“Don’t believe this should be long career.”

-female expat aid worker

“I think that the aid sector would ultimately benefit from a HR base that has a wider variety of experiences. I don’t think staying in the sector my whole career is healthy for the sector or for my intellectual development.”

-male HQ aid worker

“I feel that I will always be connected to this line of work in one way or another. If it is not working internationally as an ex pat, then I will most likely be working locally for various NGOs in my home country or city. If not that, then I see myself pursuing a PhD where the topic of research will be related to humanitarian work.”

-female expat aid worker

Why do aid workers leave this line of work?

Overview

In my last post you read many aid worker voices about the topic of getting fired. As we learned from the data, the perception is that getting fired in the literal sense happens very infrequently and getting “let go” -as in not having a contract renewed- is more common. That said, the humanitarian aid and development sector has a fluid work force, in general, and staff come and go for all manner of reasons.

Our survey included four questions attempting to drill down into what these reasons might be.

In Q44 we asked “Many (most?) humanitarian aid workers will ultimately become ex-humanitarian aid workers. Which below do you think is the *most* common reason why humanitarian aid workers choose to leave this line of work?” and then in Q45 we followed up with an open ended question asking the respondent to give their thoughts as to “why humanitarian aid workers will ultimately become ex-humanitarian aid workers.”

Q46 was a forced choice format asking “Many (most?) humanitarian aid workers will ultimately become ex-humanitarian aid workers. Excluding the unlikely and tragic possibility that you will die in service, if you do so by choice which below do you think will be *your* reason for leaving this line of work?” and the results are below. In an additional follow up question Q47 we asked “Please use this space to elaborate on your answer to the above question asking about your reason for leaving this line of work?”

Here again (this was included in the last post) are the data for Q44. Given that the respondents represent varying levels of longevity on the industry, many with just a few years, the responses below are based mostly on impressions. The forced choice responses we offered are not necessarily mutually exclusive and so the qualitative data from the follow up questions yields our best source for the ‘real’ reasons people might leave the sector. Analysis and comment on the two open ended questions is below.

