Morality and Religion?

A moral life

Many is the time that I have read or heard it said by religious people that a belief in God is necessary to lead a moral life. If they are Christians, they may very well add that adherence to Christianity per se is necessary to be moral, or at least to enter heaven when the time comes. Without belief in God and religious rules as a guide, what would prevent a non-believer from giving in to every base and disgusting urge? Wouldn’t every atheist be a murderer and rapist? Without God, why not? Or so the thinking goes. Noted evangelist Benny Hinn said, “Do you know that every unbeliever is filled with a demon spirit?” Conservative Christian commentator and author Bill O’Reilly noted that when a society ceases living a religious life, “under God,” it will degenerate into anarchy and crime. Jewish author Dennis Prager has opined, “No God, no moral society.” Many other spokespeople for religion echo this view, as do a large percentage of Americans (according to a recent poll), with 53% agreeing with the notion that a person must believe in God to be moral.

Let’s turn to Seventh-day Adventism and the notion of end-times. One of this denomination’s foundational beliefs is the imminent Second Coming (advent) of Jesus Christ. William Miller, a lay Baptist preacher predicted in the 1830s and early 1840s that Jesus would return to Earth in 1844. The failure of that prediction caused much bewilderment and dismay among Miller’s followers, so much so that they referred to this (non)event as “The Great Disappointment.” Over the years several denominations arose from the Millerites, including Seventh-day Adventists.

One might well ask, “If a person believes that the world will end any day now, and the Final Judgment will be upon us, what is the point of attending to long-term worldly problems?” It takes a lot of planning to come up with solutions to endemic disease, poverty, environmental degradation, racial discrimination, crime, and so on. Is it worth spending time working on long-range solutions if we are living in the end-times?

And to circle back to the issue of morality, isn’t taking care of these problems—racial discrimination, poverty, crime, etc.—what being moral is all about? That, presumably, is at least partially what the Christian pundits listed above are thinking about when they consider a society lacking in morality. So, while those pundits are worried about wayward atheists, maybe Christians who concern themselves with the end-times being nigh are the ones neglecting their fellow humans, i.e., acting in an immoral manner.

