Getting our survey out: exploratory research

Aid Worker Voices: Survey Results and Commentary

I’ll start with some very deep and reflexive background. In 2000 I published a book that was used by colleagues here at my university in a required course by the same name, Understanding the Global Experience. When I was asked to teach one section of the pilot for this course in 1994 I used that moment to begin taking a deep interest in global affairs. I recall reading Benjamin Barber’s The Atlantic article Jihad vs McWorld and being immediately absorbed by the vague (or is that vacuous?) concept of global citizenship. My interest in all things global only accelerated from there. As past President of the Association for Humanist Sociology my attention regarding social justice issues was already advanced.

In 2003 I founded a program at my university designed to offer a three year pathway for students who wanted to do something about global social issues as they deepened their knowledge. Our program is now well into its second decade of “creating and sustaining meaningful global partnerships.” As director of this program I have made it part of my job to learn about humanitarian aid and development and have read, taught and written about this area for many years now.

As part of my reading I encountered Missionary, Mercenary, Mystic Misfit by this mysterious J person. Through networking I found a mutual friend and he and I met on line, immediately connecting on the idea of finding out more about the lives and views of aid workers.

The survey

My collaborator (J) and I worked to construct the survey over many weeks, sending out versions to beta readers several times and making edits, adding and deleting questions, and finally ending up with a 60 item survey with 41 forced choice questions and 19 “elaborate on your thoughts” open-ended questions. The url for the survey was sent broadly via social media targeting at aid workers worldwide. At the end of the survey was a link to the AidWorkerVoices blog so that people could see our reporting and comment on the results as they came in. J gave a detailed clarification of who should take the survey on the blog that casts a pretty wide net. See here his answer to the question “Who should take this survey?” We stayed live for a little over a year and during that time we had 1010 responses, most coming in the first three months.

There were a total of 8,162 total responses to the 19 open ended questions, an average of 430 per question, including nearly 900 on the last two open-ended questions (Q58 and Q60), indicating that the interest levels of the respondents remained high and consistent throughout this long survey.

Our sample of aid workers

There is no master list of aid and development workers around the world nor for that matter any clear consensus as to (1) where aid ends and development begins (what is Dadaab, exactly?), (2) who could or should be included under the umbrella term “aid workers” (do volunteers count??) or even (3) how one would define the “aid industry” (does corporate social responsibility count, for example?)

To do a representative study of aid workers around the world we would need access to data bases of staff from everywhere in the aid industry, and effectively and efficiently get a culture and language specific version of the survey to a stratified random sample of these folks and hope that enough respond to make the results meaningful. If that were possible then we could make scientifically valid generalizations about the data.

Our survey was never intended to yield results that one could -with certainty- generalize to all aid workers. From the very beginning we were sober about the fact that our respondents were self-selected and, in the end, only fluent in English. What you read throughout this blog are aid worker voices from women and men who graciously gave their time to complete the survey. In my posts (soon to be book chapters) I summarize and commented on the quantitative data and the themes that appear in the hundreds of responses to each open-ended follow-up question. I make every attempt to present a balanced representation of the responses as a whole, highlighting particularly well articulated observations.

