You’re fired! Not a phrase heard often in the sector

“We do need to become more effective and efficient at what we do…. and get better at firing well-meaning people who are not competent at their work….”

— male HQ worker

“Ha ha. I work for the UN. Nobody gets fired.”

–not-to-be-identified respondent

“I have worked with too many colleagues – senior managers included – who were not qualified for the jobs they were hired to do. I wish the development and aid industry would take on a more private sector approach when staff clearly are not performing in their jobs – despite coaching, training, investment etc. It makes me angry that public funds from taxpayers or donors are wasted.”

— female local aid worker

“Fired? Really? Does this happen? I wish more would be fired, the incompetence in this sector is one of the reasons I will probably lose confidence in the system.”

— female HQ worker

“My position does allow me a line of sight to the HR processes in some of the terminations at my org. All of those reasons explain why people I know of were fired: those that were promoted too high too fast and aren’t competent in their current roles are often “downsized”, those who chronically bump heads with their superiors are often “downsized” (whether personality clashes or differences of philosophy), and I’ve seen an (otherwise) good employee drive drunk once using the company vehicle (and then lie about it!) “resign” in the middle of the investigation. In my org, at least, many more employees are “downsized” or during a “restructure” their job description changes, and they’re asked to reapply and don’t get it. Not too many are outright fired (due to legal liability that would open us up to). Others simply don’t have their contracts renewed when they expire.”

–not-to-be-identified respondent

Where we’re headed

Below I both present more data -mostly qualitative- and also offer some analysis, comment and opinion regarding getting fired -or not- in the aid worker world. First, validating the title of this posts, here’s what our respondents noted in Q44. That tiny slice of the pie chart below represents the .52% -less than one percent- getting fired. [Note: I’ll look at the other reasons mentioned below elsewhere on this blog.]

Some thoughts on the ‘big picture’

Gross generalization: this sector’s work-force profile is the way it is because of the nature of the work and the unique -and recent- exponential growth in both the size the number of aid entities in the last 20 years.

For present purposes we can go with the most basic taxonomy: there for-profit and not-for-profit organizational entities. In general, in the for-profit sector there is very little patience for incompetence and, given chronically high under and unemployment factors, -that is, it is a buyers market- it is understood that lack of performance will get you fired. The bottom line is the bottom line. An important related factor is that measuring output/performance is, at base, very simple in the for-profit world; again, the bottom line is the bottom line.

In direct relation to the difficulty of  quantifying performance -measuring with some fidelity the value-added of someone’s activities on the job- the nature of the firing process gets more complicated.

quantifying performance -measuring with some fidelity the value-added of someone’s activities on the job- the nature of the firing process gets more complicated.

In the non-profit world the deliverables tend to be inherently more nuanced, difficult to quantify and frequently are, and are intended to be, long term results. Yes, some tasks are easier than others onto which attach metrics, but there are so many tasks the outcome of which is (1) long term/beyond the contract period of the worker, (2) interconnected with myriad other factors that make it difficult to discern clear linear cause-and-effect impact, and (3) are part of a team effort that make individual contribution hard to parse out.

The not-for-profit world includes many organizations such as in the humanitarian aid world but also, for example, higher education. As an academic I am keenly aware of the promotion and tenure process and know well the battles that are fought over what “counts” toward same. Indeed, in my world, unfortunately, not being able to make that which is real measurable we tend to make that which is measurable real. Translation: publish or perish because you can’t measure service and “good teaching.”

The nature of the humanitarian aid world

There will always be those who feel they belong in the humanitarian aid world in whatever role because they feel compelled to “help”. I stand by my assertion that this is a basic human need; we are wired to feel empathy (mirror neurons, anyone?). As one respondent put it, “There will always be disasters, there will always be poverty and there will always be some people who feel impelled to try and make a difference.”

Given the questions we asked there is no way to tell if our respondents associated with at any specific aid organization -with the major exception knowing that 6.5% of our respondents work “somewhere in the UN System”- but my guess is that very few if any were with MSF. The MSF reputation in the aid world was clearly elevated -and affirmed?- in 1999 when they received the Nobel Peace Prize, and my sense is that though they coordinate with other organizations on important matters (e..g., cluster meetings) there is a clear demarcation between “us” and other aid organizations. On a smaller scale, in Haiti Partners in Health might be seen in a similar light.

