The root causes of toxic othering: Narratives of Rohingya and Bangladeshis

Guest post by Mohammad Azizul Hoque[1]

Ascribed status and identity politics

“Why have I have become a stateless refugee in a world of 195 countries? Why have I been confined by persecution in my motherland Myanmar and beyond? I ask my friends and family, but none of them can soothe my inquisitive mind.” A Rohingya refugee asked this question while Professor Thomas Arcaro and I were facilitating an online sociology course for underprivileged refugee and host community youth in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. “Our hopes and aspirations are identical to other human spices of the Earth; however, because of our ethnicity, we are rejected, displaced and persecuted,” commented another student.

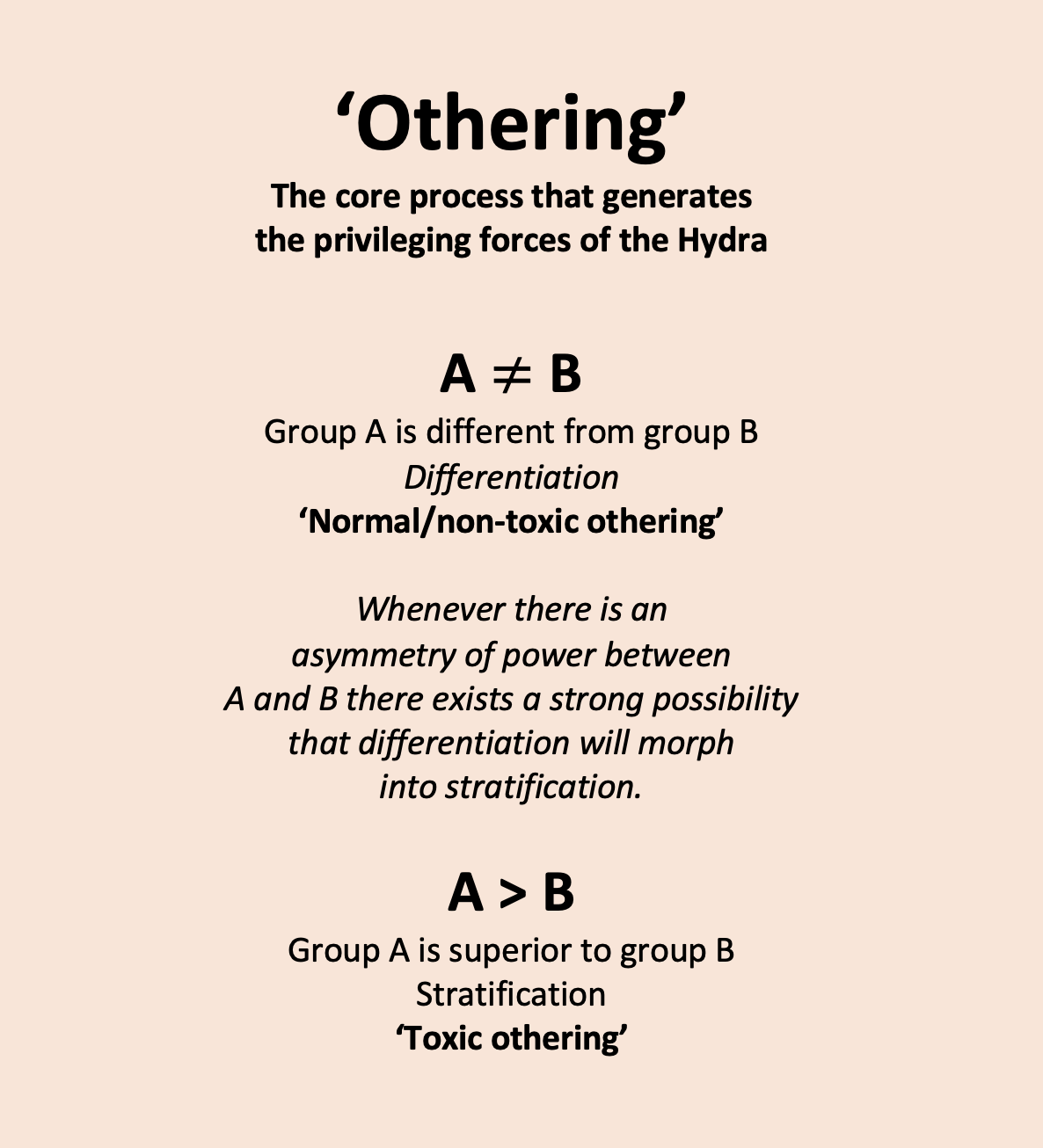

Their words triggered us to apprehend how the ascribed status of “Rohingya” has become the cause of needless discrimination. Professor Arcaro replied, “Being a refugee or stateless is an ascribed status which you neither earned nor chose. Rather, it has been determined by the dominant groups in society and as a result, minorities are often assigned lower statuses.” A Bangladeshi participant said, “Life under an ascribed status is not a bed of roses, but one of terrible spikes and fences.” Toxic ethnocentrism-fuelled identity politics based on language, religion and ethnicity in Myanmar, which manifested in reaction to deliberate political and military manoeuvres, have been largely backed by the Bamar (or Burmese) majority polity of Myanmar, a diverse nation comprised of hundreds of ethnic groups.

Iris Marion Young (1990) said that ascribed status of a minority ethnic group like the Rohingya makes them vulnerable to cultural imperialism (including stereotyping, erasure, or appropriation of one’s group identity), violence, exploitation, marginalization, and powerlessness. Similarly, Francis Fukuyama (1992) addressed religion and nationalism as the two leading components of identity politics. Robert H. Taylor (2005) articulated that, after independence of 1948, Burmese’s ruling forces were generous in handling the rights of the Arakanese Rohingya. However, in 1962, a new political transformation occurred when the Burmese military took over the political administration in a coup and embarked on a decades-long period of totalitarian rule, characterized by discriminatory campaigns against the country’s non-Bamar groups. Consequentially, the military’s ethnocentric identity politics led to the annulment of citizenship and nationality of Rohingya, and ultimately led to their deportation and ethnic cleansing.

Ethnocentrism, exclusion and power distance

“Social power and resources are unequally distributed in our society,” a Bangladeshi female student said. “Whether it’s monsoon flooding, pandemic, or political instability, the destitute are always more affected than social elites, who

