Methodology notes and ethnocentric assumptions

Some thoughts on the methodology

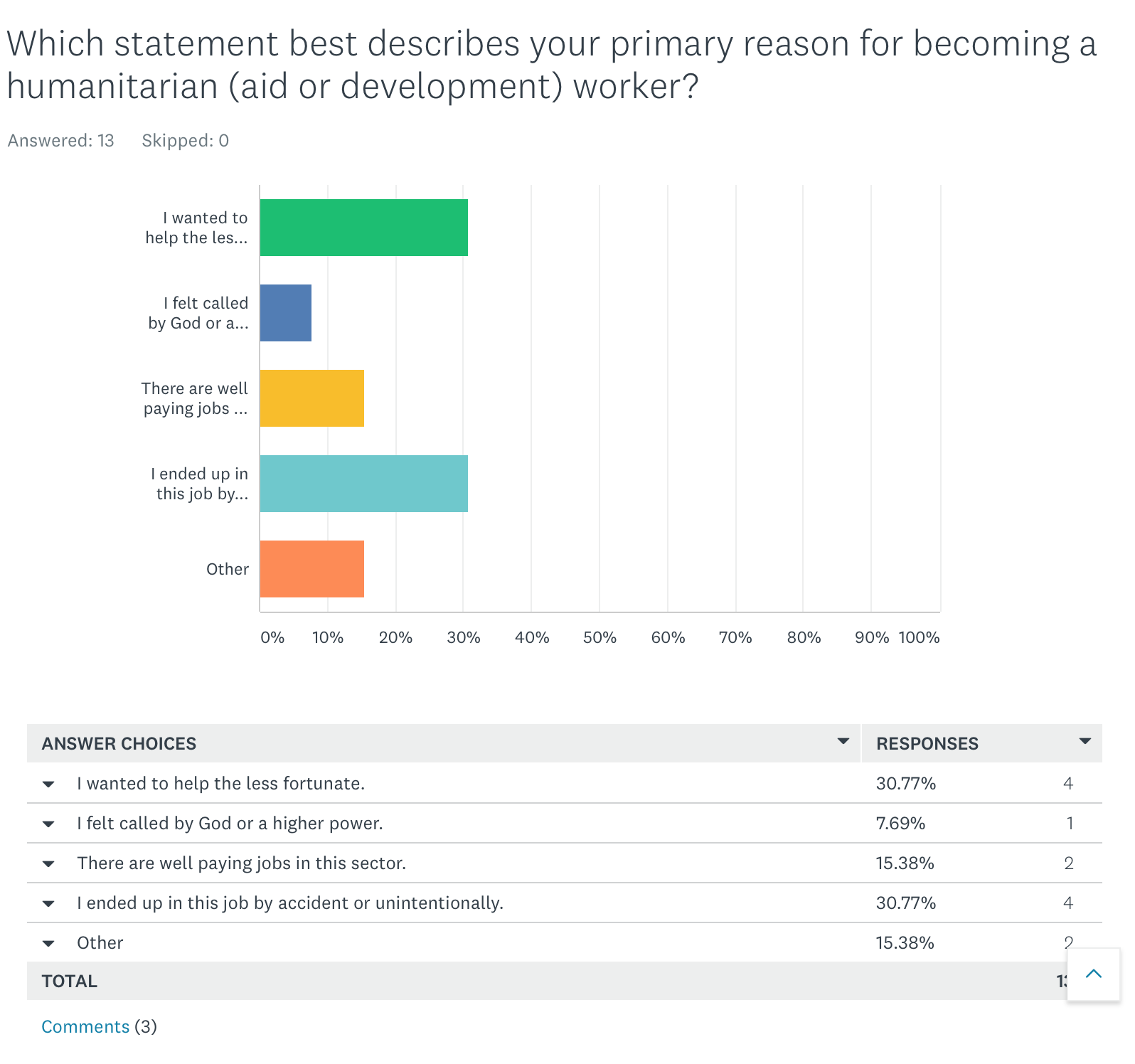

Our survey has been live now for a couple weeks, and the response has been, by any measure, weak. To date 40 people have started the survey (27 in the ‘long’ version and 13 the ‘short’ version, all in English).

