“Probably the reason I stayed in the sector is because I wanted to perform my responsbility towards the marginalized and act as a counter-force to the corruption, mismanagement, and injustices I saw in the sector.”

– Jordanian female aid worker employed by a large INGO

Why are you a humanitarian (aid or development) worker?

Even a casual read of the large body of ‘tell all’ or memoir books by current or former aid workers leads to an obvious common denominator. Virtually all of these works address the question, “why I got into this field in the first place.”

In the social sciences, answers to most ‘why’ questions are generally complicated and demonstratively non-binary. For most ‘why’ questions there is typically a hierarchy of answers, some more important than the others. When allowed the opportunity via open-ended comment boxes, respondents will, in various phrasings, say that their reason for doing something is based a blend of many variables, some of which are ‘rational’ and others very personal and emotional.

In the social sciences, answers to most ‘why’ questions are generally complicated and demonstratively non-binary. For most ‘why’ questions there is typically a hierarchy of answers, some more important than the others. When allowed the opportunity via open-ended comment boxes, respondents will, in various phrasings, say that their reason for doing something is based a blend of many variables, some of which are ‘rational’ and others very personal and emotional.

Here is the blog post I made a discussing the data from over 1000 (mostly ‘expat’) aid and development workers. An astounding 72% (596 out of 826) of those answering the closed ended question “Which statement bellow best describes your primary reason for becoming an aid worker?” chose to add some elaboration in the comment box offered. I asked a similar question with my survey of Filipino aid workers, and here is the post based on those data.

How did the Jordanian’s respond?