can use their money and power to overcome crisis. The peripheral people cannot overcome the effects.” Here, social  elites are privileged not only due to their wealth but also their membership in different dominant groups such as ruling parties, majority ethnic groups, affiliations with dynastic political and business families, roles in public administration, and other politico-economic associations. They often misuse their political power and commit nepotism in order to seize social resources; on the other hand, people at the bottom of the power hierarchy accept these imbalances as foregone.

elites are privileged not only due to their wealth but also their membership in different dominant groups such as ruling parties, majority ethnic groups, affiliations with dynastic political and business families, roles in public administration, and other politico-economic associations. They often misuse their political power and commit nepotism in order to seize social resources; on the other hand, people at the bottom of the power hierarchy accept these imbalances as foregone.

In a society where corruption is deep-rooted, a citizen hesitates to approach powerful bureaucrats and political representatives to claim the civic services to which they should be entitled. A Bangladeshi participant said, “If we challenge the roles of social elites, they may retaliate violently.” In other contexts, disenfranchisement is legally enshrined altogether. In Myanmar, stateless Rohingya lack even basic legal entitlements to protection by the state, driving an intoxicated sense of impunity amongst the vigilantes and extremists who commit atrocities against them. Ethnocentrism has mushroomed alongside toxic-othering so that Bamar Buddhists, the majority, are perceived and promulgated as the superior ethnicity. As a Rohingya student said, “Powerful groups use religion to justify the claim that other ethnic groups, such as Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, and other religious minorities, are of foreign origins and have not been recognized as identity groups with rightful claims to Burmese nationality.”

Through Facebook and national media outlets, the state has deliberately inflamed anti-Rohingya hate speech and propaganda towards the “othered,” non-recognized groups, particularly followers of Islam (Reuters, 2018). A Rohingya student said, “In Rohingya areas, the military regime localized and tailored its human rights abuses and discriminatory rule by imposing restrictions on religious conversion and inter-faith marriage.” Extremist nationalist propaganda functions to validate the fears harboured by the majority Buddhist population about the threat of a Muslim takeover of the country. As it transmits propaganda, the state implicitly sanctions social prejudice and inter-communal violence against Muslims (CFR, 2020). Another Rohingya student said, “Both communities (ethnic Rakhines and Muslims) feel that ‘the other’ is threatening to their identities, particularly their religion and culture.” The key contestations have always been around equality (how power and resources are shared) and acceptance (how ethnic, religious and cultural identities are respected (UNDP & Search for Common Ground, 2015).