Relevant survey results

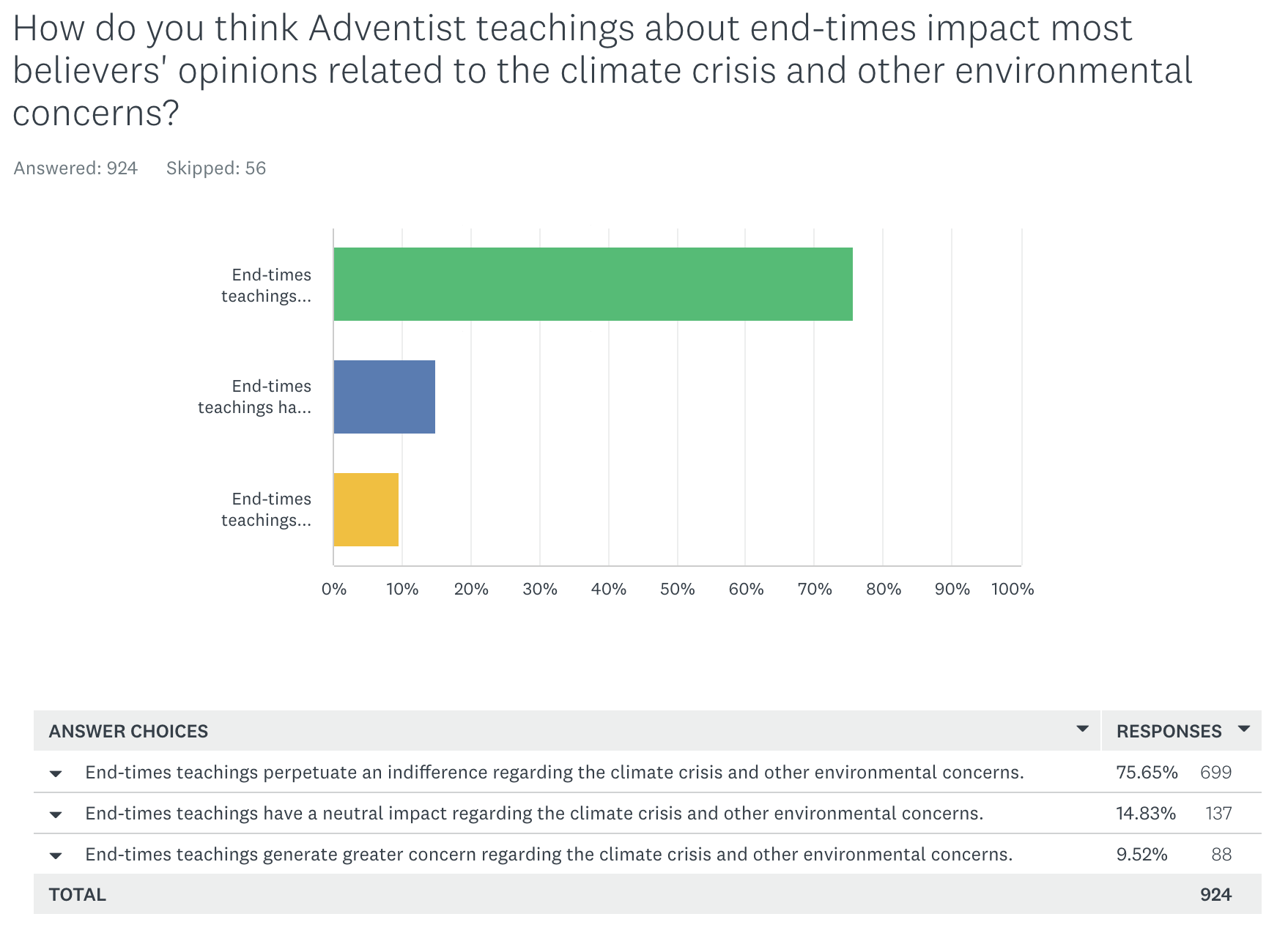

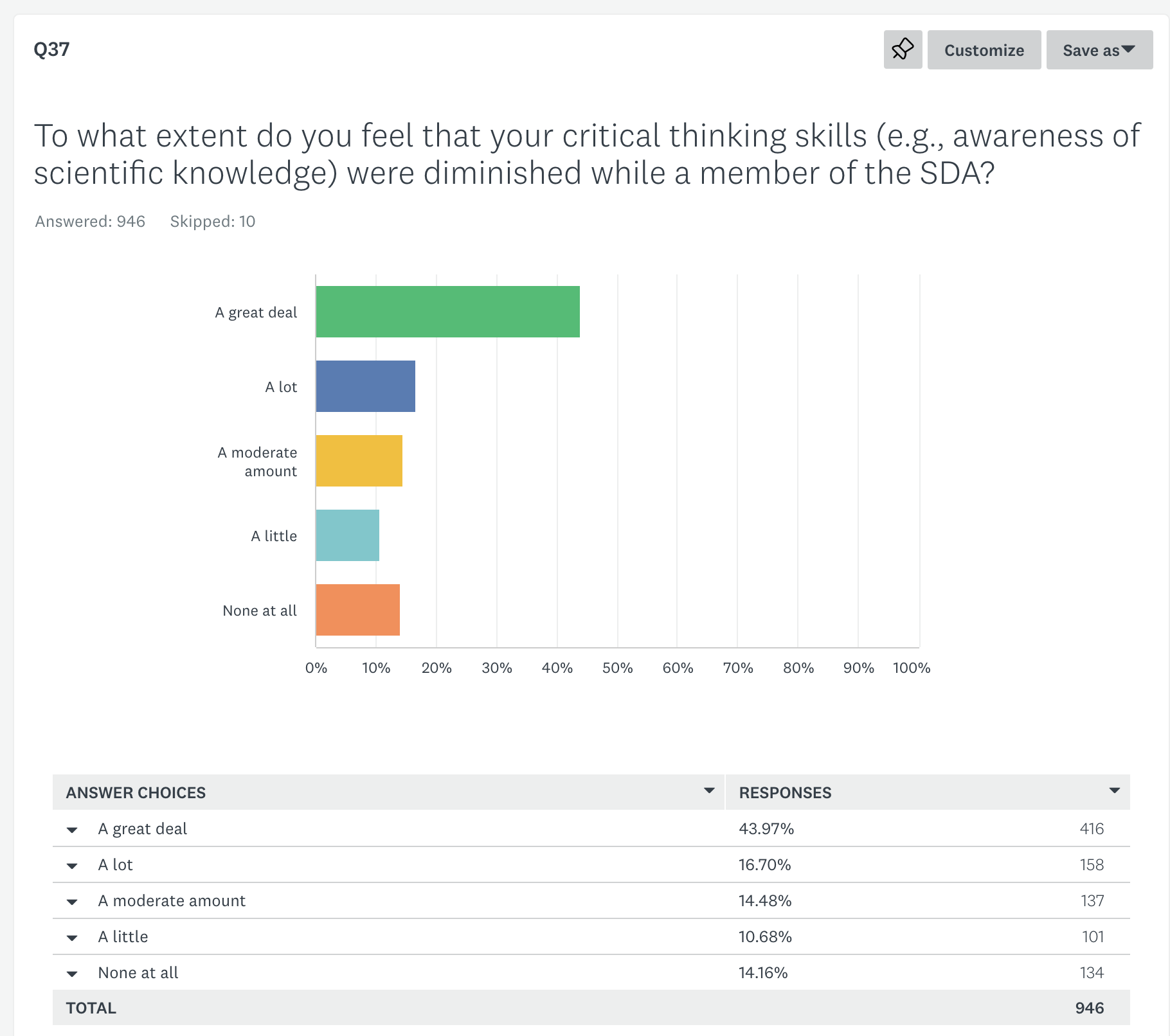

There are two questions on our Seventh-day Adventist survey that specifically address the issue of how the teachings of end-times affects members’ opinions of current worldly concerns.

