See 29 December 2020 update on this post here.

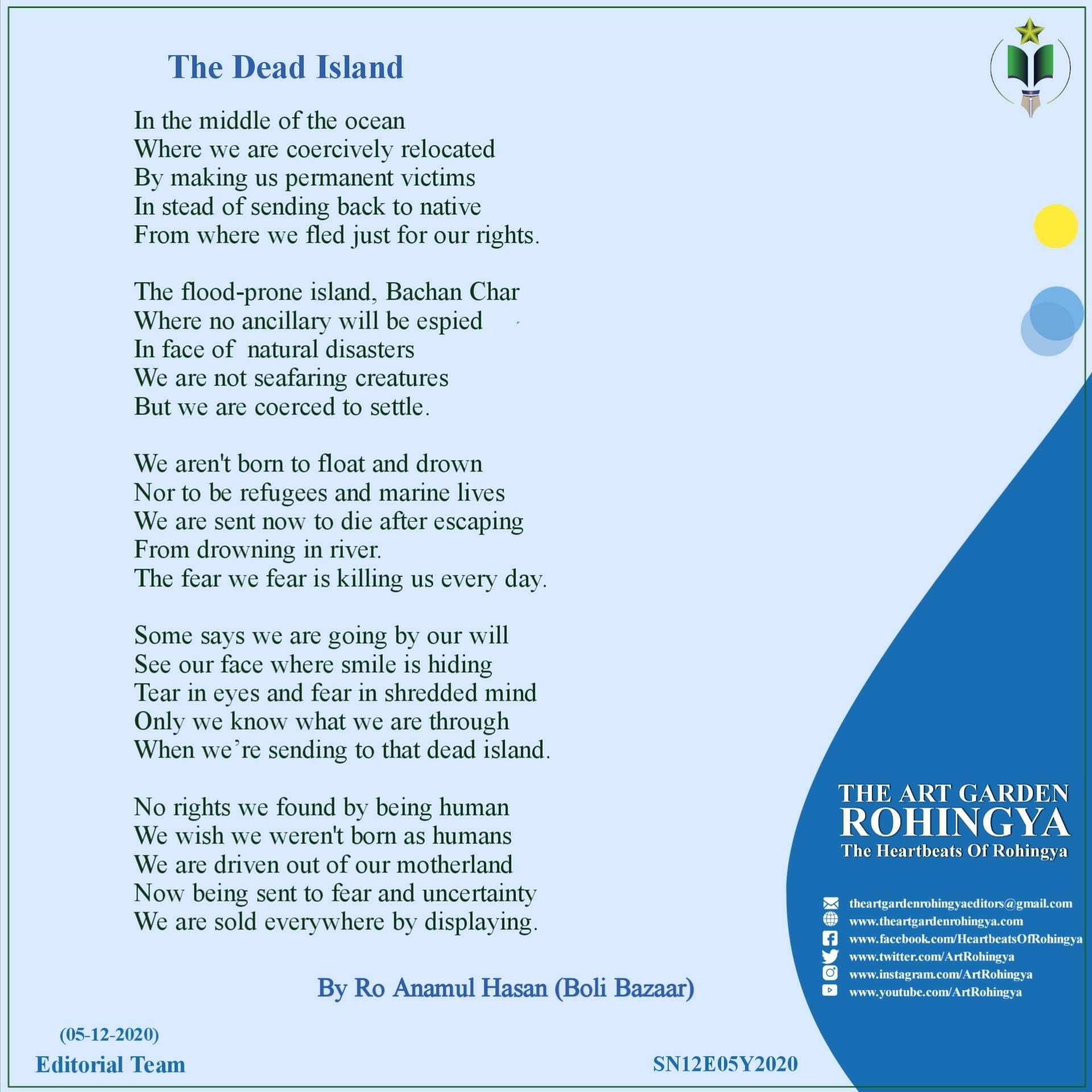

“We aren’t born to float and drown/Nor to be refugees …”

-Ro Anamul Hasan, from his poem The Dead Island

Humanitarian questions about the relocation of Rohingya to Bhashan Char Island

In their own words

This report by Amnesty International, LET US SPEAK FOR OUR RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF ROHINGYA REFUGEES IN BANGLADESH provides an excellent and up to date overview of the plight facing the Rohingya. In eight sections using first person accounts from Rohingya, both women and men tell detailed and compelling stories. The section titled “This is worse than prison” gives the accounts of Rohingya who were brought to Bhashan Char in May, 2020 having been turned away by Malaysian authorities after a traumatic months long sea journey. The title of this section (“This is worse than prison”) summarizes the feelings of those already on the Bhashan Char and foreshadows what is to come for the Rohingya who arrived on the island recently.

The Move to Bhashan Char Island

The Bangladeshi government’s plan to move Rohingya refugees to Bhashan Char Island has been unfolding for several years now. Just in the last several days boatloads of families have been moved from the sprawling refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar to this new island in the Bay of Bengal. The ultimate goal is to move 100,000 or more Rohingya to this ‘made to order’ refugee camp. See here for a detailed visual history of the island.

On Friday, December 3rd, seven Bangladeshi naval boats transported more than 1,640 Rohingya refugees to Bhashan Char. There is an expectation that many more boatloads are to follow in the coming weeks and months.