The reason I am pointing this out is that I believe that what these two organizations have established is what the rest of the industry appears to lack, namely higher than typical entry and renewal standards for all associates. These two, MSF and PIH, are outliers in that both are medical and health-focused niche agencies. They’ve focused on specific sectors (medicine, community health) that are quite technical and for which the standards of qualification are well-established and globally regulated, and so firing someone for incompetence (malpractice in the medical world) would be relatively straightforward for both. That said, management of HR is not without its challenges, as they have significant turnover rates as well. That a look here for specific research comment on this topic.

There is a non-existent -or at the very best, weak culture of firing in the sector within many organizations. As evidenced by our respondents comments, that this should change is without question. But how do you create and sustain a “culture of firing?” Perhaps you start at the source of the problem. Organizations are systems, and systems can only function as well as their weakest component. As one aid industry insider put it, “fear of adverse public opinion drives ass-covering HR policy and process.”

Reasons why people do not get fired

A reading of all the narrative responses yields the following observations. People do not get fired because (1) a warm body that can function minimally is better than an empty desk; something is better than nothing (“Lots of people think their very presence is valuable, because poor people need all the help they can get or something.”, (2) metrics for performance are unclear and hard to measure, (3) it is much easier to just let a contract run out and not renew, i.e., passive firing (said one respondent, “Honestly, it can be hard to be fired. Many people simply don’t have their contracts renewed.”), and (4) the firing process can be time consuming and, ultimately, more trouble than it is worth for the supervisor. Another reason suggested by a long-time industry insider is the extreme risk-averse nature of NGOs, especially established household charities is the underlying cause of so much: they’re very afraid of litigation, especially litigation that gets dragged out into the public, paints them in a poor light, and costs them donors. The necessity of kowtowing to the needs and expectations of donors is indeed a common frustration among aid workers.

