Written in response to Q7: “Why does it have to be white as point of reference?”

Indeed.

You are as you are seen: race/ethnicity/cultural identity

Branding is for all of us

Branding is important. Indeed, organizations spend a great deal of time, effort and money to “get their name out there” and to have their logo be recognized as something desirable or positive. The vast majority of all social entities -be they for-profits, political parties, social clubs or, indeed, non-for-profit humanitarian aid organizations- worry about public relations and will make efforts to “spin” what is known about them using social media, press releases, advertising and a myriad of other techniques.

You and I do this as well constantly albeit not always consciously. Sociologist Irving Goffman‘s work on impression management remains part of the canon, and his 1959 book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life could be useful reading for aid workers at any stage of their career.

One of the key insights that I gained from reading Abu-Sada’s (ed.) In the Eyes of Others is that though an NGO -in this case MSF- may go to great lengths to brand themselves, people on the receiving end of aid tend to see the “crisis caravan” as a monolithic Western entity. All of us, though we may try to “brand” ourselves as our own unique person (“I am truly wonderful! — in a complex and nuanced kind of way, of course”) find that sometimes we are not seen as who we think we are but more so a generic category like “female”, “white”, “young person”, “Western”. And, yes, that does describe our modal survey recipient.

Indeed, in many situations despite our efforts to manage our identity, we find that we are as we are seen: “female”, “white”, “young person”, “Western”.

The race question

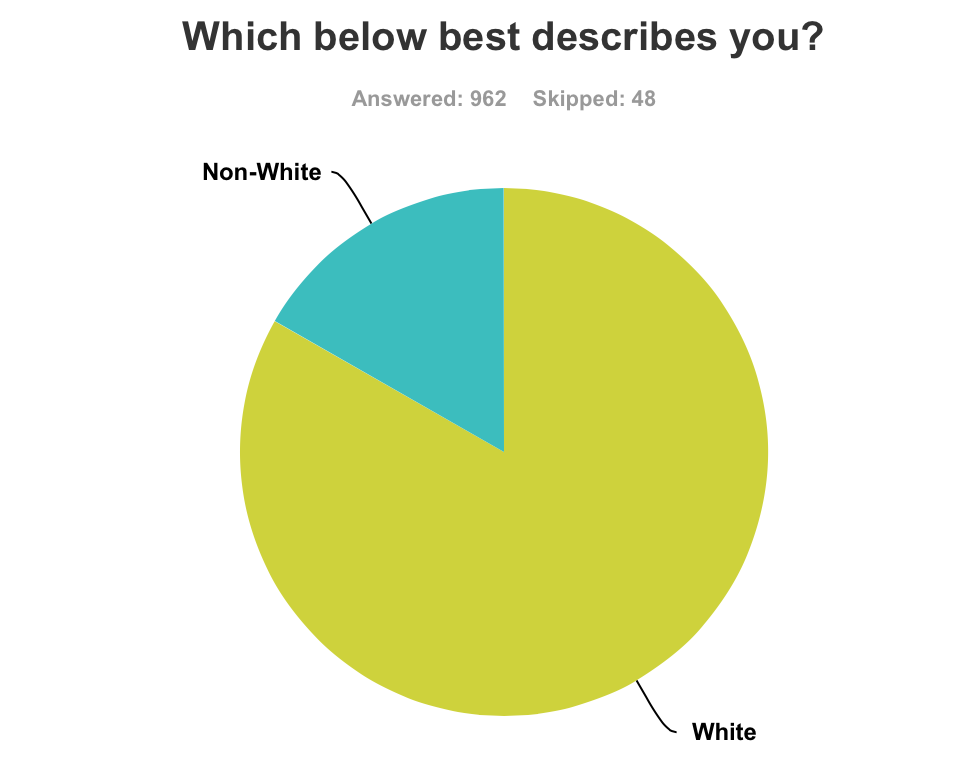

When writing the “race” question for our survey we wanted to get at the tremendous depth and complexity of this part of one’s self concept and in the end decided a more or less direct approach. Q6 asked “Which below best describes you?” giving only “white” and “non-white” as the only possible choices. That was the bait. The followup Q7 then asked “Please use the space below to (1) react to the inappropriateness of the choices in the question above and (2) describe how you identify yourself based on common cultural-linguistic, ethnic, racial, tribal, national or other categories.”

