Maybe local aid workers could do most expat roles better and more cost-effectively

by @arbiebaguios

Tom and I recently launched a survey that solicited the perspectives of national and local Filipino aid workers on a range of issues within the aid sector – in particular, the (in)equalities that exist between expat and local staff.

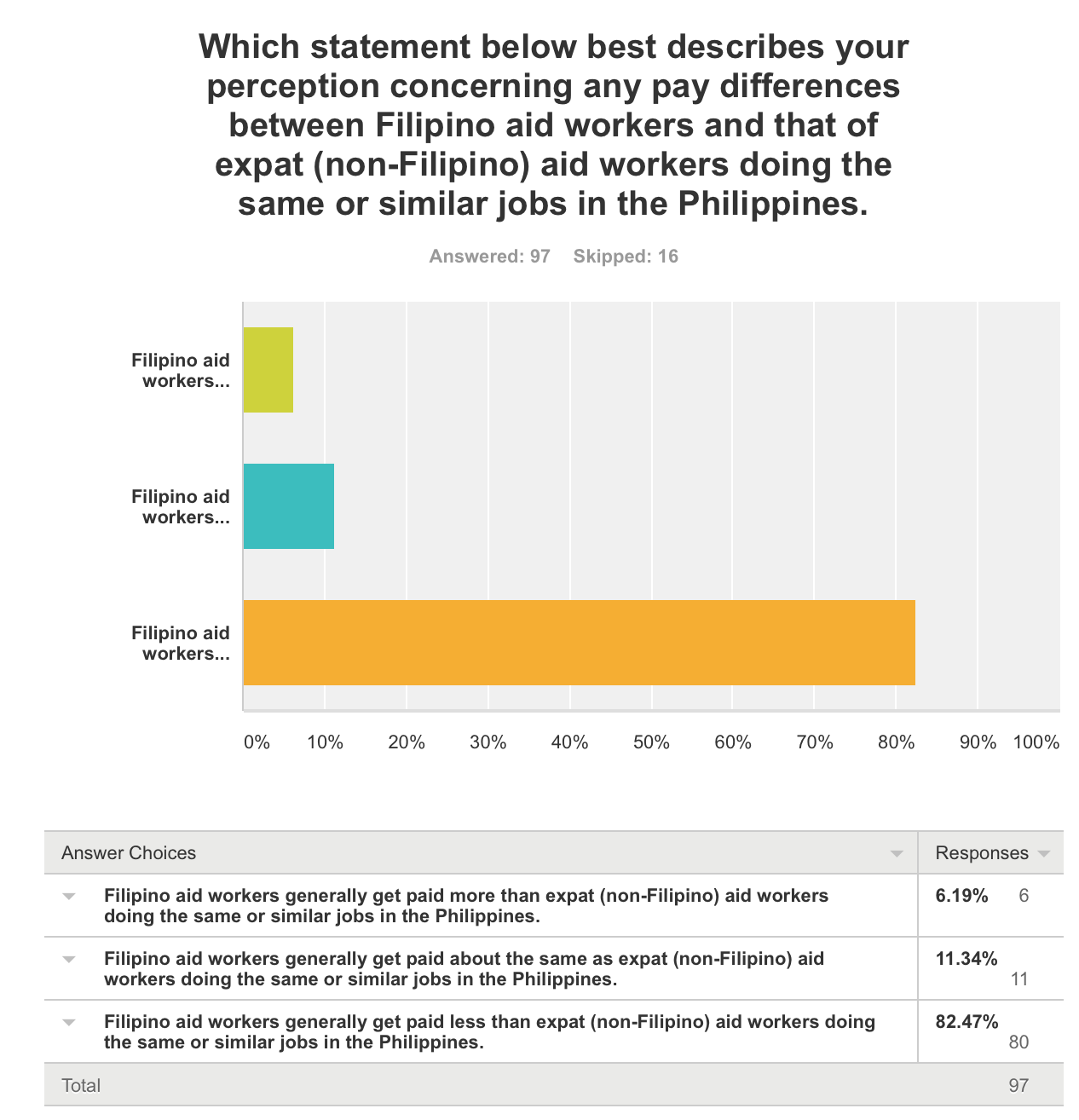

In a previous blog, we highlighted the ever-present issue of expat vs local staff salary. Our survey’s preliminary findings suggest that local Filipino aid workers think they are being paid less than their expat equivalent for doing the same work. Throughout the years, many blogs, articles and research have attempted to dissect this issue – and as the most recent Guardian piece from Tobias Denskus says, it’s complicated.

His article is one of the most nuanced ones to date to discuss this: it recognises the increasing ‘localisation’ of aid; highlights the changing dynamics of labour in our globalised economies; and acknowledges the pragmatic considerations of expat pay (being away from home, working longer hours, etc). I actually agree with most of what he’s written, especially with the crux of his analysis: “We need to think about how we can move the debate forward beyond salaries.”

