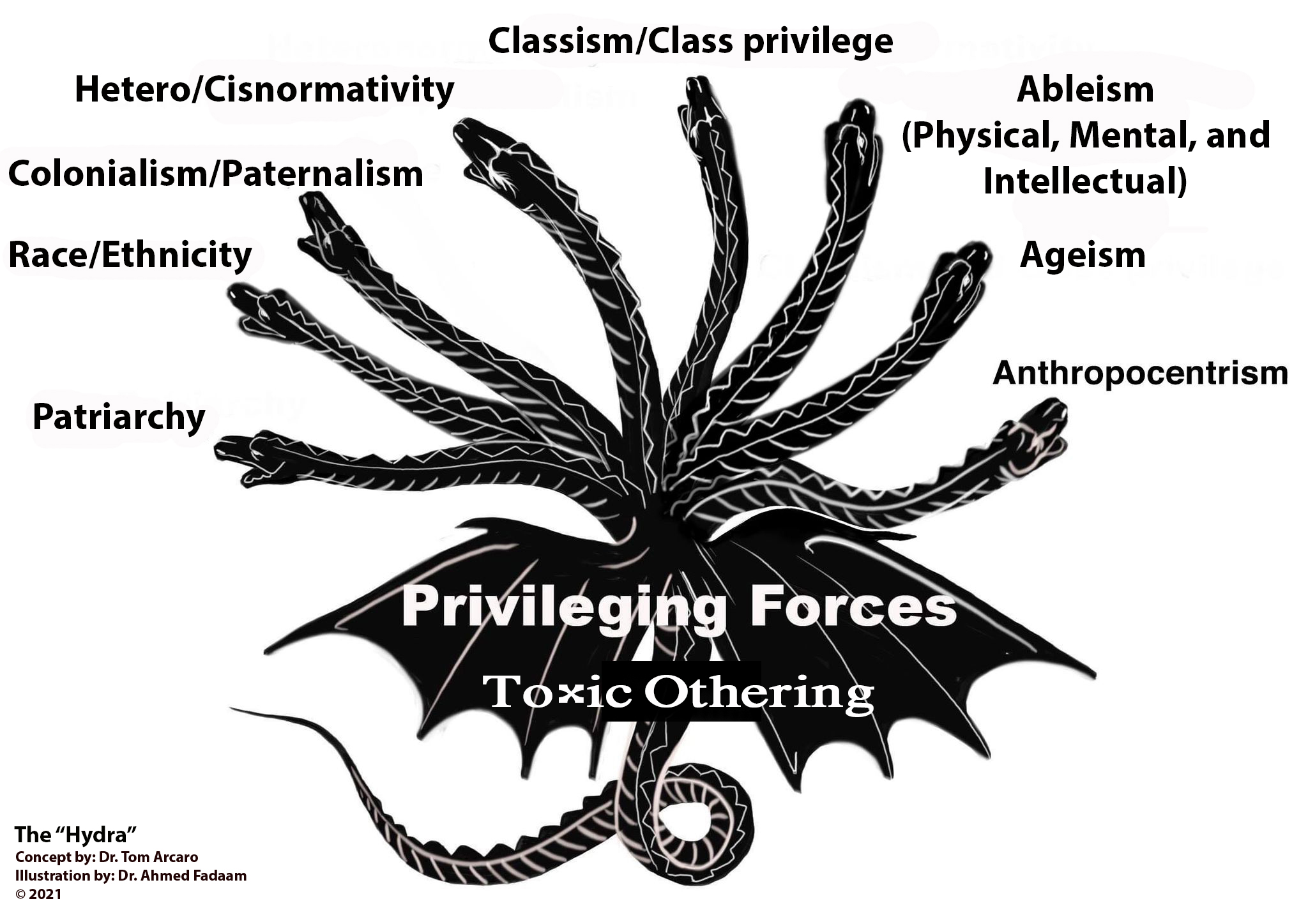

Advanced Hydra Theory: Understanding power and social forces

[Updated 6 August]