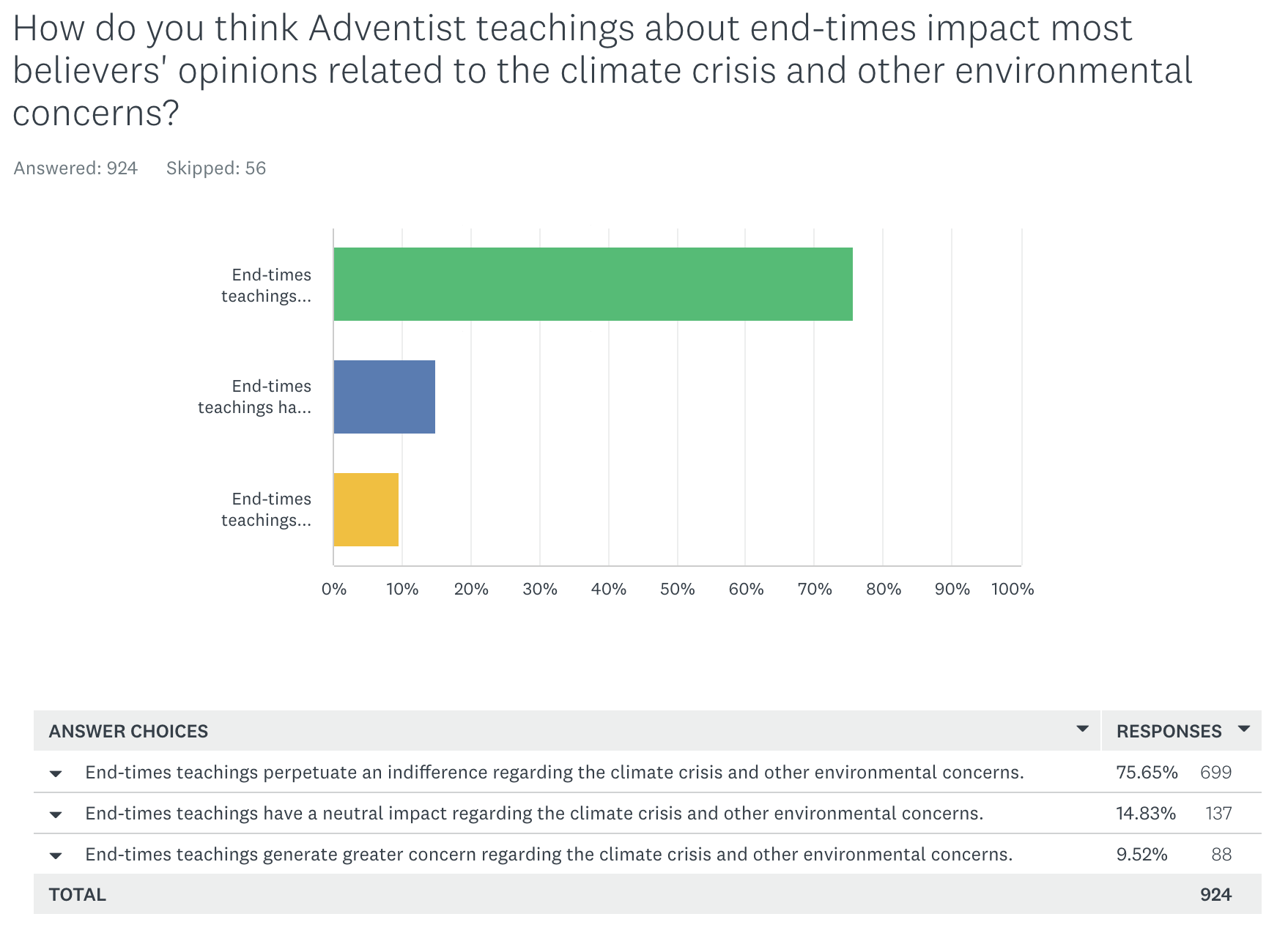

Question 35 poses, “How do you think Adventist teachings about end-times impact most believers’ opinions related to the climate crisis and other environmental concerns?”

Responses1 were:

End-times teachings perpetuate an indifference regarding the climate crisis and other environmental concerns. 77.5%

End-times teachings have a neutral impact regarding the climate crisis and other environmental concerns. 13.7%

End-times teachings generate greater concern regarding the climate crisis and other environmental concerns. 8.8%

Here are just a few comments offered by our respondents supporting these data:

“SDAs have always had the attitude that the Lord is coming soon so spend your time evangelizing rather than worrying about the climate or environment.”

“If you put all your belief eggs in the “Jesus coming soon” basket, you don’t think you’re going to be around to grapple with the effects of climate change. To believe otherwise would seem to be a denial of Adventism.”

“I have never in my life met an Adventist who believed climate change was real. They believe this is some government ploy to eventually enact the ‘Sunday law'”.

