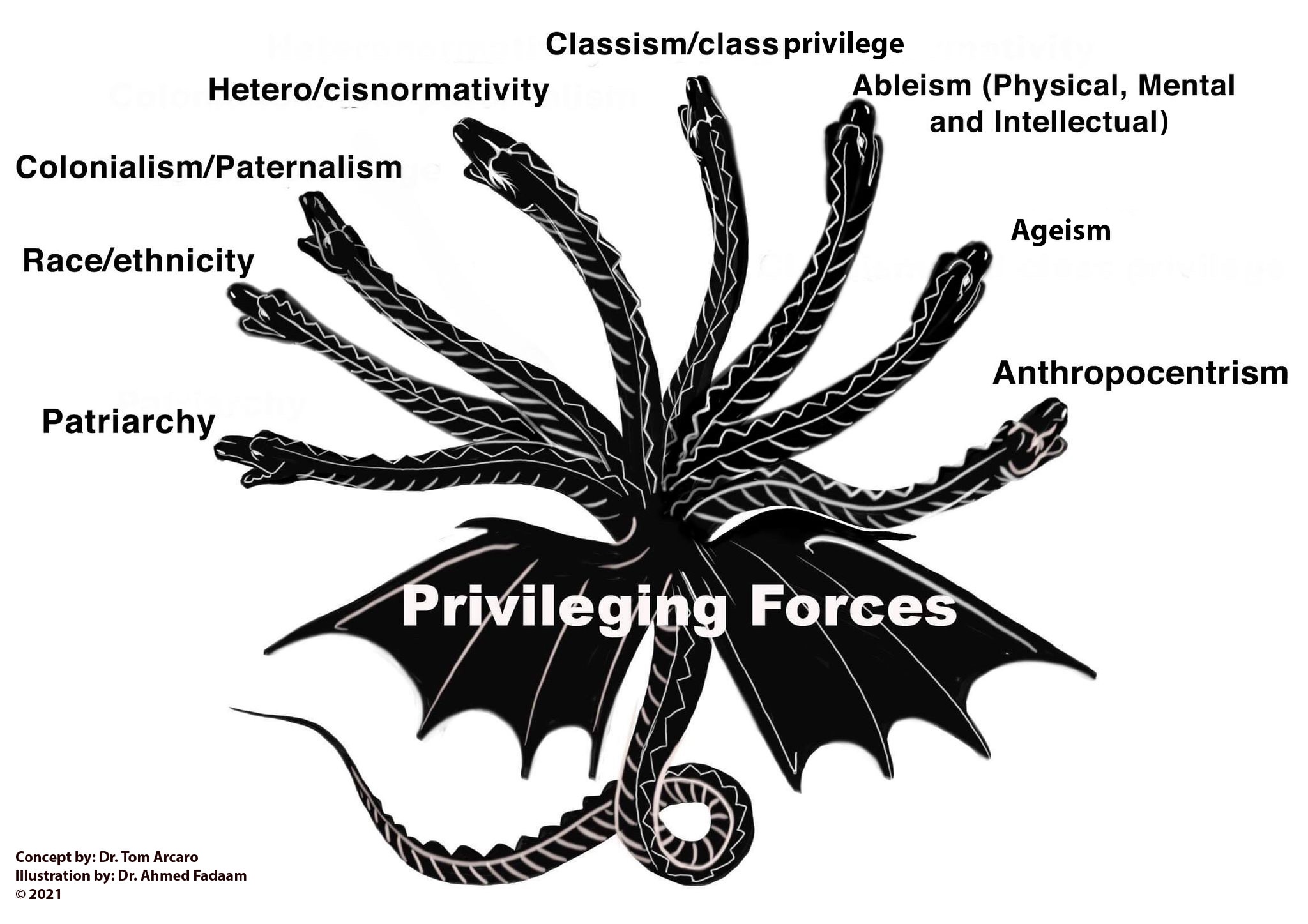

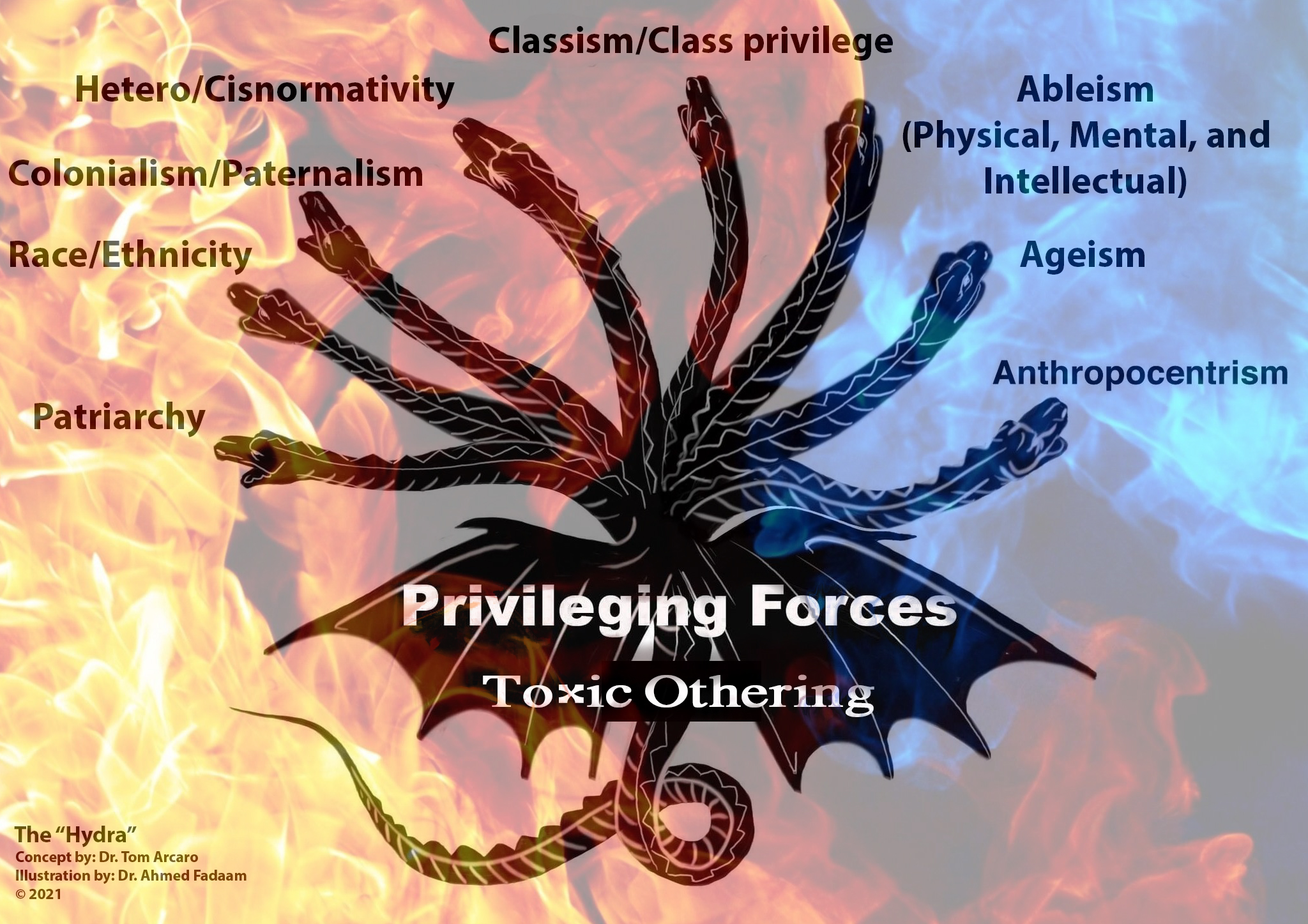

“Part of the reason we have not seen the Hydra defeated is that we attack the heads one at a time instead of learning from history that they are all connected.”