Thank you to my learners for asking amazingly insightful questions

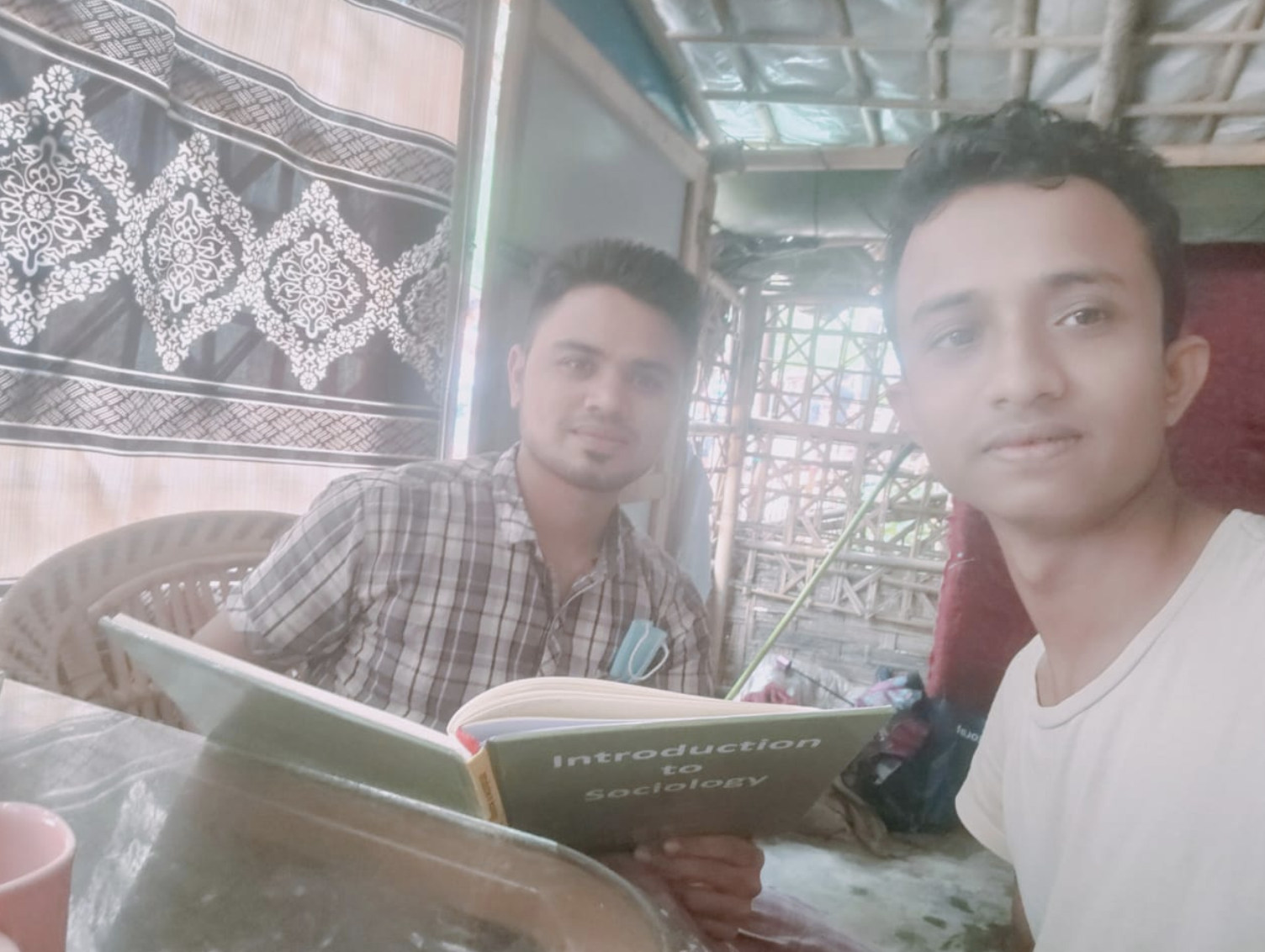

I am covering the chapter on social stratification with my Rohingya and Bangladeshi learners just now, and I want to thank them as a group and especially our translator/teaching assistant Azizul Hoque from the Centre for Peace and Justice, Brac University for continuously inspiring my

teaching and for providing excellent questions.

This discussion of stratification cuts to the heart of Hydra theory and its emphasis on privileging forces, and by probing deeply we can advance our understanding.

