Teaching an online sociology course in Bangladesh

Introducing ‘critical Hydra theory’

Midterm update from Elon/Cox’s Bazar/Bangladesh

My teaching assistants and I are over just halfway through our experimental 10 week short course ‘introduction to sociology.’ Our class is comprised of 20 learners, 14 of them are from Myanmar, Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazaar, and the other six are Bangladeshi nationals. The class also has a mix of males and females, though not unpredictably so males dominate in terms of numbers.

Our class meets synchronously via GoogleMeets or Zoom for approximately 1 1/2 to 2 hours each week. There are the usual technical difficulties on both ends, but in the refugee camp especially Wi-Fi connectivity is iffy in the best

times, and during hard rains, etc. the connections are sometimes poor or lost all together. As if on cue, the call to prayers comes through someone’s microphone at least once each class. Keeping all 20 students for the full amount of time is pretty much impossible, but we are doing our best. In addition to the chronic Wi-Fi issues my refugee learners are currently on lockdown because of Covid.

I have two extraordinary teaching assistants helping me with this class. Here in North Carolina is Trevor Molin, a former student of mine. He volunteered to help with this class as part of the service component in my Global Social Problems class this spring and is now helping me on this end on a totally volunteer basis.

My other teaching assistant is Azizul Hoque, who has been given time from his other duties at the Brac University Center for Peace and Justice based in Dhaka to fix, translate, and otherwise make the class happen in Bangladesh. Without Aziz the class could not happen. Period. His ability to translate my sometime high level vocabulary into both Bangla and Rohingya is nothing less than amazing; he never hesitates and rarely asks me for clarification. The three of us have a great working relationship, and typically meet (via WhatsApp) several times each week both before and after our weekly synchronous class.

Our text is an OpenStax free text -Sociology 2e– which I edited down from 450+ pages to about 140. We had this modified text printed and bound in Cox’s Bazar and distributed to our students. The learners have been asked to read approximately one chapter per week and also watch the 4-5 short videos I create to add and clarify content.

We have our challenges. But the overall vibe of the class is that our time together is extraordinarily valuable and we all make an effort to do what we can to make our class happen. Bangladesh, of course, is many hours ahead of the

US, so although we meet in the late afternoon for the learners it is an early morning class for me and my Elon teaching assistant Trevor. We get up at 5:00 or 5:30, start the coffee, and join the class at 6:00 AM.