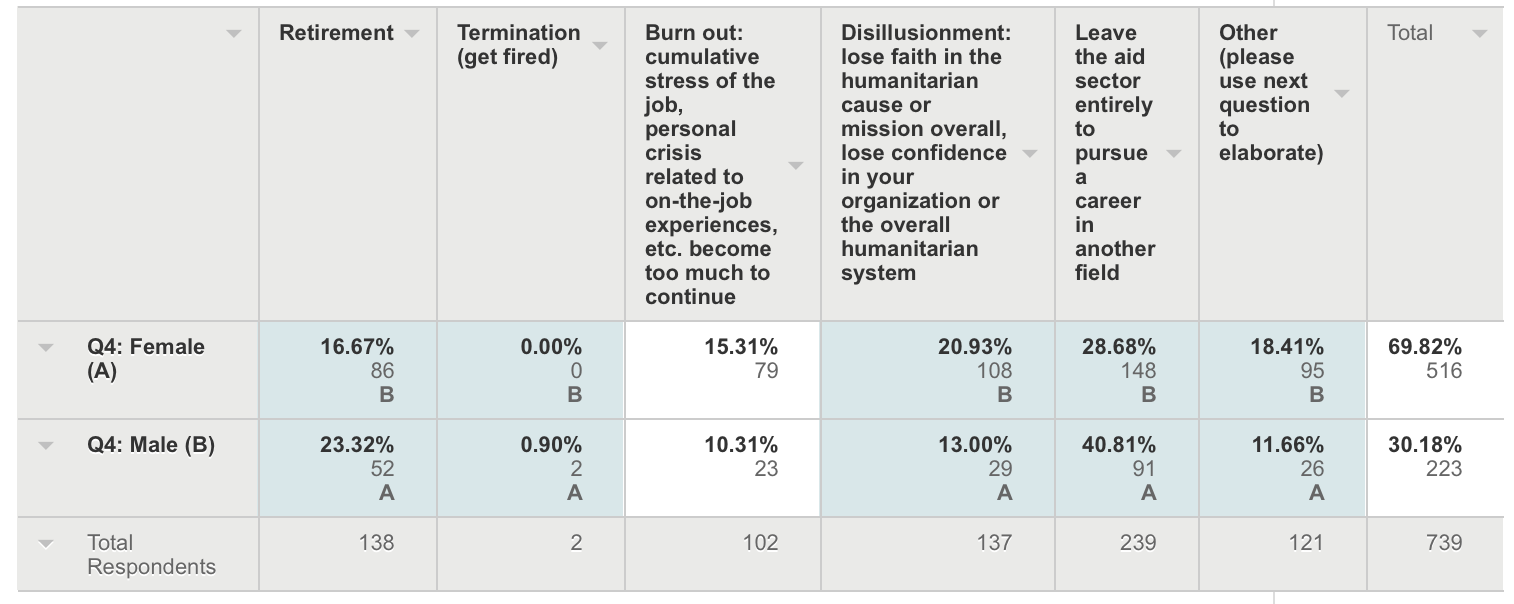

Data from Q46 -“Many (most?) humanitarian aid workers will ultimately become ex-humanitarian aid workers. Excluding the unlikely and tragic possibility that you will die in service, if you do so by choice which below do you think will be *your* reason for leaving this line of work?”- below are presented in a table format to emphasize the difference between those that identified as male as compared top those identifying as female. As you can see, the same forced choices were used but now, breaking down for gender, we see something interesting. Those numbers in pale blue indicate statistical significance, and five of the six choices fall into this category, raising the question about why female aid workers feel differently about why they or others might eventually leave the sector. We can discount the “Termination (get fired)” answer, but the others are worth a look. In words, here is what we see below:

- Males are significantly more likely to see themselves as ‘lifers’, retiring as aid workers.

- Females are significantly more likely to think they’ll leave because of “disillusionment’ of some sort.

- Males are significantly more likely to think they will leave to pursue another career outside the sector.

- Females are significantly more likely to indicate they have “other reasons”.

That’s the ‘what’. The ‘why’ lies within the narrative responses.

Thoughtful responses related to disillusionment

Many key points are made by the four respondents below perhaps the most important of which is the generalization -borne out by the responses to Q31 (discussed here)- that a majority of people enter and stay in the sector for humanitarian-related reasons; they care about others. When the choice to leave the sector is considered, the reason is not that they no longer care but rather that life priorities have altered. Many feel that they can live out their impulse to make a difference in other ways.

The second comment makes an interesting point about career trajectories. She makes an argument with which I do not disagree, namely that the sector can be inherently frustrating for many reasons, one of which is the incompetence or lack of compassion by those in high-level position. Several additional key reasons include (1) the gap between what needs to be accomplished and what is accomplished is often pretty wide, and the understanding of that gap gets clearer the longer one stays in the sector, (2) massive, large scale change is impossible through the sector alone; macro level economic and political change must come first, and (3) though more related to development work than to aid work, there is a creeping sense that the very raison ‘d etre of the industry may be flawed and that, writ large, effective and sustainable change can only come from within.

The second comment makes an interesting point about career trajectories. She makes an argument with which I do not disagree, namely that the sector can be inherently frustrating for many reasons, one of which is the incompetence or lack of compassion by those in high-level position. Several additional key reasons include (1) the gap between what needs to be accomplished and what is accomplished is often pretty wide, and the understanding of that gap gets clearer the longer one stays in the sector, (2) massive, large scale change is impossible through the sector alone; macro level economic and political change must come first, and (3) though more related to development work than to aid work, there is a creeping sense that the very raison ‘d etre of the industry may be flawed and that, writ large, effective and sustainable change can only come from within.

Listen to these voices.

As to why she might leave the sector this woman speaks of the disillusionment with her situation and by inference perhaps the entire sector, affirming my point above.

“For myself it will be the risk and the growing appreciation that change must come from within, working recently in South Sudan I realised the fragility of the human condition and how ultimately pointless all this development is if the conditions and structures are not in place to maintain peace from the grassroots.”

This next woman reflects along the same line though even more cynical.

“It is questionable if we are doing any good, a lot of what we do as expats could be better done by local staff. We take a lot of money out of local economies and distort them with how much we are willing to pay for goods and services. In places like Cambodia, I question if we are doing more good than harm.”

Next an honest, insightful big picture look at the issue.

“This is a sector filled with people who need to believe in their work and believe that they are accomplishing something (not necessarily “saving the world”, but at least doing something productive and that they feel is worthwhile). by nature, i think this is therefore a group more prone to disillusionment than other others (bankers, lawyers, whatever). no doubt, the aid world is deeply flawed, but people working in fields where they don’t need so badly to believe their work is worthwhile and being done well are less likely to get fed up and leave. as well-intentioned, experienced aid workers get too frustrated/burnt out to remain in their chosen career, it also means that a lot of the people who stay and move up the management chain are those who either don’t care about the problems or aren’t willing to address them because they have too much to lose. this creates further disillusionment with people who want to do their jobs well. burn-out is certainly also an issue, but there are an awful lot of burnt-out aid workers who keep working in aid whether or not it’s good for them or anyone else.”

And now this one, even more personal.

