“I really hope it will have more impact on the lives of more and more people. But nowadays it is more and more linked with political and economic agendas of the “powerful” countires so it is loosing its credibility. The use of the army also to bring humanitarian relief is it complicating and confusing people about what humanitarian work is.”

–(46+yo female expat aid worker)

“We are like the frontier doctors– right now we are “bloodletting” and have no clue how to help people, although we may accidentally have a positive effect. But, our efforts will enable future generations to learn from our mistakes– at least we are doing something!”

“Aid is getting smarter. Vast improvements have been made in just 10 years.”

“The field is becoming increasingly theoretical and ego-driven. Skills that actually save lives are being drowned out by debates on buzzwords.”

Aid worker voices on the future of humanitarian aid

Yes, all of the voices above need amplification, clarification and discussion. We’ll get to that.

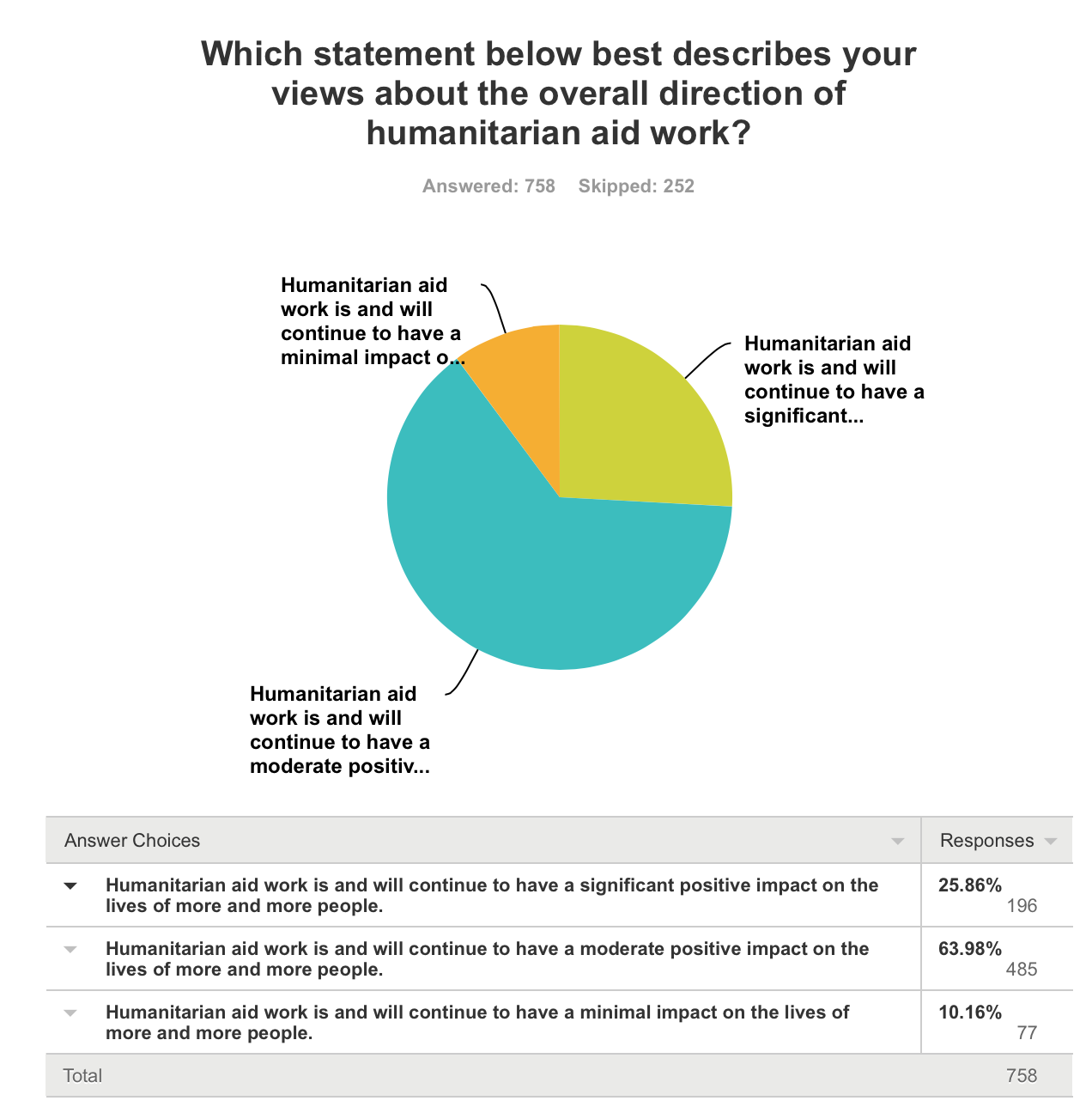

First, some numbers

Q59 and Q60 ended the survey by asking about the overall direction of humanitarian aid work, offering three response choices then a space for further comment. The modal response at 64% was “Humanitarian aid work is having and will continue to have a moderate positive impact on the lives of more and more people.” 