“The first thing a refugee asks for upon arrival at a camp is not water or food, but the Wi-Fi password. A smartphone has become a basic humanitarian need because it allows displaced people to connect with loved ones they’ve been separated from.”

-Turkish telecom CEO Kaan Terzioglu at DAVOS, 2018

Mobile and wifi access a basic human right?

Just now I am writing in a local coffee shop, surrounded by colleagues, students, and staff at my university, literally 100% of whom are connected via cell and/or wifi. In the global north where I live connectivity is essential, even vital, for day to day life.

Is the same true for the rest of the world, especially those who are now refugees? More specifically, in our globalized world, is cell and wifi access essential and therefore a basic human right?

22 February 2020

I’ll argue absolutely yes.

Rohingya denied

Over two months have passed since the government of Bangladesh directed the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) to order telecom companies to stop selling SIM cards and shut down mobile phone services to almost one million Rohingya refugees living in refugee camps.

Within days of this action Human Rights Watch took the position that this action is bound to have negative impacts, stating,

“Bangladesh authorities have a major challenge in dealing with such a large number of refugees, but they have made matters worse by imposing restrictions on refugee communications and freedom of movement.”

I posed this statement to a Rohingya contact in the refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar,

“The issue as I understand it is that the Bangladeshi government wants to cut down on activism in the camps and it is heavily restricting cell phone usage and WiFi access. This is cutting down on communication both within the camp and from the camp to the outside world including friends and relatives, but also people who are interested in understanding and helping the Rohingya.”

He responded ‘Correct.’ All of the Rohingya refugees I have talked with disagree with the new restrictions, and now, more than two months later, their frustrations are rising. They are being denied the right of connectivity and freedom of communication, and this is an additional source of strain in their lives.

One Rohingya refugee describes the situation,

“We don’t have internet access. Authorities and even Bangladeshi public seize phones of Rohingya if they find.”

Another added,

“A few days ago I was arrested by police for using a cell phone while I was working in the office. I need cell phone in office time to send reports, details and data, use Whatsapp and gmail. But they didn’t have a look while I was encircled by police. That’s our life in camp. Then I was given a fine.”

He went on to say,

“About WiFi, a refugee isn’t allowed to use it. But some Bangladeshis around camp buys WiFi then sells the password to the refugee for the profit.”

Happening now in Myanmar

On February 3 the Ministry of Transport and Communications in Myanmar issued a directive to internet and telecommunications providers to cease mobile and wifi access in five townships. The MToC cited security requirements and public interest as the justification for this action. In a joint statement dated 13 February, 28 organizations joined Human Rights Watch in calling on the government of Myanmar to immediately lift restrictions on cellular and wifi access. Similar actions have been taken by the government of India in Jammu and Kashmir, with this region now without access for over 200 days.

In Myanmar there were protests against this stoppage of mobile and wifi access. Various groups, mostly university students, held protest marches in Sittwe and Yangon.

22 February 2020.

How important is connectivity?

Control over mobile and wifi access is “an increasingly popular authoritarian tool” and this trend runs counter to basic human rights.

In 2016 the UNHCR published Connecting Refugees: How Internet and Mobile Connectivity can Improve Refugee Well-Being and Transform Humanitarian Action where they took a strong position, stating in their “Vision of Connectivity for Refugees”,

“UNHCR aims, through creative partnerships and smart investments, to ensure that all refugees, and the communities that host them, have access to available, affordable and usable mobile and internet connectivity in order to leverage these technologies for protection, communications, education, health, self-reliance, community empowerment, and durable solutions.”

“Refugees deem connectivity to be a critical survival tool in their daily lives and are willing to make large sacrifices to get and stay connected.”

In the concluding section to this document they state,

“If and when refugees are reliably connected to the internet and are able to purchase mobile connectivity, not only will they be better equipped to support themselves and their communities, but also they will find every area of humanitarian support boosted by the increased sharing of information and better communication.”

These examples of how connectivity is important are listed (p.31):

- Protection (e.g., asylum process, hotlines and incident reporting, etc)

- Community based protect (e.g., “Have greater access to information and be in a better position to identify its needs and lobby effectively for help and support.”

- Education (e.g., being able to access educational resources)

- Health (e.g., monitoring and reporting health needs)

- Livelihoods and self reliance (e.g., allowing for online businesses and remote work)

To this list I’ll add that access to cell and wifi is essential all over world, and especially in the ‘global South’ (the majority world) regarding the transmission of remittances. According to the World Bank, in 2018 $529 billion was sent to low and middle income nations around the globe, significantly dwarfing the $27.3 billion in humanitarian assistance that same year. Slowing, or worse yet, cutting, the flow of remittances by limiting wifi and cell connectivity will have a major -and in some cases life and death -impact.

