Remittances as part of the humanitarian ecosystem

Critically important for every 1 in 7 people on Earth

A very high percentage of refugees and immigrants now living in the minority world (aka ‘Global North’) regularly send money back ‘home’ to family and friends they left behind. These funds, typically in small amounts and sent every month, are mostly used for health care, living expenses, school fees, and other necessities. The term for this transfer of funds is ‘remittances’.

I make a point of defining this term because in conversations with both my students and with even generally well informed friends and colleagues I have found that they know little to nothing about the fact that remittances exist and, more importantly, how critical they are to the alleviation of poverty in the developing world.

Here are a few relevant data points about remittances.

Here are a few relevant data points about remittances.

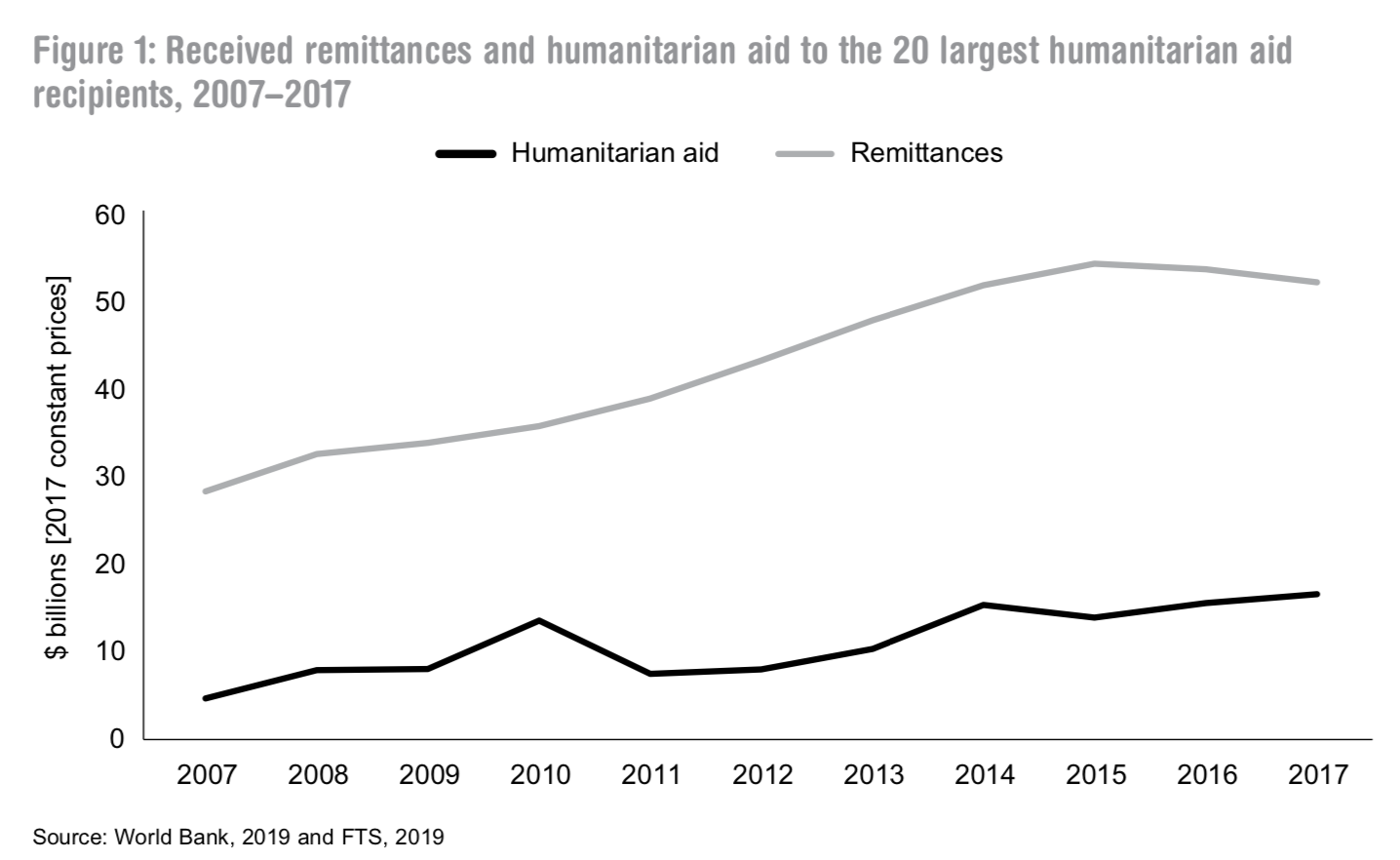

According to the World Bank in 2019 over 200 million migrants transferred remittances totaling over $612 billion, with more than $440 billion being sent to developing nations. To put this in context, in 2019 the total amount of development aid being sent by ‘rich’ nations to the developing world was just over $150 billion. Remittances account for more than three time as much as traditional development aid funds sent by nations like the US and the UK.

(See illustration above.)

According to the UN, over 1 billion people on the planet -one in every seven people in the global population- are either sending (200 million) or receiving (800 million) remittances, and over half of the funs that are sent go directly to rural areas of the world. Recognized as contributing to several of the goals set in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, June 16 has been set by the UN as International Day of Family Remittances.