-Grant Mitchell

SOC 131 student

Bringing the Hydra to class

Student reactions to the Hydra

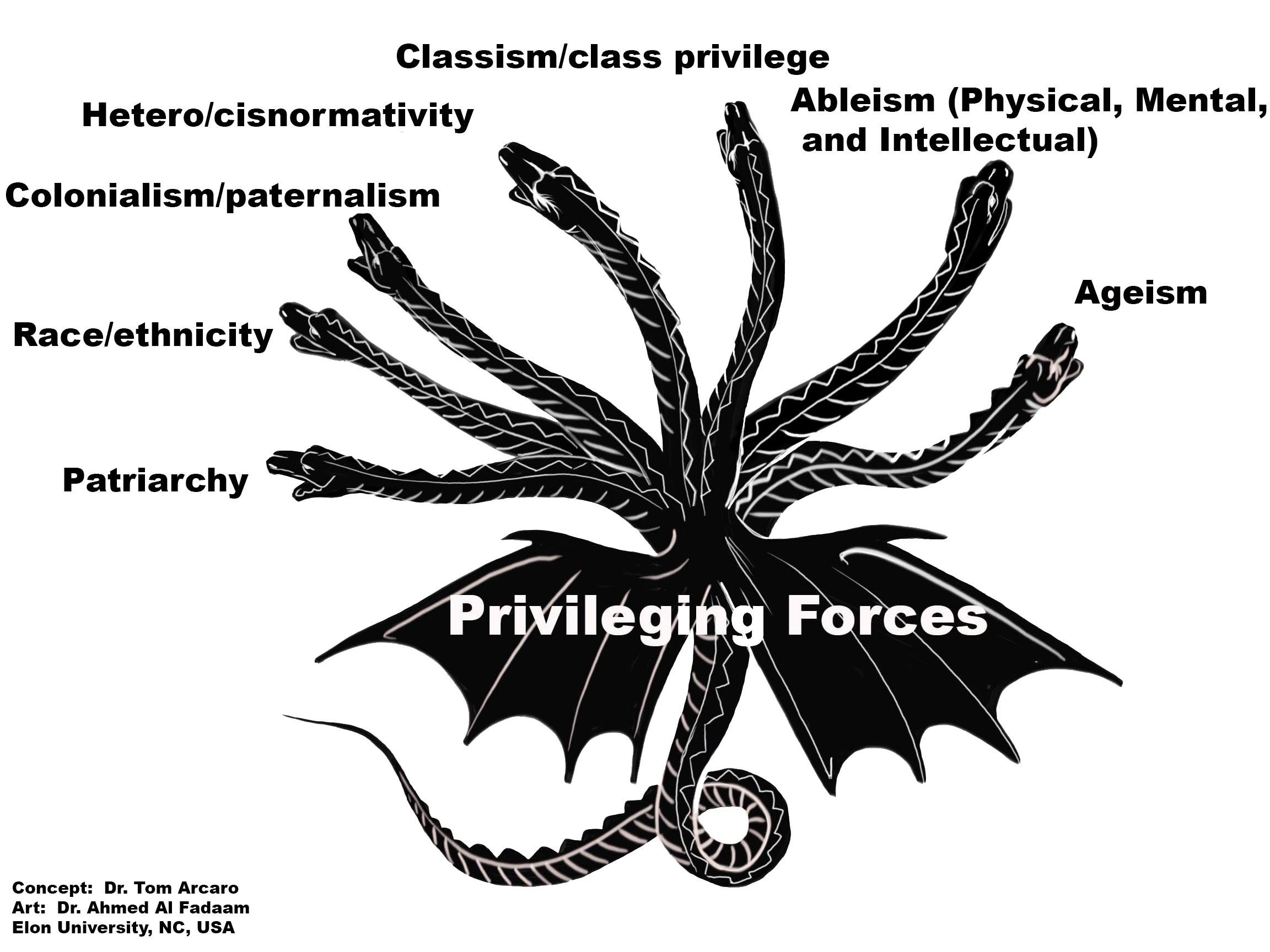

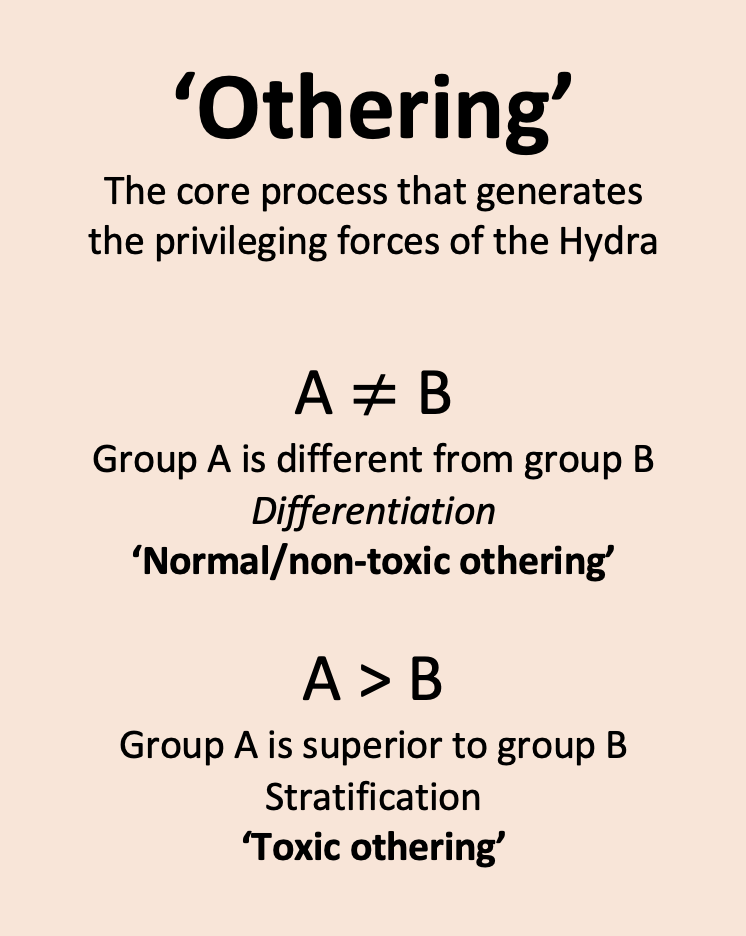

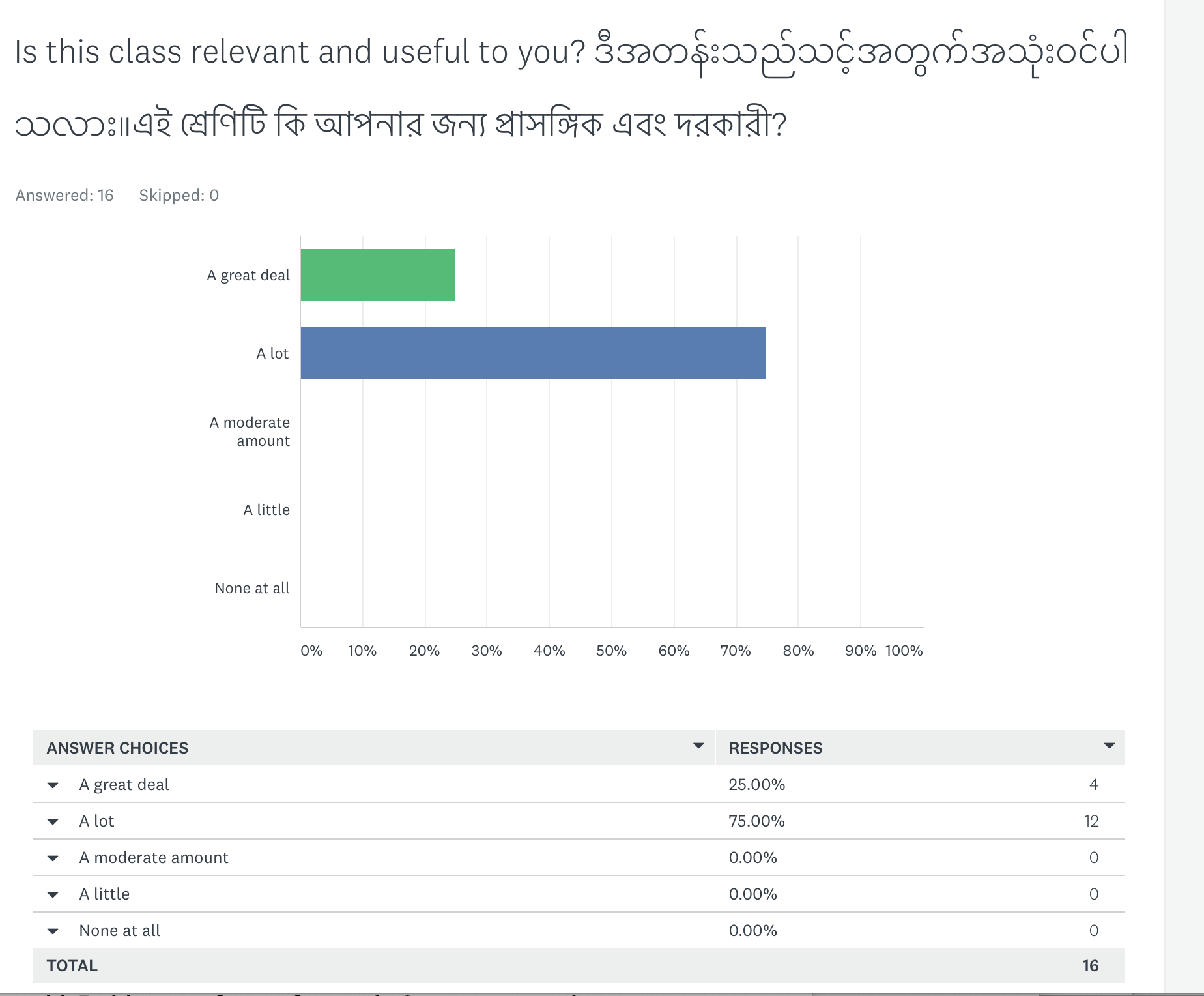

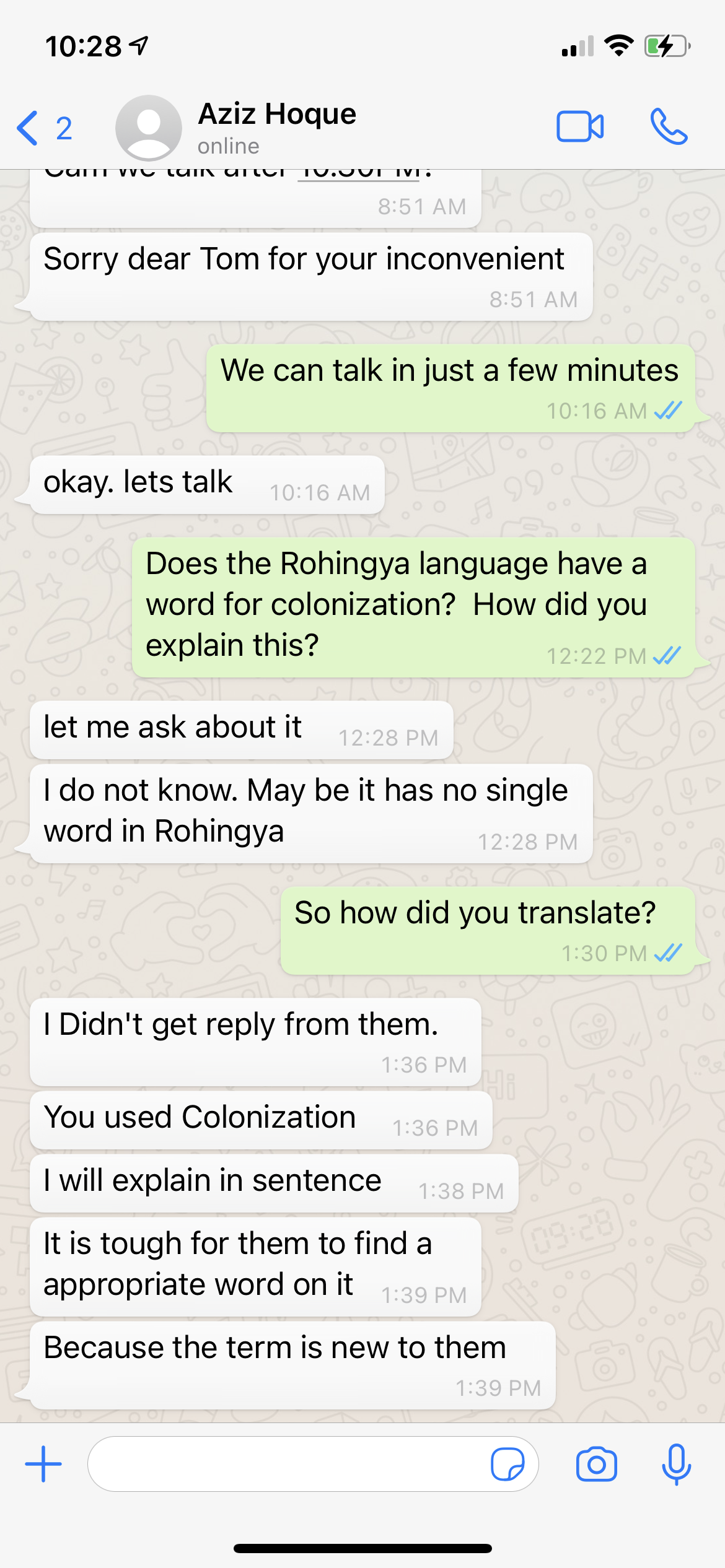

I have been using my Hydra posts as a teaching tooling since the Fall of 2019. Every semester I’ll explain the idea in class and then have my students read about the Hydra, using it in some manner to help deepen their understanding of core course concepts like colonialism, racism, classism, and sexism. To the present I have used this model in over a dozen classes, and each time my students push me to expand my thinking and to reconsider and deepen aspects of the Hydra’s impact. I owe a massive debt to all my students these last several semesters.