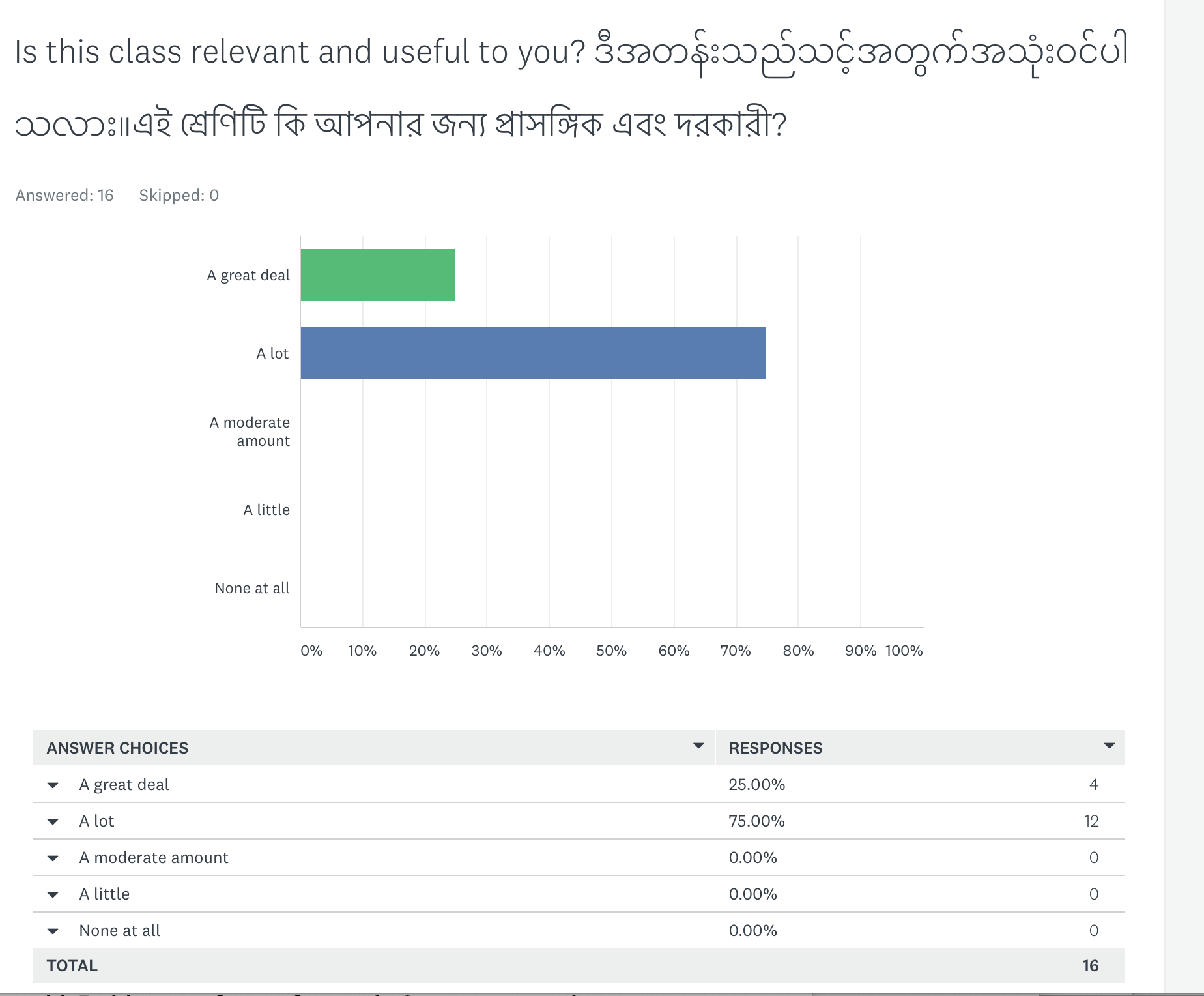

We had a good response to our mid-session student perception of teaching survey (80%) and overall earned very high marks. When asked, Overall how would you rate your experience in this course? ယေဘုယျအားသင်ဤသင်တန်း၌သင်တို့၏အတွေ့အကြုံကိုဘယ်လောက်သတ်မှတ်မလဲসামগ্রিকভাবে আপনি এই কোর্সে আপনার অভিজ্ঞতা কীভাবে রেট কর 81% indicated ‘very valuable’ and remaining 19% said ‘very valuable.”

Another key question was, “Is this class relevant and useful to you?”. Here are the results.

Some background and context

I have been writing about and working with Rohingya refugees for nearly 2 years now and my relationships led me to Jessica Olney, a fellow with the Center for Peace and Justice (CPJ) at Brac University in Bangladesh. Jessica visited my Global Social Problems class this spring at Elon University via Skype, and we talked about, among other things, creating an online class for refugees. Our plans became reality just after the end of Ramadan this spring we started a grand experiment that is made possible only by support from Brac University the the CPJ.

Currently across the globe 80 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes -about 1% of humanity- and at any time there are approximately 7 million living in managed refugee camps. The harsh reality is that the average stay in refugee camps is counted in years and even decades, not months or days.

The humanitarian organizations administering the refugee camps have all manner of tasks to accomplish to keep a camp functioning. Top on their priority list is safety and security, but WASH, shelter, food, and camp organization and communication are all very high priorities. Lower on the priority scale is keeping everyone occupied. In the case of adults there are many ‘cash for work’ programs where refugees work with NGOs to do necessary tasks around the camp. I have written about these refugees and have called them refugee humanitarian‘s.

Younger people of course need to be taken care of, and there are various NGOs which focus on daycare, kindergarten, and primary education (e.g., Save the Children and World Vision). Secondary and tertiary education are far down on the priority list. That’s where this class comes in. I am teaching both refugees and Bangladeshi nationals that are in their late teens and early 20s, hungry to learn, but with limited pathways to further themselves educationally. To my knowledge ours is a unique class, bringing together refugees and nationals.