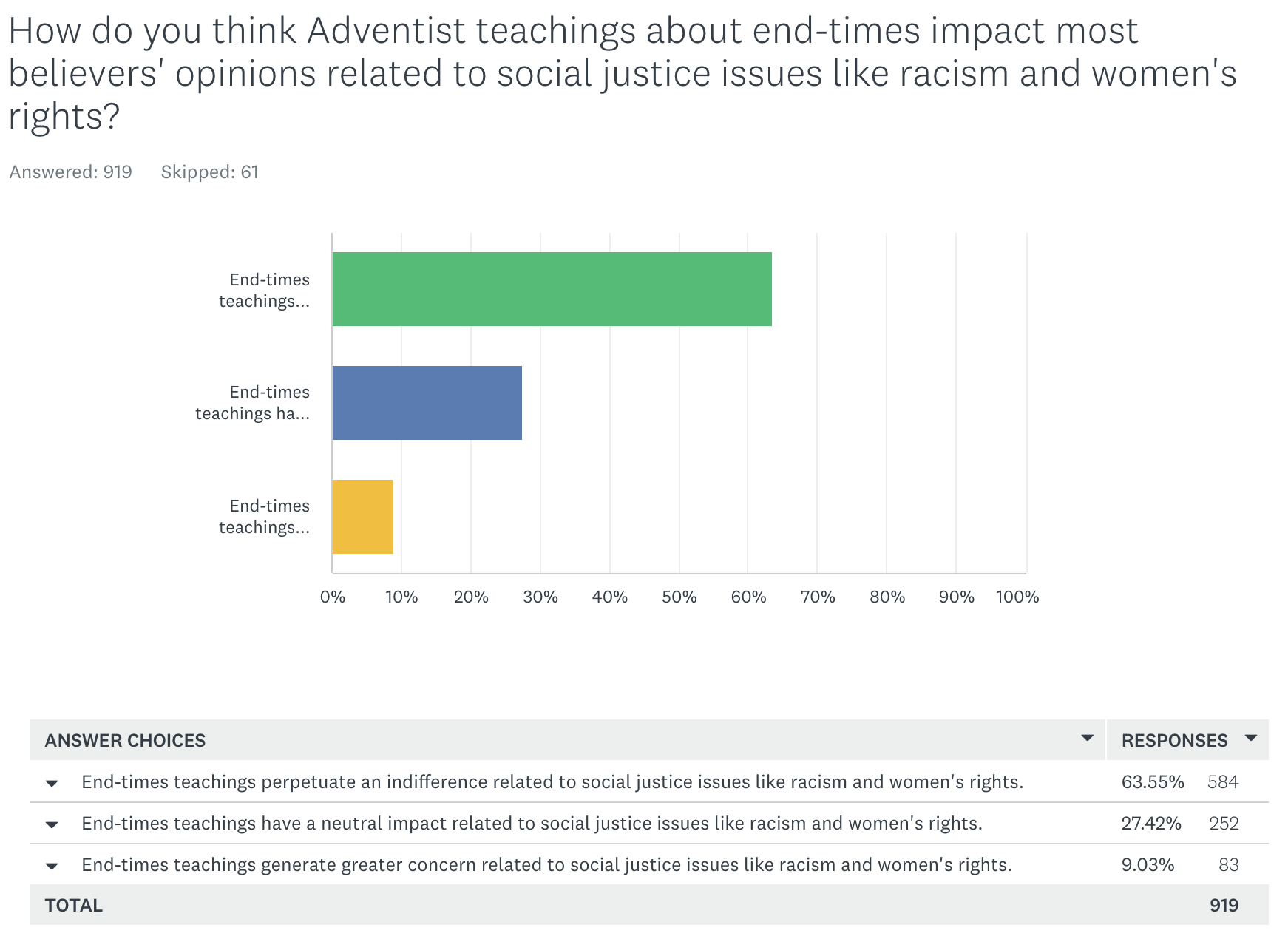

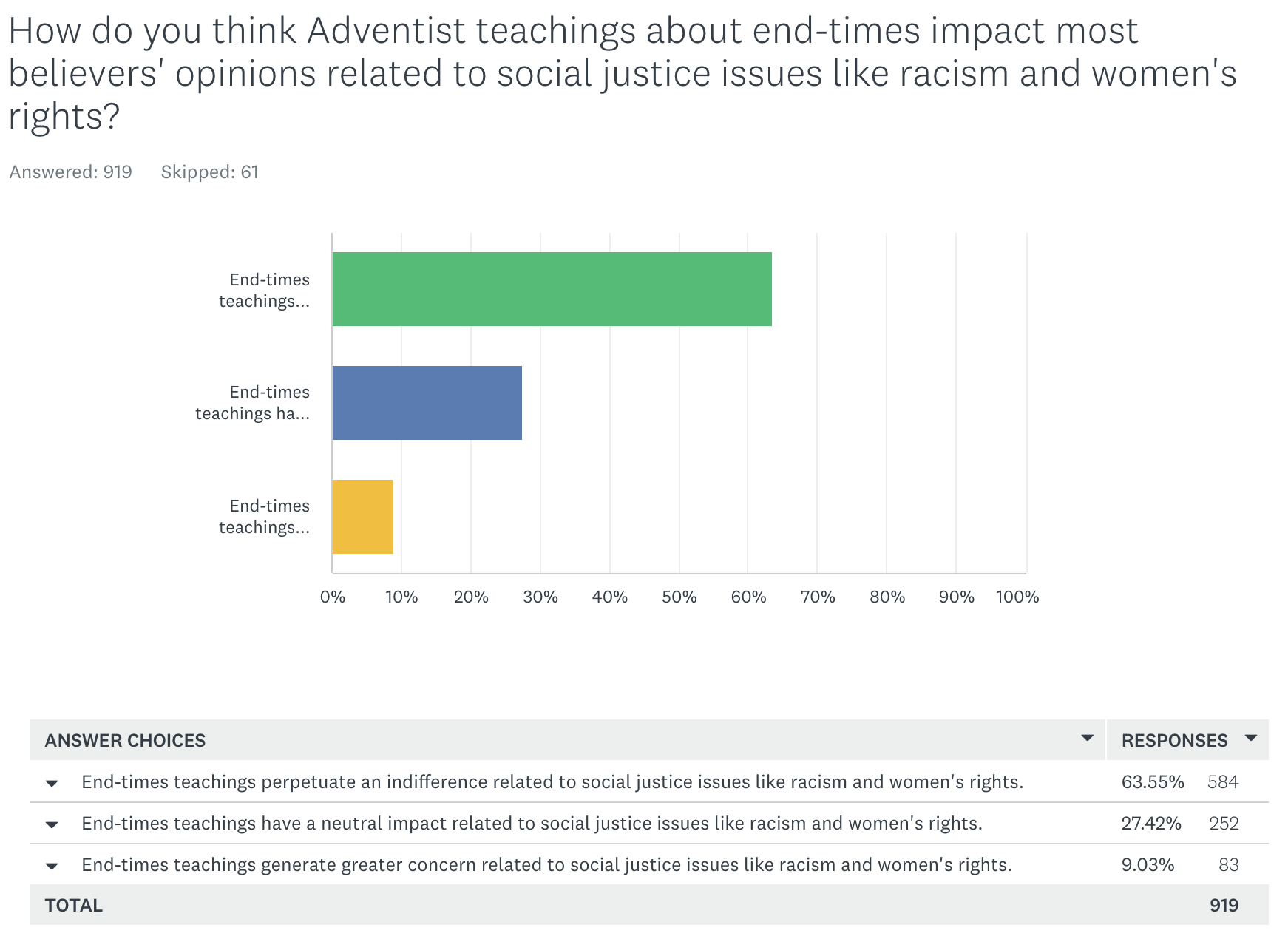

Question 36 asks, “How do you think Adventist teaching about end-times impact most believers’ opinions related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights?”