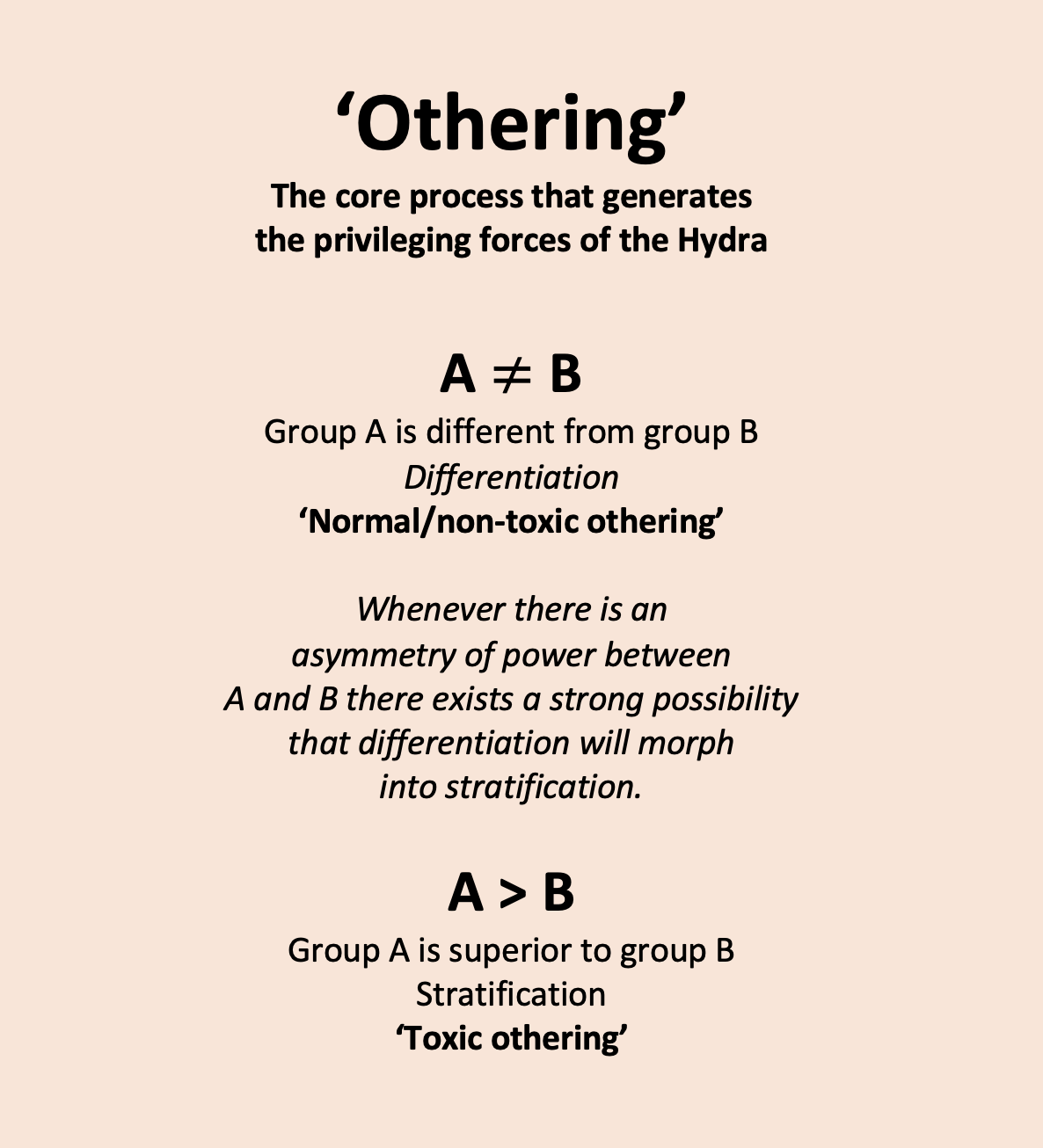

For decades in my intro to sociology classes I have summarized my longer and more technical definition of social stratification into just three words: structured social inequality. As I grappled with how to explain the phenomena of social stratification I was forced to get to the fundamental nature of social inequality, that is, to get at the root of the issue, to get radical. Reflecting on our class’ earlier conversations about othering and toxic othering, we were all forced to probe into a sober reality. Whenever there is an asymmetry of power in any social situation social differentiation can (must?) transition into stratification. This forces us to probe even deeper and thus deal with the concept of power. I explained to them that social powers are at play constantly and a good sociologist studies these social forces at both the micro (interpersonal) and the macro (community, organizations, and states) levels.