Toxic othering

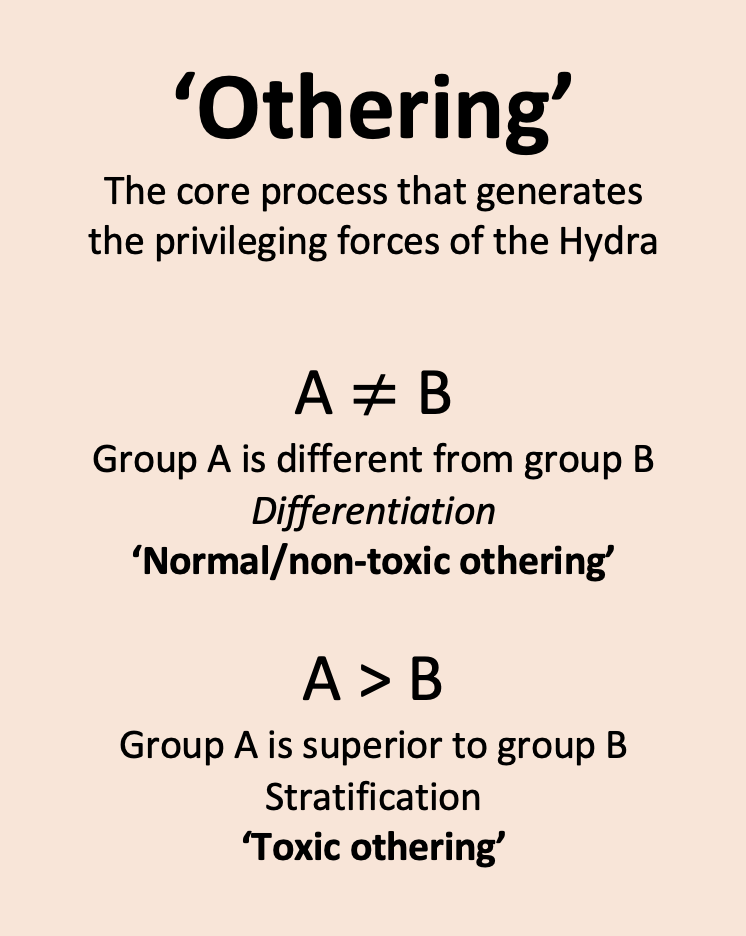

Today in class we talked about the content of chapter 6 in their text (Social Organizations), and I was describing the basic sociological terms of ‘in group’ and ‘out group.’ I have not talked to them yet about the Hydra model, but in a previous video lecture I introduced him to the concept of ‘othering.’ Today we talked about how one group tends to ‘other’ another group. I then went on to differentiate between ‘normal othering’ and ‘toxic othering.’ I described to

them how in much simpler simpler words, differentiation is very different from stratification. That is, seeing differences is normal and typically OK, but using differences to justify seeing people as inferior or marginalizing them is bad, it is toxic othering.

them how in much simpler simpler words, differentiation is very different from stratification. That is, seeing differences is normal and typically OK, but using differences to justify seeing people as inferior or marginalizing them is bad, it is toxic othering.

After class I talked to Aziz about how he explained othering in Bangla and the Rohingya language. He said that he had to first understand it himself, but through my examples where I talked about how one sports team is different from another sports team, and seeing your team as naturally better is part of how we all function. We are all a bit ethnocentric, for the most part benignly so. In the same way we can be a bit centered toward our other ascribed and achieved statuses, sometimes just ‘normally’ but all too frequently our othering become toxic, especially when there are scarce resources at play.

The same thing can be seen in the example of the family where families do things in slightly different ways. I made the point that it is a matter of perspective; we are the ‘other’ to those in different groups that we ‘other.’ People naturally see that groups can be different. Seeing and acknowledging these differences in others is normal othering. Toxic othering is seeing the other as inferior and not just different.