Some data

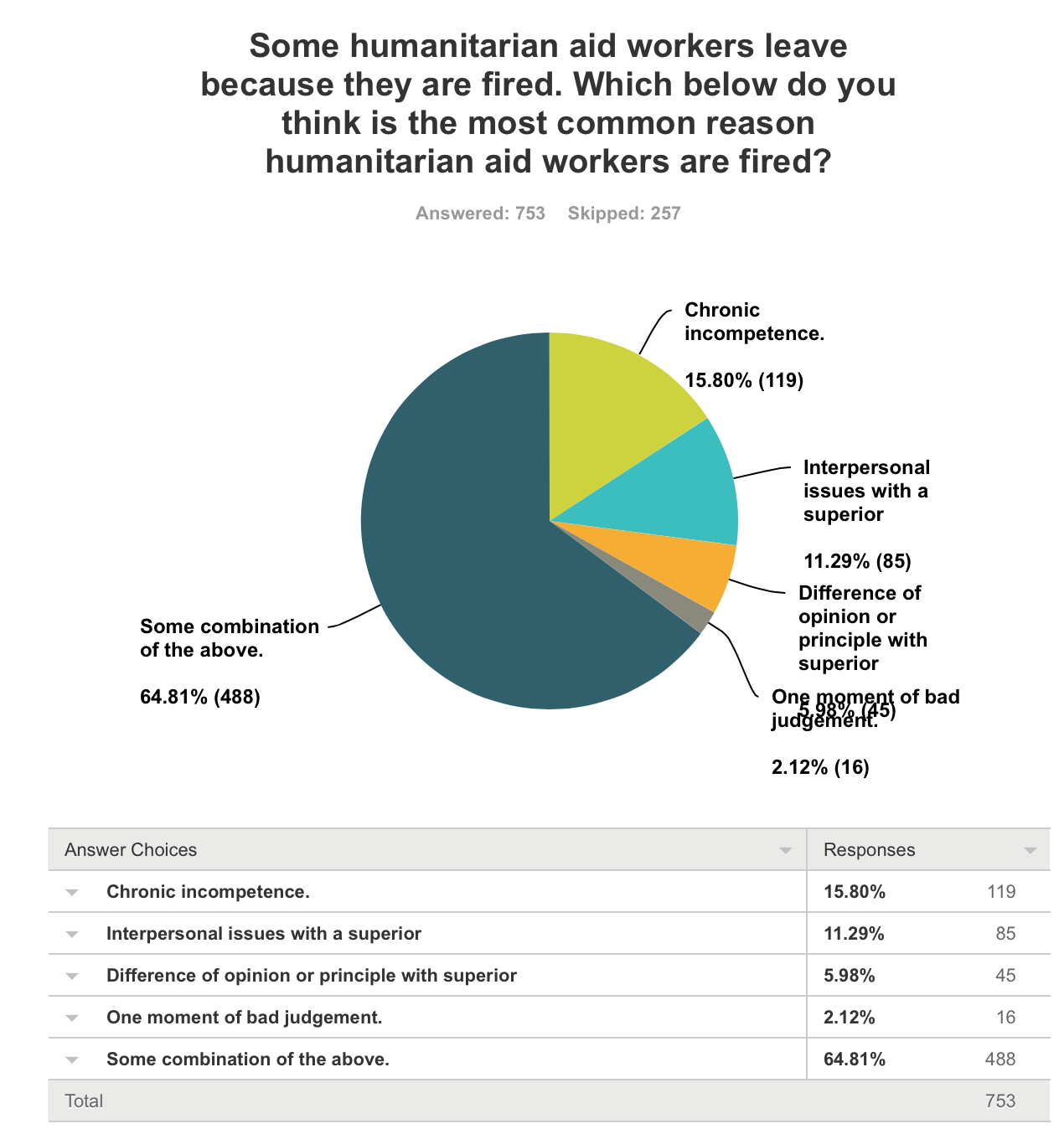

Q48 asked “Some humanitarian aid workers leave because they are fired. Which below do you think is the most common reason humanitarian aid workers are fired?” Here are the data:

Reasons for firing someone are rarely simple. That 65% of the respondents answered “Some combination of the above” seems logical and telling. Though our survey respondents guessed that less than 1% of people leave the sector because they are fired, I find it interesting that 366 respondents took there time to offer narrative thoughts on Q49 “Please use the space below to elaborate on the question above concerning what you think is the most common reason humanitarian aid workers are fired? Most, though, did use that space to vent about why people were not fired.

Aid worker voices on (the lack of) firing in the aid sector

A robust number of respondents -372- chose to complete the open-ended question Q49: “Please use the space below to elaborate on the question above concerning what you think is the most common reason humanitarian aid workers are fired?” Here are some of their responses, most illustrating the reasons I listed above.

This first one hits on a dominant theme in the responses, namely that the structure of the sector can make personnel issues complicated and easy to ignore and/or deal with ineffectively.

“I don’t think nearly enough aid workers get fired for chronic incompetence. If it was up to me there’d be more of it. The problem with people on 3, 6, 12 month contracts is people are too busy / not good enough at management to performance appraise, and tend to just let people’s contracts lapse, or let them move on – no one reference checks properly, or does informal checks, and it means genuinely dreadful aid workers get employed again and again. This does real damage to the NGO sector. The UN is probably worse by the experience I have had of those agencies – so well paid, and benefits so good that complacent, disenfranchised people stay in jobs otherwise their kids would have to come out of boarding school/they’d have to give up that holiday house and the enormous DSRs. It’s dispiriting. I’m sorry if that doesnt quite answer your question, but I have not really seen many people fired. The only one was a bad judgement on security brought on by incompetence and inexperience. Sometimes also people are promoted way too quickly and lack any depth of knowledge on a context which can lead to some very naive decision making.” –female expat aid worker

The several responses below point to a major theme, namely that there is (a perception of) a great deal of incompetence in the sector, and it is tolerated or at least not dealt with head on.

- “Incompetence generally doesn’t get people fired on its own (not unless it results in some really major fuck up), but incompetence coupled with interpersonal issues with a superior is definitely going to put someone at real risk of losing their job. Interpersonal issues really come to prominence in shared housing.” female expat aid worker

- “Unfortunately, incompetence is more rarely the cause of losing your job as a humanitarian worker, than politics around principles, opinions or personality differences within the team (not necessarily a superior).” female expat aid worker

- Chronic incompetence is the least likely reason….” male HQ aid worker

- “I think it’s incredibly difficult to fire people in this field and most who are fired are for issues to do with supervisors. Not incompetence. That’s usually encouraged or promoted (seriously..).” female

- “Honestly, not enough aid workers are fired. I have seen seriously incompetent workers go from one agency to another because apparently nobody EVER gives a bad reference – even if a guy is a barely functioning alcoholic that regularly uses prostitutes and goes around in the NGO t-shirt!”

