“When you are 20, you want to change the world but you accept that it’s going to take maybe five years. When you are 25, you decide you just don’t want to make the world any worse through your profession, buying choices, politics etc. When you get to 30+, you realise ‘Fucking hell, it’s way more complicated than anyone can possibly get their head around’.”

–30something female expat aid worker

“I don’t think we can change the world – just make it a bit better for a few individuals.”

–40something female HQ worker

Castles in the sand? Responding as we must, but…

Castles in the sand 1.0

This is not an easy post to write in large part because I am the director of a program the purpose of which is to work with cohorts of students as they learn how to make sustainable change around the world through meaningful global partnerships, i.e., development work. It is also not easy because I remain unconvinced of my own arguments.

First, two opposing viewpoints, one from a founder of sociology and other other from a politician with a flair for rhetoric and, not coincidentally, the founder of the Peace Corps.

“. . . numerous survivals of the anthropocentric bias still remain and here [in sociology], as elsewhere, they bar the way to science. It dis-pleases man to renounce the unlimited power over the social order he has so long attributed to himself; and on the other hand, it seems to him that, if collective forces really exist, he is necessarily obliged to submit to them without being able to modify them. This makes him inclined to deny their existence. In vain have repeated experiences taught him that this omnipotence, the illusion of which he complacently entertains, has always been a cause of weakness in him; that his power over things really began only when he recognized that they have a nature of their own, and resigned himself to learning this nature from them. Rejected by all other sciences, this deplorable prejudice stubbornly maintains itself in sociology. Nothing is more urgent than to liberate our science from it, and this is the principal purpose of our efforts.” — Emile Durkheim (quoted in “Man’s Control Over Civilization, An Anthropocentric Illusion“, pg. 330, The Science of Culture)

“Our problems are manmade–therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable–and we believe they can do it again.” –– John F. Kennedy, Commencement Address at American University, June 10, 1963

The Durkheim statement warns of the anthropocentric illusion of ‘man’s control over civilization’ and, in contrast, Kennedy says we are masters of our fate and can mold the social world as we desire if we have the political will and resources.

So who is right?

What of the anthropocentric illusion?

What of the anthropocentric illusion?

We must continue to build castles in the sand -act on our conviction that we can change the world- because, as Leslie White told us long ago, we must. This is part of what being human means. As one aid worker put it, “There will always be disasters, there will always be poverty and there will always be some people who feel impelled to try and make a difference.”

To be more direct, we must ‘fight the fight’ of responding to the myriad hot spots of human suffering and injustice around the globe be they in Biafra then or Syria right now. To do less is against not just our better nature, it is against our very human nature. One prototype model for this type of response is Herni Dunant (he of the killing fields at Solerfino), but there were many before him and since that personified this inevitable playing out of our basic human nature.

One aid worker put it this way:

“If I didn’t believe the above [that aid and development work are making a net positive change overall] I couldn’t continue working doing what we do. Someone I recently spoke with suggested that the world would be better if no aid was given anywhere to anyone, and whilst I agree that it is often a hindrance to development and helps certain negative situation perpetuate (war, etc), I found myself passionately defending it, as I truly believe that we have a moral obligation to help others in need of support, whether that is at home or overseas.” (emphasis added)

Evolutionary psychologists have reinforced my argument by providing evidence for a fairness module in our brain that, combined with an evolutionary tendency -most would say imperative- for empathy and, more generally stated, morality, we must respond to the suffering of others, especially that which we feel has been unfairly meted out either by natural disaster or human action (or inaction, if that is the case).

What Durkheim in the above quotation offers to us is a view some may argue is dismal at best and at worst a self-fulfilling-prophecy that will doom us to inaction or alternatively raw, selfish hedonism. But those arguments fly in the face of what we know about human nature. We must act as we are: a moral animal.