This summer I taught online ‘Sociology Through Film’ and was blessed with many very good students who, as a group, embraced the Hydra concept quickly and enthusiastically. Below you’ll read what several students had to say when I proposed they find and discuss a film which addressed one or more of the Hydra heads. I was impressed by the variety of the films on which they chose to focus and, in general, how well they used some of out course content.

content.

Many thanks to student Trinity Black for editing these essays for clarity and content.

The Hydra in Film

Elon University

Summer I 2021: SOC131 Sociology in Film

Introductory Statement

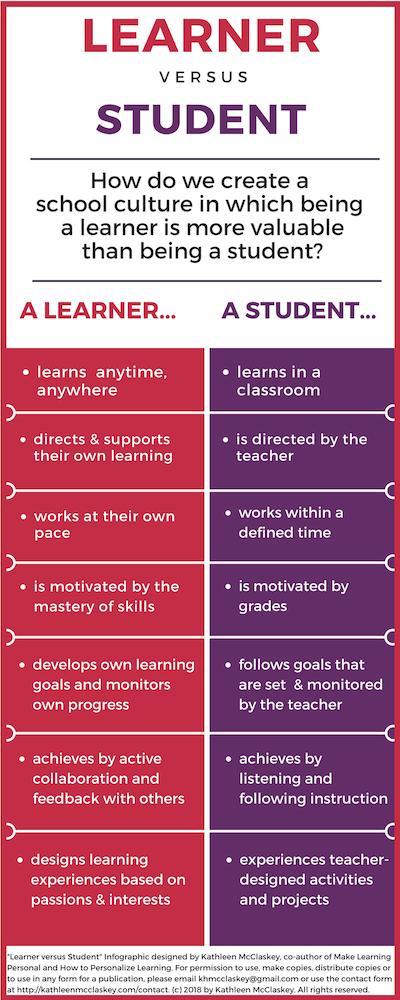

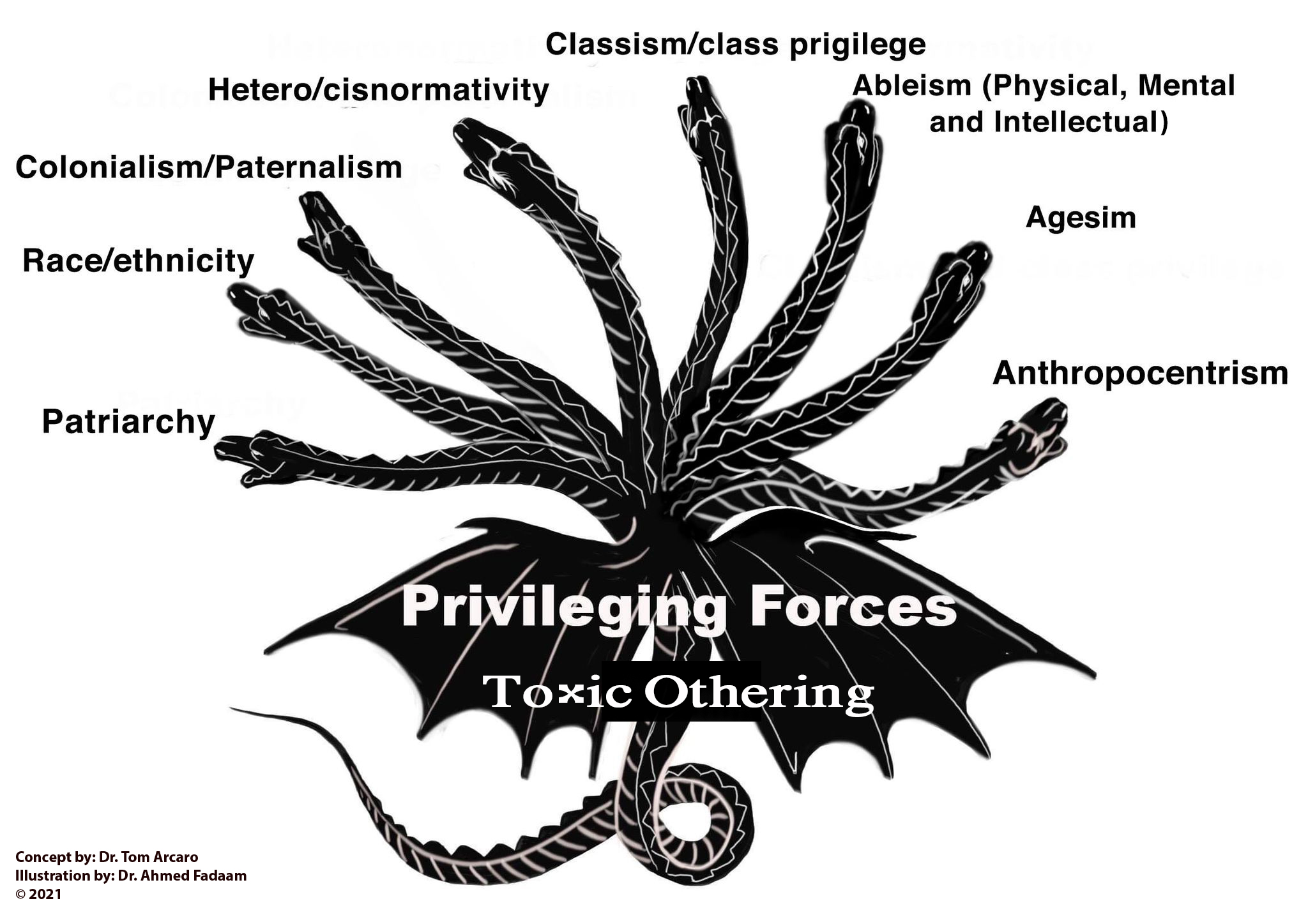

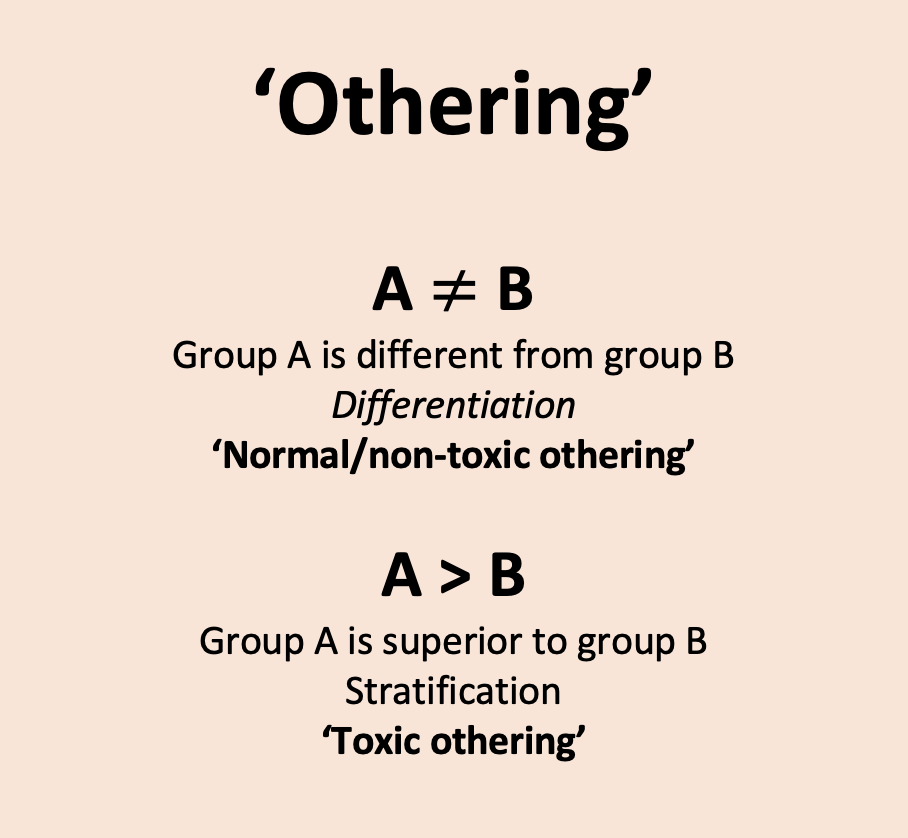

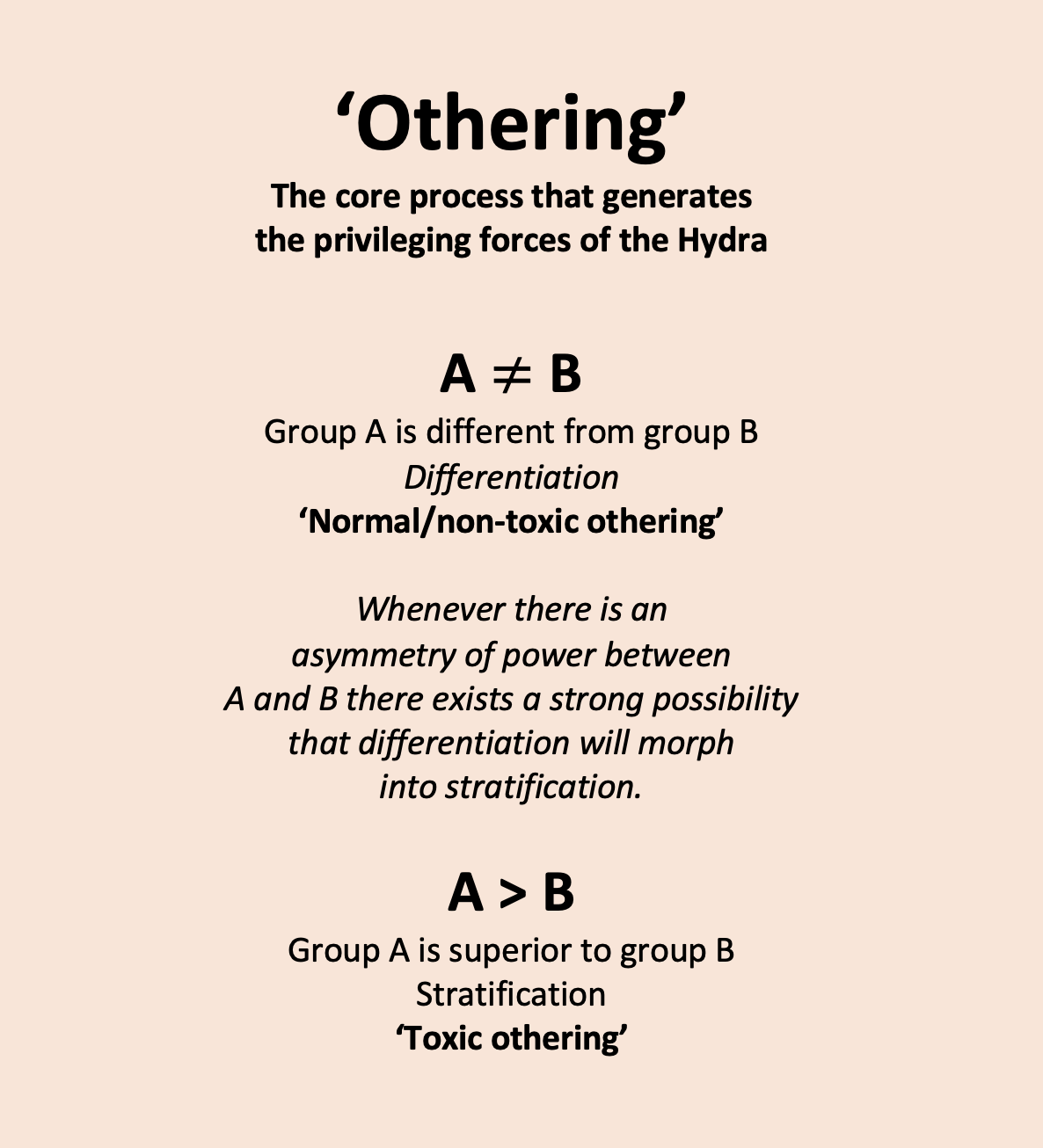

By Caroline Borio

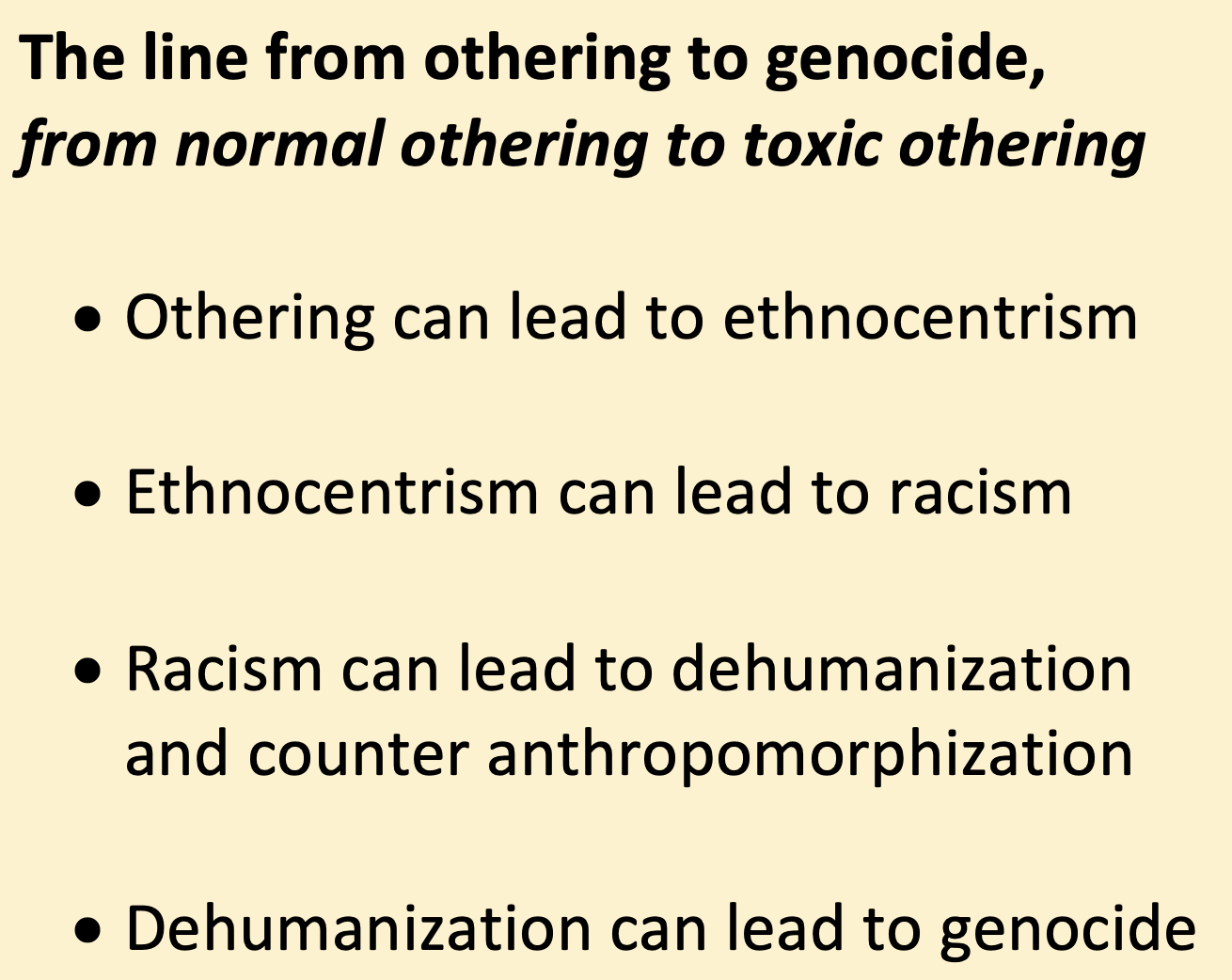

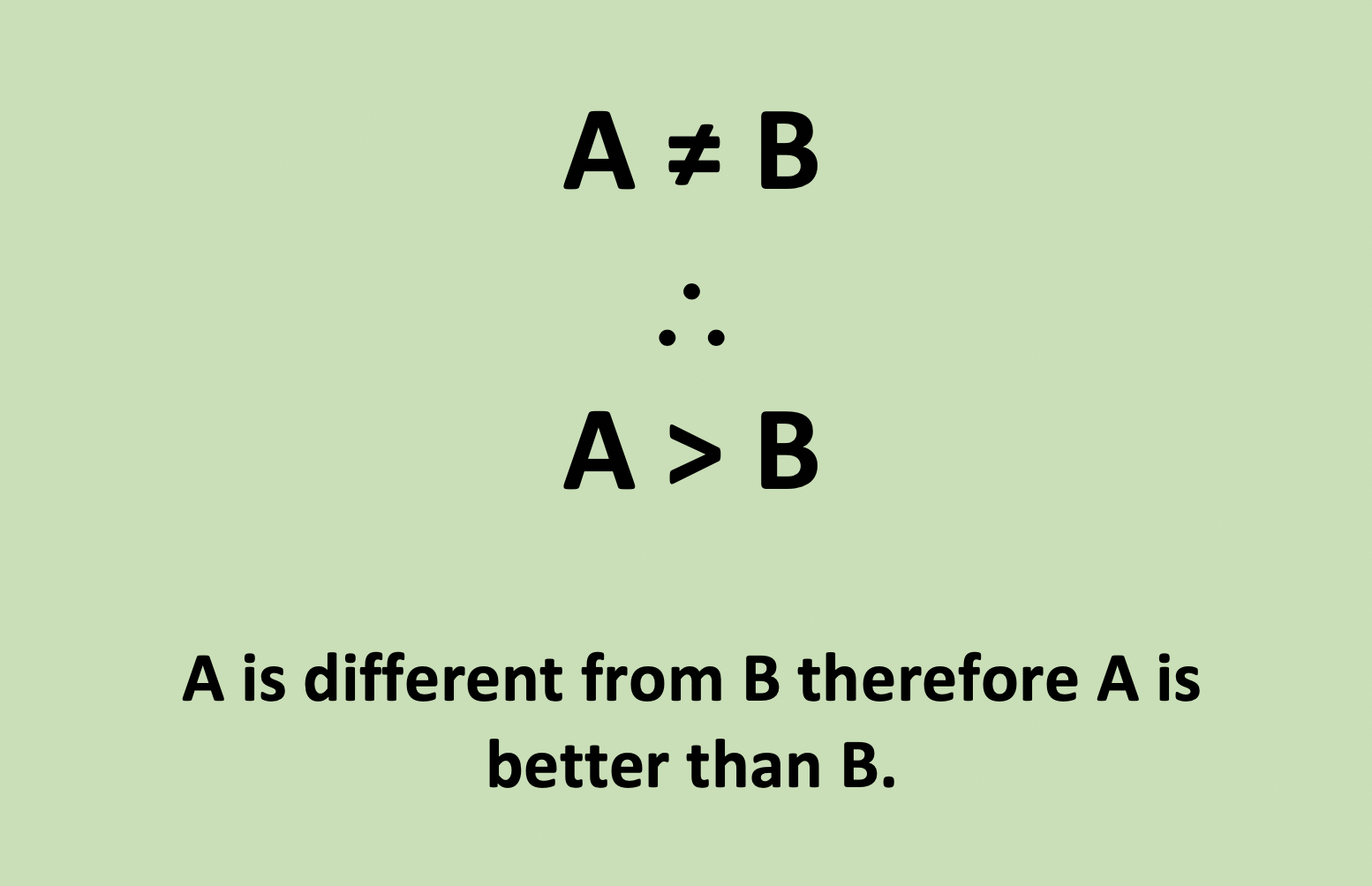

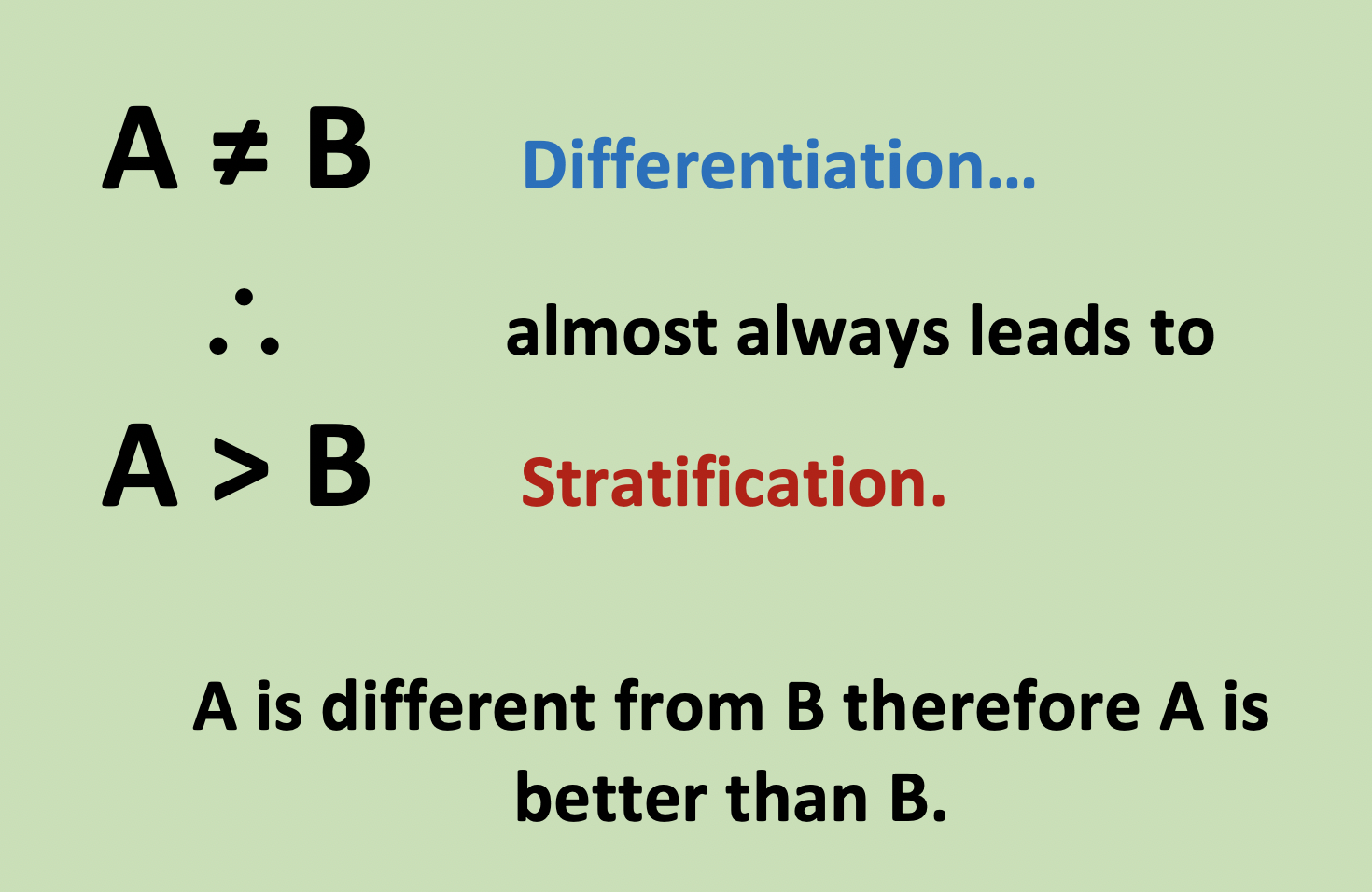

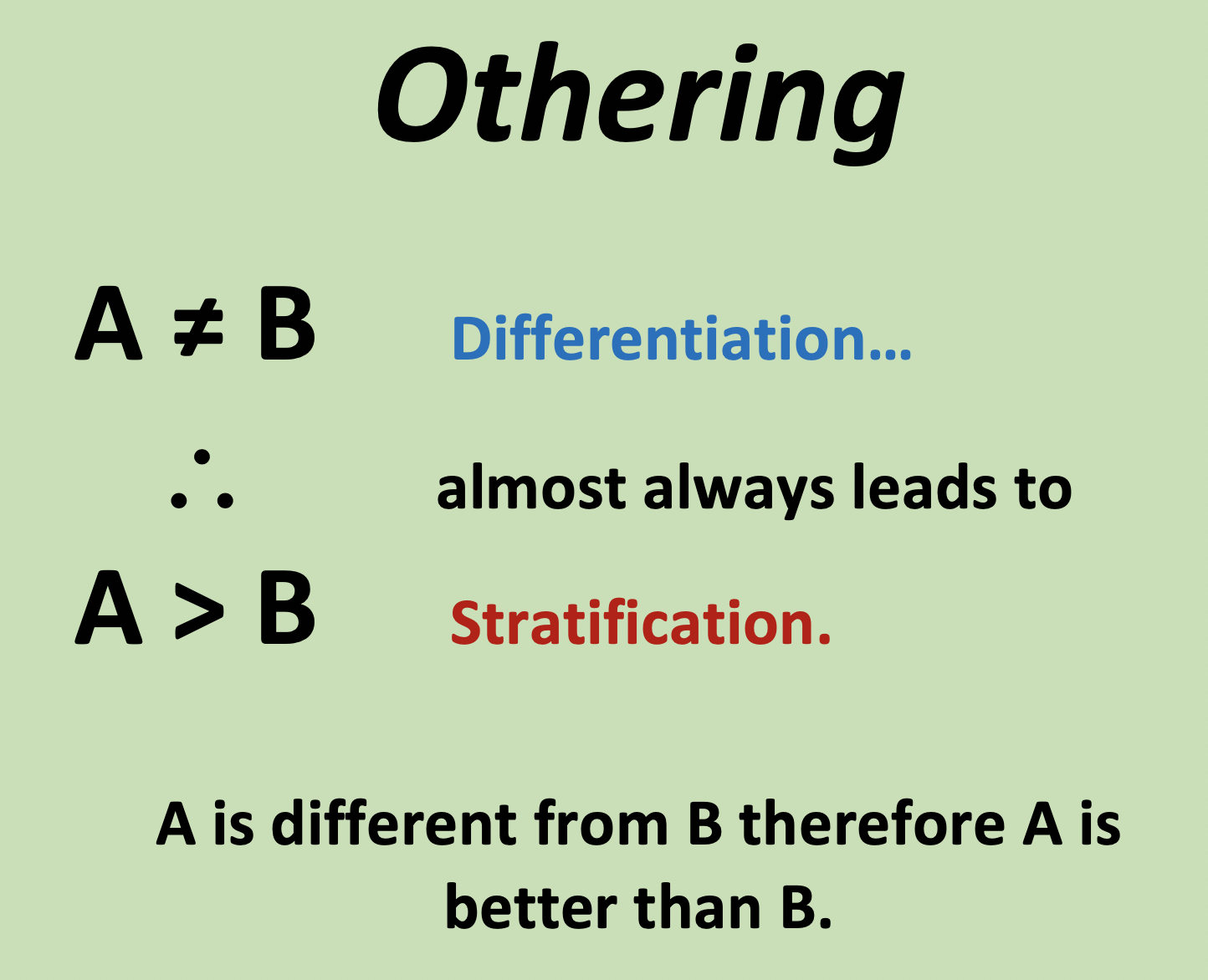

As a part of Dr. Arcaro’s Sociology Through Film course, my fellow classmates and I were tasked with reading and understanding Dr. Arcaro’s blog posts on The Hydra metaphor, and applying that knowledge to film analysis. From the first class discussion after we read Dr. Arcaro’s blog posts, it was clear that the entire class quickly embraced the idea and was able to apply it to film analysis, and to both historical and recent events in the world around us. In that first discussion, I recall hearing my classmates explain how forces such as racism and sexism clearly intersect, and all of us at once understood why it is important