Most everyone who stated the survey, 991 people, answered the “race” question (Q6) and 542 (56%) giving at least some narrative comment in Q7. The bait worked, and in numerous instances the respondents were insightful, articulate, poignant and often hilariously funny. As is the case when nuance is used, some did not appreciate our attempt.

Of note but somewhat predictable is that a higher percentage of “non-white” respondents chose to write a followup Q7 response, nearly two thirds,66%, doing so as compared to just over half, 53% of those identifying as “white.” Not only did more “non-whites” respond, their average word count was about 19% higher as well. They had a bit more to say.

Some thoughtful examples to start

These first two examples hit well on both parts of Q7, with the first one well worth a close read, methinks:

“(1) I think the choices in the question reflect the notion that aid workers can be classified in just two categories: white (either North American or European, expats with higher salaries and more leadership positions than locals) and non-white (the locals from whichever developing country the organization is established, working alongside the white leaders, doing most of the grunt work on a lower salary. Much like the Lone Ranger’s Tonto, if that’s not too rude of an analogy). Is this notion inappropriate/politically incorrect? Perhaps. Is it false? I don’t think  so. They’re simply caused by the resulting power dynamics in a context where whites are generally better prepared to handle the global networking required for the growth and expansion of an organization, and the non-whites/locals, who are better prepared to conduct all the field work without wreaking culture-shock havoc on the beneficiaries. (2) As for myself… I always say I have a nationality crisis. I was born to a Nicaraguan mother and an Iranian father. I have dual Nicaraguan/Canadian citizenship, and spent most of my childhood and adolescence between countries in a culture-neutral household (because of the cultural differences between my parents, my home life never mirrored the culture of the outside world, wherever we may have been living at the time), so I grew up as more of a cultural observer rather than replicating any of it. Physically, I’m ambiguous, people can never place where I’m from. I think and express myself more naturally in English, but I write all my “romantic, thought-out masterpieces” (I’m one of those frustrated writer people) in Spanish, I also speak French and I read and write Farsi (although the vocabulary has long been locked up in my brain, having fallen out of use when I was three years old). The only place where I don’t feel completely external to the culture around me is in an office full of converging personalities from all over the world where the dominating atmosphere is “tolerance”, not some unspoken attitude pattern that everyone seems to know except for me. And this is not because it sounds so “Oh, I’m a citizen of the world, y’know?”, but because everyone is just as awkward and culturally-misplaced as I am. But, for practical purposes, I am Nicaraguan in Nicaragua, and Canadian everywhere else (less visa issues).”

so. They’re simply caused by the resulting power dynamics in a context where whites are generally better prepared to handle the global networking required for the growth and expansion of an organization, and the non-whites/locals, who are better prepared to conduct all the field work without wreaking culture-shock havoc on the beneficiaries. (2) As for myself… I always say I have a nationality crisis. I was born to a Nicaraguan mother and an Iranian father. I have dual Nicaraguan/Canadian citizenship, and spent most of my childhood and adolescence between countries in a culture-neutral household (because of the cultural differences between my parents, my home life never mirrored the culture of the outside world, wherever we may have been living at the time), so I grew up as more of a cultural observer rather than replicating any of it. Physically, I’m ambiguous, people can never place where I’m from. I think and express myself more naturally in English, but I write all my “romantic, thought-out masterpieces” (I’m one of those frustrated writer people) in Spanish, I also speak French and I read and write Farsi (although the vocabulary has long been locked up in my brain, having fallen out of use when I was three years old). The only place where I don’t feel completely external to the culture around me is in an office full of converging personalities from all over the world where the dominating atmosphere is “tolerance”, not some unspoken attitude pattern that everyone seems to know except for me. And this is not because it sounds so “Oh, I’m a citizen of the world, y’know?”, but because everyone is just as awkward and culturally-misplaced as I am. But, for practical purposes, I am Nicaraguan in Nicaragua, and Canadian everywhere else (less visa issues).”

