Warning: This is a long read at 3900 words and with numerous hyperlinks.

“It seems obvious that relevance should be a basic test of humanitarian assistance. If people don’t receive what they really need in a crisis, something is going wrong.”

—Sophia Swithern, Background paper for #alnap32

The relevance question

Thoughts on being a more ‘relevant’ as a humanitarian worker

Being a humanitarian worker frequently involves navigating between many cultures all while responding to the needs of people experiencing some form of extreme crisis. It is tough work, in part because dealing with ‘other’ people demands intellectual and emotional effort focused on the critical goal of maintaining relevance. Critical questions related to relevance include:

- Are my actions appropriate, ethical, and addressing the real needs of the affected communities?

- Are the actions of my organization appropriate, ethical, and addressing the real needs of the affected communities?

- Are the actions of the humanitarian sector as a whole appropriate, ethical, and addressing the real needs of the affected communities?

Addressing these questions is not a quick, easy, or a “one and done’ process. Mindful reflection on relevance must take into consideration a myriad of factors. Most effectively done, at least some of this this reflection should take place in diverse settings where the conversation can include a full range of perspectives, generating new insight on old questions and generating new ones for exploration. One important consideration is how the question of relevance is framed.

Not a monolith

Before we proceed further, some simple truths: Despite the appearance from 35,000 feet, the humanitarian sector is not a monolithic whole. Humanitarians are not a monolithic whole. Parts of the globe, nor the peoples who populate them, are not monolithic wholes. Affected communities are demonstratively not monolithic wholes. Donor entities are not a monolithic whole. Nor are any of the above static entities, unchanging and unconnected to the others. The crises to which humanitarians respond are not monolithic, some are ‘natural’ disasters, others human conflict; each is very different, and each moves along the response, recovery, development continuum at its own pace (or not at all).

Hence, though it is obvious to say, none of the above should be treated, either analytically or in practice as if they were static, isolated, or monolithic wholes.

The same can be said of each of us. We are all much more than just our title or the one role we are playing this moment. We are not static, isolated, or flat, unidimensional beings. By better understanding the complexity in our lives and minds we are better equipped to see complexity in our professional lives as humanitarians. Acting relevant demands nuanced awareness of ourselves and the world in which we live and act.

Must read for all humanitarians

In her background paper for this years ALNAP meeting in Berlin entitled “More Relevant? 10 ways to approach what people really need“, Sophia Swithern offers deep insights into what she calls the ‘relevance question’ and provides detailed and insightful analysis on how the question must be framed. Her introduction begins with a clear statement of problem, and then proceeds to raise some very robust observations and questions:

“It seems obvious that relevance should be a basic test of humanitarian assistance. If people don’t receive what they really need in a crisis, something is going wrong.” (page 1)

“The relevance test raises fundamental questions of knowledge, power and culture. How best to understand what’s most relevant when people’s needs are diverse, dynamic and sometimes at odds with expert views? Who gets the power to decide what’s relevant and how? To what extent can humanitarian aid be culturally and contextually relevant, while upholding principles and delivering on time and at scale? Indeed, is it possible for the western- bred humanitarian system to transcend its origins in order to do so? The relevance test also raises inevitable questions about humanitarian politics, structures and the resources of the response. Are current systems getting in the way? What kinds of collaboration are possible? And what kind of funding, staffing and expertise would it take to do things better?” (page 4)

On page 7 she gives us her working definition for relevance, to wit, “…relevance is being in line with the priority needs of affected people.”