Going to the macro level, I used the example of colonization as toxic othering on a global level, pointing out that the British colonization of much of India and Southeast Asia (and elsewhere, of course) was a classic form of toxic othering, where one group saw that they (British) were different from another and made the assumption that this made them superior to the other (those living on the subcontinent of India) and used that assumption to justify and rationalize the colonization of these people. The irony that I was conducting this class in English was offered as another example of an oppressive colonial legacy.

Going to the macro level, I used the example of colonization as toxic othering on a global level, pointing out that the British colonization of much of India and Southeast Asia (and elsewhere, of course) was a classic form of toxic othering, where one group saw that they (British) were different from another and made the assumption that this made them superior to the other (those living on the subcontinent of India) and used that assumption to justify and rationalize the colonization of these people. The irony that I was conducting this class in English was offered as another example of an oppressive colonial legacy.

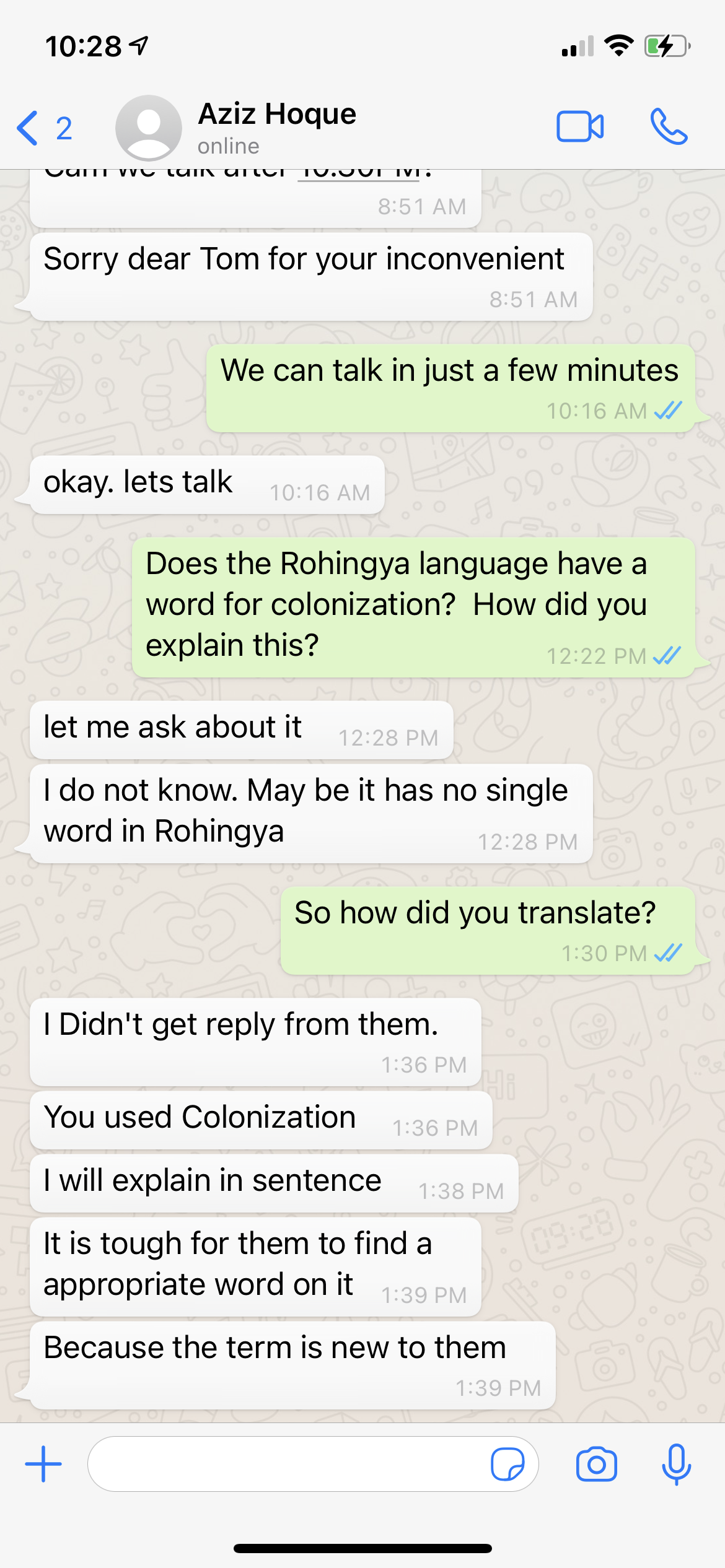

My teaching assistant and translator later told me that the Rohingya language has no word for colonization. I find this to be both disturbing and a bit surreal given the fact that their lives are impacted in such a major way by the legacies of colonial control.

