Job security and advancement possibilities

More results from the Jordanian humanitarian worker survey.

Not secure

We live in a world where certainty can be a scarce commodity, and in the Middle East, especially in the Levant, political volatility inevitably leads to rocky and tenuous economic conditions for most people.  Jordan serves as an international hub for many large INGOs, and those employed in the humanitarian sector make up a significant portion of the entire workforce. In this next section of the survey I examine perceptions about job security and advancement opportunities and, given the overall geo-politics of the region and in Jordan particularly, the results will surprise few.

Jordan serves as an international hub for many large INGOs, and those employed in the humanitarian sector make up a significant portion of the entire workforce. In this next section of the survey I examine perceptions about job security and advancement opportunities and, given the overall geo-politics of the region and in Jordan particularly, the results will surprise few.

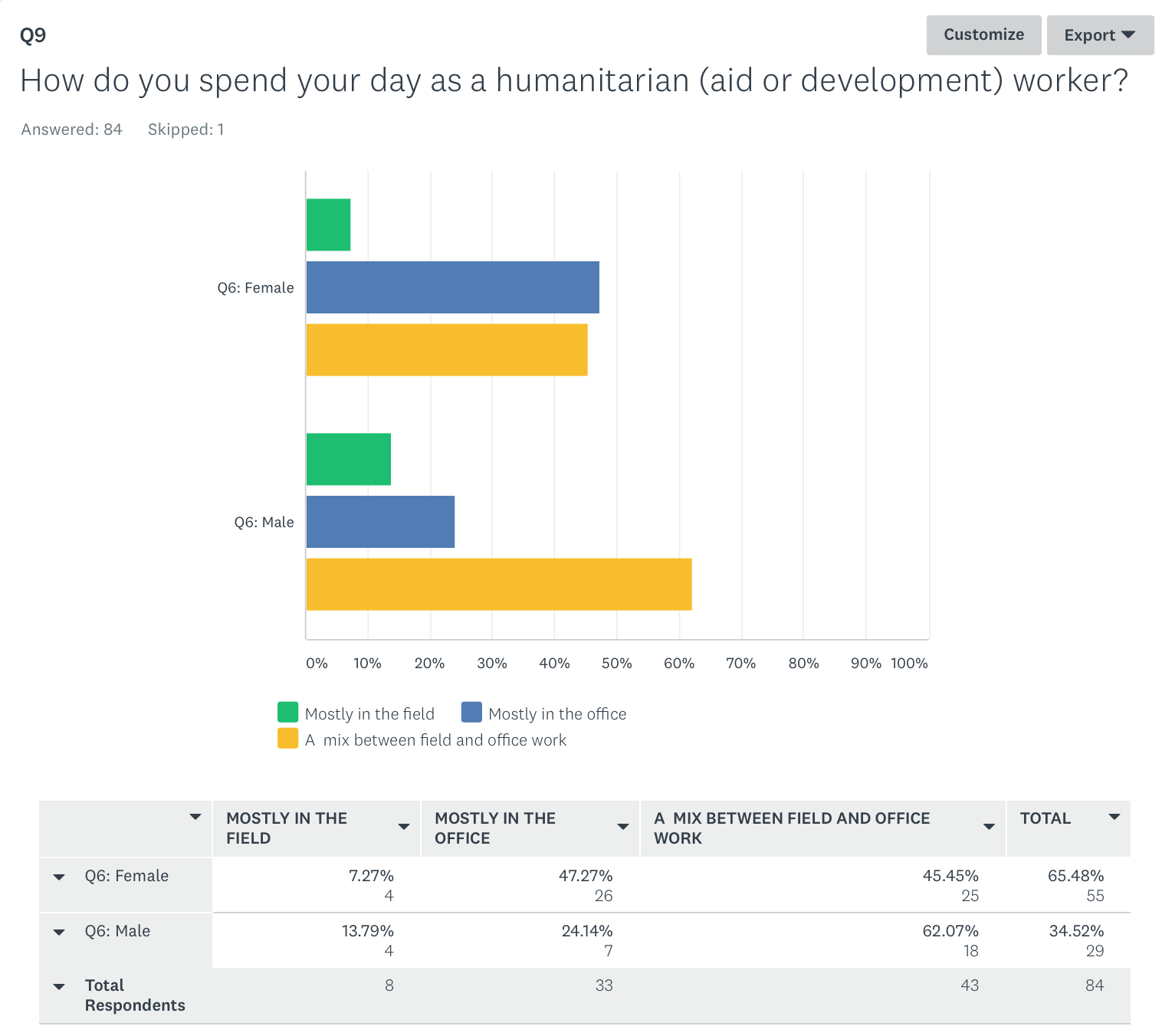

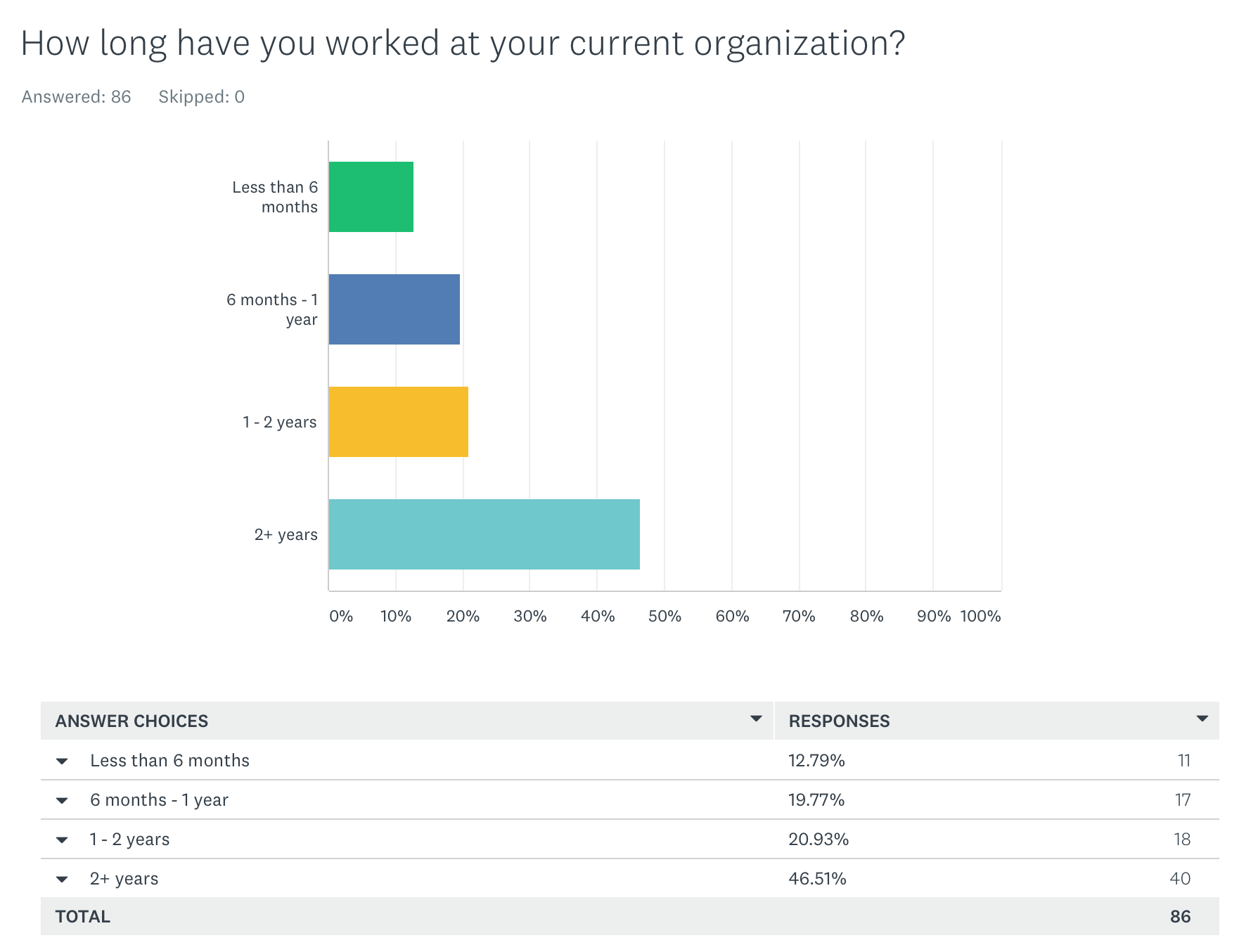

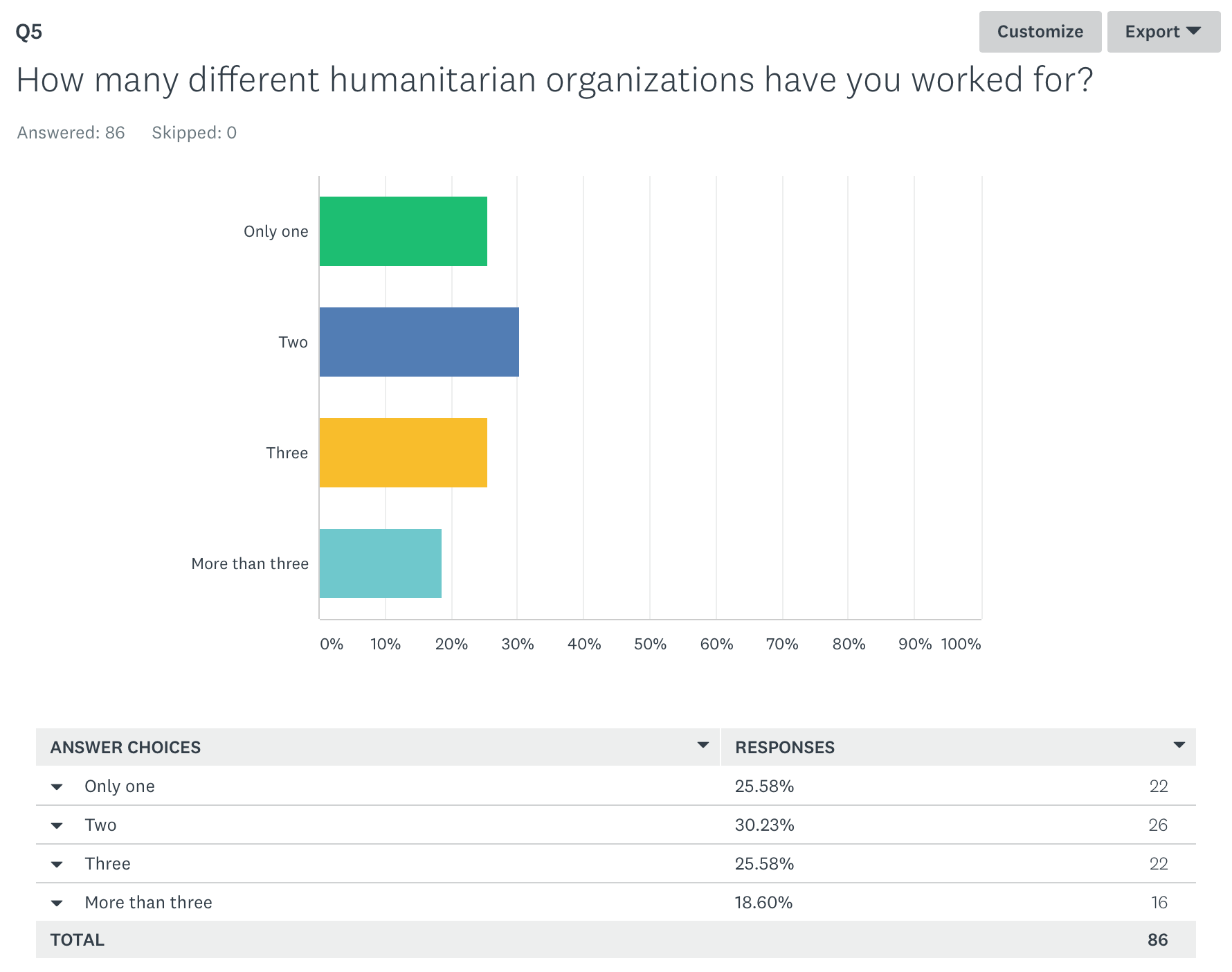

To preface this section it seems relevant to note that among this sample of Jordanians nearly half -44%- had worked for three or more organizations. There appears to be a good bit of lateral mobility within the humanitarian work force, and many national workers have experienced the organizational culture within a variety of INGOs.