Here are the questions I posed in a short video message to my class … and to myself as I continue exploring the concept of critical Hydra theory.

“As we discuss social stratification it is necessary for us to grapple with the concept of power. Power has been studied through time by all major sociologists, most particularly Max Weber who defined power as the ability to impose ones will over other people. And so as we think about power I want you to consider power in your life.

Who has power to make decisions that affect you: in your family, in your ‘village’, in your section of the camp, in the camp overall, in Bangladesh, in the Southeast Asian region, and globally? And considering each of these levels: Where did their power come from? How do those in control demonstrate their power (enforce their will)? What are the consequences when you or another person challenges their power? In your opinion do those in power at all of these levels -the family, village, in the [refugee] camp, in Bangladesh, in Southeast Asia, and globally- do those in power act fairly? What are the consequences for you or others for ‘speaking truth to power’ that is confronting people when they are using their power incorrectly or in an unjust way? Another question to ask is how is their power used to support a concept we talked about in depth, ‘toxic othering’?

What personal power do you have and how do you use it in your life? How do you use your power(s) to make your life better? How do you use your power(s) to make your family’s life better? How do you use your power(s) to make your community’s life better? How do you use your power(s) to make your village better? How do you use your power(s) to make Bangladesh or Myanmar better? How do you use your power(s) to make the world better?

Those are all very important questions that I just asked and I don’t expect everyone to answer them all, but I do want you to think about those questions, think about power swirling around you as you walk through the village, as you walk through the camp. Who has the power to control, who has the power to say what happens and what does not happen, and how did they get that power.”

In response to the video concerning power my teaching associate Azizul Hoque received a reflection from a Bangladeshi learner while he was mentoring the cohort. The learner noted,

“People with money and political affiliation are seemed to be considered as power holder regardless of his personality, education or capacity to guide community properly. Poor villagers unquestionably accept the words and work of a local influential person as a guaranteed as they can offer money to solve a social problem”.

Azizul replied to the learner and observed,

“In an underprivileged area like Cox’s Bazar most people are politically unaware of where power lies, especially at higher levels. The inequality conversely paves the way for certain tiny classes such as rich peasants, the family whose sons or relatives are government officials, the local political cadre who receive government’s contracts for infrastructural development or relief distribution, these people are small in number and common people cannot deny their influence. It motivates the young of these families, who are outside the power block, to work for a wage or migrate to Middle Eastern countries as labour. It emancipates some of them from poverty however the majority can hardly come out of this powerless cycle. Certain cultural bottlenecks exist such as malpractice of bureaucratic power, nepotism in resource distribution and petty corruption. Therefore power is unequally distributed in the communities where money and muscles act as determinates and whereas the socio-economically impoverished/marginalized species of the community are seemed to be taken it guaranteed.

The power dynamics of a refugee community are very different from host communities.”

The list of power influences that Azizul notes is indeed a massive problem. Massive understatement: The corrupt actions of those who gain power leads to much social injustice and systemic marginalization, and understanding full nature of the power dynamics of one’s social position is frequently difficult if not at times impossible. This is in part because legitimate and illegitimate power sources can exist separately but also within the same organizational entity, for example a corrupt official within a legitimate organization.

One of my refugee learners asked,

“When an authority people say criminal to an innocent public as accusation, it is ok. When a civilian says ill about authority, it is crime.”

He went on to give many other examples, each with the same theme, finally asking “What’s sociological views on this?” Here is the gist of my response.

“These are all excellent questions and each one points to the question of power and how it is used. One social philosopher put it this way, “The ruling ideas of any age are ever the ideas of the ruling class.” That is to say, those in power get to make the rules, and they sometimes (maybe frequently) make rules that justify their own power and also justify rules, norms, policies and laws that serve to marginalize other groups (that is, they use their power to engage in toxic othering).