The future of those who are moved to Bhashan Char seems as tenuous as that of the island itself. The Rohingya goal of repatriation with full citizenship rights to their former villages in Myanmar seems not reachable given the current political situation and lack of effective pressure from the international community. Despite international pressure, the Rohingya remain unrecognized by the Myanmar government, who prefers to use the pejorative term ‘Bengali’ to refer to this ethnic group which has lived in Burma/Myanmar for many centuries. Once on Bhashan Char, no one knows what will happen either to the refugees or the island itself, especially in the coming monsoon and cyclone seasons.

A ‘char’ is by definition an unstable, shifting island, with Bhashan Char (literally ‘floating island’) emerging from the Bay of Bengal just 14 years ago, changing in size and shape as the years pass. Construction on the island began in March of 2017 with the building of a helipad.

In quick succession, roads were created and land cleared for what is now a large cluster of buildings. The Chinese construction company Sinohydro completed an 8 mile (13km) flood-defense embankment surrounding the encampment, and the 1440 closely packed red roof buildings cover several acres. Each building has communal toilets on one end, shared kitchen space on the opposite end, and sixteen 12×14 feet (3.7 x 4.3 m) shelters providing approximately 3.6 square meters in covered living area per person, just above the UN requirement of 3.5 square meters per person for emergency shelters.1

Resistance to the move

Resistance to the decision to relocate Rohingya refugees to Bhashan Char has been widespread, coming from Rohingya activists, human rights organizations, and the UN. The UN has maintained that those being relocated should be doing so by their own informed choice, but it appears that UN representatives have not been allowed access to the process by which families were chosen for relocation.

Reaction from the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar has taken many forms, and tension in the camps is high both because of the recent movement to the island and due to worsening corruption and violence within the camps, much of which is related to actions taken by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). There is some speculation that the two events may be related.

Reaction from the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar has taken many forms, and tension in the camps is high both because of the recent movement to the island and due to worsening corruption and violence within the camps, much of which is related to actions taken by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). There is some speculation that the two events may be related.

In a recent online conversation with one Rohingya I was told,

“They [the families that chose to relocate] were badly persecuted by the members of ARSA for no specific reason and their minds were changed to move from the camp to their secure lives. Also the government of Bangladesh gave 5000 taka per person [approx. $60USD] to those who chose to move to the island.”

Commenting on the situation from a more general perspective another young Rohingya said,

“For days now there has been continuous reporting on the fate of the Rohingya and I’m slowly wondering that what deeper meaning is behind it? Should the Burma be prepared so that the federal [Myanmar] government might already have the great idea of wanting to accept Rohingya for humanitarian reasons?”

I have been fortunate to communicate with and write about many Rohingya who express themselves through poetry. Please read above the work “The Dead Island” by my collaborator and poet Ro Anamul Hasan. His words capture the confusion, anger, angst, and the frustrating feeling of hopelessness that can dominate the minds of even the most resilient and articulate refugees. He says, in part, “We are driven out of our homeland/Now being sent to fear and uncertainty.” There is little mystery why relocation to Bhashan Char is controversial within the Rohingya community.

A humanitarian crisis

The issues in Cox’s Bazar are many and all add up to a massive, chronic, and purely human-made humanitarian crisis. Those working for the UN and other humanitarian INGOs based in Cox’s Bazar face a challenging situation. Staff from IOM, DRC, MSF and others must balance realities of local and national Bangladeshi politics with the needs of the Rohingya refugees who exist as guests in a nation not their own but feel they are treated as prisoners. The

social and cultural realities of camp life include, sadly, all of the social ills that beset all cultures across the globe: drug abuse, gangs, corruption, SGBV, and, insult upon insult, the spread of COVID-19 within the camps. And now humanitarians and the refugees themselves must handle this additional stressor -the tension around who will be relocated to Bhashan Char. That the Bangladeshi government has not fully involved the UN and other organizations is a clear point of stress.

Bangladesh, a densely populated and poor nation, has had to absorb Rohingya refugees for decades, with a huge flood coming in the wake of genocidal actions by the Myanmar government and military in August 2017. Their way forward includes exploring all options, and when Bhashan Char emerged from the sea, easing the crowding in Cox’s Bazar through relocation of Rohingya refugees presented an additional, albeit controversial, option.

A better life?

I wonder what stories will come from Bhashan Char now that the first big wave of Rohingya have been resettled to this ‘floating island’. And then I ask, who will listen to these stories and what will come of what is learned? On a personal level I question my efforts to amplify the Rohingya voices I hear over FaceBook and WhatsApp. At the end of the day I am left with few answers. Will those relocated have a better life on Bhashan Char, and compared to what?

There are two things in which I do have firm confidence. First, the humanitarians working in Cox’s Bazar will give full measure each day as they do their jobs, and that organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Fortify Rights will continue their advocacy of the Rohingya. Secondly, I have faith that the many Rohingya who work daily in the camps to create a better life for themselves and their community will not waver in their efforts and will continue to meet every challenge.

If you have questions, comments, or feedback you can contact me at arcaro@elon.edu.

- All information based on Reuters web site accessed 5 December 2020.

Follow

Follow