“I think it’s often a combination of many things and i can see this coming for myself – wanting more stability, being soul-tired of being ‘foreign’, being tired of the same conversations, over and over (all those ‘lessons learned’ being left in a folder on a shelf somewhere), needing to earn more money, not  wanting to be old in the field, wanting more balance in life so that work is not so all-consuming, becoming more cynical. More positively, one of the things that i love about this work is that everyone has dreams and ideas about what else they would like to do – usually it’s still something connected to making the world a better place, but i love that no-one thinks this is it and there aren’t other possibilities as well, one day. I don’t see this in non-humanitarian industries – it tends to be a rare and notable thing when people retrain and do something different and i love it that we generally have other ideas too.”

wanting to be old in the field, wanting more balance in life so that work is not so all-consuming, becoming more cynical. More positively, one of the things that i love about this work is that everyone has dreams and ideas about what else they would like to do – usually it’s still something connected to making the world a better place, but i love that no-one thinks this is it and there aren’t other possibilities as well, one day. I don’t see this in non-humanitarian industries – it tends to be a rare and notable thing when people retrain and do something different and i love it that we generally have other ideas too.”

Where to if not the aid sector?

Over and over again in the hundreds of written responses I found statements affirming that aid workers are “different” as a group and that they do want to live what they consider to be meaningful and humanitarian-focused lives, many sounding like this woman, “And transition into domestic social justice work.”

Many permutations of this same sentiment came out in the data, some offering the thought that they could remain positive agents of social change near home and others indicating that the sector was shifting in ways that would take them home regardless. Here are a few that voice a sense that the sector may be changing toward the private sector.

- “I think the humanitarian sector is valuable and needed but I also think private sector will ultimately be the catalyst of growth.”

- “CSR is the way forward.”

- “I think I will always be involved in development, one way or the other. Development isn’t only about working for an NGO, but can come from private sector or other means.”

Aid workers, like workers in any industry, regularly at least consider career moves as a matter of course; we all think ahead to the ‘next step.’ To what extent is this sector different than others? Perhaps some clues can be found below.

Family and relationships a big factor

Many -both males and females- gave relationship related reasons why they will leave the sector. This first one from a female expat speaks, I think for many.

“Eventually i will want to have a dog, and i’ll have to pursue a more conventional job in my home country for this. also, my partner will want to go home.”

Here are a few more representing this general sentiment, the last I feel confident will resonate with many females.

- “In order to start a family of my own and to be closer to support my aging parents.”

- “It would probably be for family reason and i will pursue another job that fits better the needs of my family.”

- ” [I] will want to settle and have children at some point and also do not want to become one of the insane and bitter people who have spent too long in the field!”

- “If I continue to get told that having a child is difficult in finding positions other than HQ I will quit trying at some point. Idealism doesnt put food on the table.”

- “I don’t know yet, but this game isn’t much one for settling down and having a family. As chicks, we get to a certain age where the biological clock ticks pretty loudly and we have to weigh up our options of a steady job or moving on. We shall see.”

- “I want to actually live in the same city as my husband for a few years before we have kids… his line of work doesn’t exactly bring him to conflict-affected areas.”

- “I’ve got a partner and dreams of seeing a garden through an entire season; it’s hard to imagine getting lucky enough to get a secure enough aid job that I can also have a stable home life in my city of choice. This is one of the “second wave feminist” Lean In problems, but I hate to say I am totally facing it.”

Finally, continuing the feminist note, this woman felt the need to end her note demonstratively.

“If you are a woman, you often have to leave to have a family. the humanitarian and emergency sector is entirely unforgiving to those (especially women) who choose to have kids. accompanied missions are hard to come by, you dont get them in tough places, and the work hours and travel needed prohibit family life. a woman can be a mother but she has to choose a different kind of job (i.e. a desk job in HQ) or if lucky an accompanied mission. OR she leaves. I am very lucky to currently have a stable job in an accompanied position working on humanaitarian projects. This allowed me to have a baby. However, I am under NO illusion that my career prospects have considerably narrowed, and i will have to fight for the next accompanied mission. Or just give it up. Although I am flexible and do travel away from my family for some time, I refuse to choose a job that another aid worker can do, in place of my child. Its a young persons game, or a single persons game, and for the reason above, in the long term, it tends to be a MANS game.”

Now for some other themes from the data.

Money and career options

These next few reflect numerous themes in the data, though I include them specifically to represent the mention of low pay that was echoed by many.

“I guess I hope I find a balance in life. I think Aid work is not the end all. It doesn’t pay enough, and there are people close to home that need help as well. And then there is family and friends. Finally Aid work is evolving and the line between the private sector and development is changing. I would like to think I will evolve as well and find a place where my skills and experience can be used before I get shot or burn out.”