- “Man, if people got fired from humanitarian aid jobs because of chronic incompetence, the industry would be a better place. I think most people get fired out of a combination of interpersonal issues with superiors or funders, combined with a sense that they’re not quite what the organization needs.” male in regional office

- “It really has to be chronic, chronic incompetence as the sector seems to recycle poorly performing workers all the time.” non-white female expat aid worker

- “Incompetence plagues this sector. Many people get jobs through personal connections with little or no relevant experience. Training is generally poor and opportunities to learn come from other people with academic and developing world experience only. We need more people transitioning from senior private sector roles ideally to up-skill the development labour force.” female expat aid worker

These next two highlight the perception that even when the situation calls for it, firing just does not happen.

“Unfortunately, it is not for reasons for which firing should occur (eg. sexual misconduct, abuse of minors, fraud) but for failing to successfully navigate relationships with a boss. I have never been fired, by the way, but seen many occasions where it unjustly occurred, or unjustly did not occur.” female expat aid worker

“I would guess that the most common reasons would be interpersonal issues and a difference of opinion. Aid workers have strong personalities and strong opinions…and sometimes superiors have plenty of pride. A moment of bad judgement could also lead to being fired.” female expat aid worker

This next one points to an issue about lateral moves after being fired. Why this happens is a critical question.

“The question is whether the fired get re-hired in the industry. Which – the only thing I did not anticipate or expect -happens so frigging commonly in intl. agencies.”

This next sentiment is critical as well, and points to the all-too-frequent “field promotion” phenomena.

“Mostly underqualified people given too much responsibility.”

This extended comment is from a (female) industry insider and affirms the point I make above about the “weakest link within any system/organization” problem.

“I often argue that Human Resources is one of the weakest departments in most aid organisations. Most, if not all, of my consultancy assignment came from personal relationships. I think I am fairly good at doing my job, but was I really the best candidate for those positions? There is no way to know. This is true for most – if not all – of my colleagues, and I am yet to meet anyone who got the job after applying to an open vacancy.

The problem is that it is not just excellent people who keep being offered dozens of assignments. Some of these people who are hired again and again are so blatantly incompetent, they should stop working in the aid sector, period. Others are just not the right person for the job. Posting people with limited English knowledge to English-speaking countries? Check. Asking an anger-prone, no-bullshit type of person to suddenly master the art of diplomacy? Check. These people might have been great in another context, but they are out of place now. Bear in mind I am talking mostly of people on short-term contracts: the issue is not really about firing them, but about not offering them new assignments after a dismal performance. And even in cases of staff on permanent contracts, it should not be too difficult to imagine a way to prevent them from being given roles for which they lack basic skills.

One of the problems, in my view, is that HR departments often deal only with the bureaucratic aspects of hiring staff. They send you the contract, they make sure you fill in and sign all the right forms and attach a recent medical certificate, and that’s about it. Hiring decisions are actually made by managers who do not necessarily have the skills, mindset and training to spot the best candidates. Another issue is why aren’t performance evaluations taken into consideration? I guess that either hiring managers don’t bother reading them, or supervisors fail to disclose their staff members’ failures.”

This male aid worker affirms the above and underlines some additional points related to staffing in a fluid and demanding sector.

“I’ve seen the reason for termination given as incompetence, but that was never the reason in reality. And incompetent people in all positions tend to get passed around unless they’re really bad (can only thing of one that eventually got permanently sideline, but it took lots and lots of drama creation from their side, so maybe it was more the interpersonal issues). The reality is, in most specific situations this industry needs warm bodies and a pulse is worth more than an appropriate technical background. Plus there are a lot of really, really maladjusted folks kicking around this industry. Normally shocking incompetence usual goes under the radar or can be excuse by ever-present extenuating circumstances. Sometimes doing a performance evaluation or reference check would just take too much time out people’s busy schedules. It’s very common for people to get no reference check at all, or a reference check is used as a reason to exclude someone. Considering the kind of environments people are expected to work together in, I’m surprised that even pure self-interest doesn’t lead to more due diligence.”