26% indicted “a significant positive impact” and 10% reported “minimal impact.” Not overly positive, that. And so we end with some aid worker voices on our future, some of which are flip and humorous, some sober. But all are thoughtful in various measure.

Here are the data overall.

Here are the data broken down by gender, with females clustered slightly more toward the “moderate” response and males inflating the numbers on both extremes, “significant” and “minimal.” [For data wonks in the crowd, these differences were significant at the p = .05 level.] Looking at just the “significant” numbers it appears that females are much less confident than males. One wonders why this is so, and I have poured through the narrative responses trying to answer that question but have failed to arrive at any firm conclusion.

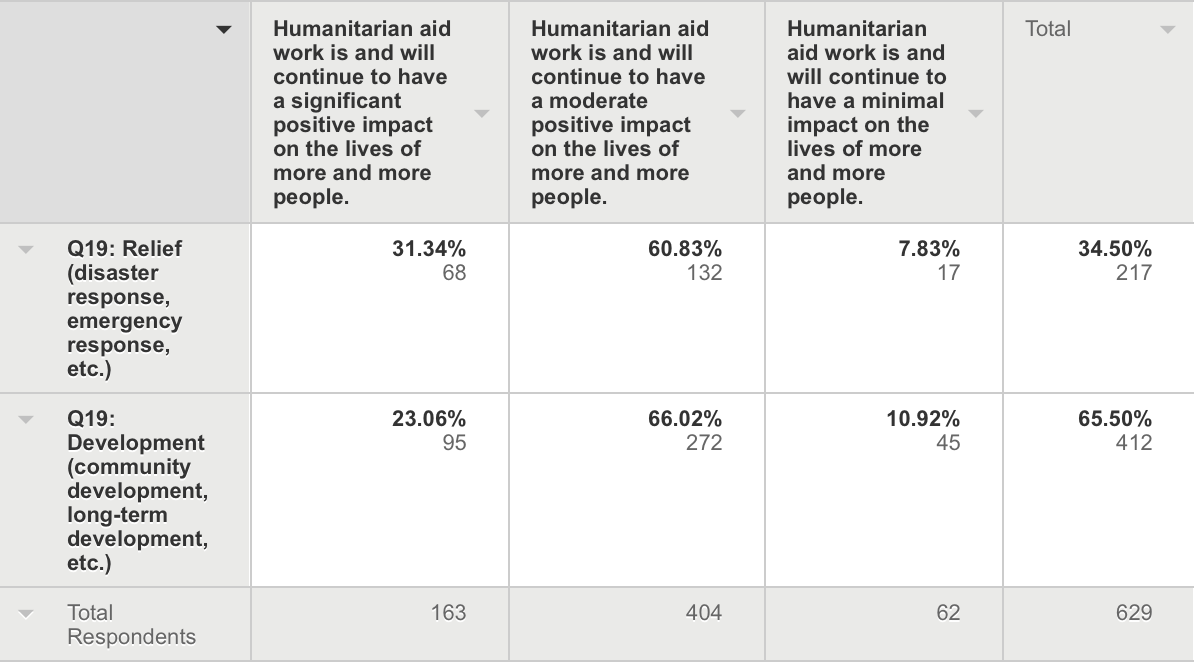

When I compared the results from those who identified as primarily relief workers as opposed to those doing development work the differences were, I think predictable. Relief workers -nearly a third of them- indicated “significant” as compared to only 23% of the development workers, and only 8% -as compared to almost 11% of the development workers indicated “minimal.”