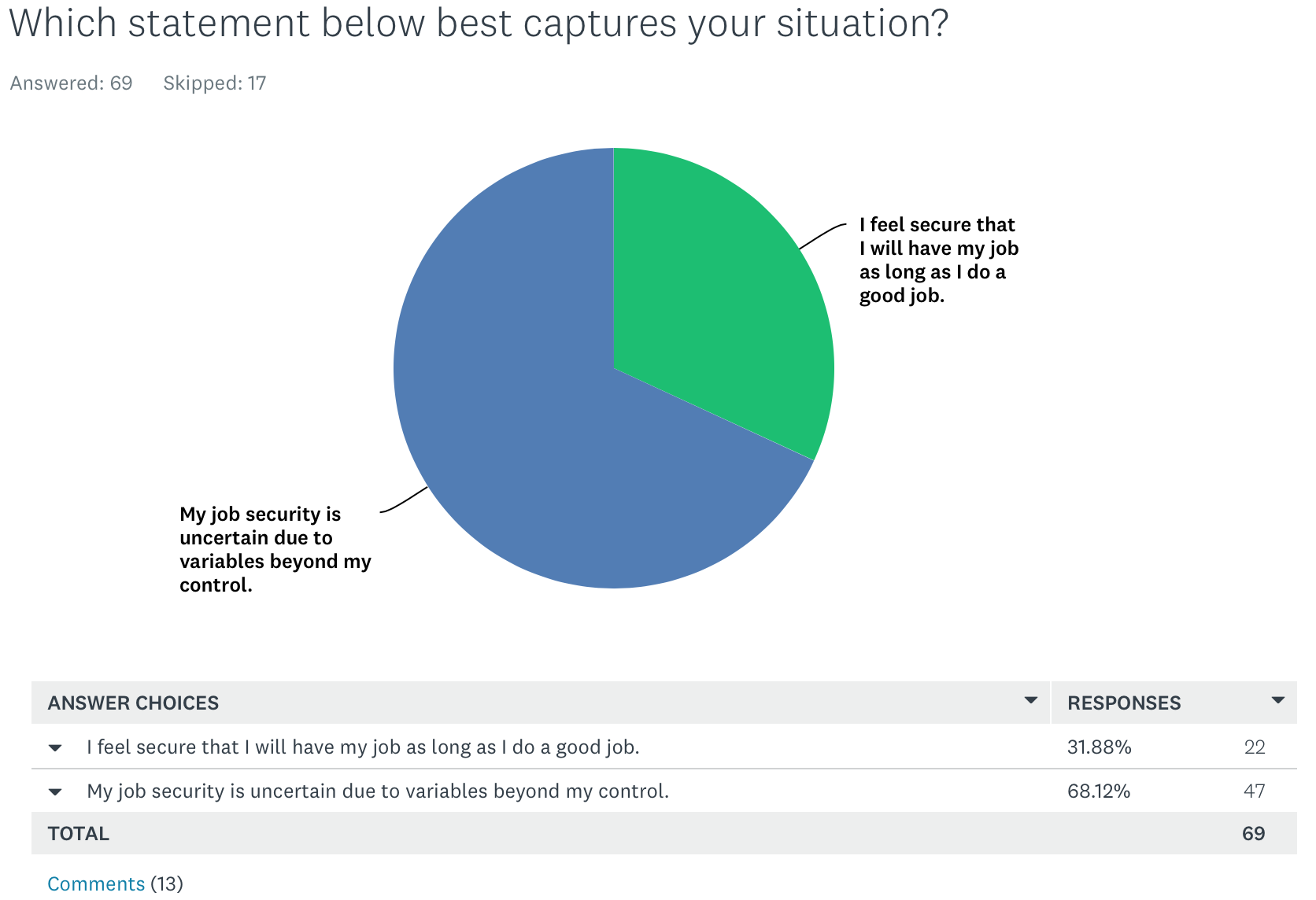

Very simply put, most of the respondents felt insecure in their jobs, with just over two-thirds indicating that “My job security is uncertain due to variables beyond my control.” Many respondents chose to add comments to this question, and a common theme runs through most of them. This first comment speaks for many, and points out the sad irony many have noted about the humanitarian sector in general, that an explicit goal is to rid the world of conflict and gross inequity and “work ourselves out of a job.”

“work ourselves out of a job.”

“Jobs in this sector generally aren’t secured and they’re project based, regardless of how experienced the person is, how many years the person spent as part of the organization, there will always be funding limits and one day most of the INGOs in Jordan might be out, and many will be unemployed.”

Perhaps looking more with a short term view one respondent stated,

“Refugees not going anywhere any time soon.”

Circling back to my previous posts commenting on the oft strained relationships between ‘national’ and expat’ workers, this respondent noted,

“The sector as a whole is unsecure due to shifting politics and shifting donor focuses. Also, I feel my job is unsecure due to shifting power-relations and politics in our organization. If we get more money, I might find myself replaced with an ‘international staff’.”