The role of the sociologist is to objectively, systematically, and thoroughly describe, document, and analyze power: how it is gained, maintained, used, and abused. Using this information the sociologist supports those who would challenge those in power when they are using their powers in harmful ways. Indeed, the reason d’être of sociology is to ‘investigate humanity for the purpose of service.’

There are several aphorisms (sayings) that come to mind when talking about power. Perhaps the most often quoted is that “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” This 1887 statement by the British historian and moralist Lord Acton argues that as individuals gain power their sense of morality diminishes.

And this is how toxic othering leads to the marginalization of some lesser privileged groups: those in power, increasingly intoxicated by this power use their advantage to play on the insecurities of those ‘beneath’ them, making them feel inferior, thus setting in place a structure of power relationships that, over time, ossifies into permanence, becoming ‘baked into’ the culture. This process is at the origin of and indeed what fuels the body of the Hydra.

Yet another Brit, novelist and social critic George Orwell makes much of the concept of power in two of his most influential works, 1984 and Animal Farm. In the later book, the idea that ‘power corrupts’ is indeed the main message is illustrated in the book by a pig named not coindidentially, Napoleon. The pigs, now in control of the farm and needing to explain why they have more power than the other animals state that ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.’ With this wording magic the transition from merely different (A≠ B) to being superior (A > B) now complete.

Another frequently mentioned quotation (though it may now have aged out of common usage) is “Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac.” This statement is thought to be first uttered by the Frenchman Napoleon Bonaparte but it

gained much currency in the US in the late 1900’s by American diplomate Henry Kissinger. Though the truth of this statement is suspect, the fact that men believe it to be true may help explain why some men seek power.”

This last aphorism leads me to put weight on the conjecture that out of all the privileging forces, that of patriarchy (sexism) was the first to emerge and take root. In our species males wield physical power over women, and this asymmetry of power eventually was exploited in culture after culture. There is much written about the origin of patriarchy, some of it controversial, but that it exists now and is inextricably woven into the fabric of most existing cultures is a fact we cannot avoid.

One premise of my thinking is that allowing for and justifying one form of structured social inequality provides normative support for the marginalization of some humans by others in their culture thus making it easier and perhaps inevitable that additional social status power differences to be normalized. Restated, can it be argued, for example, that gender differentiation will lead to gender stratification and normalization of this social relationship gives license to additional toxic othering based on various status differences? I think yes.

Some basic sociology

One of our classmates asked this question,

“Although social stratification is assumed as a system of inequality, why does everything [in] society support this system?”

My explanation to him was that yes, social stratification based on differences in status exists in virtually every culture, both past and present. But why? What is the social function of inequality? If social stratification is a cultural universal (true at least in the last several thousand years) why is this so? Other cultural universals like the family, religion, or art can be explained by how they function to maintain a culture’s integrity, and perhaps this is so for structured social inequality.

The functionalists logic goes like this. Using the organic analogy, there are no superfluous organs in the body; all the parts of the body’s system are interdependent with all the other parts; every part of the body is there for a reason, and all of the systems have a mutual goal, that is to keep the body functioning in a healthy fashion. The same is so in cultures. Cultures are integrated wholes where all the parts (i.e., social institutions like the family) are mutually interdependent and all geared to keep the culture running optimally.

So, is structured social inequality -a cultural universal- healthy for society?

The answer to this question is not simple, but the critical theoretical tension here is between the two main macro theories in sociology, namely functionalism and conflict theory. In question is whether or not social inequality, the unequal distribution of status and power, is or is not necessary and inevitable for cultures to function. The debate in sociology is more narrowly around the question of class, caste, and the distribution of economic power, but I argue that the underlying logic works for other privileging forces as well.

American sociologist Kingsley Davis summed up the functionalist perspective in one sentence:

“Social inequality is thus an unconsciously evolved device by which societies insure that the most important positions are conscientiously filled by the most qualified persons.”

Structured social inequality is necessary and inevitable, according to the functionalism perspective. In any culture there is a complex division of labor needed to get all necessary tasks accomplished and keep the culture running. Some jobs are more important than others and these jobs must be rewarded more highly in order to attract the most qualified individuals to do the job. Some people must be able to acquire more power and privilege than others to encourage them to take on the more critical tasks. Social inequality must be part of the structure of an optimally functioning culture, so says the functionalist.