That the overall numbers are so high -90% of the respondents indicating a moderate or more level of impact- is not reflected in many of the narrative responses discussed below.

Themes

Many themes emerged from the 311 respondents who took the time to address the question about the future of the sector. Below I highlight these themes and provide some representative responses, starting out with examples of those who were both optimistic and those less so.

Those “less so” optimistic about the future

This aid worker first starts by making a legitimate point about our survey question in that our wording forced a choice among “significant” “moderate” or “minimal” impact on peoples lives and the inference was that the impact would be some degree of positive. Indeed, that is exactly what I had in mind when writing the question. Here’s what she said:

“Wow. There’s an obvious selection missing above. It is not that far-fetched to suggest that a NEGATIVE impact is the net. When taken in sum, aid policies based on “structural adjustments”, as well as aid dependent on political/military alliances could very well tilt into negative territory, notwithstanding mosquito nets and REMs. Macro aid profoundly affects culture and government. Until aid is withdrawn as a military, political, and cultural weapon, supporting those who swear allegiance to free markets and multinational interests (and then run off with half of the aid money) my bet would be on a grim future for aid as a force for good. Poor nations are crippled by debt while multinationals cart away natural resources and the resulting profits. There will be no net good from aid until it is decoupled. If corruption is endemic to [the country where I now work], the same corruption is endemic to most macro aid.”

This writer clearly embraced a big picture view of the sector. The use of the word “weapon” is particularly sharp and helps make her comment a good articulation of the anti-neoliberal/neocolonial perspective held by many in our sample. Please take a look at this post for more extensive comment about the specific issue of corruption, but in short what is being argued above is that the entire system needs a major -and I think likely impossible- shift in both structure and function of the entire aid industry. In late 2001 when then US Secretary of State Colin Powell called the work of NGO’s a force multiplier he laid bare the fact that the core humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence have in fact been compromised and that the fourth principle of humanity is perhaps additional ‘collateral damage’.

This next post contains many of the same points as the one above and also voices a frequently made distinction between aid and development, with aid for crises having a net positive impact and more long terms efforts being an overall negative.

“I think emergency relief work has the best impact – particularly when responding to an acute crisis in a somewhat stable country where specific expertise and materials are needed to bolster the national response. At the other end is development work in chronically unstable and corrupt countries where I think humanitarian aid work probably does more harm than good and ultimately helps build and solidify a permanent upper class of wealthy elites who pay lip service to the UN while using vaccine money to build themselves swimming pools and send their children to university in Europe.”

This third example voices a frustration with the level of intelligence and adaptability the sector shows.

“Compared to the money being invested, we’re doing a pretty poor job of getting anywhere. A lot of misguided approaches or self-interested approaches or inappropriate interventions or I could go on and on. Why do we know that poverty is not simple or linear, yet still implement interventions as if it is? We need to get better. We need to be smarter, think more critically.”

Critiquing more the HR dimension of the future, this next aid worker voice echoes a theme I have read over and over throughout this research, namely that with regard to expat workers in general there needs to be a better system that takes into account energy levels, family considerations and the big picture issues of knowledge transfer and continuity of efforts. Her comment is a restatement of the one above in that there is a suggestion that we need to “work smarter, not harder.”

“The biggest issue is that they do not get staff into the sector when they are young enough. There should be a push to make vocational way of entering the sector at a younger age to get the “best years” of the staff. i.e. 21-30 when they are more willing to sacrifice their personal lives for their work. Then there needs to be better ways of dealing with staff after 30 when they need a quieter life of their families, but they are often at the peak of their knowledge and what they could contribute to the sector yet seem to begin drifting away from it by then.”

Finally, we have this pessimistic diagnosis “The field is becoming increasingly theoretical and ego-driven. Skills that actually save lives are being drowned out by debates on buzzwords.”

And those who were more positive about the future

Positive and optimistic responses were less common among the 311 responses, and generally came with qualifications. Here are a few examples.