to fight against not just one, but all of these forces since they all stem from the same source of “othering”. It was clear from the beginning that the Hydra is an incredibly useful tool for students when trying to understand privilege, and the intersectionality of these privileging forces in the world.

In the following chapter, you will see the writing some of us completed when we applied the Hydra to our study of Sociology through film. Each of us chose one of the eight heads of the Hydra on which to focus, and found a film that centered around that particular privileging force. After watching the film and identifying the significance of the privileging force within the film, we were asked to write a blog post that applied the idea of the Hydra to our film. This blog post was to consist of a summary of the Hydra metaphor, a description of our chosen privileging force, and how our selected movie sheds light on that privileging force. I had the privilege of reading my classmates’ blog posts, and each and every one of them provided a clear depiction of how their movie explored their privileging force, and why this was significant to the film’s overall purpose. Through our blog posts, I recognized how the Hydra concept can be a useful too towards recognizing privilege, intersectionality, and how we can approach the fight against these forces in order to create a more equitable and just society.

“Victoria and Abdul” (Colonialism/Paternalism)

By Grant Michael

The privileging force I’m examining is colonialism/paternalism and the movie I chose to tie into it is Victoria and Abdul. This movie focuses on the head of the British monarchy in the late 1800s, Queen Victoria, and her friendship with a common Indian man named Abdul. Through this lens, we get to see a lot of the power struggles between the queen and her subordinates, and the view on the larger colonized British Empire. Colonialism is “the practice by which a powerful country controls another country or other countries.” (Colonialism) I would like to add that other definitions usually also include “to exploit its resources.” Paternalism is “a system under which an authority undertakes to supply needs or regulate conduct of those under its control in matters affecting them as individuals as well as in their relations to authority and to each other.” (Paternalism) This basically means the people in power tell those under their power what’s in their best interest, with an almost “we-know-better” mentality. This movie, while on the surface seems to be about the relationship between Queen Victoria and Abdul, gives a good glimpse into the mindset and power struggles of these privileging forces.

In the movie, we see Queen Victoria in her last year of rule. The movie portrayed her well as someone who loved to rule, but at the same time knew very little about the world outside of her royal life. All the high-class members of British society we meet know very little about India but speak of it and its people as lesser compared to them. The queen, despite being its ruler, hadn’t ever been there. They all have this idea that they know better than the people they rule, however they’re highly unqualified to tell Indians how to live their lives halfway across the globe.