Responses were:

End-times teachings perpetuate an indifference related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 64.2%

End-times teachings perpetuate an indifference related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 64.2%

End-times teachings have a neutral impact related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 26.6%

End-times teachings generate greater concern related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 9.2%

Again, here are comments illustrating this perspective, the first one particularly passionate:

“‘This world is not my home, I’m just a passing through.’ Sentiments/lines like this perpetuate this indifference. Why would we take care of the planet, fight for rights- we are going to go live in heaven and the earth will be made new. ‘It’s supposed to ‘fall apart’ and ‘blow-up’ these are signs of the last days, this is good news that Jesus is coming again.’ Bullshit like this!”

“Most believers ignore issues and focus on “present truth” rather than social, political, and racial issues.”

“I disagree with the choice I chose. I do not thing end-times teachings perpetuate indifference toward racism and women’s rights. I think it UNDERGIRDS and FUELS abuse and mistreatment toward people in general, especially those who are culturally vulnerable such as POC claiming mistreatment, women — all women, and queer people — all queer people.”

This last statement is particularly damning and indicates immoral behavior is ‘fueled’ by the Adventist church. The majority of respondents indicate that Adventist teachings foster an indifference to environmental and social justice issues— current-day concerns requiring long-term solutions. If we look at caring about social injustice and environmental problems as issues of morality, which it is hard to imagine they are not, then these ex-SDA members are essentially saying (I my opinion) that their former church was encouraging them to take an immoral stance. They were being taught not to bother about these worldly matters.

The Second Coming

So, the Second Coming is imminent. But Christians have been saying it’s ‘imminent’ for 2,000 years. William Miller said it would occur in 1844. Jehovah’s Witnesses stated with certainty that it would occur in 1975. What’s to say that insofar as Jesus has put things off for so long already, he won’t wait another thousand years or more? (This is assuming that Christianity is true in the first place.) In the meantime, people are suffering, the planet is degrading. And we should do nothing because Jesus will return any day now, like religious leaders promise he is going to do for the last many hundred years? How can this be moral?