“I think humanitarian aid will have a positive impact on more people because disasters will become more frequent. I think humanitarian aid needs to become much more focused and effective to cope with this, and there are serious obstacles to overcome, but I think humanity will continue to support those in need and humanitarian interventions will keep gradually improving. I think the common perception that humanitarian interventions have not improved over the years is wrong, although the pace of change and the retention of institutional knowledge and learning is poor”.

This first one is referencing disaster relief efforts and says, yes, we’re getting better and just in time because there will be more in the future.

This next one is positive in the sense that it points out a fact of humanity, that there will always be those who want to help. Indeed, properly channeling that energy is the issue since we know very clearly that good intentions are absolutely not always directed in a mindful and progressive manner.

“Humanitarian work will always be needed and always be there as long as there will be man-made and natural disasters. Just its “purity” may be different. It certainly is becoming less pure and self-less, but there will always be people in need and always those wanting to help.”

This next example is perhaps the most optimistic of them all, arguing that the “trajectory is changing.”

“If you asked me 10 years ago, I’d say, ‘cut and run, everyone’, but the trajectory is changing. As I’ve said [numerous] times now, the key is solid evaluation and this is definitely becoming apparent to many organizationss. Also the increasing corporate influence is positive I think – its a tough change for NGOs but it will force them to act more efficiently and think more about results / gain, versus, ‘how do we get more money so we can keep throwing it at things and then produce a glossy pamphlet with this smiling child on it, to get more money’.”

This air worker argues that the sector is improving at least in terms of evaluation and that this is spurned on by corporate influence.

Finally, this one is a counterpoint to the neoliberal critiques and squarely takes sides in the Sachs vs Easterly squabble. Not to rain on anyone’s parade, but what she says below could be seen as innocent.

“I believe the statistics of the impact of aid work can prove that humanity as a whole is improving due to reduced health issues, an increase of education and micro-enterprise enabling people to break out of the cycle of poverty. I think Bill and Melinda Gates really captured this well in their recent annual letter, for instance.”

Is the humanitarian aid sector making positive changes and does the future look bright or bleak? The discussion continues.

Aid is not the same as development

There is a big difference between the relief/disaster response and development work, to be sure, and this difference is highlighted in the responses to the penultimate question on our survey, Q60 “Please use the space below to elaborate on your views about the future of humanitarian aid work.” It is clear to me now that if we had separated out relief/disaster response and development work in our questions the responses may have been even more telling. That said, as I have argued elsewhere on this blog, the binary distinction between relief/disaster response and development is, at best, problematic and ‘pure’ examples of either are likely dramatically outnumbered by those that are a mix.

Here are a couple good examples of how a few aid workers felt about this differentiation.

- “Distinction between humanitarian and development work should be made. Humanitarian [aid] will continue to serve its purpose, especially for those places where the states are unable to provide relief themselves. Development work – I have no clear idea on the impact it has, and whether it’s mostly positive or negative.”

- “There is really no comparing relief and development…”

Marx 101

As a sociologist I was somewhat struck by the number of respondents that expressed an understanding of and a concern about the forces of capitalism that seem to be at play vis-s-vis all things international, especially aid work. As I wrote in the earlier posts, the unfolding algorithm of capitalism is as inexorable as that of biological evolution. But there you go.

- “Humanitarian work is going the way of the dinosaur or jersey’s free of logos … soon enough, it will all be green-washing by some corporation to make themselves or others feel good about how the help people. The end-of-history is starting to subsume humanitarian work; eg., capitalism is dollar-for-dollar far larger than any aid agency, even in the poorest areas.”

- “Probably will go commercialized for profit and things will go much worse. But this isn’t humanitarian aid work – that is business. The non-profit category defines the truth of humanitarian work. All the rest is business – which is also really important, but different.”

For much more on this theme go here.