The most enlightening part for me was how everyone had made judgments about the Indians long before ever meeting someone from that part of the world. He is called “the Hindu”, even know he is Muslim. He also must teach the Queen “Indian,” despite there being thousands of languages and dialects spoken in India. The queen knew next to nothing about India or its culture, and it was honestly very surprising to see someone like the Queen taking on a commoner from India and learning from him, since it doesn’t fit the monarchy’s image. I think it was a good lesson; however, the paternalistic attitudes of the rest of the British stopped them from seeing Abdul as someone who could add any value to their lives. I’m sure most of the rest of the British empire felt this way, too. Even now, there is a feeling of personal superiority the British hold over others. This was only one country in an empire that ruled over 58 countries, so imagine how little the queen could have known about any of the rest she ruled. These discriminatory forces are what many empires are built from.

After watching the movie, I sat down to write this blog entry, and took notice of the other heads of the Hydra I saw. I could find an example of almost every privileging force in the film. This idea that all these forces exist alongside each other means you can’t just kill one head on the Hydra, you must kill them all to truly defeat it. The force of colonialism can seem far above us as individuals, but it’s up to us individuals to see the flaws within these systems, and advocate against them. I think paternalism appears very prominently in the movie, and it can remind us as to not make choices for people who are in groups we aren’t, as Abdul knew things about the world the others barely comprehend.

“My Beautiful Laundrette” (Hetero/Cisnormativity)

By Trinity Black

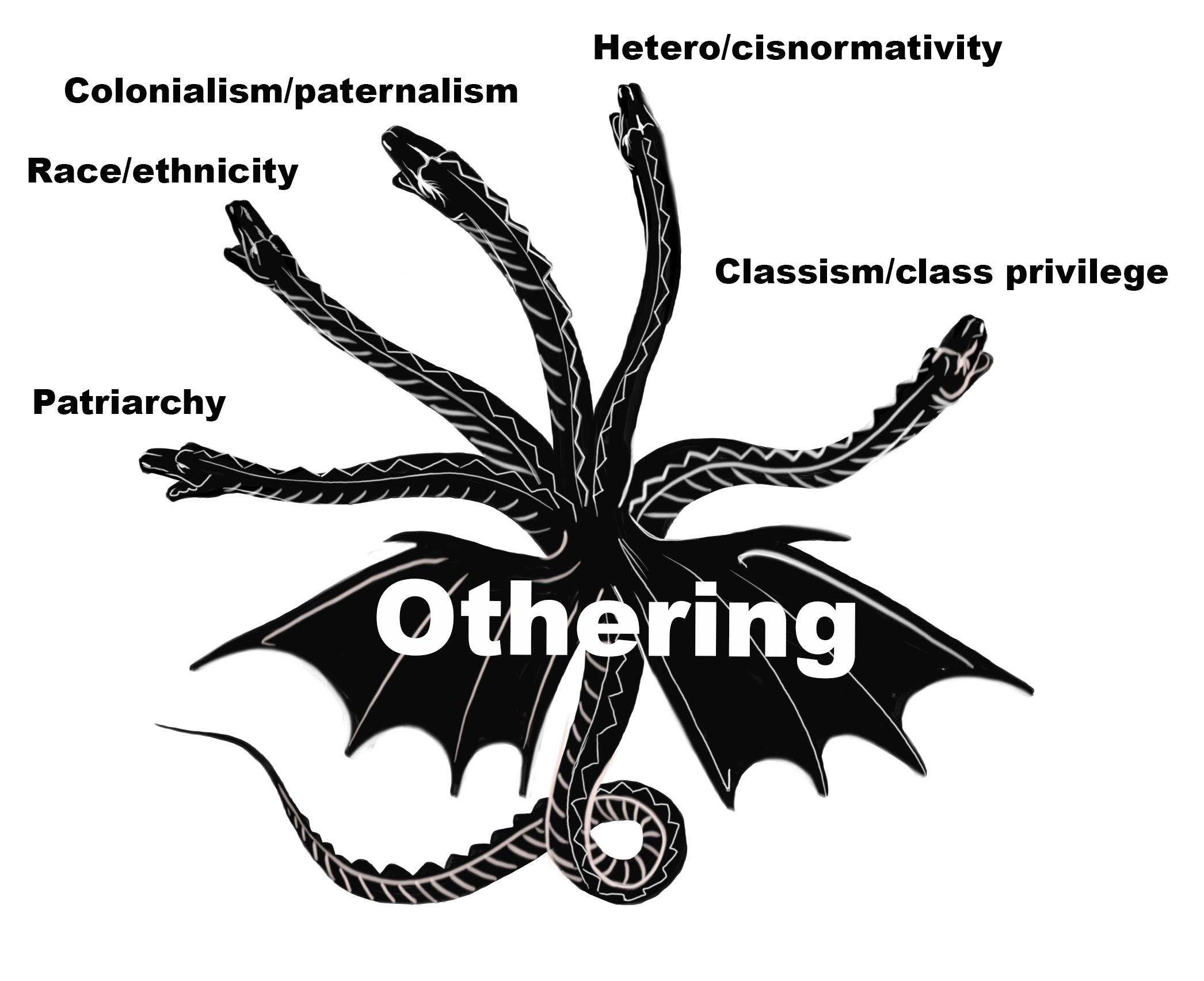

The Hydra metaphor is a way of understanding all the privileging forces at play in our society and how they’re all interconnected and rooted in the same source, like the many heads on the Hydra. Although they can’t be separated from each other, the privileging forces affect people in different ways, so it’s still meaningful to talk about them as separate issues.

My Beautiful Laundrette is an interesting film, which ends up feeling more like you’re watching a short section of someone’s life unfold instead of a movie. “The movie is not concerned with plot, but with giving us a feeling for the society its characters inhabit. Modern Britain is a study in contrasts, between rich and poor, between upper and lower classes, between native British and the various immigrant groups‒ some of which, such as the Pakistanis, have started to prosper. To this mixture, the movie adds the conflict between straight and gay.” (Ebert) The contrasts in the movie make it interesting to look at through the perspective of the Hydra, with every character being marginalized but also benefiting from a privileging force in some way. There’s a lot going on in the film which isn’t relevant to hetero/cisnormativity, so I highly recommend watching it to get a better feel for how many other heads of the Hydra it depicts and their intersectionality.

Honestly, cisnormativity isn’t very present in the film, at least not in a way that’s meaningful to discuss. There’s a lack of transgender representation, but that means there isn’t anything to talk about in relation to its depiction of cissexism, besides the fact that you are meant to assume all the characters are cis. There’s a one-off comment about Omar’s penis by his father, and then nothing else. However, heteronormativity is much more visible.

The entire first third or so of the movie, there are a few hints towards Omar’s non-heterosexuality, but mostly we see characters unquestioningly uphold heteronormativity. Near the beginning, Omar’s father remarks to his brother Nasser over the phone that he should see about finding Omar a wife while getting him a job, implying he’s about the age where it’s expected, but hasn’t taken any significant interest in women. Later, when Omar visits Nasser’s house, he reconnects with his cousin Tania and she makes sexual/romantic advances to him, which he isn’t unreceptive to. There are also points where Nasser and Tania herself suggest her as a marriage prospect for Omar. Even Omar’s relationship with his poor white partner who rekindles a romance with him, Johnny, just comes across as reconnecting friends at first. Then, about 44 minutes into the film, it’s made clear that Omar and Johnny are involved with each other when they kiss in an alley.

Tania, Omar, and Johnny are all part of a younger generation, and they approach heterosexuality with a more casual attitude compared to the older characters. Omar and Tania casually get engaged or at least say they’ll get married a few times in the film, but it’s also made pretty clear to the viewer that Omar is with Johnny and Tania wants to move out and live away from home. Both Omar and Johnny kiss Tania at a point in the film, and there’s a moment where Tania is vaguely possessive over Omar, but none of these moments are played with any lasting seriousness. In fact, the possessive scene with Tania came across as humorous to me because it’s quite literally the only time any character clocks them as not-straight and it happens a few minutes before their kiss confirms the relationship. She realizes it because of one small, intimate (though still platonic) moment, but when Omar’s uncle walks in on them half-naked later in the film, he doesn’t even seem very suspicious.

All other characters in the film, including the older upper-class Pakistani characters and Johnny’s old white fascist gang, seem to have no clue they’re anything but heterosexual. This implies that the more conservative-minded people probably aren’t even used to considering options besides heterosexuality, or at least that the people around Johnny and Omar hold such rigid views of them that they can’t fit them not being straight into that view. Both their main social groups are marginalized in a way, but also benefit from a privileging force, and so heteronormativity is assumed so intensely that they barely have to hide their relationship. The fact that they do hide it anyway just means we know there would be consequences if they’re found out.

“Joker” (Classism)

By Harish Prasad

All the heads of the Hydra show the types of privilege that exist around the world, with each head representing a different one. The head of the Hydra this post is about is class privilege/classism. It represents the conflict between upper and lower classes, and people of higher classes would be the privileged group. An example, outside of the 1% in the US, would be the caste system in India. At the top are Brahmins, and at the bottom are the Untouchables, and most people who aren’t Brahmins are looked down upon. This post is focusing on the movie Joker, which depicts this conflict between upper and lower classes well. This movie could also depict the ableism head of the Hydra, since this is a movie about a mentally ill man who is mistreated.

Joker is an origin story that centers around the Joker, Arthur Fleck, a man with a severe mental illness who lives in poverty in a beaten down apartment. The way society treats him drives him into madness which ultimately ends in him donning his villainous alter ego as the Joker. Arthur is clearly alienated from people, even other poor people, and thought of as a “freak” to the point where he gets fired from his job at a clown agency. This had been the case his whole life, as he lacked a social group, or a group that “consists of two or more people who regularly interact on the basis of mutual expectations and who share a common identity.” (S: UCSW, 6.1) This movie also has messages about capitalism. It can be seen as a critique of capitalism in multiple ways, but one good example in the movie is when Arthur can no longer get his medications or see his social worker anymore because they cut funding and shut down the place he goes to.

There will be a few scenes that piece together the story and how this movie ties into the classism head of the Hydra. The first scene is a scene on the subway where three well-dressed guys, presumably more upper-class, harass and assault Arthur because of his brain condition that makes him unable to control his laughter at times. Arthur has a gun on him and kills them, which leads to something like a social movement where lower-class people start protesting Thomas Wayne and other rich people in Gotham.