Of note is that females felt more insecure than males by a slight margin, 72% compared to 61% of the males.

Expat ceiling?

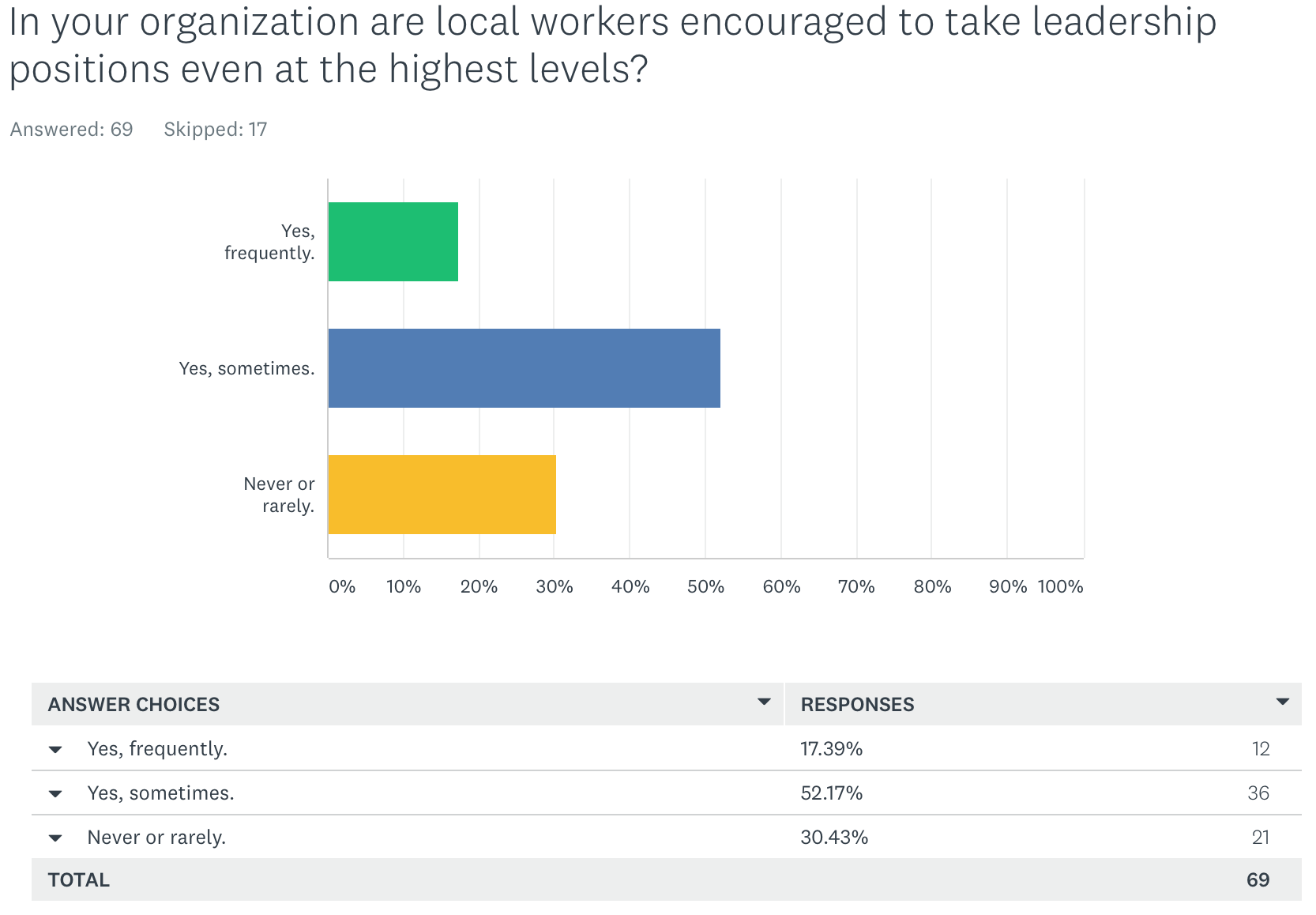

The next question probes the ‘expat ceiling’ asking, “In your organization are local workers

encouraged to take leadership positions even at the highest levels?” Looked at from a ‘glass half full’  perspective, the data could be read to say that most -70%- believe that leadership positions at the highest level are possible, ‘only’ 30% feeling that those pathways are ‘never or rarely’ open to them. The comments that were offered indicated a more sober, negative tone.

perspective, the data could be read to say that most -70%- believe that leadership positions at the highest level are possible, ‘only’ 30% feeling that those pathways are ‘never or rarely’ open to them. The comments that were offered indicated a more sober, negative tone.

