[updated 14 August 2021]

Retroactive application of critical Hydra theory

More on what my learners are teaching me

As I approached the task of talking explicitly and in detail about the Hydra with the learners in Bangladesh, I found myself going back to my ‘greatest hits’, ideas that had stead me well over the decades teaching sociology to mostly privileged US undergraduates.

I realize now, more deeply than I’d like to admit, I was part of a culture that taught about power and privileging in a very traditional way, that is to say ignorant to the history of how deeply and thoroughly asymmetrical and toxically marginalizing power had been embedded itself into every fiber of all world cultures. I knew the world was not fair but had not demanded of myself an examination of my own blinders and preconceptions. Knowing something in the abstract is very different from experiencing it in real time discussing topics with my learners.

A quick point, though. We are all creatures of the culture in which we were born, the weltanschauung in which we were socialized, our way of understanding the world absorbed deeply into our consciousness. In his book Ishmael Daniel Quinn uses with great effect the image of ‘Mother Culture’ whispering into our ears, providing each of us many subtle but critical unwritten assumptions about our world. Our common task is to learn the ability to be critical of our selves and the culture in which we live. Indeed this is the very reason I have taught this and all of my classes for the last 40 years about C. Wright Mills’ sociological imagination, about how to see the world beyond the lenses of our own culture. But this task is not easy or without risk. As anthropologist Jules Henry put it long ago, “To look closely at our culture is to grow angry and to anger others.”

My colleague Azizul and I talked about how gaining critical thinking skills was indeed one of the main goals we had for our learners and how using these skills in daily life may set some of them apart from their peers, making them ‘deviants’. Through history successful agents of social change have always been positive deviants, and we talked to the learners about how those fighting for democracy now in Myanmar are exactly that, women and men going against what the government says in order to fight the injustices and oppression. Given the in depth and frank discussion of gender based violence (GBV) we had in our recent class session -many of the comments going from the females in class- I am confident this cohort of learners has the courage to, as appropriate, speak true to power. I have not urged them to cause ‘good trouble’ as John Lewis would say, but I am not doubting some may choose this path.

Learners or students?

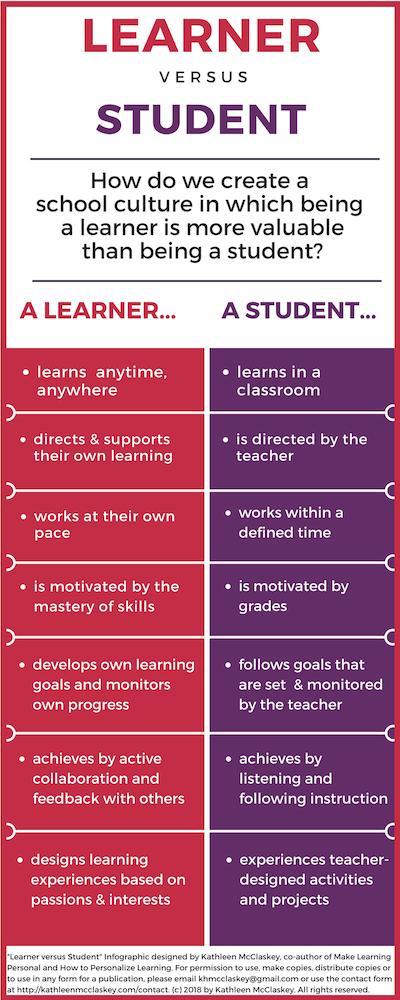

Why use the word learner as opposed to student? When we were planning our first communications for our class I referred to our ‘students’ but my colleague Azizul shared that the word ‘learners’ would be more appropriate. I had

seen this term used in various international contexts but always defaulted to the US norm of using ‘students’. I researched the difference and found that learner, as defined in this graphic, perfectly described my hopes for those who are in my classes, learns anywhere (!), at their own pace, motivated by the desire to learn and so on. Though Azizul liked and shared this distinction between student and learner his explanation as to why we need to use learner points out a political and diplomatic reality.

“We do not use Student publicly for a couple of reasons. “Student” is related to a formal academic activity like school, working toward a degree in Bangladesh. On the other hand, Rohingya are not allowed to access formal education so far. However, they are allowed informal skill-building workshops, training, learning initiatives. Therefore we called our Rohingya either volunteers or learners. On the other hand, learners implies a more self-driven approach whereas the student is topdown. Thus, using learners, we wanted to make them proactive in learning. We do not teach however we facilitate their teaching-learning process. We learn collectively.”