Here is what my US teaching assistant Trevor Molin had to say about this class,

Yesterday, I learned that many of the individuals I’ve been helping teach don’t have a word for colonizer in their language. A word that bares a history of hundreds of years of death and cultural erasure, a word so linked to the present conditions of these people, Bangladeshi and Rohingya alike. A word thrown around carelessly at times in the States, of a false identification of our forefathers as fighting against the colonial forces of the British Empire, when, all they truly did win the autonomy of their own colonial force. There are dozens of sayings speaking of the lessons that must be learned from the past, but for those learning in the virtual class with me today, a word doesn’t even exist to identify one of the greatest drivers of the way that they live today.

This class has been an eye-opening one to me, particularly in learning about the cultural differences between myself and those who are being taught. Each day I learn another way in which our education differs, or norms differ, our families differ, and today, how our language differs.

At the end of the day Aziz was able to convey the concept of toxic othering very well to all of the learners, and I even had a couple of them give examples. One young woman talked about how the males in her life tend to see her as different and not as capable. Her father encourages her and sees her for the full human that she is, but he is an exception. A young man gave the example that as a Rohingya he was othered (also know as genocide) by people in Myanmar, in particular by the Tatmadaw, and that has led him to have to flee his homeland.

Here is how Aziz describes the challenge of translation,

“Being involved in the course, I realized that the success of learning depends on the use of appropriate language (e.g. first language) or medium of communication between learners and instructors and which helps learners to relate content to their context.

While I interpret, identifying appropriate words in the Rohingya language to interpret many English terms like culture, colonialism, and socialization was a regular challenge. Indeed, Rohingya is a dialectical language that does not have an available written alphabet. Therefore, it absorbed numerous foreign words e.g. Arabic, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali and Burmese and it has been a Hybrid. Sometimes, I had to use one more word or small sentence and example to interpret a single English term. Before attending the session, I had to collect words on the subject either from Google or sometimes asking my family and friends in Cox’s Bazar to know how they use the words in their conversation. However, translating into Bengali was easier for me as it has the available vocabulary to interpret from any language.”

I knew that this class would pose pedagogical challenges for me, and indeed it does, but my task is by far much easier than that of Aziz. he has to not only understand the points being made but immediately find a way to translate these complex concepts into now one but two other languages. He handles this task with grace and unmatched professionalism each class.