This leads into the next scene, where Thomas Wayne talks about the murders on TV and says a couple of things that drive the point. He stands up for the men who were murdered, who were apparently Wayne Enterprises employees, and talks about what good people they were. He also talks down to the protesters for taking the side of the killer and says the murderer was clearly envious of people better off than him. At the end of the interview, Wayne says that until poor people change for the better, “those of us who made something of our lives, we’ll always look at those who haven’t as nothing but clowns.” He also says people need to realize that he’s their only hope, which is why he’s running for mayor.

This leads into the last scene, which is the climax near the end of the movie, after Arthur fully transforms into the Joker. When he is on the Murray Franklin show, the Joker reveals that he’s the one who killed the men on the subway. He says that he didn’t kill them to start a movement; he did it because they are awful, and people are awful. He says this because almost everyone in his life mistreated him, and the system (which he criticized) left people like him to fend for themselves with no help. The most important part of this scene is when he rolls his eyes and asks “Why is everyone so upset about these guys? If it was me dying on the sidewalk, you’d walk right over me. I pass you every day on the sidewalks and you don’t notice me. And what, everyone cares about these three guys because Thomas Wayne cried about them on TV?” Thomas Wayne being a rich guy drew all the attention to these guys, but Arthur says if the murder happened to “anyone like him” (poor and mentally ill), nobody would bat an eye, which has a lot of truth, based on the events of his tragic life. He then asks if Thomas Wayne had ever imagined what it was like to be someone like him, and says Wayne thinks that “we’ll sit here, and take it like good little boys,” which seemingly is the mindset of the rich in Gotham. These were the most impactful examples of how this head of the Hydra is tackled in this film (with definitely more in there).

“Forrest Gump” (Ableism)

By Hannah Ellowitz

The Hydra metaphor proves that in order to fight for “all humanity,” we must attack many individual yet interconnected systems from the root (or body of the creature) in order to break down the systems that favor certain types of people. The privileging force of ableism is a newer addition to the Hydra, and the term is defined by The Center of Disability Rights, Inc. as “a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other.” (CDR)Leah Smith, a writer, communications professional, and disability advocate says that “Ableism is intertwined in our culture, due to many limiting beliefs about what disability does or does not mean, how able-bodied people learn to treat people with disabilities and how we are often not included at the table for key decisions.”

In July 2016, the Ruderman Family Foundation released their White Paper “On Employment of Actors With Disabilities in Television”, sharing that “95% of characters with disabilities on television were played by able-bodied actors.” (RFF)Furthermore, if the current Academy Awards trend continues as is, any actor nominated for their portrayal of a disabled/non-neurotypical role has a 50 percent chance of winning that prestigious award. Most notable examples include Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man, Eddie Redmayne in The Theory of Everything, and Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump. In the Oscar’s nearly 93 year history, only 2 disabled actors have received awards for their work; Harold Russel was a handless non-professional actor who won Best Supporting Actor in 1946 for his role in The Best Years of Our Lives, and deaf actress Marlee Matlin won Best Actress in 1986 for her portrayal of Sarah Norman in Children of a Lesser God. I’m curious as to what abled viewers are so fascinated by when it comes to disabled persons in film, and how close these portrayals by able-bodied and neurotypical actors are to the lived experiences of disabled people. I decided to watch Forrest Gump through a more specific lens to help me better understand ableism and its Hydra head.

Forrest Gump is iconic for its humor, charm, and heartbreak. The notoriety surrounding the story’s many disabled characters brought newfound attention to the disabled community through film. The story was written, developed, and performed entirely by neurotypical, able-bodied people. I don’t at all believe that the Forrest Gump story is primarily about disability, but it is a central part of multiple main characters’ livelihood, making disability a relevant piece of the story. The Amazon Prime blurb about the film describes Forrest as being slow-witted, but it’s hinted throughout the film that he is disabled, despite the many wild experiences and accomplishments he achieves throughout his lifetime. The only disability that is specified in the script is that Forrest’s IQ is 75. The lack of specification with Forrest’s disabilities leaves audiences to stereotype his conglomeration of malfunctions into something misinformed and ableist.

The beginning of the film features a young, severely weak, and crippled Forrest running so fast that he breaks his leg braces and escapes his bullies, finally free from being physically disabled. After breaking through these physical barriers, he eventually gets accepted to a top university with a football scholarship, so “thankfully” he wouldn’t need the intellectual factor to influence an acceptance. From early on, we’re shown that for a disabled person to become successful, they must rid themselves of their hindrance and become abled in a way they naturally aren’t. There’s an excellent review question at the end of Chapter 4 in our text that definitely made me question my perspective on what it means to be equal in the case of ability. “Do you agree that effective socialization is necessary for an individual to be fully human? Could this assumption imply that children with severe developmental disabilities, who cannot undergo effective socialization, are not fully human?” (S:UCSW, 4.1) Socialization is, in a way, what shapes a person into a kind of individual, but what about those who can’t socialize? Forrest is incredibly social despite his disability, but how would audiences have viewed an antisocial achiever? Would it have made it as exciting of a movie?

Much of what I read by disabled bloggers and writers spoke to the character Lieutenant Dan and how they felt connected to him in more ways than they had with Forrest. Dan is presented to us as a dashing, masculine hero who Forrest is afraid to disappoint, only to have his heroism stripped when he becomes an amputee in Vietnam. The script does an okay job with allowing Dan to express his anger however he chooses, allowing him to speak directly to the overwhelmingly angry feelings experienced by many disabled viewers. Over time, Dan and Forrest develop a sort of Of Mice and Men dynamic, and they connect during the moment when they bring two sex workers back to their apartment after a night of drinking. After Forrest makes it clear he doesn’t have any interest in the women, Dan falls out of his wheelchair in protest, leading to the women snickering and insulting them as they leave. Here, the audience is reminded what it means to be diminished to being “crippled” or an “idiot”. I think that scene brings audiences into a vulnerable moment for these characters and shows how painful it can be for disabled people to be othered. Eventually, however, Dan is “redeemed” through the gift of prosthetic legs, meaning he’s now successful at acting like an abled person, free from his disability.

I don’t think there was any agenda by the creatives of the film to make a strong statement about disabled people– but I’d say there is a subtle commentary on the traumatic aftermath of Vietnam veterans who’ve developed disabilities and PTSD after their time overseas. I think there should have been more awareness and inclusion of disabled actors or creators through the development of the film, in an effort to make the story a bit more truthful to real experiences, despite the story itself being a bit satirical and humorous. Looking at this now, almost 30 years later, it seems rather bold for able-bodied and neurotypical people to produce a movie like Forrest Gump. It does seem as though folks in disabled communities resonated more with parts of this story and the effect it shows of society’s othering through ableism. As we strive for a more inclusive community, I think it’s most important for storytellers and creatives to consider how those receiving the stories feel about their portrayal and how the effects of viewing can help others better understand new perspectives of the human experience.

I’ll end with a section of an article by Kristen Lopez on her connection to Lieutenant Dan in Forrest Gump:

“And yet for all the ways Lieutenant Dan is indicative of the lack of change in representation, he’ll always be my first; the first time I saw someone in a wheelchair who said a lot of the things I was feeling internally regarding my disability. Outside of the story, it was amazing just to see a wheelchair on-screen. Sure, Dan uses a standard hospital wheelchair that would provide no comfort or support for his body, let alone be difficult to wheel full-time. (No wonder he fell down ramps and almost got hit by cars!) It was obvious no one was actually disabled on the writing team, but for a child who’d only been using a wheelchair for a few years, something was better than nothing.” (K. Lopez, Forbes)

“Up” (Ageism)

By Olivia Pierce

Tom Arcaro uses the Hydra as a metaphor to depict and frame the norms related to the privileging/oppressive forces that are fueled by “othering,” the justification of one group dominating another. One of the privileging forces in Arcaro’s Hydra model is ageism or discriminating against someone because of their age. Ageism assumes that the very old or the very young are biologically or culturally inferior to others. It’s related to ableism, which assumes that non-abled people are inferior. Since the very old and very young are generally assumed to be not as capable as an adult, they’re linked. Ideas about their inferiority are used to justify unequal treatment of people in these groups.

The movie Up highlights ageism as it relates to an elderly man, Carl Fredricksen. At the beginning of the movie, Carl is depicted as a stubborn, grumpy old man who is resistant to change and wants to be left alone. He uses a walker, has hearing aids, and wears dentures. We see examples of ageism throughout the movie, including the Wilderness Explorers’s assumption that older people need assistance and have a requirement to earn a merit badge for “Assisting the Elderly.” Carl is also shown as out of touch with what’s going on in the world (not knowing what a GPS is), and he’s described as smelling like “prunes and denture cream.” Each of the examples illustrate different dimensions of aging, as described by gerontologists: chronological, as Carl is 78 years old; biological, with his bad back, hearing impairment, dentures;psychological, by being stubborn and grumpy after losing his wife; and social, how he’s seen by others. (S:UCSW, 12.1)More strictly speaking, social aging refers to the “changes in people’s roles and relationships in a society as they age.” (S:UCSW, 12.3)

The movie may have helped people think about their views on aging, at least temporarily. It brought out the ageism in reviewers and toy manufacturers. They had negative views about its success because “the main character, a grumpy old man, is not considered commercially attractive.” (Walker) These people were essentially saying the movie did not have value because they could not profit off an elderly character.

Two studies, conducted by Humana and USC Annenberg, assessed the portrayal of older people in film and found that “few characters aged 60 and over are represented in film, and that prominent senior characters face demeaning or ageist references.” They also found that those depictions were not realistic. “Our popular cultural narratives do not present the stories and experiences of seniors. As a result, viewers miss out on rich depictions that can confront our stereotypes about older individuals and broaden our views about what it means to age today.” (Smith et al.)

It is interesting to note that in Up, Carl changes from a grumpy, stubborn man to a hero. He defies his age, fighting off the villain (although the movie sticks with elderly stereotypes by having his back go out and his dentures fall out), and ending with a new outlook on life. His determination flies in the face of ageism. It’s too bad that there aren’t more older characters in children’s movies. It would be a great place to start for changing people’s views on age.

“Okja” (Anthropocentrism)

By William Thomas

All the heads of the Hydra can represent forces which derive from “othering” and are embedded into our culture. Each head has its own oppressive force for each way to differentiate a person from another group. The Hydra is one creature just as each head of discrimination has an interconnected relationship with the others.