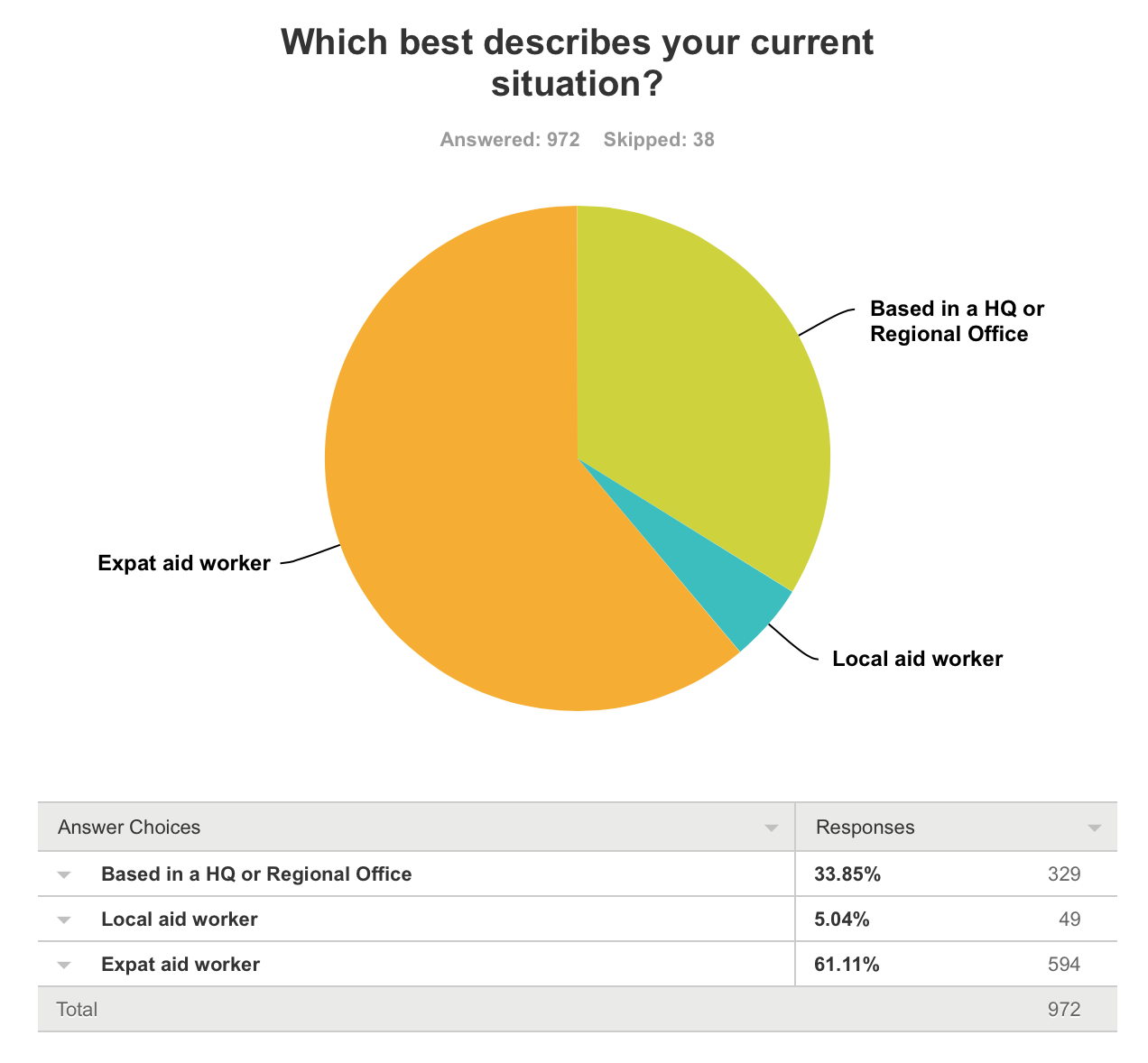

That the 1010 respondents tend to overrepresent expat aid and development workers from “rich” countries (the Global North and in particular the US, Canada and Western Europe) seems quote certain from both the quantitative and qualitative data. The title for the blog is Aid Worker Voices because “Mostly international aid and development worker voices from mostly ‘rich’ countries” was a bit too long.

What we have in this body of work is a positive step forward in exploring and giving voice to the views and lives of aid workers. Our results are scientific in the same sense as much anthropological work and, in the end, adds to our knowledge about the aid industry. The hope is that the book-length treatment of the results will be useful to students, journalists and academics wishing to learn more about the aid industry and will provide interesting and perhaps affirming reading for those already in the sector.

Our attempts at inclusiveness

Though we were able to generate over 1,000 responses to our survey it is clear that we have nothing close to a representative sample of all aid workers, however defined. Nor was that our goal. We simply hoped to move forward conversations about the lives of aid workers and to give voice to some of the concerns and perspectives of those willing to come forward, and I feel that that objective has been reached. In the vernacular of my academic area of sociology, our efforts represent an example of exploratory research intended to do exactly that, explore and share information about the lives and views of aid and development workers. More needs to be done, and a second version of our survey may happen at some point.

In the meantime, looking back at our efforts to get a wide range of voices I see some failed attempts.