Finally,

“Indeed, all areas of humanitarian response – from food and nutrition to water, sanitation and hygiene, to camp management and coordination – will benefit from a connected refugee population as services and communication with populations of concern will be easier and more reliable. Large- scale innovation in service delivery will become possible. The challenge and opportunity is to get refugees connected so that this transformation can begin.”

In 2017, this from OCHA,

“This year, a record-breaking 65 million people are on the run, having been displaced by conflict and violence. If averages prove true, most of these people will remain displaced for 19 years or more.

Whether a displaced person lives in a camp or a host community, their connectivity to mobile services and the Internet is not only a lifeline but also a key to success.”

Renew discussion with Bangladeshi government?

Should the retractions on cell and wifi access in the Rohingya refugee camps be lifted? If you ask the Rohingya they will certainly say yes. Given the position strongly in favor of connectivity by the UNHCR outlined above, humanitarian work, I am forced to assume, is hindered on many fronts. The efforts of humanitarian workers are handicapped both by having weaker cell and wifi access in the camps and by dealing with an affected community now increasingly stressed.

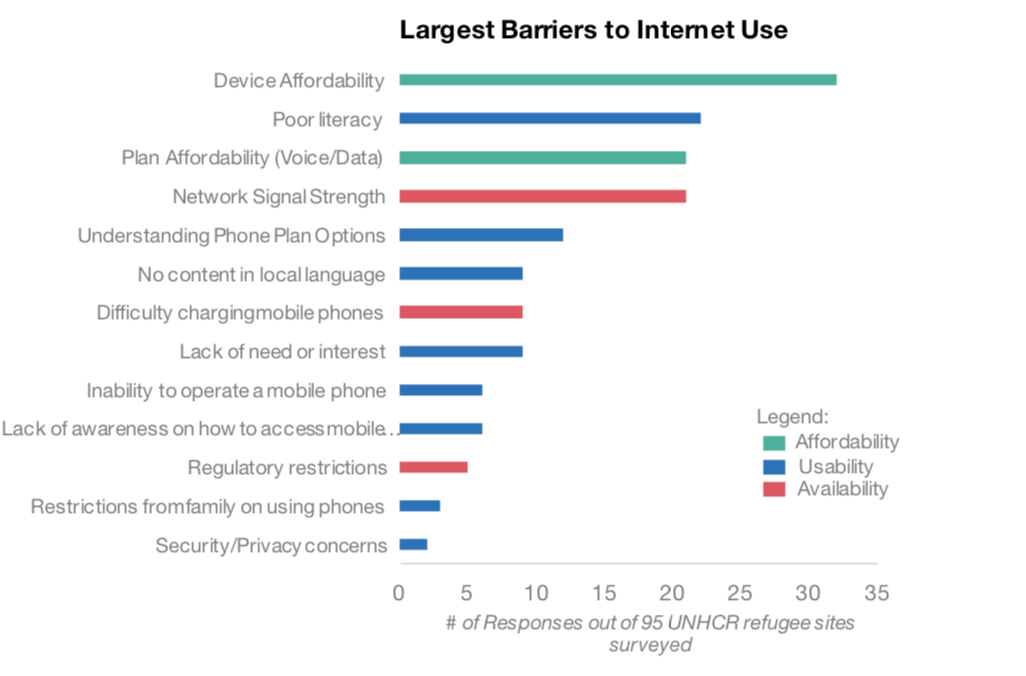

Though ‘regulatory restrictions’ does appear on the UNHCR list of “Largest Barriers to Internet Use”, perhaps in the case of the Rohingya since September, this barrier should be listed as number one.

What are the responsibilities of the host nation?

For many decades now Bangladesh has been doing an enormous job hosting refugees from Burma, and it is certainly their right to control what goes on within their borders. But should limits to their power be considered when the exercising of these powers deny basic rights to Rohingya refugees, and if so, what body has the right to interfere? No small questions, these.

The statement that connectivity is a basic human right is surely open to question. And it certainly raises the larger question of what entities can and should use their power to control such access. In a humanitarian response we must ask ‘who controls the lives of refugees, housed in large camps, with restricted mobility and no way of knowing how long they might be forced to stay in these conditions?’

Let me know your comments and feedback. Contact me at arcaro@elon.edu.

Follow

Follow