“We are band-aids born of affluent guilt and survive almost entirely on the donated profits of unjust privilege and power.”

“WTO, WB and IMF policies and corrupt/ignorant/criminal national elites matters million times more any humanitarian program implemented by NGOs.”

Some thoughts as I continue reading, sorting and making sense of aid worker voices on the future of humanitarian aid

[Note: I am working on a long post (chapter) on this topic, but I wanted to get this out separately.]

So, I have been reading through -in many cases re-reading and re-reading…- the 311 narrative responses to the “future of humanitarian aid work” (Q60) on our aid worker survey and I am struck over and over again with the depth of thought put into some of the responses. Though there were many who responded from a short term or narrow view, many were clearly of the ‘35,000 foot’ and long term perspective.

One theme that I see very clearly is a healthy neo-Marxist/anti neoliberal assessment of the ‘big picture” relative to not only the aid industry but our entire international community. Many echoed the oft quoted sentiments of former UNHCR chief Sadako Ogata. “There are no humanitarian solutions to humanitarian problems,” said Ogata, explaining that in the many emergencies she oversaw at UNHCR, humanitarian relief in itself was not enough because the problems were caused by political factors.

Here are a few examples.

“The big picture is that developed world is fucking [the] developing world over so that anyone in Europe and America can buy a T shirt and an iPhone. Without more political and economic engagement of developed countries things will remain fucked up in the developing countries (debt, corruption, zero accountability). I hope with growing awareness citizens in developed countries will pressure their authorities more, but I’m a hopeless optimist.”

And then this one, with just a bit less salt:

“I think humanitarian aid work operates within a system that is built on inequality – we won’t see large scale change happen in the lives of people, in terms of long term development, until we start to challenge the structures and systems that result in this inequity in the first place. And the heart of those institutions is within North America and Europe – until we recognize how dependent we are on the oppression and marginalization of others for our own betterment and benefit (i.e. access to cheap disposable goods, foreign foods and fresh imports, temporary foreign workers to fill low-income job vacancies, etc…), humanitarian aid work is just another cog in this bullshit machinery.”

And then this:

“We are doing nothing to change the power structures that generate the social problems we try to fix. We are band-aids born of affluent guilt and survive almost entirely on the donated profits of unjust privilege and power. Unfortunately, such views are seen as too radical to be productive and those conversations are rarely engaged with.”

What I see in all three above meshes well with what I wrote in my previous post discussing the long term impact of humanitarian actions, namely that aid does not exist in a vacuum but rather is part of an extremely complex array of non-linear algorithms over which we have little -or no- long term control.

That neoliberal and myopically pro-capitalistic economic policies remain dominant in our world seems to  many to be quite self evident, and arguably these policies impact, well, every aspect of social life on this planet. The respondents above articulate that quite well. They also make the point that there will always be a need for humanitarian aid because the dominant global powers insure inequalities and marginalization.

many to be quite self evident, and arguably these policies impact, well, every aspect of social life on this planet. The respondents above articulate that quite well. They also make the point that there will always be a need for humanitarian aid because the dominant global powers insure inequalities and marginalization.

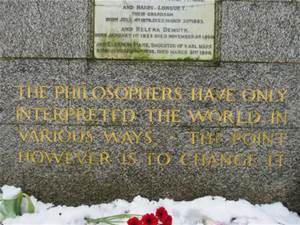

So, where to go from here? One answer might come from a social thinker from the past who’s ideas may be relevant today, “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” This line, in fact, is his epitaph engraved in stone at Highgate cemetery.

More realistically (?) we can all ceaselessly work on shorter term goals of major importance. One positive path is captured by this respondent, arguing for continued professionalization of the sector.

“The sector is professionalizing but still has a way to go. It is a complex sector to work in and would benefit from a more recognizable professional accreditation system to ensure recruitment of people into the sector is merit and competency based and to dispel the notion that this is an unskilled or vulnerable sector populated by idealistic adventure-seekers.”

Echoing a sentiment I have referenced previously, namely that ‘the problem of the poor is not the problem, the problem is the rich’, this next respondent encourages a paradigmatic shift by the affluent nations that can only be brought on by educational work. Though I admire the optimism, I am not holding my breath on this one.

“I think the evidence base continues to show significant impact and improvements in many places. The big challenge is ensuring the complexity of systemic injustice changes the way the wealthy nations live so that aid doesn’t become a bandaid over deeper problems. For example, if people don’t live justly (ethical shopping, investment, simple, enviro friendly, peace building) in the west then we are not really addressing the underlying systemic issues. We need to move from a simple ‘give money to this poor child’ mentality to a social justice/change the way we all live mentality. Thus increasing importance of educational work rather than just slick marketing and challenges the sector to tell the complex story of change…”

This one, more cynical but perhaps at the same time more accurate, sums up a big part of the battle.

“WTO, WB and IMF policies and corrupt/ignorant/criminal national elites matters million times more any humanitarian program implemented by NGOs.”

To put it in the vernacular, draining the swamp is the only long term solution, and in this case ‘the swamp’ is only getting more entrenched. This respondent makes the same point using what I think is a good analogy.

“Humanitarian aid work is more and more like firefighters. We are not the ones in charge of pursuing those causing the fire to stop them, we just jump from one emergency to the other, and that will not change things for good.”

That there is meaningful work to be done we can all agree. What that work is and how to best do it is the question that must remain at the forefront all our strategic planning for the future.

And yes, more to come.

Contact me if you have comments, snarky or otherwise. @tarcaro on Twitter.

Follow

Follow