I concur, so let’s.

Here’s my hypothesis: local aid workers can do most expat workers’ job just as well, in a more cost-effective manner, and in a way that maximises aid programmes’ ownership and accountability.

Although this is only a hypothesis – I do not have scientific evidence to back this up (yet), apart from my own observed and lived experience; and also, well, I could be wrong – and therefore would appreciate constructive discussions around this issue.

Now, let’s go back to the question from the survey: “Which statement below best describes your perception concerning any pay differences between Filipino aid workers and that of expat (non-Filipino) aid workers doing the same or similar jobs in the Philippines.” Key phrase: the same or similar jobs.

What this tells us is that it’s not just that local aid workers are aware that they are being paid less than their foreign colleagues, but that they think they are being paid less for virtually doing the same job as expats. So, looking beyond why expat staff are being paid more than local staff, I would like to ask: why hire expats?

I pose this question in the context of the Philippines where this survey was taken: it is a newly industrialised country whose economy (per GDP) is 36th largest in the world, above Singapore, Finland or Luxembourg. Of course that is not to say that the Philippines’ level of development by conventional measures is at par with those countries – after all, it still has a high rate of poverty, high rate of inequality, low per capita income, and generally weak public welfare systems – although this does give us an idea of the capacities that exist within the country. As Tobias wrote in his article, “Skilled professionals for project management, IT and creative industries are already in demand in growing economies across Africa and Asia, and the relatively small aid industry will have to offer incentives to attract and retain local talent. A new generation of internationally educated, global professionals with local language skills is sought in many sectors.”

Full disclosure: I am a Filipino. And yes, I’d like to believe I could do an expat’s job in the Philippines just as well. In fact, I’m an “expat” now, although I went the other way: I am one of only a handful of Global South citizens working at a large humanitarian organisation’s headquarters in London; I have worked in my current role for close to a year now, after having been promoted from my junior position. And this is despite the fact that I started out my career as a local staff in the Philippines, and I’m not even internationally educated (I only have a bachelor’s degree from a university in Manila – which, for non-work related purposes, I had to pay £200 for so that it can be recognised as equivalent to a UK degree)!

Here’s the thing: I am not an exception. I personally know so many well-educated, adequately-skilled, highly qualified fellow Filipinos who could fill – and excel in – “expat” positions within international NGOs in the Philippines. The country is especially teeming with eager, passionate, capable young people who are keen to contribute positively to their own society.

But the reality is this: international NGOs offer a pitiable salary compared to, say, the private sector. Now – in this globalised economy where people from both Global North and Global South alike want iPhones or aspire to backpack around the world – suppose you’re a young Filipino fresh out of a really good university: would you rather begin to build your career as a local staff for an INGO and receive a low pay, or work for a multinational corporation and receive generous compensation that affords the products of a globalised economy? For many of the Philippines’ competent young labour force, the choice is easy to make. (Although the good thing is, despite the pay differences, many still choose to work for non-profits out of their motivation to help others).

So, I go back to the question I earlier posed: why hire expats? I imagine that even if an INGO matches a multinational corporation’s salary for local staff, it would still be cheaper than paying for an expat. At the same time, local staff provide the added benefit of understanding the local context and culture; potential for greater engagement with target populations (instead of beneficiaries feeling “obliged to be grateful” to foreign aid workers); and greater ownership of aid programmes.

Then again, it’s complicated. The humanitarian sector is part of wider complex social, political and economic systems; at this very moment, I wouldn’t be able to say what the full far-reaching implications are if INGOs hired local staff for expat roles. I also acknowledge that in the business of emergency response (particularly in sudden onset disasters), there is still an added value from expats’ technical proficiencies.

But I am bringing up this relatively radical idea to highlight that contexts like the Philippines now have strong existing capacities (which I’m sure the many years of INGOs’ “capacity building” has improved – so if anything, those interventions in the past worked!); and that maybe we need to rethink how current INGOs operate in these particular contexts. Maybe it’s time to imagine an alternative to the default configuration of what Evil Genius calls the “humanitarian ménage a trois” of donors, implementers and beneficiaries, to wit, where are the local actors in that?

One phrase from Tobias’s article caught my attention: he wrote that despite the increasing localisation of aid and the rapidly changing world we live in, “expat aid workers will continue to exist.” I can’t help but wonder: is he saying that as long as low-income countries receive international aid funding, then expat aid workers will continue to exist? Or is he saying this in a broader sense – that expat aid workers will continue to exist indefinitely?