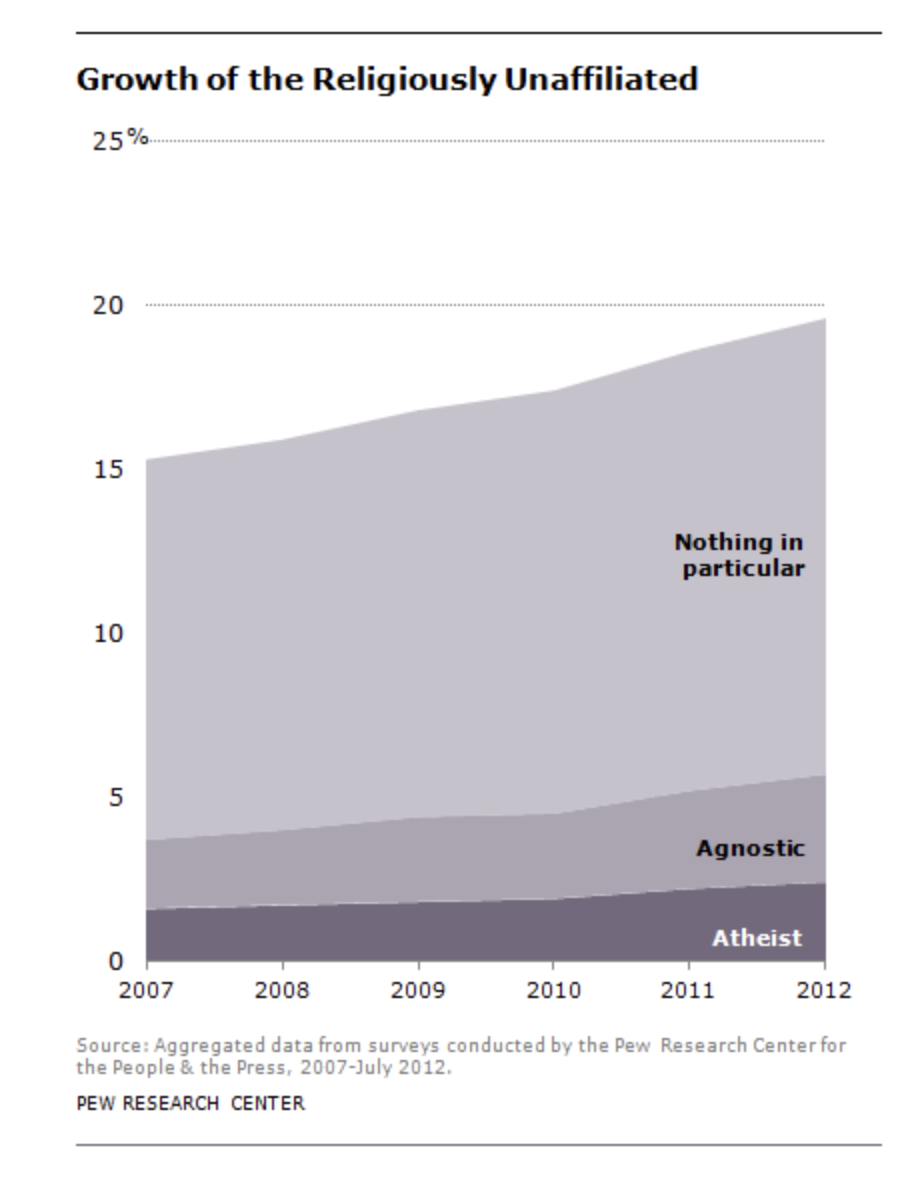

As I have noted in an earlier post, more and more Americans over the past decades have been turning away from religion or not being raised in religion to begin with. The category called “nones,” which includes those who are unaffiliated with any particular religion (yet who may still be religious or spiritual in some way), as well as agnostics and atheists, has been rising dramatically in numbers in recent decades. The percentage of such Americans was trivial until the early 1990s. Then, about 1992, things really started to change. A combination of data from the General Social Survey and the Pew Research Center for the next many years (until the present, essentially), shows a huge uptick in those turning away from the dominant religion of the USA, i.e., Christianity. And they were not turning to other religions, the data shows.

Do the data bear out the ‘you must have religion to be moral’ argument?

If all the doom-and-gloom prognosticators behind the pulpits were correct about the consequences of turning away from God (generally) or Christianity (specifically)—the murder, rape, and general running amok– then surely we would expect the decline in adherence to Christianity in this country to be reflected in rising crime numbers. That is, the much ballyhooed relationship between atheism and crime should be clearly visible in statistics on crime.

So let’s take a look. In 1991, the murder rate per 100,000 people in the USA was 9.8. That is, 9.8, or almost 10 of every 100,000 Americans, were murdered. Or, if you prefer to think on the millions level, that’s about 100 per million. In absolute numbers, it was about 25,000 Americans.

The following year, 1992, was the start of something big that nobody predicted. The murder rate decreased to 9.3 per 100,000. The decreases continued year by year (with one exception) throughout the 1990s, so that by the year 2000, the murder rate in the USA stood at 5.5 per 100,000. This represented 16,000 Americans. Thus, throughout the 1990s the murder rate in this country was cut almost in half. This was indeed a spectacularly positive turn of events.

And it wasn’t just the crime of murder. The same pattern held true for attempted murder, aggravated assault, rape, and other violent crimes. Incidentally, the numbers for these trends all come from the Uniform Crime Report produced annually by the FBI. Another source, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), has generated its own annual reports, which concur with the FBI results, with the exception that the NCVS doesn’t collect information about murder. This huge decrease in the rate of crime during the 1990s in America is referred to by criminologists and others who study crime patterns as the Great American Crime Decline. Its causes are debated, but the fact that it occurred is agreed upon.

own annual reports, which concur with the FBI results, with the exception that the NCVS doesn’t collect information about murder. This huge decrease in the rate of crime during the 1990s in America is referred to by criminologists and others who study crime patterns as the Great American Crime Decline. Its causes are debated, but the fact that it occurred is agreed upon.

Beyond 2000, murder and other crime rates fluctuated somewhat, but by 2014 the murder rate stood at 4.5 per 100,000. This was a 51-year low, not seen since the 1963 rate of 4.6 per 100,000.

So what can we say about religiosity, in particular adherence to Christianity, and crime, especially in this country? Well, it would seem very difficult to argue that religiosity is a necessary bulwark against murder, rape, and the like. Just as Americans began to turn away from religion in large numbers (starting about 1992), serious crime started taking a big plunge. If anything, what the religious leaders spoke about the consequences of turning away from Christianity have been the exact opposite of what they were predicting.

Incidentally, the Great American Crime Decline coincided with the presidency of Bill Clinton, whom Christian conservatives derided as soft on crime and weak on Christian morals. The year 2014, the 51-year low in the murder rate, was during the administration of Barack Obama, whom Christian conservatives castigated for being morally weak, non-Christian, Muslim, and so on.

More on crime and religion

A quick look at the religiosity of states is also instructive. The Bible Belt is rightfully known for its high percentage of citizens who worship God, attend church, and manifest other signs of religiosity. The states that are considered to be within the Bible Belt may be disputed, but I provide here a list that almost everyone would agree on, along with homicide rates for the year 2021 (according to the Centers for Disease Control).

Homicide Rate

Alabama 15.9

Arkansas 11.7

Georgia 11.4

Kentucky 9.6

Louisiana 21.3

Mississippi 23.7

Missouri 12.4

North Carolina 9.7

Oklahoma 8.9

South Carolina 13.4

Tennessee 12.2

By comparison, let’s take a look at the states that scored the highest in irreligiosity (being defined much as nones described above), according to a Pew Research poll, along with their homicide rates.

Homicide Rate

Massachusetts 2.3

New Hampshire 0

Vermont 0

Washington 4.5

Perhaps you have noticed something remarkable. Every state in the Bible Belt has a homicide rate that is higher (often much higher) than that of every one of the most irreligious states. The Bible Belt states tend, in fact, to have the highest murder rates in the US. Of course, there is much that goes into the reasons for a state’s murder rate, but it nonetheless should give a thinking Christian pause that Bible Belt states are so flush with murder compared to irreligious states.