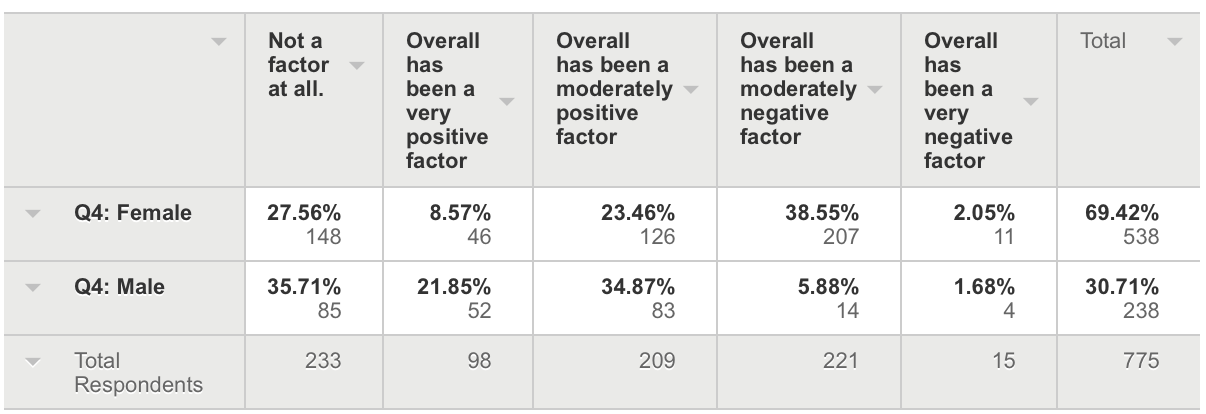

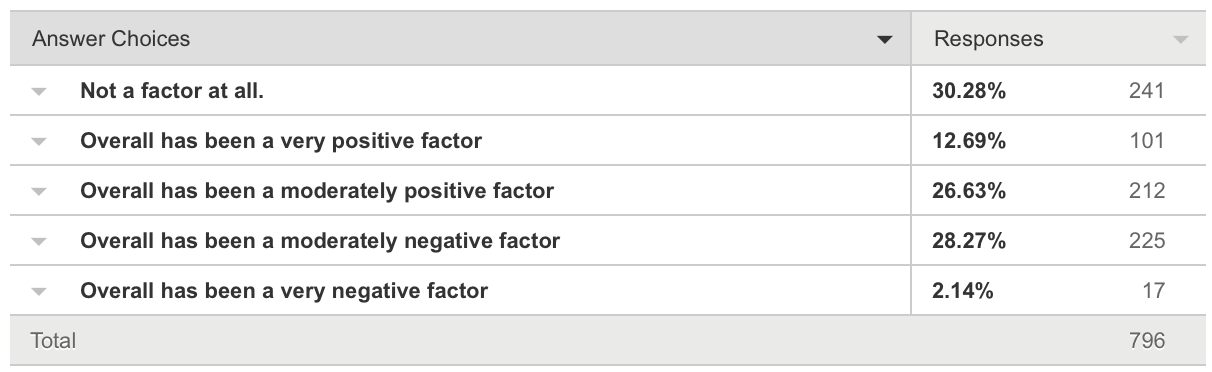

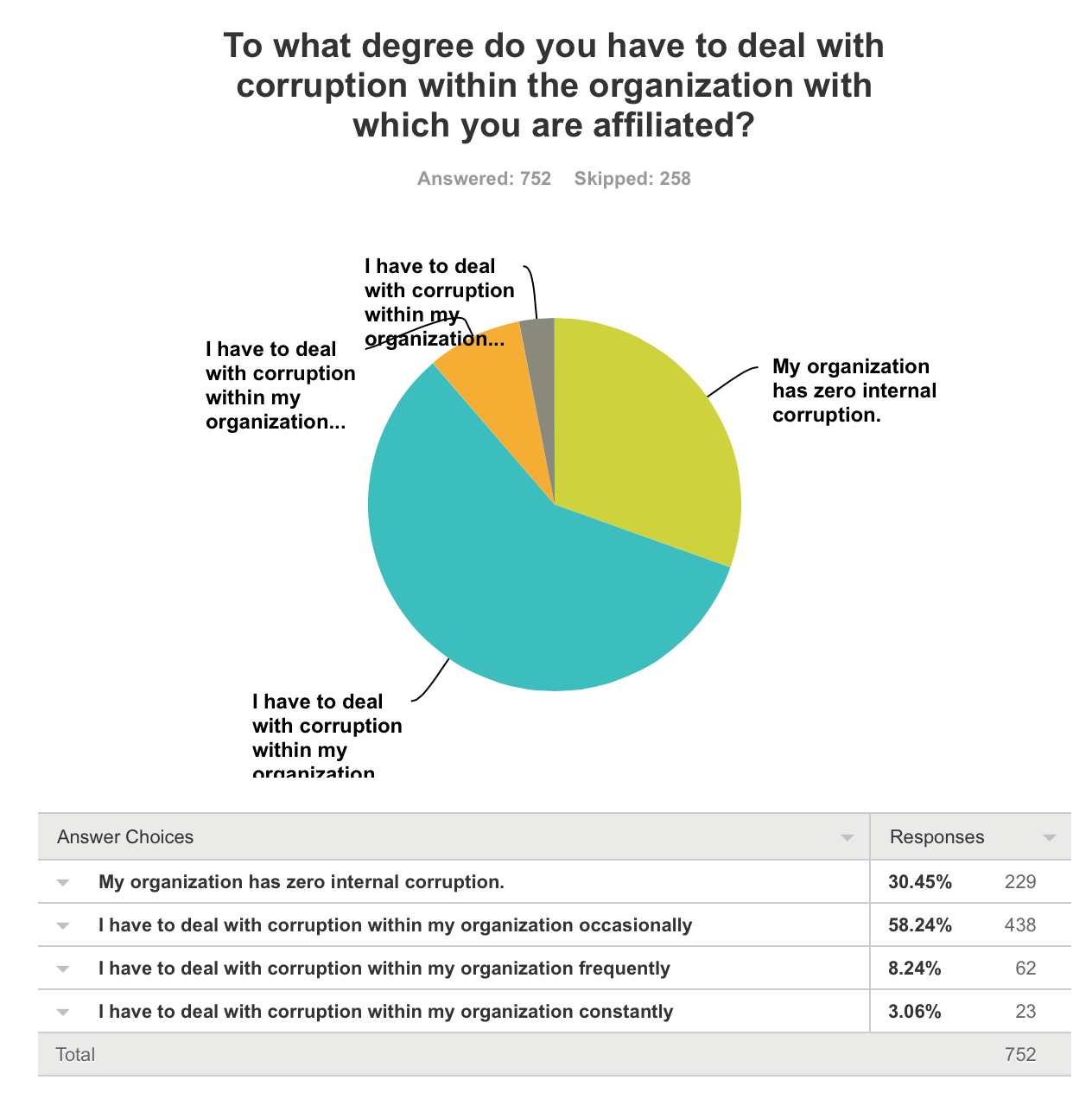

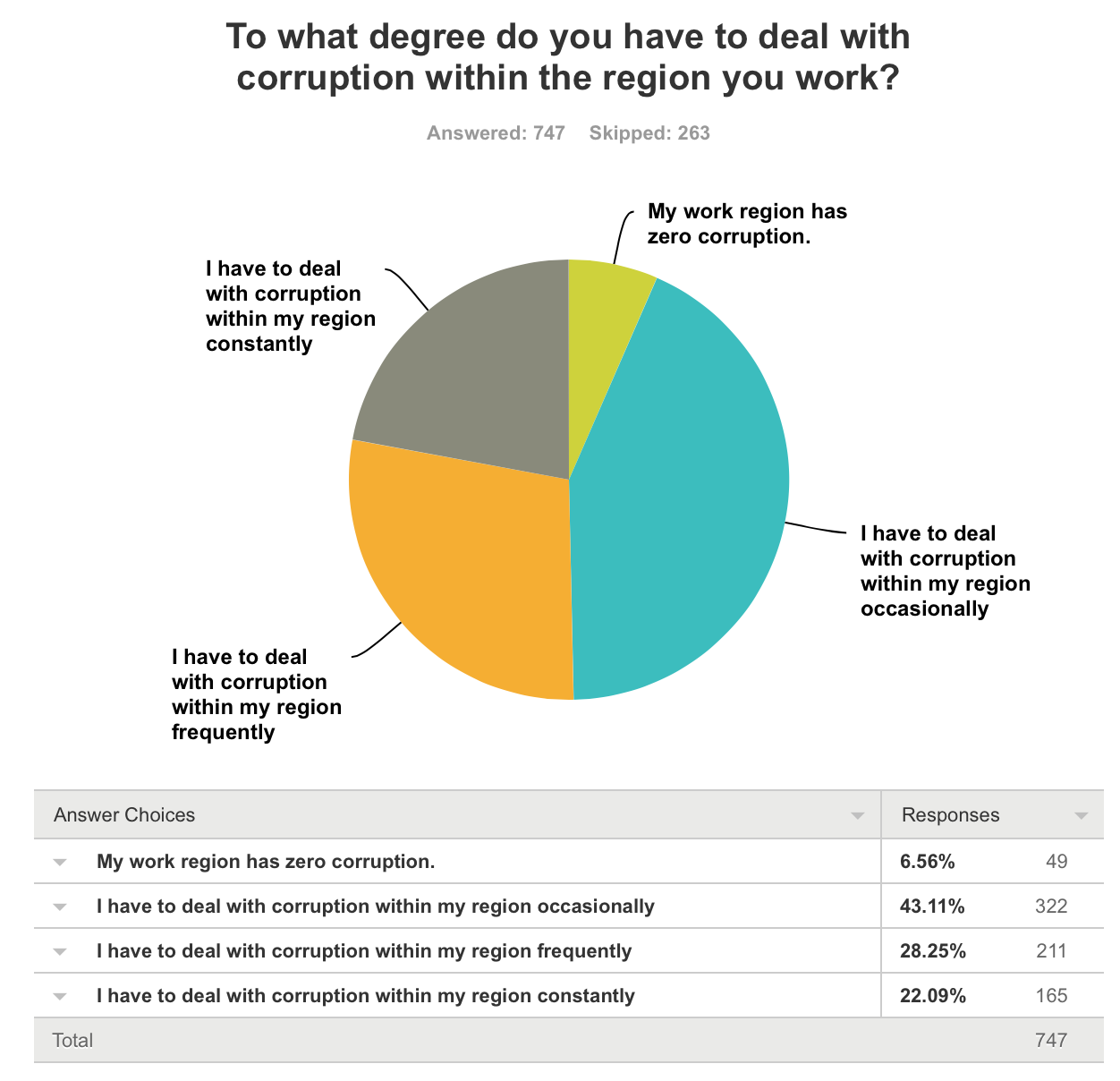

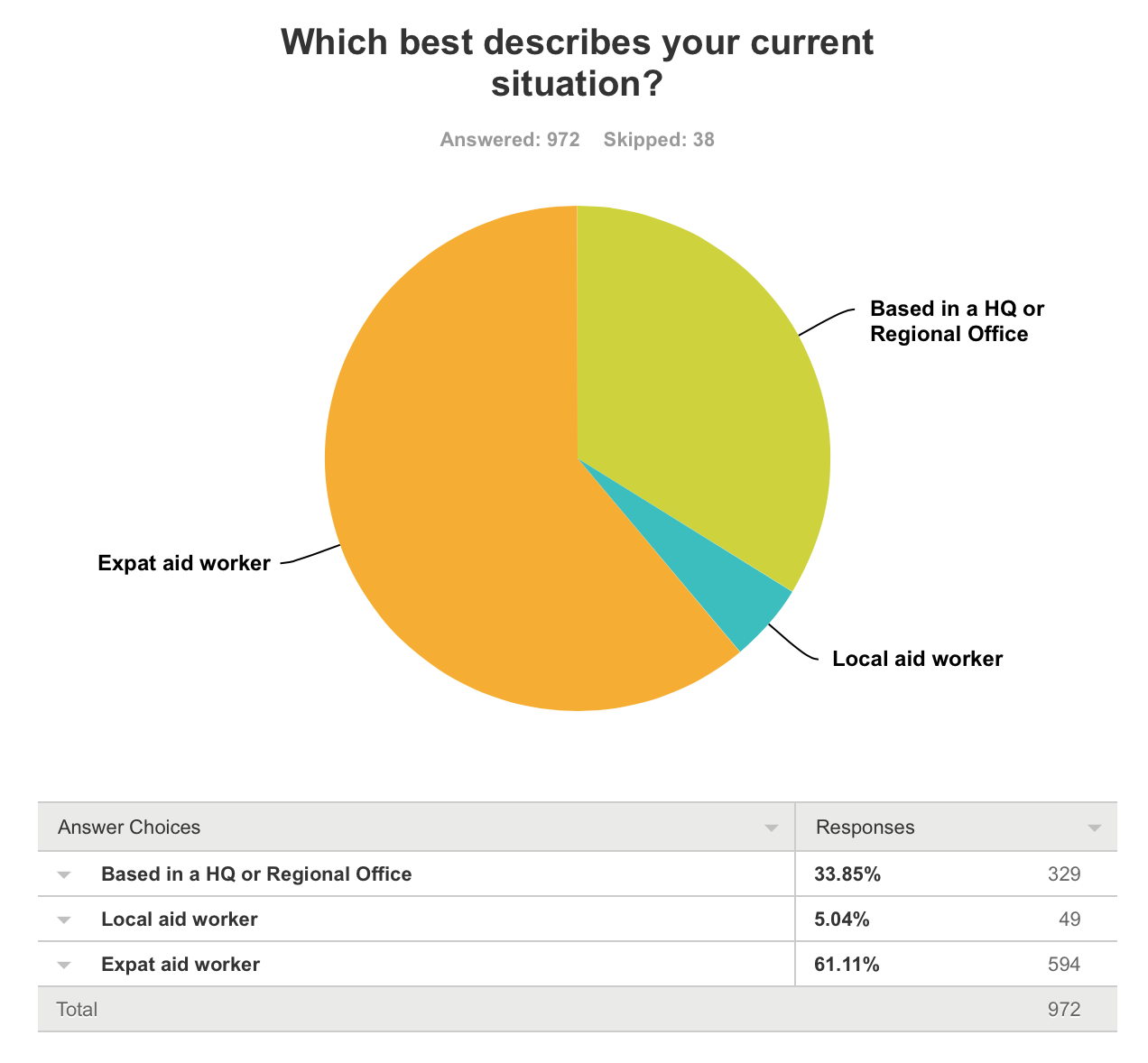

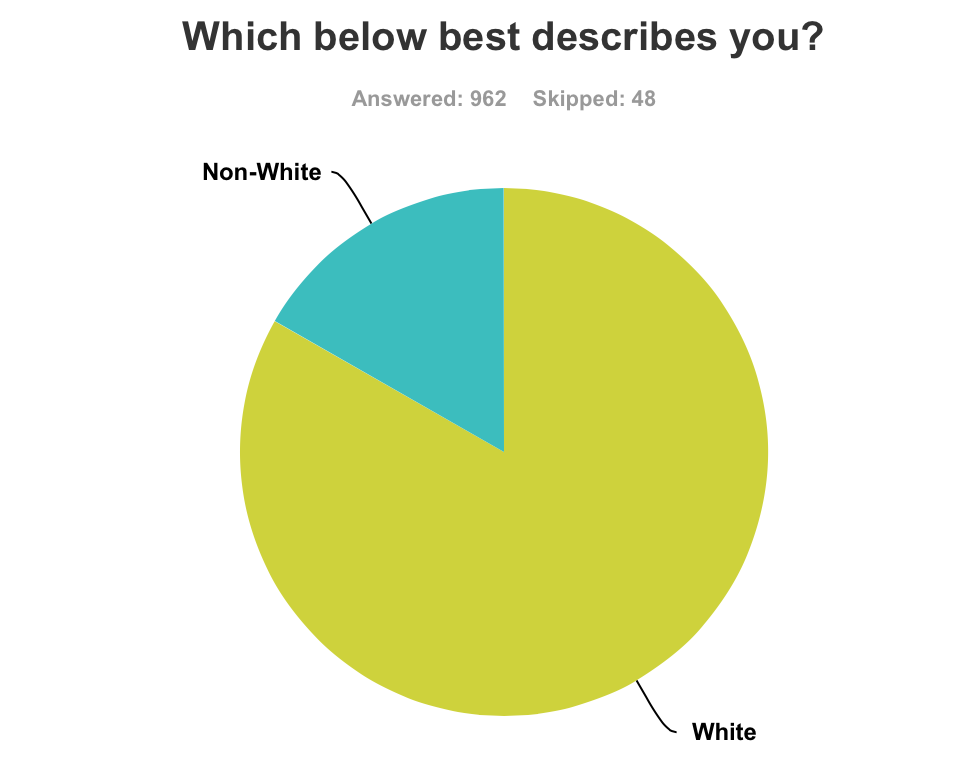

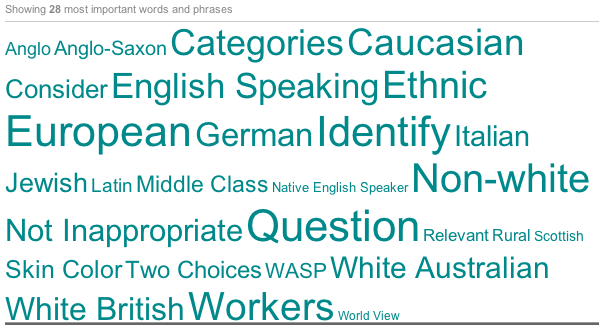

So, what does all this have to do with what our survey respondents said about the future of humanitarian aid? Here they are in the aggregate in response to Q59, Which statement below best describes your views about the overall direction of humanitarian aid work:

Even accounting for the design-challenged wording of the response choices offered, there is a visible, and I would argue both significant and sober, minority of respondents (10.16%) who might agree more with Durkheim than with Kennedy.