“Money is a big concern. I spent most of my 20’s making less than half of what my college friends are making doing non-aid work. If I am interested in having a family, this will be a big issue for me. I have already begun looking at options in management consulting and defense contracting… no reason but money to do those things, but I’m not sure how I could transition to any other fields at this point.”

“I am interested mainly in marketing and PR which is what I’m currently doing for my organisation. But if a more interesting or lucrative opportunity were to arise in another field, I would probably take it.”

“I am interested mainly in marketing and PR which is what I’m currently doing for my organisation. But if a more interesting or lucrative opportunity were to arise in another field, I would probably take it.”

The mention above that “the line between the private sector and development is changing” is interesting and reflects a good bit what I presented in this post discussing aid workers views on the future of humanitarian aid.

The wear and tear on body and soul of being an (expat) aid worker

Some jobs in the sector -maybe most?- take a heavy toll, and that toll is tolerated by many for long periods of time, I conjecture, because most view this array of experiences and emotions as ‘#firstworldproblems’ and just make an effort to just ‘suck it up.’ But these efforts can fail over time and eventually lead to considering a career change.

“I am so fucking tired of the constant heckling, jeering, staring, groping, and living in fear. Every day I experience a moment during which I could easily die. I’m incredibly isolated. I’m unhealthy. I’m ready to be happy and healthy and surrounded by people who love me in a place where I fit in.”

“Having already experienced burnout in this field, I”m carefully on watch for it happening again and working against that. If it every starts to head down that path again, I will leave. I will not compromise myself or those close to me in such a way again.”

“Wanting to have light 24 hours a day, safe clean water, no need to have house security measures, good health services, usage of functional public transport, fully stocked Supermarkets and just being one more person on the street, not having the “Expat” label on my back.”

Not even imagining a career change.

Though the prompt asked respondents to image what might lead them to become “ex-humanitarian aid workers” many were not ready to even consider this option. The responses below indicate the range of reasons.

- “I love everything about this job (I am 28 and single!) and I suspect over the years the nature of work will change but I will stay in this sector.”

- “I like my line of work, I like change every few years, my family is on board and we enjoy this (privileged) lifestyle. We find the schools are superior than those at home (except for the ones we’d have to pay through the nose for). We enjoy the travel, meeting other cultures, living in amazing places…instead of visiting them for just a week.”

- “Can’t see myself back in a normal job, or back living in the West. Lack of money is not a problem – mostly.”

- “I would hope to make it to retirement but am not so unrealistic to think I can keeping working like this for another 20 years. Will probably negotiate a job at headquarters with limited travel in the next 5-10 years and hope the pension matures to something that will keep me warm and fed anytime thereafter.”

Concluding thoughts?

I continue to be struck at the forthrightness and thoughtfulness represented in what aid workers wrote. Here are a few to end this section, each waxing philosophical on the nature of the their lives and work.

“I have already pretty much lost faith in the humanitarian system, and don’t feel ethically good accepting most of the job opportunities available to me. They mostly seem like they may potentially put me in a situation where I would have to exploit a community for the sake of a donor, and I am just not ok

with that and don’t even want to be put in the position to do such a thing. So I may have to look for a job in another field where I can make my money with less moral ambiguity and then do my own ‘development work’ on my own time and my own dime.”

“Even though I say I am pragmatic, I am also increasingly weary and just disappointed in our industry for not being *better*. I am more often disappointed these days than inspired and think our industry is on a path toward self-destruction if we don’t get our acts together. There are many more players today who want “in” on the development project, and we stodgy INGOs seem to resent that we don’t have a corner on the market anymore. I think the age of the “big INGO” is increasingly going to be challenged by actors that are younger, bolder, more nimble and lean, innovative, etc., and at some point I will probably want to jump ship rather than go down with it.”

This next one points to the fact that many aid workers are in relationships and career choices are negotiated dance with partners, family and so on.

“I do think people face a personal crisis or moment of choice, career wise or life-wise. For me I think what I like about the job (living new places, working for an organization I – with some caveats, but fundamentally – believe in) can be achieved in not-humanitarian work, more general development work and the like. I want to keep living abroad and working for international institutions, maybe that means more humanitarian work, maybe it means something else. I have a partner with the same goals, which helps a lot – but it also means maybe my choices will be dictated by his next job.”

Yeah, one’s journey through life is complicated and impacts by many forces, some under our control and others not so much. That the aid worker’s journey may life trajectory is more complicated than some seems to be too be very apparent from the voices reported above.

As always, please contact me with questions or comments.

Follow

Follow