There is much already written -with much more to come from both academic researchers and from those affected- about the many truncated rights of refugees, but our current experience with this cohort of learners highlights the limitations on the right to advanced education. This is an inherently political issue deserving of careful discussion at the highest levels.

Azizul, Trevor, and I have been interacting with a mixed group for the last several months -14 Rohingya refugees and 6 Bangladeshi nationals, males and females in each sub-group. As a statement of fact, some in our class have more rights than others. That this is so is in itself a delicate issue, one that I feel we have handled with utmost care, modeling a hyper conscientious egalitarian approach to all our class interactions.

Retroactive application of critical Hydra theory

As I write this Taliban forces reacting to the power vacuum created by the US withdrawal are retaking much of Afghanistan by force. Primarily controlled by the men from one Pashtun ethnic group, the Taliban is a political movement that has altered world history by its use of violence against both outsiders and those within who would rebel.

But see what I just wrote? A fairly ‘traditional’ statement about the Taliban which, looking now through the lens of critical Hydra theory, I argue glosses over the centuries (millennia?) old baked in misogyny which has subjugated women into second class persons. I will die on this hill: the treatment of women under the Taliban is not, as a cultural relativist might say, benign gender differentiation. We need to describe it as it is, stripped of male dominated cultural justification. Taliban treatment of women is overtly and toxically gender stratification.

Here is what I wrote nearly 40 years ago on this general topic. I have indeed come full circle.

“To thoroughly embrace the idea of relativism is to rationalize and justify a repressive and even destructive status quo in most cultures, at the very least with respect to the way women are treated.” [Here is the original essay.]

There is an old story from anthropology that I sometimes tell my students about how ethnocentrism is a cultural universal; all human groups have pride in themselves and tend to see ‘others’ as less than. Back to the basic definition of ethnocentrism as “if A B therefore A > B.” The story comes from the British anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard describing his study of the Nuer in east Africa, asking them what the word their people used for their culture “Naath” meant. Their response was it meant “the people.” Prichard asked for clarification, pointing out that though he was not Nuer but was not Nuer. They replied politely, ‘no you are not people, you are not quite human.’