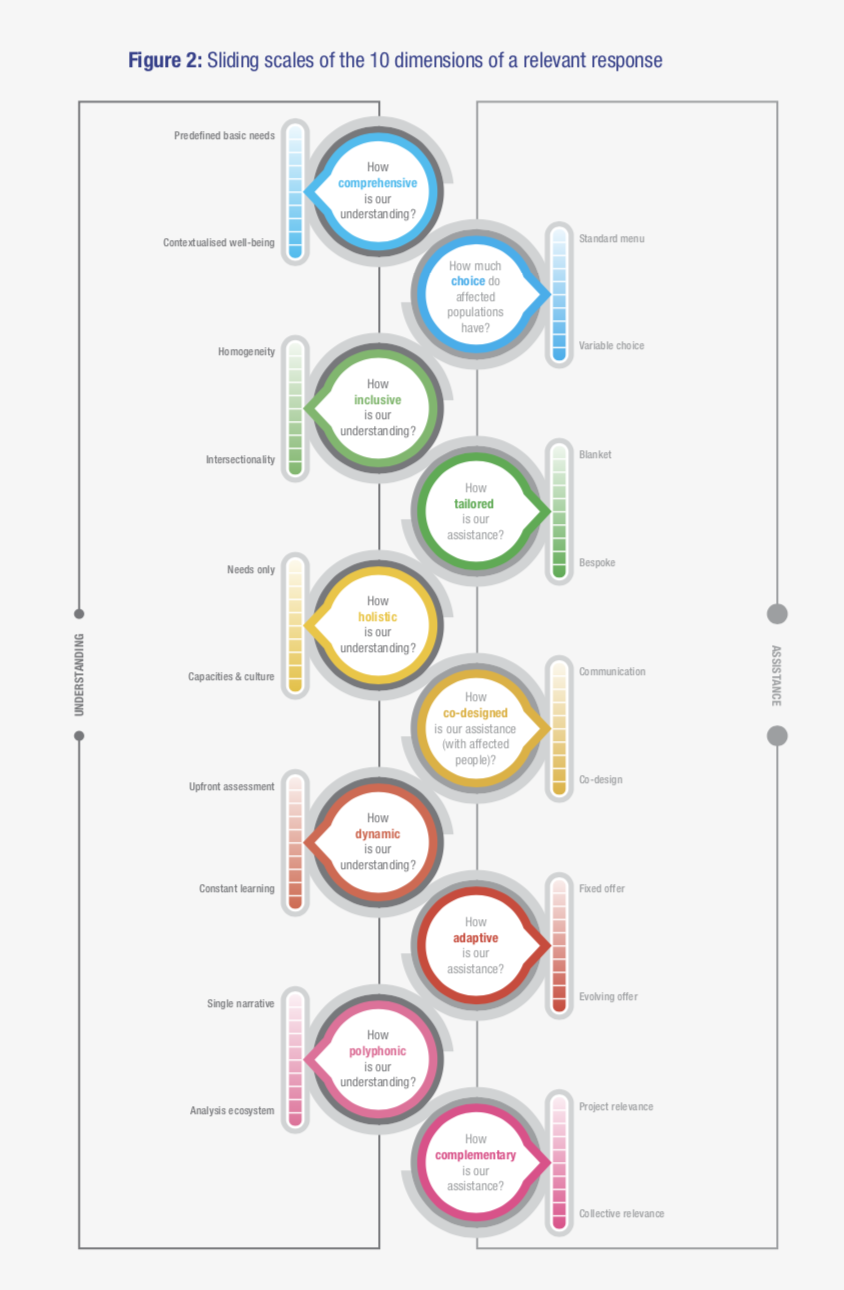

Swithern’s framing of the question provides tools with which we are able to generate useful, response specific questions and possible solutions. The backbone of her framework is the 10 dimensions of a relevant response seen here (click on image to enlarge). She breaks these dimensions down into two categories, understanding and assistance. Each question in turn is refined with a scale depicting the range of possible answers, with one end of the range representing (in most cases) the desired type of answer.

Understanding includes the questions

- How comprehensive is our understanding?

- How inclusive is our understanding?

- How holistic is our understanding?

- How dynamic is out understanding?

- How polymorphic is our understanding?

Assistance includes these questions

- How much choice do affected populations have?

- How tailored is our assistance?

- How co-designed is our assistance (with affected people?

- How adaptive is our assistance?

- How complementary is our assistance?

In her concluding remarks Swithern suggests,

“If relevance means a close match between response and what people most need, then as we’ve seen, this forces us to think hard about most aspects of humanitarian action. The relevance test reaches wide and deep.