Anthropocentrism is the mindset that humans are at the center of the world. This view that humans are the most important form of life appears in many aspects throughout our history and particularly Western culture. The most common example of anthropocentrism is animals vs. humans. Many would argue that a human would not be classified as an animal because of our heightened awareness and consciousness compared to the other species. However, humans are still driven by biological desires and our animal nature could be one of the driving forces of deviancy. We are creatures affected by many things, but we are also still animals and driven by biological forces. The practice of sociology argues that culture has a deeper influence on human behavior compared to biology. (S:UCSW, 3.1) This may be true, but biological forces are the initial arbiter of our actions, and our cultural influences filter out decisions that may be considered deviant.

Along with the other heads of the Hydra, anthropocentrism spreads the idea that one individual or group is superior to another. This view of the world spreads the idea to other cases. The validation of anthropocentrism validates the thought that other heads of the Hydra are acceptable ideals. The symbolism of the Hydra helps one understand that the forces of “otherism” are one and the same: different minds but one body.

Humans generally don’t give too much attention to the suffering of animals, whether it’s human-caused or some other preventable occurrence. We are willing to sacrifice animals for the greater good of humanity or individual, even if it means killing a few elephants for a nice set of piano keys. This draws back into our talks about capitalism and how people don’t care about the suffering they create if they can make a sweet profit off it. It is a common belief that animals serve human existence by providing us food and otherwise have no other purpose in “our” world. We lock them away in zoos for our entertainment and eat them for our pleasure. The treatment of animals and their habitats has caused numerous extinctions, as well as created many endangered species. The excuses for the treatment of animals can be related to the same excuses made to justify colonialism: “We are superior and know what this group needs better than they do.” This excuse implies that humanity is some divine creature that was specifically made to control nature.

“On the Basis of Sex” (Patriarchy)

By Caroline Borio

The Hydra is a metaphor that represents the privileging forces that exist throughout the world, and more importantly, how they all interact. All heads share a common body, acknowledging that they all stem from the same source and they are all connected. One of the heads is the patriarchy, which Merriam Webster first defines as “social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family, the legal dependence of wives and children, and the reckoning of descent and inheritance in the male line.” However, I prefer their second definition, which defines patriarchy as “control by men of a disproportionately large share of power.” (“Patriarchy.”) The patriarchy stems from sexism, which has led to the construction of gender roles and stereotypes about women and has prevented them from having the same rights as men throughout history. Women have had to fight for the right to vote, to work the same jobs as men, and so on. Even today, it’s unconsciously presumed that a woman’s job is to stay home and take care of the children while men go out and work. This is ever-present in our society, undeniably in the workplace, and there’s a direct connection between this stereotype and the film On the Basis of Sex.

On the Basis of Sex explores the ideas of the patriarchy and gender inequality as it follows the early life of Ruth Bader Ginsberg. However, before the film gets to the main plot, it shows how significant gender inequality was in Ginsberg’s personal life. In one of the very first scenes, Ginsberg walks into Harvard Law School surrounded by only men, all carrying briefcases and wearing matching suits. At the first dinner with the Dean of Harvard Law, he asks the women why they’re at Harvard and “occupying a place that could have gone to a man.” Finally, even after attending Harvard and Columbia, and graduating top of her class, Ginsberg is unable to get a job at a law firm, and instead takes a job as a law professor. Later in life, Justice Ginsberg said this about the experience: “I was Jewish, a woman, and a mother. The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible.” (Thulin) Even this early on, the movie demonstrates how sexist stereotypes and gender roles are present in our society and institutions. These assumptions can become incredibly harmful as they form a system of oppression that says women are less than men. That said, Ginsberg is an example of a woman who challenged the patriarchy by pursuing a career that is not traditionally a woman’s “job,” and used her career to challenge laws that differentiated based on sex.

The movie focuses on Ginsberg’s first case, where a man named Charles Moritz was denied a tax deduction on caregiving expenses for his ill mother, even though this deduction was given to other people in his position. The law said the deduction was to be given to “a woman, a widower or divorce, or a husband whose wife is incapacitated or institutionalized,” and Moritz was a single man who had never been married. (US Court) Ginsberg argued that this was discrimination based on sex, because women in the same circumstances would be given the tax deduction. Ginsberg believed this perpetuated the idea that women should be responsible for arranging caregiving, even though there is no reason a woman should be providing care more than a man. On its own, this case was important, but it was also the first step towards a larger goal. At the time, there were 174 laws that differentiated based on sex, and winning this case was Ginsberg’s first step to taking down all laws that assume gender inequality. In her final statement in court in the movie, Ginsberg says, “Our sons and daughters are barred by law from opportunities based on assumptions about their abilities. How will they ever disprove these assumptions if laws like Section 214 are allowed to stand?” This assumption about abilities based on sex is at the foundation of the patriarchy, and creates gender inequality in our institutions, laws, and everyday life.

While On the Basis of Sex focuses primarily on sexism, relating it back to the Hydra, it’s important to remember that this is just one of many privileging forces that is based on the “othering” of a particular group. People of various races, gender identities, abilities, and more face similar situations in which they are “othered.” While it may be impossible to kill the Hydra entirely, films like On the Basis of Sex remind us that it is critical to engage in an attempt of taming the Hydra to create a more equal, just world for everyone.

The Hydra in Film References

“On the Basis of Sex”

“Patriarchy.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/patriarchy. Accessed 16 Jun. 2021.

Thulin, Lila. “The True Story of the Case Ruth Bader Ginsburg Argues in ‘On the Basis of Sex.’” Smithsonian Magazine, 24 December 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-case-center-basis-sex-180971110/. Accessed 17 June 2021.

US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit – 469 F.2d 466 (10th Cir. 1972). Moritz v Commissioner. Justia US Law. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/469/466/79852/. Accessed 17 Jun. 2021.

“Race/Ethnicity”

“Humanitarian.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/humanitarian. Accessed 17 Jun. 2021.

“Colonialism/Paternalism in Victoria and Abdul”

“Colonialism Noun – Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes: Oxford Advanced American Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com.” Colonialism Noun – Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced American Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com, 2021, http://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/colonialism.

“Paternalism.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/paternalism. Accessed 17 Jun. 2021.

“What Countries Were in the British Empire?” Schoolshistory.org.uk, Schoolshistory.org.uk, 2021, http://schoolshistory.org.uk/topics/british-empire/questions-about-the-british-empire/what-countries-were-in-the-british-empire/.

“Hetero/Cisnormativity & My Beautiful Laundrette”

Ebert, Roger. “My Beautiful Laundrette Movie Review (1986): Roger Ebert.” Movie Review (1986) | Roger Ebert, Tim Bevan, 11 Apr. 1986, www.rogerebert.com/reviews/my-beautiful-laundrette-1986.

“Joker and Classism”

“‘Joker’ and the Crisis of Capitalism.” New Politics, 24 Nov. 2019, https://newpol.org/joker-and-the-crisis-of-capitalism/.

Robinson, Chauncey K. “‘Joker’ Exposes the Broken Class System That Creates Its Own Monsters.” People’s World, 4 Oct. 2019, https://peoplesworld.org/article/joker-exposes-the-broken-class-system-that-creates-its-own-monsters/.

Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, 6.1, 13.2

“Ableism”

Smith, Leah. “Center for Disability Rights Inc.” #Ableism – Center for Disability Rights, www.cdrnys.org/blog/uncategorized/ableism/.

Woodburn, Danny, and Kristina Kopić. “ON EMPLOYMENT OF ACTORS WITH DISABILITIES IN TELEVISION.” THE RUDERMAN WHITE PAPER, Ruderman Family Foundation, July 2016.

Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, 4.1

Lopez, Kristen. “’Forrest Gump’ at 25: Disability Representation (For Better and Worse).” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 5 July 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/kristenlopez/2019/07/05/forrest-gump-at-25-disability-representation-for-better-and-worse/?sh=81a3b00664d5.

“Ageism and Up”

Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, 12.1, 12.3

Smith, Dr. Stacy L., Pieper, Dr. Katherine, and Marc Choueiti. “USC Annenberg Film Study: Pop Culture Stereotypes Aging Americans.” Edited by Dr. Stacey L. Smith, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, 12 Sept. 2016, http://annenberg.usc.edu/news/faculty-research/usc-annenberg-film-study-pop-culture-stereotypes-aging-americans.

Walker, Kim. “New Disney Movie Sparks Ageism Debate.” Silver Group, 29 Apr. 2009, http://www.silvergroup.asia/2009/04/29/new-disney-movie-sparks-ageism-debate/#:~:text=New%20Disney%20movie%20sparks%20ageism%20debate%20Apr%2029%2C,grumpy%20old%20man%2C%20is%20not%20considered%20commercially%20attractive.

“Anthropocentrism and the Meat Industry”

Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, 3.1

Tom Arcaro is a professor of sociology at Elon University. He has been researching and studying the humanitarian aid and development ecosystem for nearly two decades and in 2016 published 'Aid Worker Voices'. He recently published his second and third books related to the humanitarians sector with 'Confronting Toxic Othering' published in 2021 and 'Dispatches from the Margins of the Humanitarian Sector' in 2022. A revised second edition of 'Confronting Toxic Othering' is now available from Kendall Hunt Publishers

More Posts - Website

Follow Me:

elites are privileged not only due to their wealth but also their membership in different dominant groups such as ruling parties, majority ethnic groups, affiliations with dynastic political and business families, roles in public administration, and other politico-economic associations. They often misuse their political power and commit nepotism in order to seize social resources; on the other hand, people at the bottom of the power hierarchy accept these imbalances as foregone.

elites are privileged not only due to their wealth but also their membership in different dominant groups such as ruling parties, majority ethnic groups, affiliations with dynastic political and business families, roles in public administration, and other politico-economic associations. They often misuse their political power and commit nepotism in order to seize social resources; on the other hand, people at the bottom of the power hierarchy accept these imbalances as foregone. underlying politico-cultural pathologies are identical. Both countries were colonized by the British Indian Empire, which cultivated toxic othering between communities through divide and rule policies, which systematically broke up larger concentrations of power into pieces that individually had less power than the implementer of the strategy, enabling the empire to secure its dominion (Christopher, 1988).

underlying politico-cultural pathologies are identical. Both countries were colonized by the British Indian Empire, which cultivated toxic othering between communities through divide and rule policies, which systematically broke up larger concentrations of power into pieces that individually had less power than the implementer of the strategy, enabling the empire to secure its dominion (Christopher, 1988).

Follow

Follow