Exploratory research

The target population for this global survey of humanitarians from the ‘global South’ is, well, exactly that. According to ALNAP there are over 500,000 national humanitarians serving globally. Realistically, there is no means possible to make every one of these women and men aware of this survey, nor would it be possible to translate the survey into the many dozens of languages and dialects used by this global population.

Translating the survey from English into Arabic, French, and Bangla makes it possible to reach, perhaps, a sizable majority of the half million national humanitarians. That said, we can never be sure that the nuances of meaning in each question have been perfectly or even adequately captured in any of the translations, and so this is an additional necessary limitation of the survey.

For a survey to be properly generalizable, the responses must come from those who are representative of the overall population and reach a statistically representative sample of that population. Even if the survey were translated into all languages, it is not realistic to think that a majority have access to a computer or smart device and also a stable wifi connection sufficient to take an online survey.

For a survey to be properly generalizable, the responses must come from those who are representative of the overall population and reach a statistically representative sample of that population. Even if the survey were translated into all languages, it is not realistic to think that a majority have access to a computer or smart device and also a stable wifi connection sufficient to take an online survey.

So, to be clear, this research is -and has always been intended to be- exploratory and, as such, the data from the survey can best be used to describe broad, tentative patterns and to suggest further lines of inquiry.

Why take an online survey?

Why would any humanitarian take the time to complete a survey from a US based researcher? This is a key question, and given our response rate to this date, demands an answer.

But first, why not go through established pan-sector organizations to do such a survey? The quick answer is that would be perceived as a ‘top down’ initiative. My collaborators and I talked about the fact that it would be better if the survey was totally independent from any umbrella sector-wide entity, INGO or UN organization. For this research effort to be, and be seen as, an entirely independent undertaking, we thought, would increase the likelihood that people would feel less pressured to fill out the survey. But again, why should they?

Whenever anyone gets the invitation to fill out a survey -I do frequently here at my university- it typically comes in the form of an email with the survey link embedded. My first impulse is to do a quick cost vs benefit analysis. Some factors I -and I assume most others- consider include:

- How much time is this going to take and is it worth my precious minutes to complete the survey?

- What good can come to me personally by going through this effort?

- What ‘greater good’ can come to my organization (university, for example) from

my efforts? - What ‘greater good’ can come to other entities or to humanity as a whole as a result of my efforts?

- What will be done with the data that is being collected, and can these data directly or indirectly cause any harm to me, my organization, or to anyone else?

- Are there any personal questions being asked and if so, why? How will my personal information be used?

- Do I owe any social capital to the person (or organization) making the request and/or can I gain any social capital from the person (or organization) making this request if I complete the survey?

- Lastly, and perhaps most critically, from whom did this request come? Do I respect and trust the person or organization making this request of my time?

Who knows, this academic from the USA could be CIA or some other nefarious entity wanting to get information. As a potential respondent from the ‘global South’ when weighing the risk versus benefit factors going into the decision to participate -or not- it seems to be certainly a no brainer. Pressing the ‘delete’ icon and doing nothing is far less risky than filling out a survey from some American academic who might be working for a government agency.

Embedded ethnocentrism?