“‘A white person will do it better’ – International NGOs.” said one. Adding more detail, a second respondent offers this.

“The senior vacancies are usually predetermined to be expat positions, therefore locals aren’t even given a chance to apply. The budgeting (salary planning) and all of that takes into account that a certain position is international, and the position would even have a different color on the organigram, it sends a message to the locals ‘there’s your limit, after this position you can’t have anything more’. Moreover, at many times I’ve seen that even when two managers have the exact same responsibilities, experience, and are on the exact same level, but one of them is local the other is international, the opinion of the international manager is heard more, respected more and has automatically more influence.”

There were several pity responses echoing this exact sentiment:

“99% of high positions are occupied by expats.”

“Most senior level jobs aren’t open to local staff.”

“Senior positions are locked to non Jordanians.”

This comment below makes explicit how some Jordanian humanitarians frame the issue. Though specific to one organization, this veteran male uses the frank language of discrimination to describe the situation.

“This question is at the heart of the discrimination/problem. As I explained in previous answers, there are levels where local staff are not allowed to apply to! In my organization only staff up to level 8 are allowed to be Jordanian. But the levels go up to level 12 (the country director) and all these four higher levels are exclusively for expats, with 8 even being mostly for expats and rarely for Jordanians.”

Limiting factors

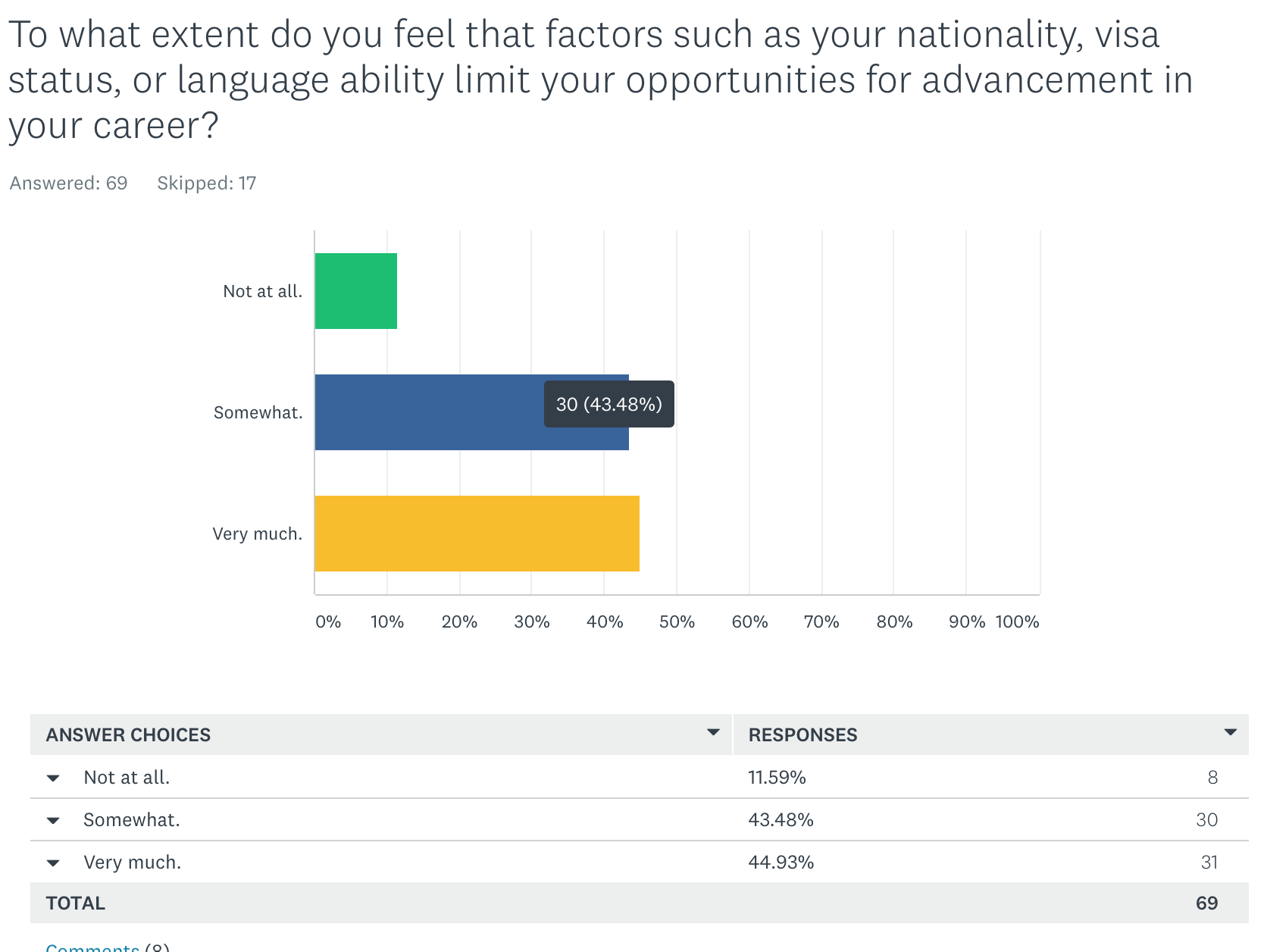

The next question on the survey allowed respondents to comment on factors that might limit their mobility. I asked, “To what extent do you feel that factors such as your nationality, visa status, or language ability limit your opportunities for advancement in your career?”

The vast majority -88%- felt that these factors limited career advancement. There were comments on each of the three prongs to this question.

Regarding nationality, one said,

“I think it mostly falls under nationality, once you’re internatioanl then you’re treated differently, you get higher pays, more senior positions, much more benfits, etc. Therefore as a Jordanian passport holder, the treatment isn’t the same, I don’t have the same access as international people have.”

Another respondent makes the global comment that,

“In this sector you find favored nationalities regardless of the competencies in selecting candidates, which will block you getting an international experience that can help to develop your career.”

Specific to visa status, the bureaucratic and financial factors were seen to play a part. This respondent notes this but also is vocal about the discrimination aspect.

“NGOs don’t want to go through the hassle of delayed visas and paying visa fees, and they don’t think nationals have the capacity to take big steps in their career and they don’t support the capacity building of these employees.”