On another note, there are, at the end of the day, many reasons why an aid worker might engage in aberrant behavior that may or may not lead to being fired. That this line of work can be emotionally and physically brutal at times is a fact. As one aid worker pointed out,

“It [aid work] is a field where there is little work-life balance and the cumulative stress over the years leads to many of the things listed above. International aid folks are known to be pretty eccentric, traumatized, unbalanced, and needing for mental health support. All these things make it more likely that they will make bad choices which lead to being fired.”

Thoughts?

The data indicate that people do, rarely, get fired because of gross inappropriate behavior, to be sure, but it appears that personality clashes, especially with superiors, is a more common reason.

I was a bit surprised how strong the “incompetence does not get you fired” thread was throughout the 372 responses, but there you go. Having said that, as I look at other sectors both for-profit and not-for-profit one can find similar dynamics at play. Despite Donald Trump’s popularization of the phrase, “You’re fired!” in many sectors it is just not that common. In the US at least, people are forced out, leave as they see the writing on the wall, get transferred, downsized, “made redundant” in all manner of creative ways, etc. -all the reasons permutations mentioned above in our aid worker data- in lieu of getting the proverbial “pink slip.”

Is the aid sector really all that different? Certainly we do not have the data for any conclusion along that line but I offer the conjecture that any exceptionality is a matter of degree, not of kind.

Human Resource officers take note

Aid workers are frustrated by many aspects of their employment, especially when it comes to working with and dealing with the consequent actions of incompetent co-workers. This is certainly evidenced in the data from Q’s 48 and 49 and, of course, cannot come as a huge surprise to anyone in the sector. For me the take home from a HR perspective from the above includes at least considering these action points:

- Let proven competence relevant to positions drive hiring decisions.

- Have more extensive exit interviewing of all employees (make it a condition of final pay if necessary) and use those data effectively to make hiring and care-and-feeding policy decisions.

- Do not promote beyond credentialed expertise; sometimes nothing is better than an incompetent something.

- Consider more extensive psychological/personality testing of potential hires.

- Make more public and obvious rubrics/expectations for performance. There must be open and transparent terms of reference and standards of performance.

- Use every new hire, lateral move or promotion as an opportunity to move your organization in a positive direction, especially regarding weeding out the marginal and those who fail to grasp and hold true to the core missions of not just your organization but to those the aid sector in general.

- Network with your HR counterparts across the sector to work toward more standardization of hiring criteria.

- Make knowledge transfer a major priority by demanding overlapping deployments.

- Start in the interview process by messaging a more demonstrative “culture of firing” (as mentioned above) and reinforce this rhetoric with action.

And, finally, this last one from an industry insider who prefaced this suggestion with “…JD/TORs/SOWs are usually very badly written; HR risk-averse, cover-your-ass procedure makes it very difficult and process-intensive to outright fire someone.”

- Grow a pair: lose the hyper risk-aversion. If someone underperforms or is incompetent, document it, fire them, and move on.

A warning of a coming demographic change

The work force in the US and in much of the rest of the Western world is aging, and this demographic shift will have an impact on the aid sector in the not too distant future. This can be seen as good news. Organizational cultures with low staff turnover are slow to change, but those with rapid turnover can use this dynamic to bring about desired cultural change. Another post will have to be devoted to that topic, but, in short, this can be seen as a moment of crisis for the aid sector. We have all heard the trope that the Chinese character for crisis is the combination of danger and opportunity, and perhaps now is a time for the entire sector to devote some time looking into the future and planning for how to be more robust, effective and, at the very least, find a way to weed out the incompetent. There is too much at stake to do less.

This parting thought by one respondent sums up much of the above and offers a glimmer of hope for the future.

“There is no clear route into the sector to ensure the best of the best are employed and given opportunities. Its is essentially a cowboy industry where people are employed because of friends or for soft skills, or because of many years experience which does not necessarily equate to brilliance. As the sector slowly by slowly becomes more professional, incompetency is more noticeable and less tolerated.”

As always, please contact me with questions or comments.

Follow

Follow