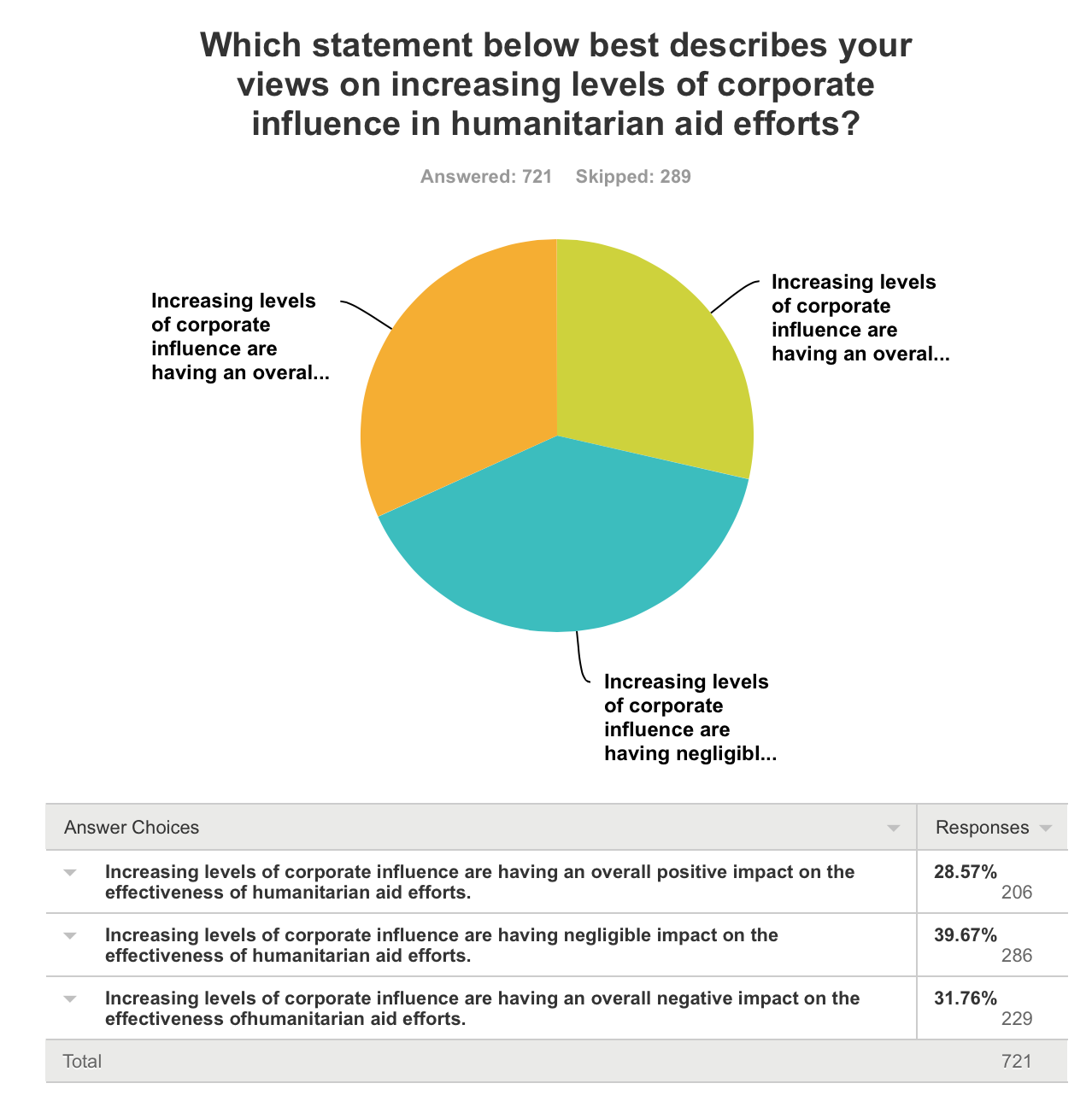

We did ask one question that is somewhat related. As you can see below, there was no agreement on the overall impact on the increasing levels of corporate influence on humanitarian aid efforts, but only 29% of our respondents thought that the overall impact was positive, leaving the remainder, 71% indicating either negligible of even negative overall impact.

Here is a one voice specifically on this topic.

“There will be more participants from corporate or other non traditional actors in HAW in future, the traditional humanitarian sector needs to prepare for this and develop ways of working to ensure that the standards we hold ourselves to are accepted and utilised by other actors. I believe there will always be a need for humanitarian actors with expertise in particular areas, but that these agencies should be comprised of expert staff from the local area – who understand the capacity of local players, government and find a way to amplify what they are capable of doing.”