The conflict perspective, implicitly adopted throughout my posts on the Hydra and in my discussions of toxic othering, is that social inequality is neither necessary nor inevitable to for a culture to function, and that a world without extreme social stratification can be made possible by human efforts to put in place norms, policies, and laws which embrace differentiation but reject toxic stratification. It is possible for humans to live an essentially egalitarian world where there may be some meaningful yet moderate disparities of material wealth but all members of the culture have access to basic needs and pathways to dignity.

Ultimately Critical Hydra theory is an effort to reach what I define as the goal of humanitarianism: an ideology of human growth and potential based on the assumption that we should all be working toward a world where every human not only has pathways to but is actively encouraged to reach all their potentials, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. And further that these pathways acknowledge and respect the rights and needs of not only future human generations but other life forms as well.

The sociological debate historically has centered around social class differences, but the Hydra theory proposes synchronous and inherently intersectional othering processes related to gender, ethnicity, etc. and this toxic othering (the transition from differentiation to stratification) slowly and insidiously being normalized for all the heads of the Hydra. This quote from the original source of most conflict theory, Karl Marx, offers this summary explanation,

“The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.”

Social forces

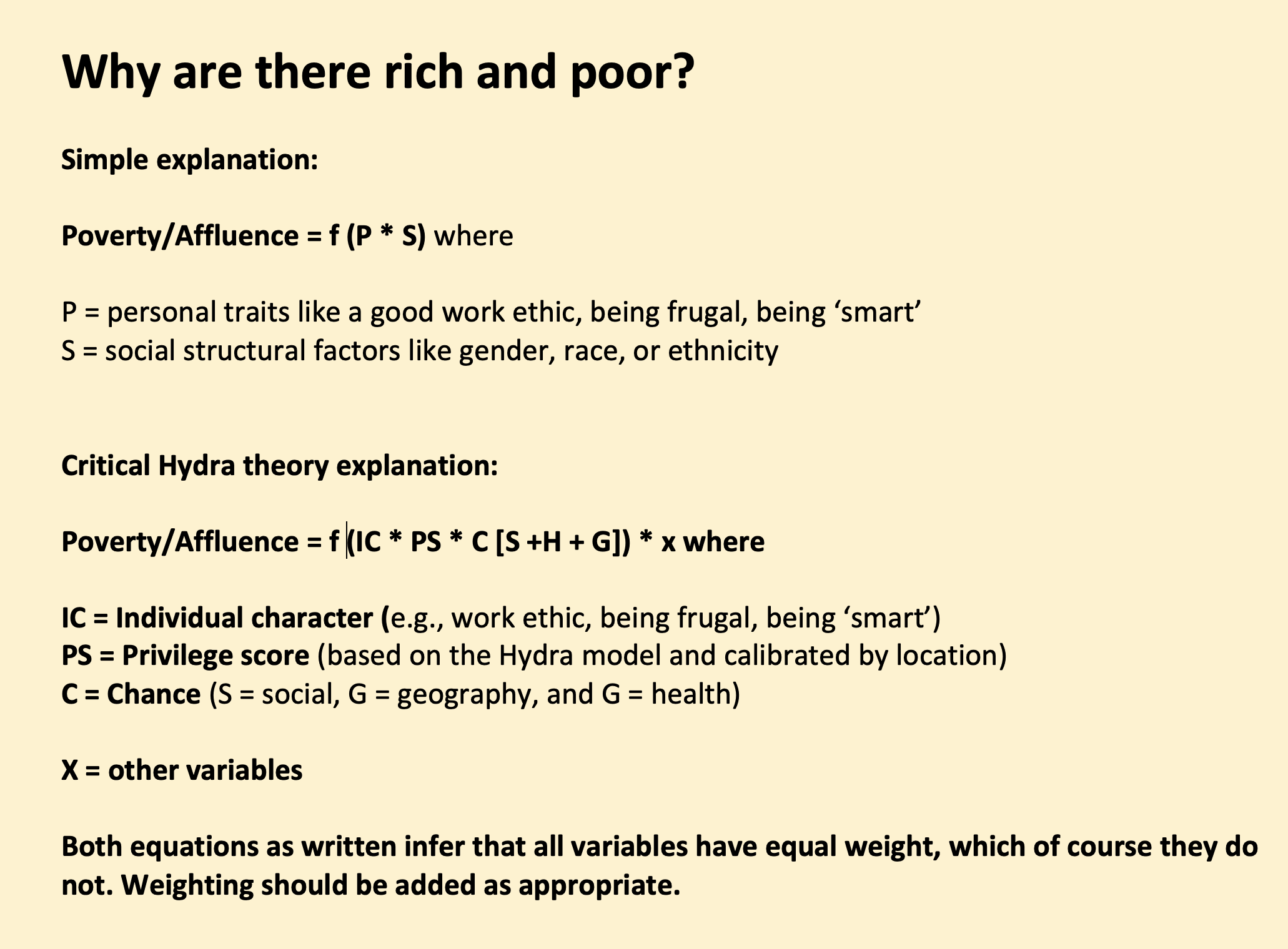

In a video for the class I presented an equation explaining social stratification. In the very simplest form of this equation I present one way to answer the question ‘why are there rich and poor?’

Poverty/Affluence = f (P * S) where

Poverty/Affluence = f (P * S) where

P = personal traits like a good work ethic, being frugal, being ‘smart’

S = social structural factors like gender, race, or ethnicity

Put into words, Poverty or Affluence of a person is a function of two general variables namely personal qualities (or lack thereof) and social structural factors.

The Critical Hydra Theory explanation is more detailed.

Poverty/Affluence = f (IC * PS * C [S +H + G]) * x where

IC = Individual character (e.g., work ethic, being frugal, being ‘smart’)

PS = Privilege score (based on the Hydra model and calibrated by location)

C = Chance (S = social, H = health, G = geography)

X = other variables

Put into words, Poverty or Affluence of a person is a function of individual character, the privilege score of the individual (where all the heads of the Hydra represent various statuses, and chance factors such as social context (e.g., number of siblings, birth order, social relationships, and so on), health (mental, emotional and physical), and geography (where a person is born/lives, e.g., urban, rural, and a myriad of other dimensions).