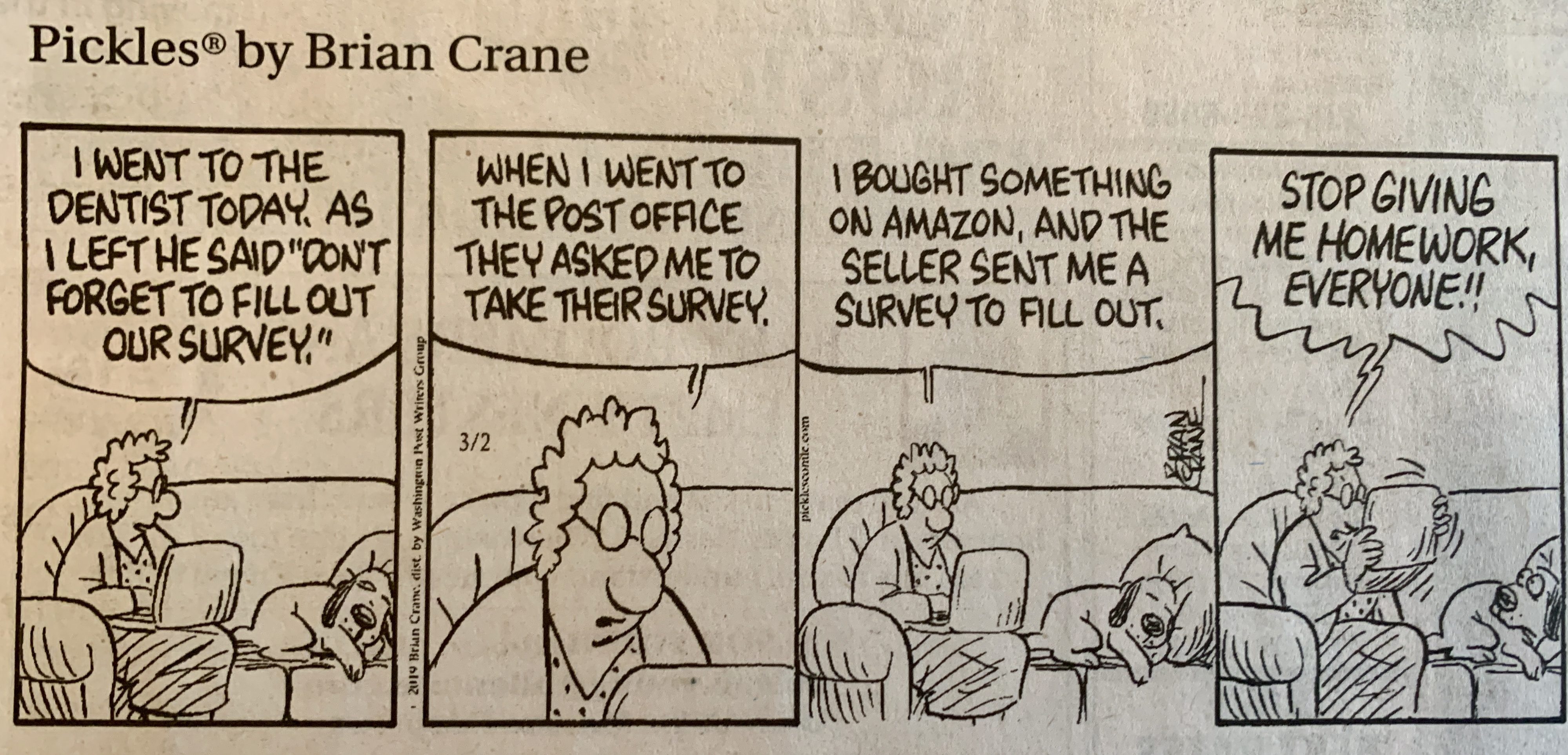

As a typical American and as an academic I get requests to take surveys very frequently

both from within my academic institution, my professional associations, and as a  consumer. Even from my doctor I get a message wanting me to complete a survey giving feedback on the service that I received.

consumer. Even from my doctor I get a message wanting me to complete a survey giving feedback on the service that I received.

That is all to say, in the United States we certainly have a culture of survey taking that makes it seem not unusual to have that request.

There is deep ethnocentrism embedded in my optimism that the survey will be well received by national aid workers globally. Indeed, why should it be? In many nations there does not exist nearly the same culture of survey taking, nor the luxury of being able to trust the source from which the survey is being requested.

In my next post (soon to come) I will provide some answers to the key question I raise above, namely why should national humanitarians invest the time to complete an anonymous survey. In the meantime contact me if you have any comments or questions.

Follow

Follow