“1.a. i find interesting the number of choices (and the choices themselves) for Q#4 and Q#6 – i would be interested to hear why they were developed in this way. 1.b. I am not sure i find the relevance of the options under Q6, unless the goal is to determine a trend in the history of international development/humanitarian aid. if this is the case, it would be useful to see if the % of white humanitarian workers from traditional main donor countries has shifted in favor of non-traditional or non-donor countries. in addition, I think most people would not identify themselves as white or non-white (even if they were white) – not to mention that this implies that white would be the point of reference. 2. I am caucasian, but most beneficiaries I worked with were surprised/ disappointed I was not American, Candian or British. By name and accent I have been identified as: Italian, Indian, Pakistani, Mexican, Spanish, Russian, Arab, Turkish, Ukrainian, Polish. i find it less important to identify myself by standard ethnic categories when we live in such a mixed world, especially in a job where it’s more important how you adapt to the culture/ethnic group you work in, rather than the one you come from.”

To the point

And then we have the pithy:

“Outraged at above question, passed on outrage to the office, before seeing this question. Identify as White, British.”

Some appeared to dislike the question and judged: “(1) This is racism and sexualism. (2) World inhabitant.” and others just the opposite: “I love this question but (predictably) fit into the categories above.”

Funny/Sarcastic

These examples made me smile, though all for different reasons. The last one hits what was a common point made by many, i.e., whether we like it or not, color matters.

- 1. inappropriate response to inappropriate question. 2. I identify myself and others based on a complex correlation of the amount of stamps, number of passports held and whether or not a person uses a mac.

- I had to check with my colleagues about what my answer should be. I have a white skin, but the definition of white in survey usually is caucasian white, which I am not. I am Lebanese first then an Arab.

- 1) I get it, most expats are white, f*ck us for caring 2) Yooper

- I’m not sure “white” appropriately captures the whiteness of a white Canadian woman working in development. You should have used “pasty”.

- HA! I was wondering why that was so horribly stated. Points for humor. I am American, white, English-speaking, blue-collar-rust-belt SES, yet ultimately over-privileged in the grand scheme.

- White but not Anglo-Saxon. No post-colonial guilt trip.

- 1) Sadly reflects the world view in many cases. 2) Why can’t we all just have two boxes: human and non-human?

- I’m really white. White, middle class American. Blonde, even.

- Not surprised — when we’re “in the field” we are often self-identified as being either white or non-white. It’s icky, it feels wrong, and yet, there it is. Skin color tells half your story for you before you’ve even opened your mouth.

Perhaps missed the point

- 1) only albinos would consider themselves ‘white’ in my opinion. 2) I am me. I accept me. Just the same as I accept all those not me. Colour is irrelevant.

- The world thank god is not so black and white.

- Appropriate or not, skin color simply does not provide any meaningful data. Despite its limitations, a regional identity would be more significant here. In my case, my identification as a European suffices for this survey.

- This description works for me as I am white bread, but if I had to identify as non-white as my only option I would not be very happy! It is like colonizer or colonized. Possibly we could look at a description of pigmentally challenged vs not pigmantly challenged? But seriously I have never understood the value in these types of questions…

Thought provoking

There were many responses that underlined the main point I am making in this post. Here is one that hits that perfectly: “Those choices were very inappropriate. Yet, I am still white. It is not so much that to me, this is my most distinguishable feature, but living in Africa, it somehow seems to be so to others.” Where you are in the world -your social context- has a big influence on how you are seen. The following examples restate that point in various ways and illustrate the sad fact, again, that color matters.

- I’ve noticed that in the African country where I work, everyone who is not ethically African (black) is “white.” So I’m not sure how this question plays out with say ethnic Indian Africans?

- I think that there’s absolutely a place for this question, provided that we’re given the opportunity to react. Perhaps the question is halfway there, and you should be asking how we identify versus how we’re perceived. This probably comes from my time prior to entering the aid sector, when I worked with Indigenous Australian communities, and was familiar with extensive debates regarding whether you were ‘black enough’- I worked with a number of Indigenous Australians who appeared outwardly ‘white’ but identified strongly with their Indigenous heritage. So while these people were absolutely Indigenous, they were often treated as ‘white outsiders’ who had no place making policy decisions or managing community programs. It’s a complicated issue, but it’s often perceived as (pardon the horrendous pun) black and white. So maybe the question comes from this perspective and is appropriate in that sense. I would be really interested in hearing the discussion that took place around this question some day! As for me, I’m a white Australian of German and Namibian heritage. I was raised speaking English and some German. Aside from the cultural-linguistic/ethnic/etc business, I also identify as a queer woman.