Critical race theory and critical Hydra theory

Critical race theory and critical Hydra theory

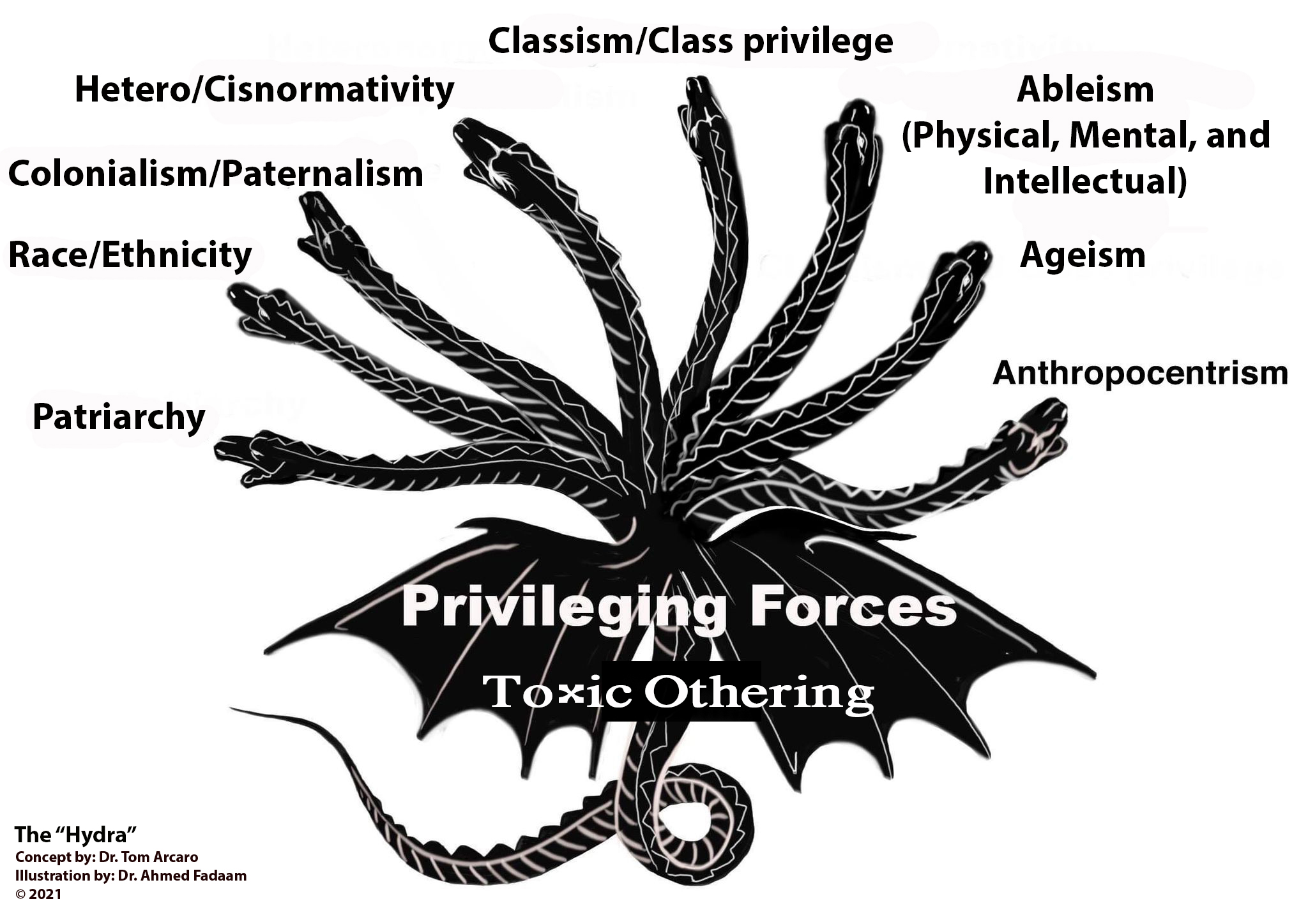

So yes, I was teaching critical race theory today in my sociology class. The Hydra model developed in some detail in this blog [and in the soon-to-be published Understanding and Taming the Hydra] is indeed a call to understand how privileging forces of patriarchy, race/ethnicity, hetero/cisnormativity, classism, ableism, ageism, and anthropocentrism have all been generated by toxic othering and are indeed impacting the lives of everyone on the planet, negatively so people like the Rohingya and other refugees around the world.

Critical race theory deals directly with one head of the Hydra but also, done well, emphasizes the inevitable and inherent intersectionality of racial and ethnic histories. You can’t effectively cover critical race theory without talking about the history of toxic colonialism, for example. Critical Hydra theory involves looking at how toxic and marginalizing othering is represented by all the heads of the Hydra and is evidenced in long standing norms, policies, and laws which have normalized and justified various forms of discrimination, exclusion, marginalization, and even genocide; toxic othering. These socially structured inequalities exist in all cultures to varying degrees, and so critical Hydra theory in necessarily global and demonstratively historical in scope.

The overall intent of this certificate course is not to create ‘mini sociologists’, but rather better community leaders, with a deeper sense of who they are and the social forces that impact them and their communities. My deepest hope is that what we are learning in this class about various pedagogies, what works and what does not work, will eventually inform and contribute to other classes being offered by faculty persons from around the world. I firmly believe that critical race theory -and critical Hydra theory- have a central place in this and any future classes.

Understanding and Taming the Hydra is going soon. Watch this space!

Follow

Follow