We have seen how relevance and appropriateness are inextricable: the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of humanitarian action are both important if people are to have their needs met – for their tangible priorities such as food, as well as their intangible priorities such as dignity. This takes us beyond simplistic ideas of supply and demand and encourages us to think about humanitarian assistance as much relational as transactional.

We have also seen the blurred line between understanding what’s relevant and responding to it, that these are iterative rather than discrete processes. And while there is much room for improvement in understanding needs, there is not a simple equation to be drawn between more information ‘in’ and more relevant response ‘out’. This is not only because of limitations in decision-making and prioritisation, but also because subjectivity and complexity pose limits to how much we can know and provide what’s most relevant.” (emphasis added)

Perhaps the most important point she makes here is that understanding and responding to questions of relevance is an iterative process. This means that answering the relevance question, done well, means ongoing efforts by those who are in a position to guide a humanitarian response. That raises the very important question of power. Who within the humanitarian ecosystem has the position and privilege to ask these questions about relevance in the appropriate contexts and in a timely fashion? One answer to that question is, well, everyone, including donor entities, humanitarians, and the affected community.

Let us turn now to the questions of position, power, and privilege.

Maximizing relevance

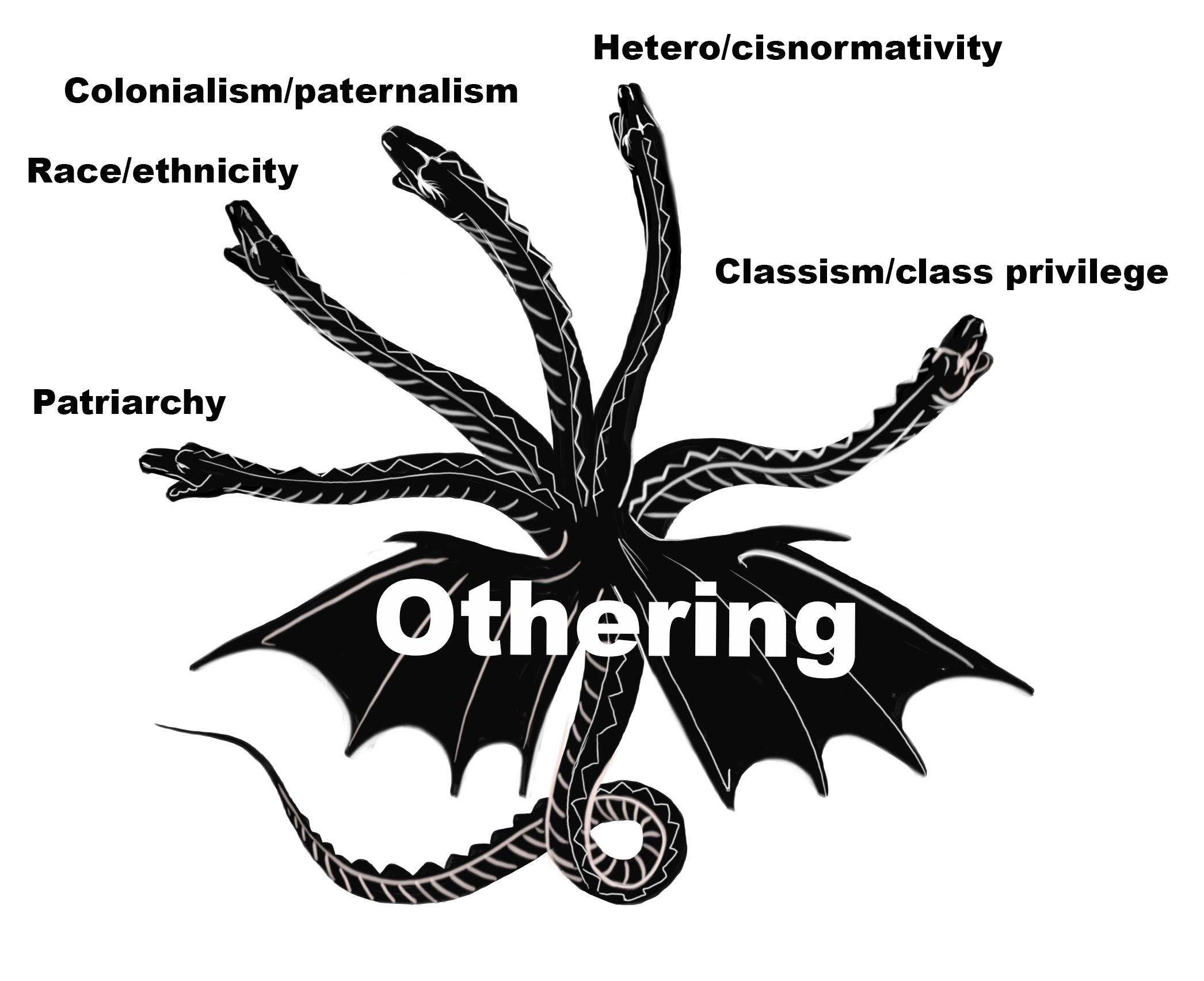

Below I addresses a pervasive issue in the humanitarian sector, namely ‘othering.’ Understanding at a deeper level the process of ‘othering’ better can make for more relevant actions, at least that is my hope as I invite you to read the remainder of this post.

Lessons from the Nataruk massacre

There is evidence of violence between groups of hunting and gathering bands 10,000 years ago in Kenya that appear to have included “‘extreme blunt-force trauma to crania and cheekbones, broken hands, knees and ribs, arrow lesions to the neck, and stone projectile tips lodged in the skull and thorax of two men.’ Four of them, including a late-term pregnant woman, appear to have had their hands bound.”‘

Ethological evidence indicates that our closest relative, chimpanzees, are quite capable of attacking and killing rivals, providing support for the premise that inter-group enmity is woven into our basic nature. Our tendency to other is evidenced in every corner of the world all through human history.

