Book length discussion of our survey results in the works NOW!

Drafting chapters now

All four research team members are drafting chapters as I write this. When the team met in Pittsburgh to present some preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion (SSSR), we decided that we want to share our data with the broadest possible audience. Everyone on the planet is impacted by religion either directly or indirectly, many struggling with their relationship to organized religion. We believe that many readers will be interested in first hand accounts of the many dimensions of this struggle.

Our data -over 1000 respondents to our English version and 154 respondents to our Portuguese version- is abundant with countless personal accounts, and we have chosen to present the data in book form. The lead chapter, setting the tone for the rest of the book, is being written by Jeff Wright, the catalyst behind this entire project. He is telling his story of his relationship with the church, why he wanted to do an online survey, explaining some of the reasoning behind the questions he wanted included, and finally, using some respondent narratives to illustrate his journey and many others who share his experience. We were blessed with many very passionate and articulate respondents who capture the important themes that emerged question after question, and Jeff -and the rest of the team- will use these anonymous respondents as real stars of the book.

Each of us, Jeff taking lead, will tell our personal stories and use our data to paint a picture for our readers, illustrating the many compelling themes that jumped out as we poured through the survey results question by question. By the end of the book the reader will have gotten to know each author, but more importantly the many, many respondents we will quote. Though we are sharing our personal stories, the quotations from our respondents will remain anonymous; no names were asked for or recorded.

Though our survey was targeted only to ex-Seventh Day Adventists, we believe the reader will find valuable and applicable insights no matter what their religion. SDA is unique, but it is also similar to other religions which hold great influence over their members. We invite the reader to find resonance and affirmation as they hear our stories and the many, many quotations from our respondents.

Our plan is to leave the reader feeling like they have been invited to hear the insights and stories of the both the authors and the 1000+ respondents. In reading these insights we believe the reader will find many comments and perspectives relatable and useful as they continue their own journey navigating a world in many ways dominated by the church.

Included in the book will be chapters on at least the following topics:

- Who took the survey and what did they look like?

- Why the survey and these specific questions? (Jeff)

- What being a non- Ex-SDA member of the team feels like. (Rene)

- A sociologist/atheist explores cults (Tom)

- A psychologist/atheist looks at arriving at non-belief (Duane)

- What people miss when they become ‘ex’ church members (Jeff)

- Sexual assault within the church (Rene)

- Psychological assault within the church (Rene)

- Respondent 666 (Tom)

- Reasons for leaving the church (Duane)

- Alyssa’s story (Guest on our blog)