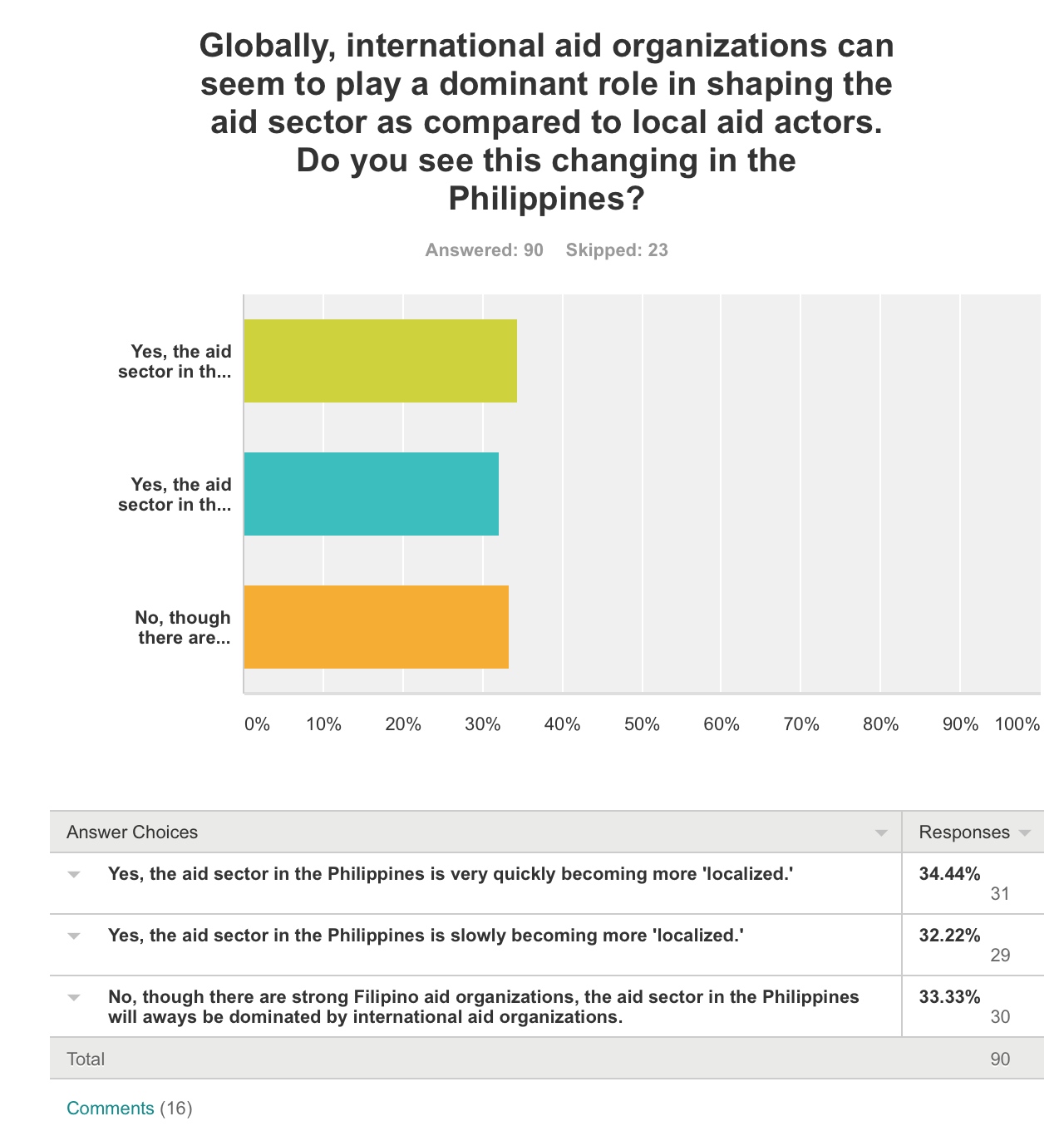

As a citizen of the Global South, I am motivated to work within the international development and humanitarian sector towards the goal that aid-receiving countries such as my own will progress in such a way that we won’t need international assistance in the future anymore (or as much) – just like the US or the UK or much of the “developed world.” I’d like to think this is what my fellow countrymen aspire for, too. In fact in our survey, a slight majority of Filipino aid workers think that the aid sector in the Philippines is “very quickly becoming more ‘localized’” as opposed to continuing to be “dominated by international aid organizations.”

And I hope our partners and colleagues from the UK or US or Japan or other traditional donor countries envision the same outcome for our society.

So does my hypothesis – that local aid workers can do most expat roles better in the Philippines – prove true? TBC, needs further research! But I definitely think it’s high time to acknowledge the changing, increasingly stronger existing capacities in countries like the Philippines, and have a frank, honest and constructive discussion about the international development and humanitarian sector’s way of working in the future.

I look forward to hearing others’ thoughts! You can contact me on Twitter @arbiebaguios or Tom via email or Twitter @tarcaro.

Note: Our survey of aid and development workers in the Philippines closes on Monday. Very soon after that we will be doing some posts about the results.

Follow

Follow