What is to be said of all this? I think a point could be made that the Christian pundits and preachers are ignorant of the facts—that non-religious people actually are not, on average, committing crimes at high levels, that being steeped in Christian doctrine doesn’t preclude people from committing felonies. According to the Christian religionists, the results should be strikingly obvious: the non-believers should be committing crimes in a grossly disproportionate manner compared to the religious, and as the nation becomes more secular, it should be having hugely more amounts of crime. But, actually, the opposite is true. It would seem that atheists are not running wild in the streets as pessimistic preachers would have us believe. And in some cases, such as the teaching of end-times, religion may lead to immoral behavior.

1These are the responses from the English version of the survey only. Our final report will aggregate the data from all versions.

Follow

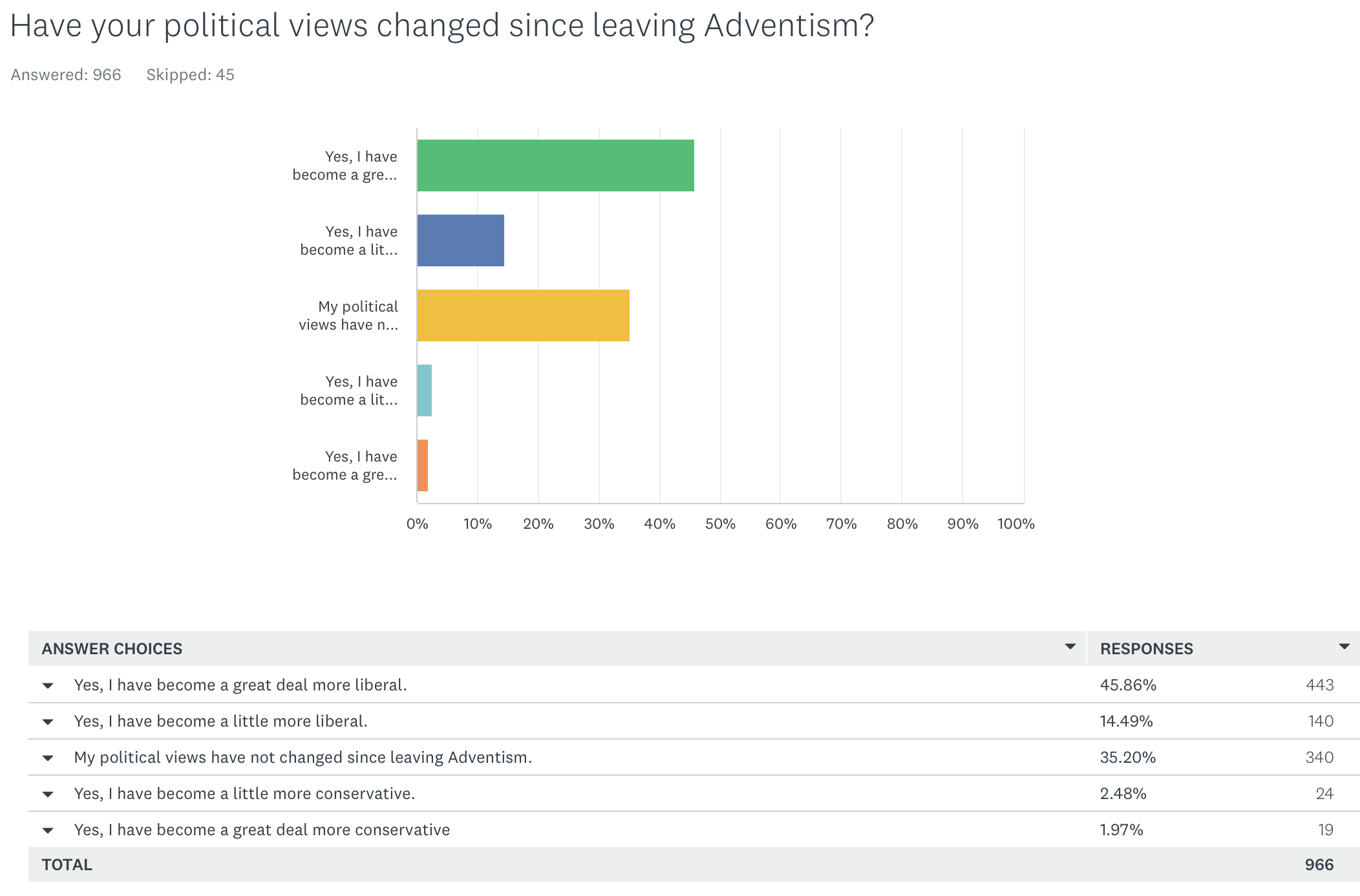

Follow Those subscribing to Christianity are falling as a percentage of Americans. To the extent that the former Adventists of our survey represent this secularizing trend, then we might predict a more politically liberal electorate as time goes on. This, of course, could have major ramifications in elections.

Those subscribing to Christianity are falling as a percentage of Americans. To the extent that the former Adventists of our survey represent this secularizing trend, then we might predict a more politically liberal electorate as time goes on. This, of course, could have major ramifications in elections.

End-times teachings perpetuate an indifference related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 64.2%

End-times teachings perpetuate an indifference related to social justice issues like racism and women’s rights. 64.2% own annual reports, which concur with the FBI results, with the exception that the NCVS doesn’t collect information about murder. This huge decrease in the rate of crime during the 1990s in America is referred to by criminologists and others who study crime patterns as the Great American Crime Decline. Its causes are debated, but the fact that it occurred is agreed upon.

own annual reports, which concur with the FBI results, with the exception that the NCVS doesn’t collect information about murder. This huge decrease in the rate of crime during the 1990s in America is referred to by criminologists and others who study crime patterns as the Great American Crime Decline. Its causes are debated, but the fact that it occurred is agreed upon. said, “None.”

said, “None.” atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular.” From 2007 to 2021 the “nones” category steadily increased from 16% to 29% of the adult population of the US. This is a 13-percentage point increase, which is almost identical to the 15 percentage point decrease incurred by Christians. It would certainly appear that the Christians’ loss is the nones’ gain. Bear in mind, as well, that the 16% to 29% increase in nones represents a near-doubling of their numbers over this relatively short time span.