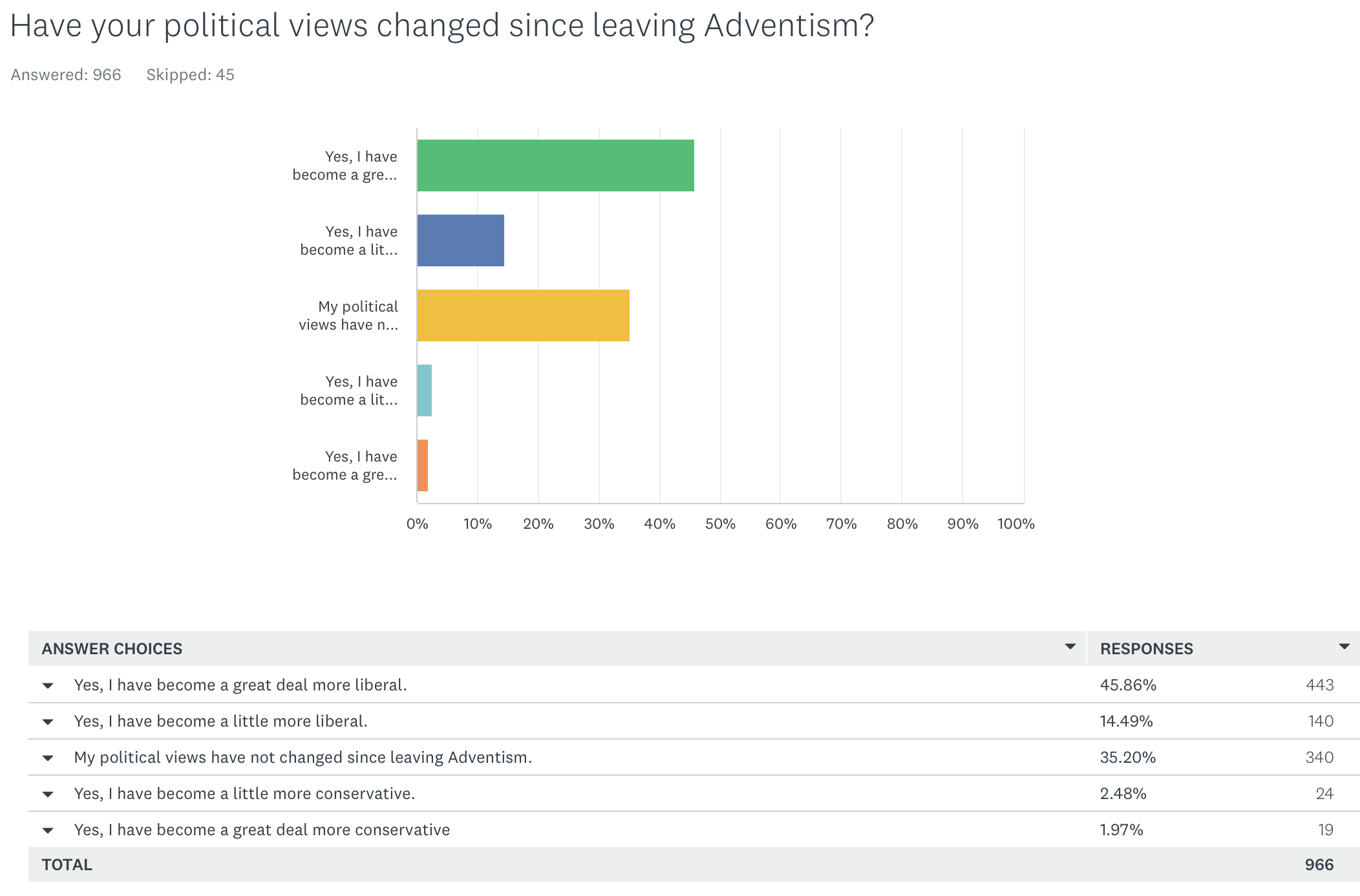

- Political views before and after leaving the church (Duane)

- The impact of being educated in church schools (Jeff)

- Differences between English and Portuguese respondents (Duane)

- The impact of the church on critical thinking skills (Tom)

- The impact of the church on social/environmental justice issues (Tom

- Questions left unanswered and/or unasked (Jeff)

This is just a tentative list (including authors) and ordering of chapters, but as you can see there will be topics of interest for any reader interested in what it means to be (or consider being) an ‘ex’ church member. More to come soon!

But first, some possible titles….

- Losing Our Religion

- Church Exit

- When is a cult a cult?

- Eighth Day Freedom

- Questioning the Church

- A New Life

- Haystacks Are Forever

- Betty White > Ellen White

- Breaking Free From the Church

Follow

Follow express the same views as that high school student on TV, in print, or in personal conversation. I remember after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center that an employee at my workplace sent an email to all several hundred employees enjoining us all to embrace the Bible and follow it as the “blueprint” for proper moral guidance and correct behavior. (I recall the word “blueprint” specifically.)

express the same views as that high school student on TV, in print, or in personal conversation. I remember after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center that an employee at my workplace sent an email to all several hundred employees enjoining us all to embrace the Bible and follow it as the “blueprint” for proper moral guidance and correct behavior. (I recall the word “blueprint” specifically.) Revised Standard Version, New International Version) he considered garbage. So here was a professedly devout Christian who adhered to a specific version (King James) of the Protestant Bible as his source for religious truth. The others were “garbage.” Harsh consideration for fellow Christians’ sources of inspiration, I would aver.

Revised Standard Version, New International Version) he considered garbage. So here was a professedly devout Christian who adhered to a specific version (King James) of the Protestant Bible as his source for religious truth. The others were “garbage.” Harsh consideration for fellow Christians’ sources of inspiration, I would aver. Christians. If all devout Christians were reading from the same precise and well-defined blueprint, they should be marching forward in lockstep, their minds in harmony regarding the proper ways of conduct. But they aren’t. Christians are very varied in their interpretations of virtually every aspect of the Bible, from major issues to trivialities. That is why so many Christian groups split off from others—differences of interpretation of scripture.

Christians. If all devout Christians were reading from the same precise and well-defined blueprint, they should be marching forward in lockstep, their minds in harmony regarding the proper ways of conduct. But they aren’t. Christians are very varied in their interpretations of virtually every aspect of the Bible, from major issues to trivialities. That is why so many Christian groups split off from others—differences of interpretation of scripture. related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights,” for Q 36.

related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights,” for Q 36.

Those subscribing to Christianity are falling as a percentage of Americans. To the extent that the former Adventists of our survey represent this secularizing trend, then we might predict a more politically liberal electorate as time goes on. This, of course, could have major ramifications in elections.

Those subscribing to Christianity are falling as a percentage of Americans. To the extent that the former Adventists of our survey represent this secularizing trend, then we might predict a more politically liberal electorate as time goes on. This, of course, could have major ramifications in elections.