Ideological divide and confrontational politics in Bangladesh

Confrontation, hatred and blame games have been a common practice in Bangladeshi politics. Members of the “big others” (a small group in terms of the money and muscle power they hold) dominate the “small others” (who are large in size but remain at the bottom of the power hierarchy) through policy and law and by manipulating the state apparatus in their own favor. Political leaders have carried out elements of toxic othering at the local level in the name of both pro and anti-liberation movements, as well as religious ideologies, which are transmitted from the centre toward the periphery as tools to manipulate voters. Broadly described, these othering processes feature a wide array of confrontation, competition, and monopolization of state institutions and resources by the party in power, which uses every possible state apparatus to marginalize the opposition (Arfina Osman, 2010). This trend has tremendously weakened formal accountability mechanisms, escalated a sense of impunity among political cadres, and put governance in crisis.

Bangladesh has earned remarkable GDP growth and infrastructure development in recent years; however, the gaps between wealthy and destitute have escalated simultaneously. A Bangladeshi student said, “As power has been an effective tool of wealth accumulation, youths of middle and lower classes – particularly from urban areas – have become desperate to join government services or politics by any means.” Political leaders personalize state power by creating networks and alliances to meet their objectives (Islam, 2013). Another Bangladeshi female student said, “If there are two candidates in a municipal election, people will vote for the high-income candidate despite his poor education, competency and honesty.” Voters think that only the wealthier is capable to donate relief-good if they are affected by cyclone or flood. Hoque (2016) argued that some cunning candidate struggle to manipulate large poor voters with lump sums incentives like strait cash, token-money, wheat or rice as a shortcut tool of clientalism ahead of election. On the other hand, during the national election, mainstream political parties become desperate to win by hook or by crook. Because banally winner takes all and they monopolize state apparatuses with politically affiliated people.

Gender-based discrimination and false concepts of women’s role in society

From a symbolic perspective, patriarchy has been a powerful privileging force in Rohingya and Bangladeshi families living in Cox’s Bazar that results in gender-based discrimination, violence and marginalization. Unlike in more central areas, women in outlying and rural areas tend to be exceedingly underprivileged and suffer from poor health, illiteracy, and lack of participation in social and political decision-making, which persists in many spheres and poses particular challenges. “Rohingya women have forgotten how to speak publicly,” a 20-year-old female refugee student said. “Our women and girls are always excluded from decision-making forums, either in the home or in the social sphere. Neither family nor community elders think it significant to take girls’ consent on social and cultural matters.” A recent study (Olney and Hoque, 2021) addressed the escalation of gender-based violence in Rohingya families during the pandemic. A Rohingya woman said, “We, as women, are always the victims of domestic violence when there is any misunderstanding or impoliteness between a wife, her husband and in-laws.”

In many cases, false consciousness is the root cause among Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi host families in Cox’s Bazar where some people think that, “Men have inherent authority to beat their women to correct their behavior,” according to one student. “Gender inequality starts from men’s toxic mind-sets.” A refugee student said, “Women have to talk in a lower voice, always. Their husbands could get angry even if their wife expresses that she is ill.”

Some students commented that societal discrimination against women leads families to marry off underage daughters as a strategy to ensure their protection, further compounding the same subjugation they hope to avoid. As another female student said, “Parents are prompted to marry off their daughter’s right after puberty, because they are concerned for their security and economic burden.” These dynamics consequently escalate the power distance between sexes, where women remain at the bottom of the power hierarchy and continue to be obstructed from accessing basic rights and education. “Men torture their wives whenever their parents disagree with her about something, or when he orders her to bring something to him from her parents and she can’t bring it due to poverty.” Bangladesh has formulated various laws, policies and affirmative actions for women, which have significantly reduced the rate of violence against women, but there is still much room for progress.