Why are they even in this field of work, you might ask, if they feel their efforts will have “minimal impact” on the lives of people? This is a good question, but one answer might be what I have pointed out above: it is who we are as humans. Many human traits appear in populations (for example, height) as a normal curve, most (68% in a true ‘normal’ curve) appearing within one standard deviation from the norm. But there are always those who are two and even three standard deviations from the norm on both ends. Humanitarian aid workers may be one manifestation of the natural distribution of the innate human need to seek fairness, show empathy and act, well, humanely. They exist clustered more on one end of the normal curve and, perhaps, spend their days responding to the actions of those who cluster at the other end of the continuum.

As a short aside I might present the thought that of the nearly 64% who responded “moderate positive impact” there are many who ticked that middle response box as a nod to their self-preservational need to view their work as meaningful. Were they to dig deeper I offer that it is possible many would have come to the “dark side” and joined the those who were perhaps more realistic. As an aside, I wonder how their sentiment would sound to those that provide money to support their efforts to make “moderate positive impact.”

Here are a few responses to the open ended follow up question asking for respondents to elaborate on their views about the future of humanitarian aid work.

“This is specific to humanitarian work (emergency response, chronic humanitarian contexts). I do NOT believe that development work has a longer term positive impact, and I generally do NOT agree with development programmes.”

This first one represents many respondents who made a distinction between emergency response and development work. Indeed, as one respondent put it, “There is really no comparing relief and development…” While many felt that the former was necessary and doing positive action, the later not so much. This next one made me smile and was a good summary of this sentiment.

“Aid work is a bandaid. Bandaids are good! Transformative structural change is better.”

This next respondent hits my above points directly, we can’t let people die that can be saved (Dunant’s ghost appears…).

“As much as I believe that in the long terms humanitarian aid might have a detrimental impact (dependence on aid), I do believe that too many lives would be lost without aid in specific situations. We do need to keep working on linking humanitarian aid to real development.”