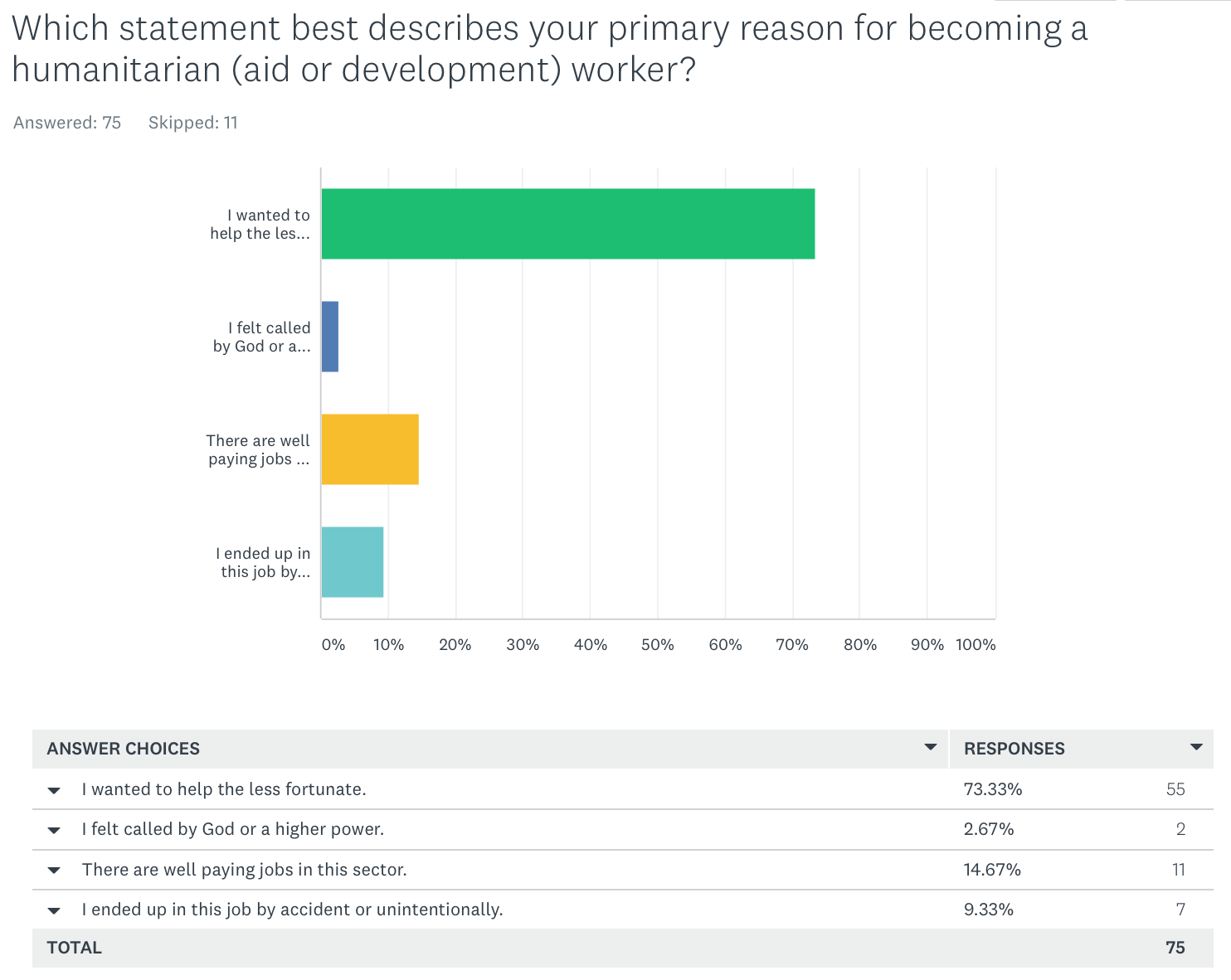

The survey question “Which statement best describes your primary reason for becoming a humanitarian (aid or development) worker?” allowed for four options and encouraged the respondent to elaborate on their choice. Those responding chose overwhelmingly -nearly three-quarters- “I wanted to help the less fortunate.” The second most frequent response, “There are well paying jobs in this sector.” yielded nearly 15%. This response option was added based on interview data with Jordanian aid workers during my field work in Jordan and later affirmed by numerous Skype interviews as the survey was fine-tuned. Given this methodology in crafting the response categories I had assumed -wrongly- that a larger percentage of respondents would have chosen this option.

Interestingly, a paltry 3% chose “I felt called by God or a higher power.” As a comparison, in the Aid Worker Voices survey 6% chose that option, and in the Filipino survey 4% indicated similarly.

Interestingly, a paltry 3% chose “I felt called by God or a higher power.” As a comparison, in the Aid Worker Voices survey 6% chose that option, and in the Filipino survey 4% indicated similarly.

What seems universal in my three surveys of aid workers thus far is that they come into the occupation not called by their religion but rather by basic human caring and altruism, wanting to help the less fortunate.

In the comments were some passionate voices. Here’s two, both by females.

“Fighting for women’s rights and gender equality is my passion, study and profession in life.”

“[My reason for becoming a humanitarian worker is] Really a mixture of options 1 and 4. Probably the reason I stayed in the sector is because I wanted to perform my responsbility towards the marginalized and act as a counter-force to the corruption, mismanagement, and injustices I saw in the sector.”

There was a mildly interesting gender difference in answers with 79% of the females indicating they came into the sector to ‘help the less fortunate” compared to ‘only’ 63% of the males indicating same. More than twice as many males than females indicated they came to the field ‘accidentally or unintentionally.’

Like your job?