Toxic othering as a colonial legacy

From a comparative perspective, Bangladesh and Myanmar are confronting different challenges; however, their  underlying politico-cultural pathologies are identical. Both countries were colonized by the British Indian Empire, which cultivated toxic othering between communities through divide and rule policies, which systematically broke up larger concentrations of power into pieces that individually had less power than the implementer of the strategy, enabling the empire to secure its dominion (Christopher, 1988).

underlying politico-cultural pathologies are identical. Both countries were colonized by the British Indian Empire, which cultivated toxic othering between communities through divide and rule policies, which systematically broke up larger concentrations of power into pieces that individually had less power than the implementer of the strategy, enabling the empire to secure its dominion (Christopher, 1988).

The British purposely created fractions between ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities in the occupied territory by promoting prejudice and toxic othering, destroying congenial relations between groups, gerrymandering geographic polities, and denying traditions to distract populations with infighting amongst themselves that prevented them from uniting in order to challenge the regime. Indian scholar and politician Shashi Tharoor (2017) write that the creation and perpetuation of Hindu-Muslim antagonism in British India was one of the most significant accomplishments of British imperial policy: the “divide et impera” (divide and rule) strategy facilitated continued imperial rule and reached its tragic culmination in 1947. Until 1857, there were no communal problems in India (Katju, 2013). Katju notes that although there were differences between Hindus and Muslims, with Hindus going to temples while Muslims went to mosques, participating in different festivals, and members of the two groups always helped each other and held no animosity.