‘Othering’ is basic to our species; there has always been an ‘us’ and ‘them’. Perhaps it is best explained as an evolved mechanism functioning to maximize both individual and group fitness, it is an adaptive mechanism. Othering is part of our genetic motherboard.

Othering explained

Though the exact origin, at least for some, is unclear, many scholars agree one of the earliest uses of the term ‘othering’ comes from sociologist Edward Said’s classic 1978 book Orientalism. This term is inclusive of the entire range of marginalizing ‘isms’ and phobias including (but not limited to) ethnocentrism, racism, fascism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, and so on.

The semantic tool here is that Said has turned a noun into a verb, as in ‘to other’ some one or some group, to separate them from us.

Perfectly on point, John A. Powell and Stephen Menendian offer a detailed, timely, and very informative article entitled “The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging” which begins with this broad, but I think accurate, statement:

“The problem of the twenty-first century is the problem of ‘othering.’ In a world beset by seemingly intractable and overwhelming challenges, virtually every global, national, and regional conflict is wrapped within or organized around one or more dimension of group-based difference. Othering undergirds territorial disputes, sectarian violence, military conflict, the spread of disease, hunger and food insecurity, and even climate change.”

The quotation below from another article by S. R. Moosavinia, N. Niazi, and Ahmad Ghaforian comparing Orientalism to George Orwells Burmese Days presents the concept and also anticipates some points I’ll cover below.

“Orientalism is closely related to the concept of the Self and the Other because as Said points out in his second definition of Orientalism, it makes a distinction between the Occident, i.e. self and the Orient, i.e. the Other, since the analysis of the relationship of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’ is at the heart of Postcolonialism and many define Postcolonialism in terms of the relationship of the self and the Other. For instance, Boehmer emphasizes that ‘Postcolonial theories swivel the conventional axis of interaction between the colonizer and colonized or the self and the Other’.”

As an aside, I recognize the irony that Orwell’s book discusses the origins of one of the most tragic cases of ‘othering’ burning today in Myanmar and Cox’s Bazar.

