be free from lies.’

One issue faced by humanity is that globalization is propelled forward by the algorithm of capitalism which inexorably amplifies and then feeds on our insecurities and on our fear of being judged by those around us.

inexorably amplifies and then feeds on our insecurities and on our fear of being judged by those around us.

We must work toward a world which does not normalize and glorify our baser tendencies such as hatred, greed, gluttony, and pride, and this means confronting the parallel Hydra of capitalism. We live in a world where there is no check on extreme wealth, with obscene pooling of money into fewer and fewer hands. We tend to confuse material and technological progress with becoming more ‘highly civilized’. I argue that to be truly civilized humanity must insure pathways to dignity for everyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity, class, age, ability, and any other ‘toxic othering’ status markers.

Here are the wise (and perhaps with a note of sarcasm) words of an indigenous person commenting about money and more,

“Before our white brothers arrived to make us civilized men, we didn’t have any kind of prison. Because of this, we had no delinquents. We had no locks nor keys and therefore among us there were no thieves. When someone was so poor that he couldn’t afford a horse, a tent or a blanket, he would, in that case, receive it all as a gift. We were too uncivilized to give great importance to private property. We didn’t know any kind of money and consequently, the value of a human being was not determined by his wealth. We had no written laws laid down, no lawyers, no politicians, therefore we were not able to cheat and swindle one another. We were really in bad shape before the white men arrived and I don’t know how to explain how we were able to manage without these fundamental things that (so they tell us) are so necessary for a civilized society.”

― Lame Deer

Good news on the eve of the ‘Poetry for Humanity’ event

On 23 January 2020 the International Court of Justice (IJC) issued this statement, informing Myanmar that it must take immediate measures to protect ethnic Rohingya against genocide. A final decision on the case brought by The Gambia against Myanmar on the change of genocide may not come for months or even years, but this recent ruling by the IJC was seen as a victory by many refugees now living in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

As this good news came out, Rohingya families in Cox’s Bazar crowded around televisions, smart phones, and computers. The response to the news from the IJC was relief, joy and a sense of affirmation. The world had heard their cries which had been captured so graphically in the poem Shahida Win read via Skype to those gathered in Yangon for the “Poetry for Humanity” event. Here are a few lines from her poem,

“And slaughtered all of Rohingya like animals

Corpses in streaming blood

Criminals looted our properties

Set fire villagers to ash

The sight of burning we contacted

Heart-wrenching, difficult to forget

The lusted rapist armies

Gang raped Rohingya minor girls

Their screaming for help still echoing across Arakan’s sky

Yet reflecting into ears, difficult to forget”

Confronting the lie of civilization

Shahida and Mayyu are confronting the lie of civilization through the simple yet powerful act of writing poems. The IJC is confronting the lie of civilization by affirming that genocide is wrong and must be stopped. These two forces, refugee poets and international courts, the quintessentially local and global, are working toward the same goal and represent what is best about humanity. They are working for a more civil world where each life holds equal value.

As we continue to imagine and then enact ways to confront the many ‘privileging forces’ of the Hydra let us be inspired by the words of poets.

As we continue to imagine and then enact ways to confront the many ‘privileging forces’ of the Hydra let us be inspired by the words of poets.

Again, listen to Mayyu:

“My words are taller than the walls put between Buddhists and Muslims. My words are stronger than the hatred designed for me.”

Please contact me if you have any feedback, comments, or questions.

1This is the central message of Erich Fromm’s 1955 book The Sane Society

Follow

Follow