Translations

A great deal of work was put into translating our survey into Spanish and Arabic. As soon as the translations were completed and vetted by native speakers we used various social media platforms to aggressively invite non-English speaking aid workers to respond to the survey. As we were putting the word out about the Spanish and Arabic versions we also spent time getting a version translated into French. Sadly, our energy and focus waned when our invitation on the Spanish and Arabic versions received literally zero reaction and the French version was never vetted or made public.

Why this lack of response? Two interrelated reasons are that (1) our social networking failed to get the word out effectively and (2) those that were reached felt unimpressed by our offer. But why? There are many reasons from various cultural perspectives, one of which is that the trust in the confidentiality of an internet survey may be low. Another is that the survey, if read at all, was seen as unworthy, off point, or otherwise not worth the investment in time.

or otherwise not worth the investment in time.

Here’s a comparison note, though. As part of another research project in 2008 and again in 2012 I put out an internet based survey targeting non-believers -atheists- that was of comparable length and depth to our aid worker project. The survey was called “Coming Out as an Atheist” so there was little doubt as to our target respondents. Using social media connections to get the word out in both 2008 and 2012 we were able to generate over 8,000 respondents for both versions – over 16,000 combined.

Detailed analysis of the data indicates minimal trolling; the answers were consistent, sincere and detailed. Over 92% of those who started the long surveys completed them. And here’s the kicker: though most of our respondents were from the US (about 70%) a good minority were from around the world. Though a relatively few were from the global south, about 4%, this population was reached. The massive success of both of these surveys (in terms of getting a robust response) even though the topic was potentially stigmatizing was what made me feel like we could get a good response from aid workers world wide.

Indeed, we are comparing apples and oranges in terms of numbers here. Globally there are likely far less than 500,000 aid workers, however defined, just now. The number of nonbelievers/atheists worldwide is in hundreds of millions, with as many as 30,000,000 in the United States alone. That said, coming out as an atheist is far more risky in many places than coming out as an aid worker, so the fact we got so many responses is partially a function of the fact that, as expressed by many in the open ended questions, taking the survey was cathartic.

We did find the same responses in our aid worker survey, though. Here are a couple examples:

“Very interesting survey and I appreciate the chance to share my views – it is surprising how little time (and few opportunities) one has to actually *think* about things in the busyness of the day-to-day. I wish your survey results could be shared in an open forum (not only virtual) where significant players can be present and honestly reflect for a moment.”

“These are great questions; very thought-provoking. It’s rare to have an opportunity to share ‘my truth’ so I appreciate this initiative!”

So, given that many people thanked us for the survey and appreciated the chance to share, the question remains why didn’t we get more responses overall and none from the translated versions?

Local aid workers

We were also concerned that we did not get many responses from local aid workers. Though our social media messaging about the survey was meant to reach all aid workers, the outcome was far more homogeneous and, well, white. Over half of the local aid workers that responded to our survey worked

for humanitarian aid organization and comprised a paltry 5% of our total sample. How this could have been more effectively addresses is open to question, but certainly one large gap in our goal of hearing and reporting the voices of aid workers is the very critical local aid worker segment. In some senses our blog [book] could be said to be “International aid worker voices”, sadly so.

Concluding thoughts about being inclusive

That we had failed attempts at inclusiveness is obvious. But what can we learn from these failures? Here are some final thoughts:

- There could have been different versions of the survey pointed at various audiences and written in collaboration with (and in the local languages of) the local aid workers themselves and/or other academics and researchers.

- The Arabic version needed an Arabic person to lead the social media awareness efforts about the survey and that this version should have been written by an aid worker who is a native Arabic speaker.

- All versions of the survey could have been launched at the same time.

- A larger, more inclusive set of beta-testers could be identified.

- Our assumption that all aid workers want their voices heard needs questioning.

- Our means of making people aware of the survey need reassessment.

In the end, as they say “it is what it is” and the best that we can do is learn from the past so that we can make future efforts more robust and, yes, inclusive.

Next steps

Now that this exploratory phase is nearly done, where to from here? I have begun doing in-depth interviews with select respondents, but I suspect this will not yield any major revelations. I would very much like to probe more deeply into the lives of local aid workers and am open any discussions that could make that happen.

As always, please contact me with thoughts, feedback or snarky comments.

Follow

Follow