Conclusion

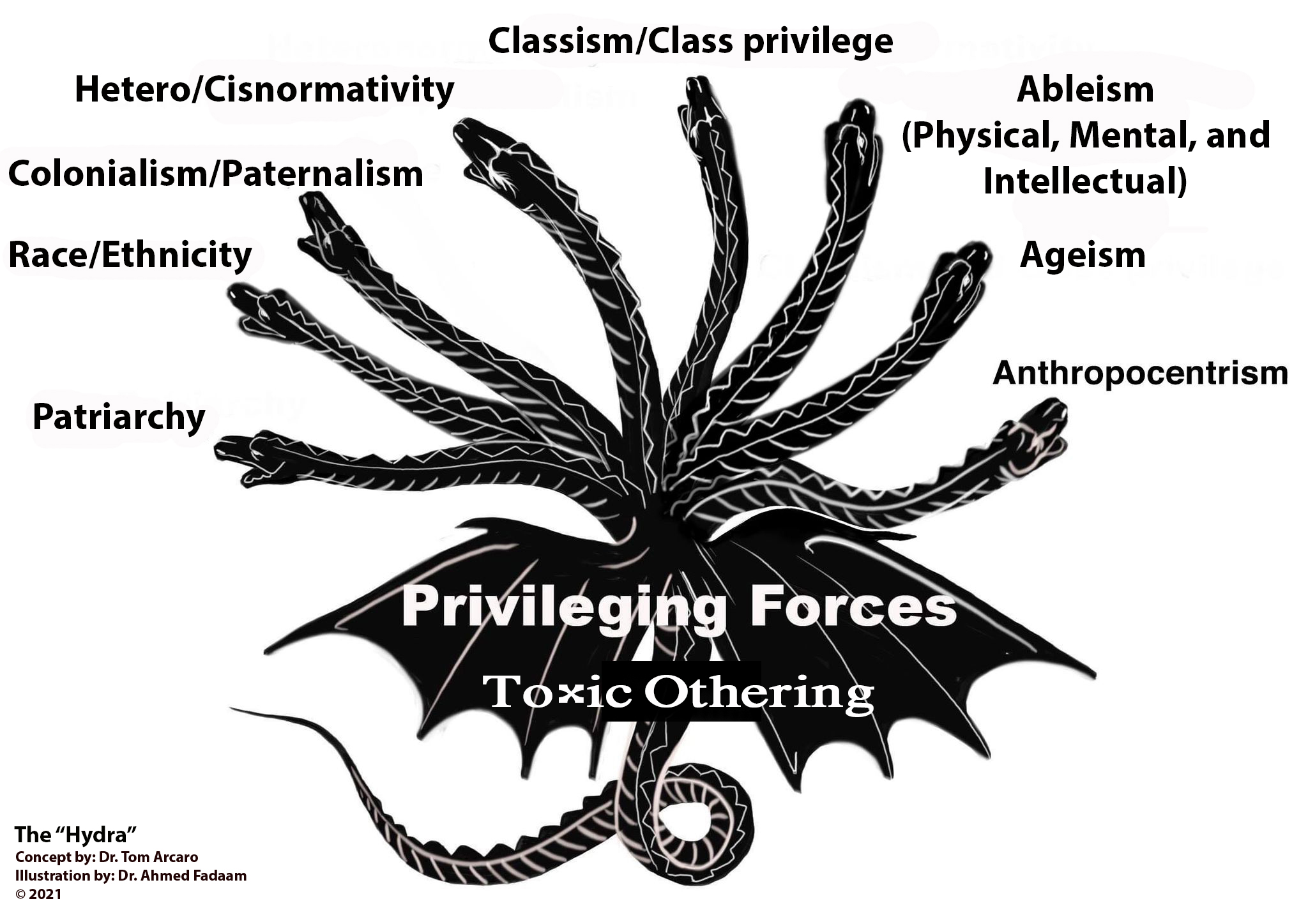

A Bangladeshi participant said, “I wish I were able to defeat privileging forces.” In response to that, Professor Arcaro said, “I have realized that the hydra, or privileging forces, never end in Myanmar or in Bangladesh. It is a cultural universal. However, we can pacify the hydra to make it more innocuous.” A refugee participant commented on the intergenerational transfer of the hydra’s power in Myanmar: “While General Ne win was brutally persecuting Rohingya people, our people thought that if he retired, the atrocities would stop. However, Ne Win has now gone, but many subsequent hostile persecutors emerged.” Now, efforts to mainstream social cohesion can contribute to a nation’s resilience in the face of internal divisions and conflicts. Such efforts have the potential to present a more coherent vision of a nation’s future to its diverse peoples.

References

1. Arfina Osman, F., 2010. Bangladesh Politics: Confrontation, Monopoly and Crisis in Governance. Asian Journal of Political Science, [online] 18(3), pp.310-333. Available at: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02185377.2010.527224>.

2. CFR, 2020. India’s Muslims: An Increasingly Marginalized Population. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/india-muslims-marginalized-population-bjp-modi> [Accessed 7 August 2021].

3. Christopher, A. (1988). ‘Divide and Rule’: The Impress of British Separation Policies. Area, 20(3), 233-240. Retrieved August 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20002624

4. Fukuyama, F., 2018. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018, 240 pp. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

5. Hoque, M. (2016). Tea Politics and Clientelism. [Online]. Dhaka: The Daily Independent. Retrieved 14 August 2021, from https://www.theindependentbd.com/magazine/details/45983/Tea-politics-and-clientelism.

6. Islam, M., 2013. The Toxic Politics of Bangladesh: A Bipolar Competitive Neopatrimonial State?. Asian Journal of Political Science, 21(2), pp.148-168.

7. Katju, M., 2013. The truth about Pakistan. The Nation, [online] Available at: <https://web.archive.org/web/20131110103720/http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/columns/02-Mar-2013/the-truth-about-pakistan> [Accessed 7 August 2021].

8. Olney, J. and Hoque, M., 2021. Perceptions of Rohingya Refugees: Marriage and Social Justice After Cross-Border Displacement. [online] San Francisco: The Asia Foundation & Centre for Peace and Justice, p.12.

9. Reuters, 2018. Why Facebook is losing the war on hate speech in Myanmar. [online] Reuters. Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-facebook-hate/> [Accessed 7 August 2021].

10. Taylor, R., 2005. Do States Make Nations?. South East Asia Research, 13(3), pp.261-286.

11. Tharoor, S., 2017. The Partition: The British game of ‘divide and rule’. Al Jazeera, [online]. Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/8/10/the-partition-the-british-game-of-divide-and-rule> [Accessed 8 August 2021].

12. UNDP & Search for Common Ground, 2015. SOCIAL COHESION FRAMEWORK social cohesion for stronger communities. [online] Yangon: UNDP, p.18. Available at: <https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SC2-Pariticipant-Guide_English.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2021].

13. Young, I., 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. 1st ed. PRINCETON; OXFORD: Princeton University Press.

[1] Mohammad Azizul Hoque is a Research Associate at Centre for Peace and Justice, Brac University. He worked with Professor Thomas Arcaro as an interpreter for Bengali and Rohingya speakers and co-teacher of Sociology. Email: azizul.hoque@bracu.ac.bd

Follow

Follow