For the most part, the aid we and other nations send to the developing world is a humanitarian act, meant to confront both the consequences and the causes of poverty, but research makes clear that remittances have a much higher positive impact than direct aid on poverty in the developing world.

Making remittances is the ultimate fulfilling of the humanitarian imperative

This flow of remittances around the world represents the best of humanity, families broken apart continuing to help those left behind. The act of sending $50 or $100 a month from an already anemic budget to assist mothers, brothers, cousins, and family friends is the marginalized helping the marginalized, a clear expression of the humanitarian imperative. In the Code of Conduct for the ICRC (International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement), the humanitarian imperative is defined as a fundamental humanitarian principle, “the right to receive humanitarian assistance, and to offer it”. Though not organized or coordinated on any significant level, those giving and receiving remittances can be viewed as part of the humanitarian/development ecosystem.

Here is what Jennifer Foy, Vice President for World Relief, a US based international humanitarian INGO, had to say about remittances,

“The vast majority of refugees send back remittances. I would estimate 80 to 90 percent that have family overseas that they’re close to especially those with family in camps or displaced in cities send money back home. It’s [sending remittances] a big part of their life and a big motivator for them to work. They come here and are are continuing to sustain friends and family back in their communities of origin.

“The vast majority of refugees send back remittances. I would estimate 80 to 90 percent that have family overseas that they’re close to especially those with family in camps or displaced in cities send money back home. It’s [sending remittances] a big part of their life and a big motivator for them to work. They come here and are are continuing to sustain friends and family back in their communities of origin.

I asked Jennifer what the refugees got from making these sacrifices. She said,

“It’s peace of mind; it’s knowing that their family is taken care of. In some cases helping their family survive long enough to join them here. Immigrants and refugees sending back remittances embody the humanitarian imperative.”

Indeed, relocated refugees are both ‘recipients and givers of humanitarian assistance.’

Coronavirus pandemic impact on on remittances

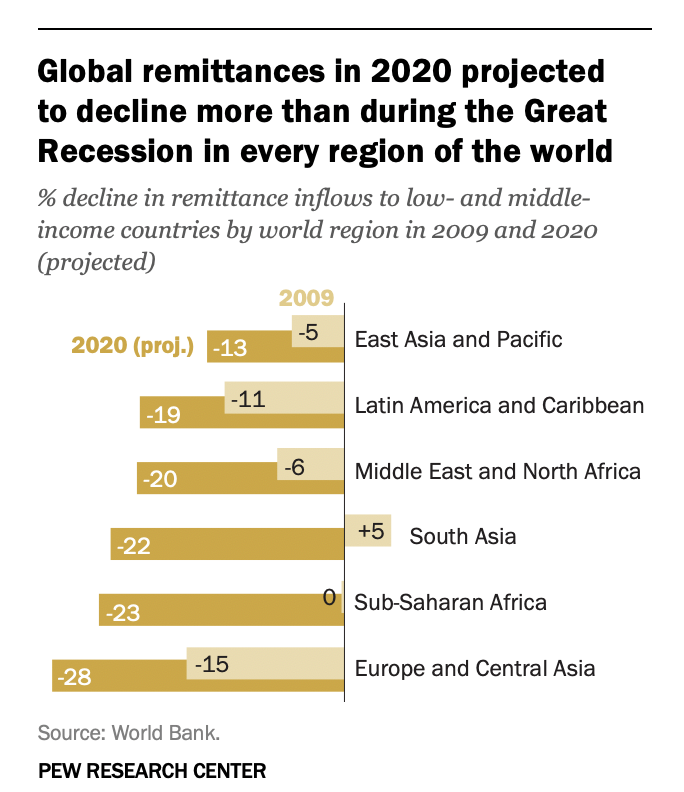

According to the Pew Research Center analysis of World Bank data, the coronavirus pandemic is beginning to cause massive long-term economic upheaval, constituting a major  humanitarian crisis. Nations, already suffering from both natural and human made disasters are made even more precarious by this sudden and catastrophic economic disaster.

humanitarian crisis. Nations, already suffering from both natural and human made disasters are made even more precarious by this sudden and catastrophic economic disaster.

Here’s how Jennifer from World Relief described the impact on the immigrant population here in the US,

“Immigrants tend to be the first ones laid off in many cases because they are in the entry level jobs. So when the factory shuts down, the restaurant shuts down, the people who tend to be affected at such a high rate will be the immigrant population.

But I have no doubt they can survive. They do amazing things and still send money overseas. But it’s going to be hard in that are going to have to make choices between ‘do we have 3 meals a day here or do we have one or 2 meals a day in our house but still send money so Gramma can eat back home’. They’re going to put pressure on themselves to continue to support and make the sacrifices to be able to continue that support.”

The coronavirus pandemic will have many negative and long-lasting impacts, and the significant decline in remittance flow will put many already on the margins at further risk. Given that donor flow is connected to overall global economic health, this recession slows this essential failsafe for many. The humanitarian ecosystem is responding aggressively and proactively to this pandemic, and the best new can hope is that the aphorism ‘necessity of the mother of invention’ will make the sector smarter.

Added note: See here for a quick look at the impact of coronavirus on remittances.

As always, please email any comments or feedback to arcaro@elon.edu. Go here for more views from Jennifer Foy.

Follow

Follow