What this aid worker had to say about increasing corporate (and other non-traditional) influence is critical, I think, as the sector adapts to a changing global environment. That the sector has worked hard to establish core humanitarian standards is progress but unless there is effective messaging about such standards to these external but growing influences the value of this work will not be maximized. Specifically, there needs to be a commonly accepted set of standards for all aid and development work. Getting from where we are to that goal is, indeed, a challenge of significant magnitude.

“There will be more participants from corporate or other non traditional actors in HAW in future, the traditional humanitarian sector needs to prepare for this and develop ways of working to ensure that the standards we hold ourselves to are accepted and utilised by other actors. I believe there will always be a need for humanitarian actors with expertise in particular areas, but that these agencies should be comprised of expert staff from the local area – who understand the capacity of local players, government and find a way to amplify what they are capable of doing.”

The future impact of the sector and what we are learning

Some respondents address the hubris embedded in the assumption that we know what we are doing most of the time. Here’s what one woman said, “We are like the frontier doctors– right now we are “bloodletting” and have no clue how to help people, although we may accidentally have a positive effect. But, our efforts will enable future generations to learn from our mistakes– at least we are doing something!”

Our respondents, I think, on the whole agree with this observation; none would shout from the rafters “We have solved the problems related to delivering aid and development assistance!” Most would say the fact that we are learning is important, but that knowledge transfer both within generations of aid workers and from one generation of workers to the next does not happen as effectively as it should.

Another, also somewhat cynical and summary noted, “I do NOT believe that development work has a longer term positive impact, and I generally do NOT agree with development programmes.”

Professionalizing the sector is important but problematic

That there is more need for further professionalization of the sector is a given. How to get there from here is the big question.

- “I think we need further professionalisation and streamlining, especially for work in increasing numbers of middle income countries. More focus on disaster prevention and mitigation is required.”

- “The professionalization of humanitarian work is/was a good attempt at improving technical competence, but it doesn’t seem to have translated much in improved responses. Lessons learned are not learned. Same incompetent people who responded once will respond again.”

- “It’s going to have to get more professional. Unfortunately I think it will continue to be a desirable line of work, which will see lots of people willing to work for free just to get the chance to work for very little money. I think mistakes will be learnt from the major humanitarian crises and how we respond, but there are always new mistakes to make.”

The comments above compliment those described in my post about aid worker views on smaller “ma and pa” aid organizations, the so-called MONGOs (MyOwnNGO). Stressing adherence to the Core Humanitarian Standards throughout the aid sector is one positive step in this direction.

Some final thoughts on the future of the sector

Some final thoughts on the future of the sector

The future, if we are sober, is murky at best, and the sense that I got from many respondents is that though there will always be need, meeting those needs in a meaningful, efficient manner -both in terms of immediate aid and long term development- is not a certainty.

“I did not like your choices. A key challenge for humanitarian actors is a very narrow donor base (US+N/W Europe) which is vulnerable to budget cuts. We are also entering a new time where most people live in middle income countries, and their governments have greater capacity. In many cases our business model is no longer so relevant. ‘Humanitarian’ work has really ballooned in scope and volume during the last 15 years, in part to get around Paris Declaration-type principles and circumvent host country governments. I think this will have to be scaled back. We are also all very confused what ‘humanitarian’ is – is it defined by the funding source (donor country emergency funding) or is it the type of work (temporary and unplanned)? Much if not most work funded by donors through emergency envelopes is really quite routine and planned, but this modality allows less recipient government scrutiny and coordination – for better or worse.”

What can be concluded from the above and my previous two posts (here and here) regarding what aid workers thought about the future? Said one,

“For better or worse, aid work needs to continue. Self assessment in the sector, like this survey and other data sharing and transparency measures, need to continue and expand. This is especially true for funders making decisions on programming that may or may not address the real demands and needs.”

Aid workers are a thoughtful bunch who care deeply about what they do and the larger context within which they function, at least those who took the time to respond to our survey certainly seem that way to me. Whether or not one believes there is hope for the future with regard to aid and development work depends upon perspective and level of sobriety, methinks.

depends upon perspective and level of sobriety, methinks.

Pass the Barbancourt, please.

As always, please contact me with questions or comments. @tarcaro on Twitter.

Follow

Follow