Elsewhere I discuss the semantic landmine that is differentiating between ‘aid’ and ‘development’, but I am haunted by Leslie White and Emile Durkheim. A bandaid is, indeed a bandaid and the beneficiary of that bandaid likely feels grateful having avoided bleeding to death, though I am not convinced that is always the case.

A question arises in my mind. In the case of famine relief can there be any other response than to provide food? Of course not, or so says my Westerncentric and hence anthropocentric mind. But is that the most culturally appropriate answer? In part the answer to that question depends upon your point of reference, of course, but that is exactly my point.

Castles in the sand 2.0 What are we accomplishing after all?

So, more aid worker voices to move our journey down this path a bit further.

“I don’t think the goal of the development industry should be to eradicate poverty, disease, or save lives – it should be to reduce the barriers that keep people from making informed choices about how to live their lives, be they economic, political, social/cultural, or whatever. Our industry suffers from a persistent messiah complex that, despite its earnest efforts, it can’t seem to shake. It is dehumanizing, destructive, and patronizing. Idealism drives burn out, of the “compassion fatigue” variety. Pragmatism makes it easier to let things go when they don’t work.

–30something female expat aid worker respondent w/ 10+ years experience

“There’s a reason all this professional jargon exists. It obfuscates the fact that at the end of the day most aid work doesn’t do much of anything.”

–mid 30’s male expat aid worker with 5+ years experience

“Something an old man told me in West Africa struck me. We were at a big conference on sanitation, and the guy stood up and said ’20 years ago I was at a similar conference where we discussed exactly the same issues, with exact same solutions. Now 20 years later we are still discussing the same things.'”

–mid 30’s female HQ worker

Having recently finished Nina Munk’s book The Idealist: Jeffery Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty (2013) I have a few thoughts on which I’d like to expand.

I’ll start by saying that Jefferey Sachs got it right, finally. “It is what it is,” he says in last pages of the book in response to Munk’s hard questions about difficulties encountered related to the Millennium Villages Project. The realization that he finally comes to -or reawakens to- is that everything is connected to everything else environmentally, politically and perhaps most importantly, economically both locally and globally. He says exactly that to Munk at the end off the book, “For a long time, I wanted to simplify the problems by putting aside the rich world’s issues and so forth and focusing on extreme poverty. But it’s all interconnected.” I am reminded of the statement from the anthropologist Miles Richardson who said, “…the problem of the poor is not the problem, the problem is the rich.” Much truth lies in that statement, and we now have an global Occupy movement that that is shining a bright light onto this reality.

The Sachs team’s 147 page Millennium Villages Handbook used in the select villages in Africa reported on by Munk and elsewhere was, in a very real sense, the guide to put into place the prescription he expounds in his The End of Poverty (2005), his vision -some say promise- to eradicate extreme poverty by the year 2025.

The Millennium Villages Project did the world a great, sobering favor in that it gave perhaps our (i.e.,more specifically, the Western, ‘scientific’) world’s best shot at trying to solve the problem of the poor and came up, predictably, short. Not because we didn’t try hard enough, but because the assumption is failed.

Certainly if we were listening to history we should have learned this lesson many times over. In his Doing Bad by Doing Good: Why Humanitarian Action Fails Christopher Coyne outlines in good detail the failed Kajaki dam project in the Helmand Valley Province in Afghanastan, calling it a “planners problem.” His alternative, a rehash of William Easterly’s arguing points in The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good (2006), is the so-called ‘constrained approach’, not much more than a repackaging of Easterly’s ‘seekers’ idea. Both argue this general ‘bottom-up’ approach will have a better chance of success making lasting change.

Coyne argues perhaps the obvious, i.e., that knowledge of the local culture is imperative for development work. He posits, correctly I believe, that “…[we need to appreciate] endogenous rules because existing rules place a constraint on efforts to design and implement what are perceived to be potentially superior formal rules” and further that “…attempting to impose formal rules that are at odds with underlying informal rules is akin too banging a square peg into a round hole–it can be done, but only with significant force and collateral damage.” Agreed. But we’re still in the weeds here talking about how to engineer sand castles.

Both Easterly and Coyne find support from Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa (2009) by Dambisa Moyo and of course Easterly continues to beat the same drum in his recent offering The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor (2014).

Easterly, for his part, argues very articulately for the position that by encouraging the rich and simultaneous exploration by many creative people -poor people- for useful and effective solutions to human problems we will all be the better for it. For my money, the Easterly/Coyne/Moyo (et al) arguments sound way too close to the neoliberal rhetoric washing around for the last several decades arguing that the poor just need to be given their rights and respect and they will solve the problem themselves or, rather, the forces of the market will make this happen and the efforts of the rich and newly rich(er) will ‘trickle down’ like so much sweet rain.

The Invisible Hand, in my view, tends to slap the poor while patting the back of the rich. Just sayin’.