Both equations as written infer that all variables have equal weight, which of course they do not. And demonstratively so, weighting matters a great deal. Using the simpler model to explain poverty or affluence, the question to ask is that if these two variables (P and S) are not equal, which should be weighted more, which is the more influential variable?

Those who defend the stratification system, mostly the rich, will argue that P is more important and that they are in their position because of a strong work ethic and in general being being frugal and smart, that is, superior humans. The poor tend not blame themselves and thus see S as being the dominate variable by far though acknowledging the influence of personal effort.

The Critical Hydra Theory view is that not only one’s relative wealth but more than that, what sociologist Max Weber called one’s ‘life chances‘, are determined mostly by social forces and hence the simple equation would look more like this:

P/A = f (P * 10S), with poverty or affluence ten times more influential than personal character.

In sum, all humans are impacted by power and the social forces put in play by the use and abuse of power by individuals and groups who find a way to exploit differences and turn differentiation into stratification. Personal character matters, but it is far outweighed by many external variables, mostly privileging forces.

Power and social forces

The dynamic described above, allowing for the marginalization of some humans by others, has played out throughout human history. Structured social inequality is the product of toxic othering, itself the product of the perhaps inexorable process of status differences being used to justify the inferior treatment of those deemed ‘less equal.’

Critical Hydra theory demands an understanding of power and the social forces that lead to structured social inequality. But looking at only the present is not enough, the critical Hydra theorist must look deep into the history of each culture, this task becoming increasingly difficult as the process of globalization accelerates.

Thank you

I’ll conclude by again thanking the 20 learners -14 Rohingya refugees and 6 host community Bangladeshis- in Bangladesh joining me in this journey of exploration and understanding. Their inspiring questions continue to push our analysis and understanding forward. Critical Hydra theory is maturing because of this special class of women and men, some refugees, other members off the host community, all joining together to move themselves and all of humanity in a more positive direction.

This and all of the posts categorized in Hydra “privileging forces” will soon appear in Understanding and Taming the Hydra to be published late summer 2021.

Follow

Follow