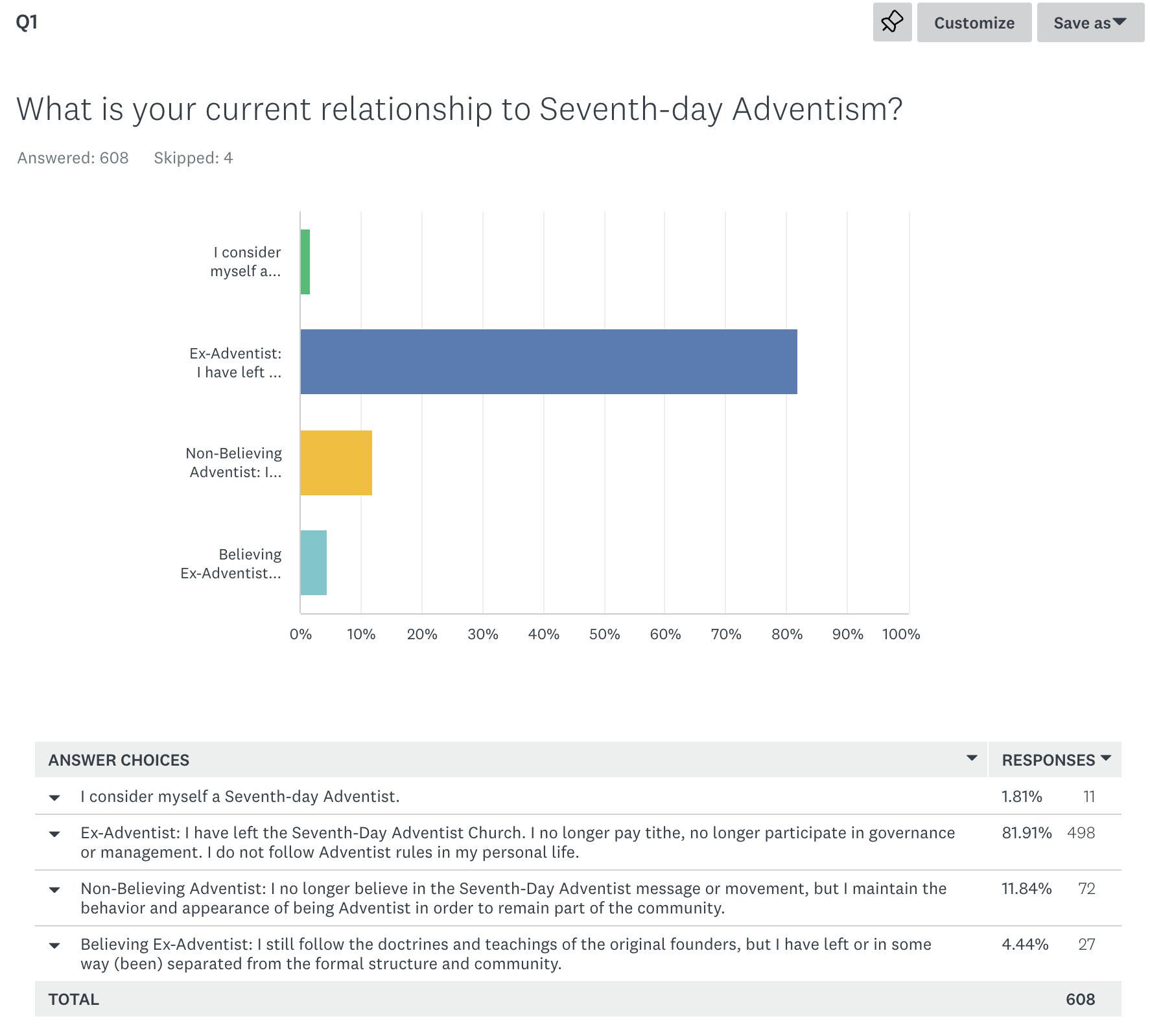

atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular.” From 2007 to 2021 the “nones” category steadily increased from 16% to 29% of the adult population of the US. This is a 13-percentage point increase, which is almost identical to the 15 percentage point decrease incurred by Christians. It would certainly appear that the Christians’ loss is the nones’ gain. Bear in mind, as well, that the 16% to 29% increase in nones represents a near-doubling of their numbers over this relatively short time span. respondents indicated they were “Non-Believing Adventist: I no longer believe in the Seventh-Day Adventist message or movement, but I maintain the behavior and appearance of being Adventist in order to remain part of the community.”

respondents indicated they were “Non-Believing Adventist: I no longer believe in the Seventh-Day Adventist message or movement, but I maintain the behavior and appearance of being Adventist in order to remain part of the community.”  God may not be dead, but she is losing popularity

God may not be dead, but she is losing popularity America’s failure. If secular, democratic, diverse, and pluralistic America survived, then wouldn’t that prove that we evangelicals were wrong about God only wanting to bless a “Christian America”? [p. 298-299]”

America’s failure. If secular, democratic, diverse, and pluralistic America survived, then wouldn’t that prove that we evangelicals were wrong about God only wanting to bless a “Christian America”? [p. 298-299]”