Thus, the thesis statement for this post lies here: our globalized social world comprises one massive complex system – that, if I understand Kurt Godel, Emile Durkheim and Leslie White at all, cannot be meaningfully and permanently changed as a system by purposeful human behavior. Humanity is perhaps the most defining

nonlinear system of them all. In short, very subtle, trivial appearing

inputs can cause large unpredictable effects in both the short and most definitely in the longer term. Icing to the cake, we are also part of the complex ecosystem of the planet, also most definitely a nonlinear system. This is increasing so as the world gets more interconnected and complex and the the rate of social change, especially driven by technology, goes dizzyingly faster and faster. As one aid worker put it, “Compared to the money being invested, we’re doing a pretty poor job of getting anywhere. A lot of misguided approaches or self-interested approaches or inappropriate interventions or I could go on and on. Why do we know that poverty is not simple or linear

, yet still implement interventions as if it is? We need to get better. We need to be smarter, think more critically (emphasis added).”

We are not in charge of how the future will unfold, nor can we ever be. As aid and development work veteran Michael Hobbes put it “Maybe the problem isn’t that international development doesn’t work. It’s that it can’t.” He chimes on on the above mentioned Millennium Development Goals here (spoiler: he thinks they’re bullshit).

the future will unfold, nor can we ever be. As aid and development work veteran Michael Hobbes put it “Maybe the problem isn’t that international development doesn’t work. It’s that it can’t.” He chimes on on the above mentioned Millennium Development Goals here (spoiler: he thinks they’re bullshit).

Is there something/someone else at the driver’s seat? No, I will not go all InshAllah on you here: the future is not in Allah’s hands nor any other God or gods hands, however much we would like to believe that. If there were a loving God she would not allow the absolute horror that visits upon billions every day, especially the bottom 2 billion that are the focus of much aid and development work. That’s my opinion.

It is what it is. Our global community is an unfolding of what may be best described as a set of incomprehensibly numerous and complex algorithms perhaps the two most important of which are biological evolution and capitalism. The future will become what it becomes not because of what we -or those like Sachs, Gates, Easterly, Soros and others- want it to become but rather in spite of what we what we would like it to become.

To be clear, these fine folks, Easterly, Sachs and the rest are all basing their actions and arguments on one very flawed and hubristic anthropocentric assumption, namely that we are in control of how the global culture unfolds.

There are those who will point to the many human interventions over the centuries that appear to affirm the human capacity to control our civilization. My counter to these examples is that, yes, you can -and as I noted almost ad naseum, we must- build castles in the sand, and some of these castles will be magnificent indeed. But nonetheless these are more testaments to human will than true ‘directing the unfolding of human history’ moments.

In the final pages of Munk’s book she talks about the challenging social and economic changes occurring all over Africa that raise a very important question about the efficacy of the MDV’s project, namely would much of the change that happened in the target  villages occur even despite the massive intervention? The answer, quite likely, is yes. That is, change in spite, not because.

villages occur even despite the massive intervention? The answer, quite likely, is yes. That is, change in spite, not because.

I find good support for my position in Steven Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined in which he details the very counterintuitive argument that humanity is getting less violent over the centuries.

I disagree with what one respondent said when reflecting on the future of humanitarian aid. She said, “Human beings, we are not good.” Humanity is getting more humane in some ways as social institutions slowly evolve to tamp down our more violent tendencies and see ourselves more and more as one humanity. Sociologist G.H. Mead encouraged us to look forward to a time when we would have all humanity as our reference group, our ‘generalized other’ not just those in our immediate clan.

Can we impact this or that specific life with our actions? Of course. In fact that is what aid and development workers do every day of every year all over the world. Is that impact scalable, the kind that can ‘end poverty’? That indeed is the question I am attempting to address. I would say ‘yes’ in the short term we can create that appearance, but on a global scale not so much.

The problem of the poor will always be with us, I am afraid.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Ending thoughts on “eradicating extreme poverty by 2015”

Art, as sociologist Georg Simmel pointed out long ago, allows us to make observations about the world in creative, entertaining, and non-linear ways that are sometimes closer to the truth than we dare come with ‘scientific’ thought. Movies, for example, can sometimes allow us to face realities otherwise too stark to otherwise voice. The scenes below nod to Durkheim, I think.

“There are no nations. There are no peoples. There are no Russians. There are no Arabs. There are no third worlds. There is no West. There is only one holistic system of systems, one vast and immane, interwoven, interacting, multivariate, multinational dominion of dollars. … It is the international system of currency which determines the totality of life on this planet. That is the natural order of things today.”

“There are no nations. There are no peoples. There are no Russians. There are no Arabs. There are no third worlds. There is no West. There is only one holistic system of systems, one vast and immane, interwoven, interacting, multivariate, multinational dominion of dollars. … It is the international system of currency which determines the totality of life on this planet. That is the natural order of things today.”