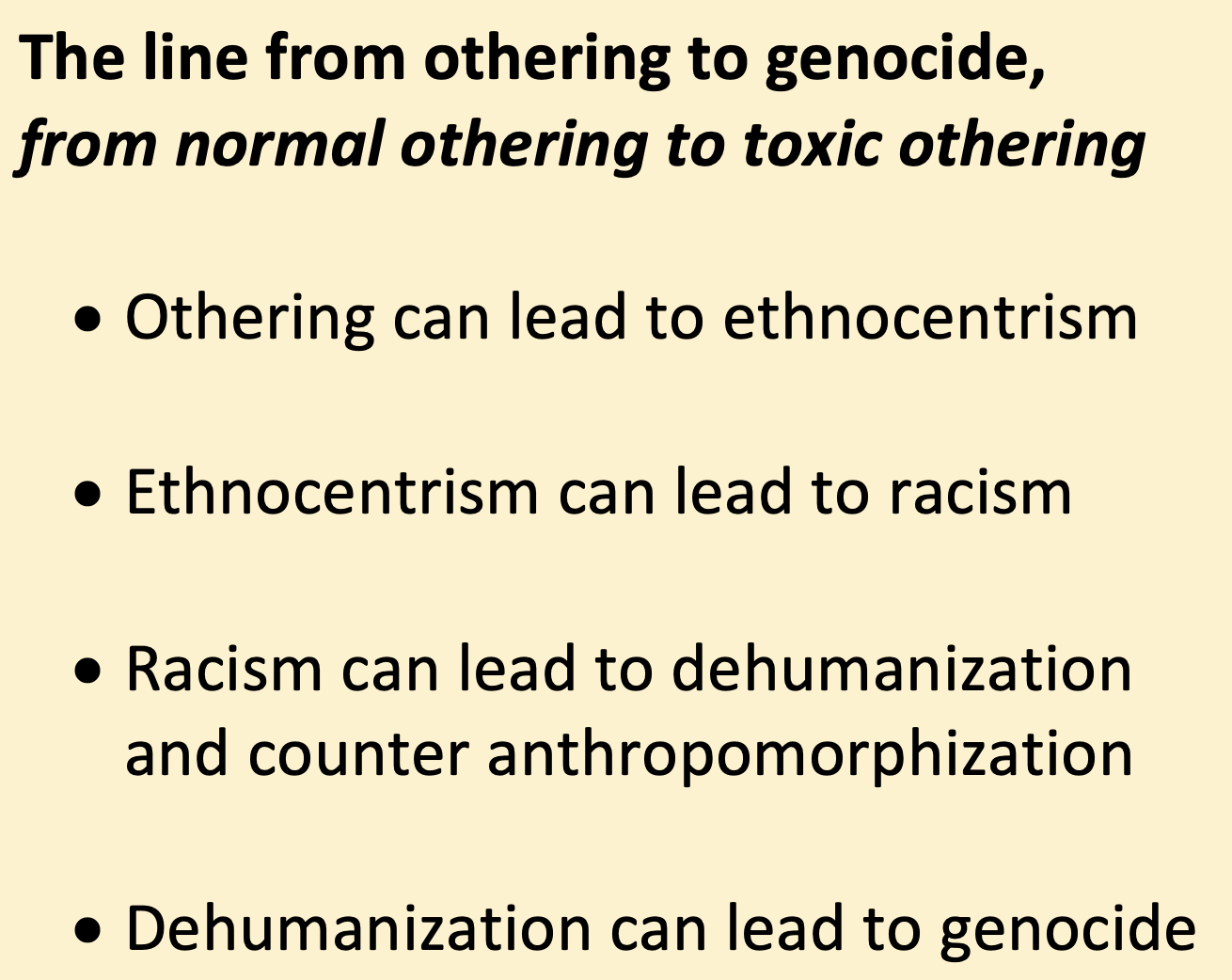

As I pointed out to my Bangladeshi learners, the line from othering to ethnocentrism is pretty direct, as is the line

from ethnocentrism to racism. Through the entirety of human history cultures like the Nuer have embedded a low-grade version of racism into their world view, this becoming more toxic as we see the long, bloody global history of slavery and genocide in not just the continent of Africa but in much of the rest of the world.

Human character is not a monolith, and there is a range of personality types which appear to exist among humans. Though necessary perhaps for group fitness in early epochs of our existence during the period of our development as a species, the existence of a personality type which enjoys power and control seems evident. Just as we find handedness to be a cultural universal -most efficiently explained using the concept of group (not individual) fitness- the same is so for the small but significant percentage of the population with a strong need for power.

As we transitioned from mostly egalitarian hunting and gathering lives (through several stages) to agricultural lifestyles, the problem of how to distribute the surpluses generated by the domestication of both plants and animals was solved by those who wanted power by creating and justifying various forms of social stratification. These personality types have long dominated the global landscape, and by looking at their movement through history we can see the bloody consequences of colonization driven by the lust for power these men had/have. Our poster child example here is perhaps King Leopold of Belgium who is responsible for the decade long genocide of perhaps 10,000,000 Congolese in the late 1800’s. Leopold has much competition for his ignoble title of worst, as we turn to Mao, Pol Pot, Hitler, and others.

Back to the Taliban, their leadership, by systematically only pulling from one ethnic group, both outwardly and inwardly show overt signs of ethnocentrism, it but a thinly veiled racism. The Taliban appears to be primarily controlled by the men from one Pashtun ethnic group. To be clear, the Taliban have highjacked Pashtun and Afghan culture, and cancerous misognistic, racist, and classist privileging forces have taken root. The story of the racist and misogynistic Taliban is neither new nor uncommon; it can be seen countless times in cultures long before they came into existence and other examples fill every corner of the entire globe.

And so, we now see that the three main privileging forces representing the key ‘isms’ taught in most intro to sociology classes are all embedded inextricably in all world cultures. Race, gender, and class dynamics are central to the vast majority of socially structured inequality we find virtually everywhere. These three privileging forces continue to work in tandem with each other and all of the other privileging forces to sustain the many layers of marginalization which characterize human life. In the last several centuries the internal logic of capitalism and, more recently neoliberalism, have exponentially amplified all these forces, especially so classism.

An application of critical Hydra theory to our global history demands deconstructing our species’ history of toxic othering and how these acts of marginalization have been normalized and even glorified by leaders, past and present. This deconstruction effort is not easy, fast, simple, nor uncontroversial, but taming the Hydra, I believe, can be accomplished.

Follow

Follow