The third factor mentioned in the question prompt -language ability- is perceived to be part of the cocktail of factors limiting advancement. This veteran female humanitarian worker puts it this way.

“It’s a rarity that non-English speakers get to higher levels in this sector. Even assistants and officers are required to have English language competencies and are then subjected a series of courses to learn English better so they can move up. Of course ‘Western’ nationalities have advantage over Jordanian nationality holders as you go up in the career ladder. Although connections and the country where you were educated also matter to Jordanians.”

Take away thought from the above?

The survey data that I’ve reviewed above compliments and extends the many interviews with Jordanians working in the sector that I had both while in Amman and via Skype since that visit. Jobs in the humanitarian sector are frequently contract to contract, with many workers moving laterally -though sometimes vertically- from one organization to another. To state the obvious, those who want to affect positive change regarding the perceptions cited above face significant challenges; there is no ‘silver bullet.’

The broad goal of further ‘nationalizing’ the humanitarian sector will at best, I’ll assert, more forward apace with the forces of economic and political globalization, and not much faster.

Please contact me with comments or questions via email.

You can access all of my posts related to Jordanian humanitarian workers here.

Follow

Follow

One year ago I began making contacts in Jordan, and established a partnership with several national senior level staff members at a major INGO. I was subsequently hosted on a visit to Amman to workshop with small focus groups early drafts of a survey intended for Jordanian aid workers. After nearly two dozen revisions using the feedback from both Jordanian aid workers and fellow researchers, a final version was made live in November 2017. On the advice of my colleagues in Jordan, the survey has remained open until now. Using the same methodology as my previous research, information about the survey encouraging Jordanian staff to participate was circulated using a variety of social media vectors.

One year ago I began making contacts in Jordan, and established a partnership with several national senior level staff members at a major INGO. I was subsequently hosted on a visit to Amman to workshop with small focus groups early drafts of a survey intended for Jordanian aid workers. After nearly two dozen revisions using the feedback from both Jordanian aid workers and fellow researchers, a final version was made live in November 2017. On the advice of my colleagues in Jordan, the survey has remained open until now. Using the same methodology as my previous research, information about the survey encouraging Jordanian staff to participate was circulated using a variety of social media vectors.