Jensen lectures poor Howard Beale further…

“There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM, and ITT, and AT&T, and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state, Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable bylaws of business.”

I am not entirely sure Arthur Jensen/Peter Finch got it wrong back in 1976 in Network when describing the nature of global capitalism. No one is in control of how this algorithm plays out, though some learn how to benefit disproportionally.

Jensen uses phrases like “natural order of things” and “immutable bylaws” to describe the world, in effect citing Durkheim. Can we ever reach our goal to “eradicate extreme poverty” at any point in the future? Perhaps not. Though to be clear, I do think that poverty may someday, possibly, be eliminated in our world but that it will not be mindfully engineered by the likes of Gates and Sachs, et al, but rather happen as an organic product of the many dynamic systems at play, that is not because of human agency rather despite it.

With that, I now turn next to examining in more detail the aid worker voices on the topic of their idealism and future of humanitarian aid.

[To be continued]

As always, reach out to me with your comments, feedback or snark by clicking here.

Tom Arcaro is a professor of sociology at Elon University. He has been researching and studying the humanitarian aid and development ecosystem for nearly two decades and in 2016 published 'Aid Worker Voices'. He recently published his second and third books related to the humanitarians sector with 'Confronting Toxic Othering' published in 2021 and 'Dispatches from the Margins of the Humanitarian Sector' in 2022. A revised second edition of 'Confronting Toxic Othering' is now available from Kendall Hunt Publishers

More Posts - Website

Follow Me:

many to be quite self evident, and arguably these policies impact, well, every aspect of social life on this planet. The respondents above articulate that quite well. They also make the point that there will always be a need for humanitarian aid because the dominant global powers insure inequalities and marginalization.

many to be quite self evident, and arguably these policies impact, well, every aspect of social life on this planet. The respondents above articulate that quite well. They also make the point that there will always be a need for humanitarian aid because the dominant global powers insure inequalities and marginalization.

Follow

Follow

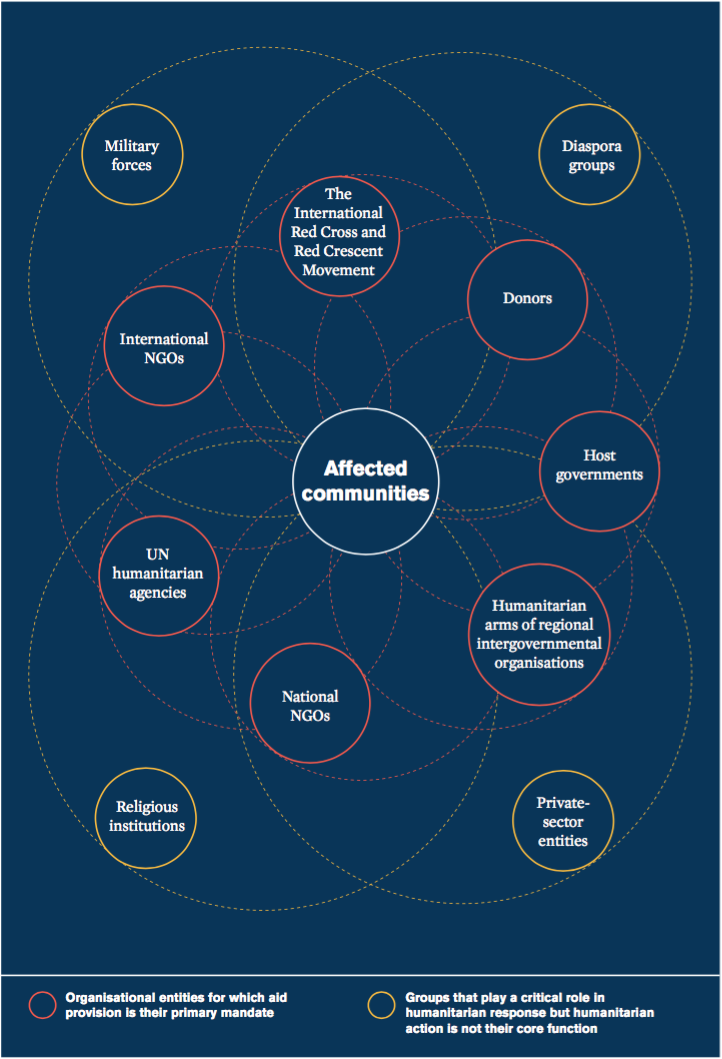

agree that it is and should be seen as a profession- there are umbrella entities like ALNAP that are taking proactive measures to both understand and make positive changes to the humanitarian aid system. Indeed, the establishment of the

agree that it is and should be seen as a profession- there are umbrella entities like ALNAP that are taking proactive measures to both understand and make positive changes to the humanitarian aid system. Indeed, the establishment of the