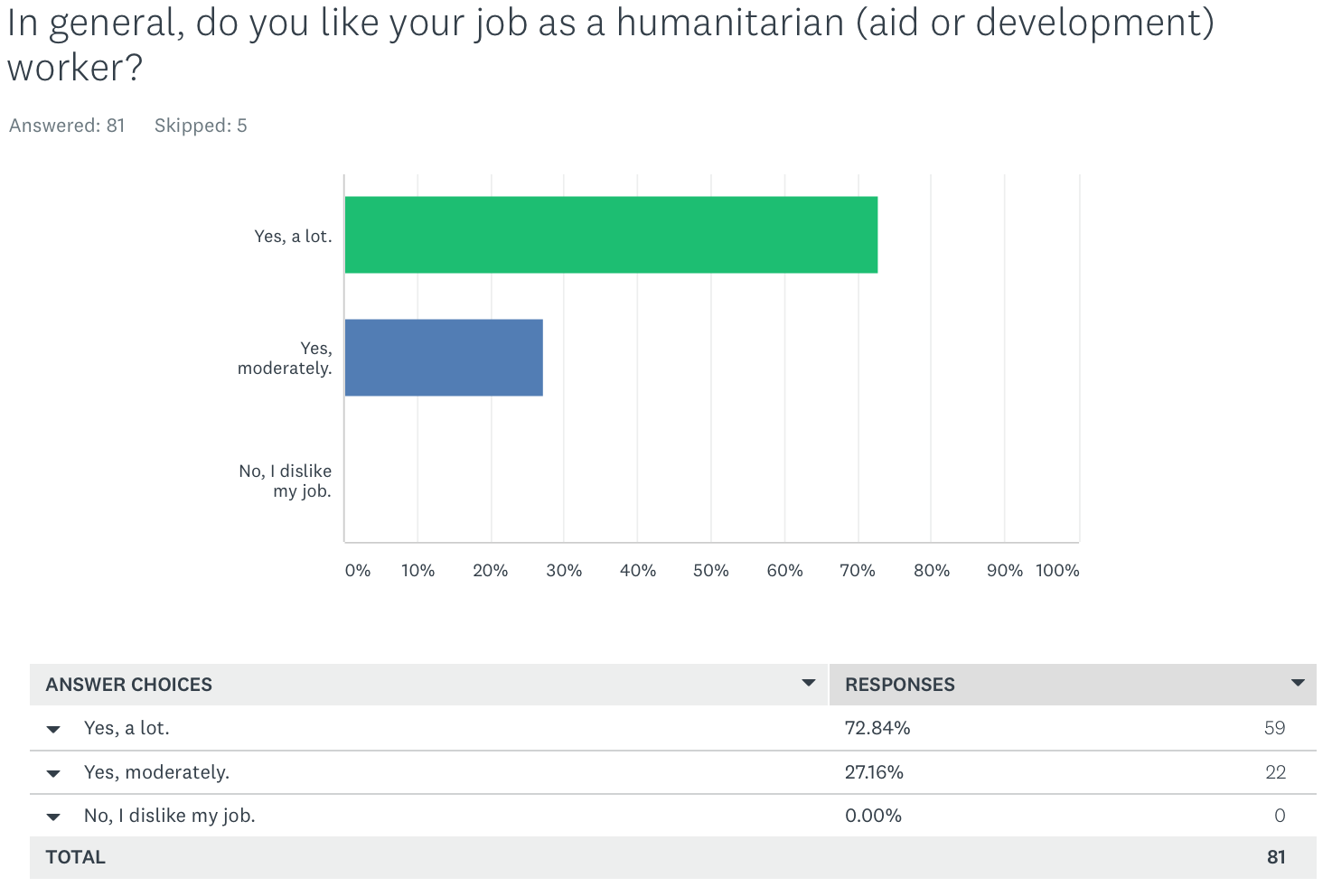

Once in the sector, do Jordanians report being satisfied with their jobs? Overwhelmingly, yes. Here are the data indicating that 100% of the respondent like their job at least moderately, with none indicating dislike.

A few chose to comment on their responses, and a theme among those was making qualifications to their closed positive ended response. Here are some examples.

“It can be very hard and frustrating at times, no job is perfect. This one needs a special kind of  patience.”

patience.”

“I love my job, but there are so many things that are lacking that can really improve my work situation.”

“I find working with children and youth is really gratifying, reinforcing their resilience and learning from them and empowering them to demand more accountability from organizations. I find it frustrating that the heirarchy of power and inter-identity policitics have shaped this sector in very negative ways and have — in some instances — rendered the marginalized even more so and more voiceless.”

This last comment by a female veteran aid worker articulates a significant issue, namely that sometimes the workings of the sector can have impacts which move the needle in a negative direction.

End note

I keep encountering variations of the word ‘marginalize’ in respondent comments, three times in just this post. Implicit in the word ‘humanitarian’ is that all humans have equal value, and to work in the ‘humanitarian sector’ is to be part of an effort to move toward a world where all humans are treated with dignity. Efforts that lead to marginalization are inherently racist, inferring that some humans are worth more than others. I point this out as events in the Levant -especially with reference to the plight of Palestinians– indicate that there are many in political leadership who’s actions only serve to minimize dignity.

‘humanitarian sector’ is to be part of an effort to move toward a world where all humans are treated with dignity. Efforts that lead to marginalization are inherently racist, inferring that some humans are worth more than others. I point this out as events in the Levant -especially with reference to the plight of Palestinians– indicate that there are many in political leadership who’s actions only serve to minimize dignity.

More results very soon. In the meantime email me any comments.

Follow

Follow