- It sets up a dichotomy and forces one to choose between two categories that don’t best describe an individual. There are many more adjectives that I would use to describe me. It sets up a world view which I have to deal with on a daily basis but would like to see us move beyond.

- It would be best if it didn’t matter, but it usually does, and it’s most often the distinction above that does matter. you can’t list every race, every selection will be inappropriate to someone… I’m European.

- It’s pretty blunt. It’s certainly imbalanced and biased to see a global minority written down as a majority, and other majority generalised as a “other” group. Many expat aid workers are white, and are defined as such by each other and local populations (whether ethnically white or not), so the options reflect conversations you hear but it’s stark to see written down.

- In terms of how whiteness tends to inform differential treatment of and reactions to aid workers by both their organisations and the populations they serve, this split may be depressingly appropriate.

“White” and “non-white” differences

There was a slightly higher percentage (66%) of “non-white” respondents that chose to respond to Q7 than “white” (53%), indicating that this was a slightly more important question for those that self-identified as “non-white.” What I have found in these “non-white” responses are the same patterns as in the “white” responses, mostly that identity is both incredibly nuanced and at the same time quite binary. This one sums it up well:

“I am Filipino-American. Colleagues in the Philippines treat me as a local/national with a foreign passport. I have similar experience in other countries within South East Asia. In West and East Africa, I am often perceived as Chinese. In the Middle East, my ethnicity is often associated with hired domestic help. I am extremely proud of my ethnic background and cultural heritage but there have been times in the field when I wanted to look like the typical expat aid worker – 6 feet tall, blond and very white. The color of one’s skin shouldn’t matter especially in this line of work, but who are we kidding?”

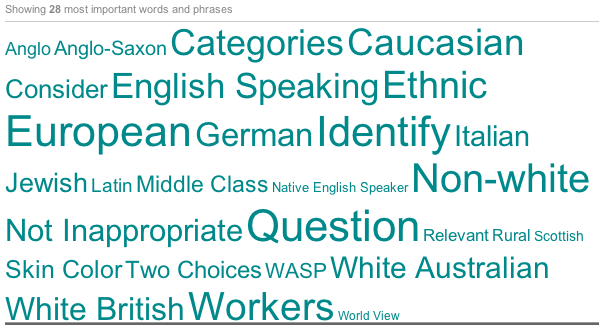

Here are the “word clouds” from both. Quite obvious which is which.

Aid worker voices regarding identity

Many respondents used this open-ended question to riff and reflect on their identity, and I was a bit surprised at the range of identifiers that were used beyond the obvious country/region of birth, etc.. “Atheist” was not uncommon as was “queer“. Many used the opportunity to express a sense of global citizenship (“Global citizen of Georgian origin.”) and/or anti-or a-nationalism. One respondent simply wrote “nomad.” Those who were comfortable as seeing themselves as fitting neatly into a category (e.g., German or ‘Murican) were one large group, but a roughly equal number went into some detail about how what they saw themselves as was quite complicated (as seen in many examples above).

What, if anything, can be concluded from the responses to Q6 and Q7? Aid workers in general have a sense of humor but more importantly most have an in depth and critical sense of identity -both who they are and who they are seen as. Most recognize the reality of white bias both within and outside of the aid industry and many struggle with the “race” question on many levels. Those with more stamps in their passport will recognize the fact that “white” or “non-white” matters a great deal in some parts of the world (much of Africa) and less so in others. I will hazard that seasoned aid workers manage their identity as much as they are able in order to maximize their effectiveness (and/or personal safety) in various situations and locations, accenting or downplaying gender, race, SES, or other status markers so as to get by successfully in various contexts. But despite our very best efforts and intentions we are as we are seen by others much of the time.

As always, contact me with questions or comments.

Postscript

A question: What does it matter how you see yourself or even how others see you -that is, what is happening in the minds of people- as long as the job gets done? Perhaps the more important question is to what extent does your sense of self and how others see you in the field impact what you do, what gets done?

Follow

Follow