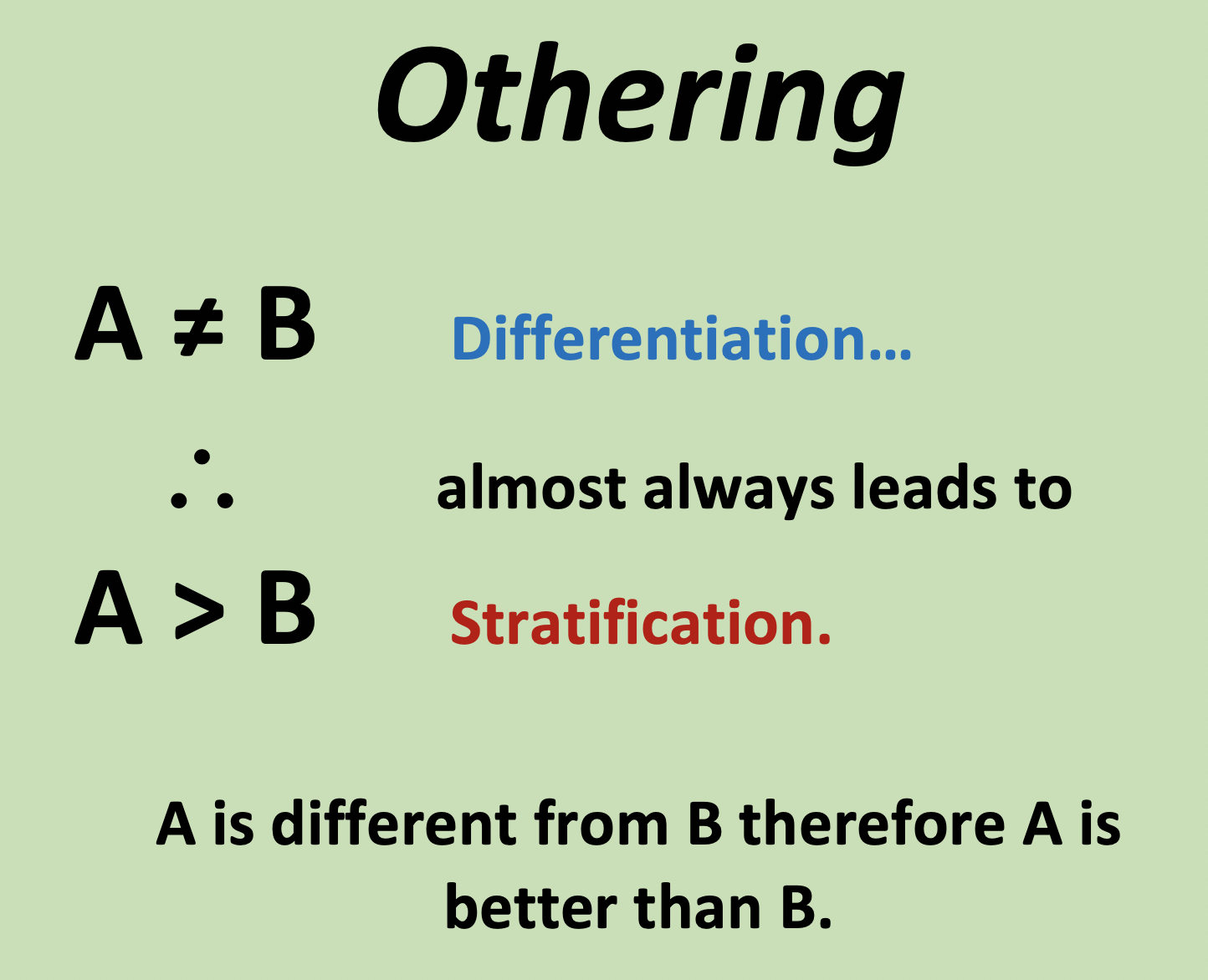

Othering 101

In the most basic of terms, othering can be stated as follows: If A and B are different, A will posit superiority over B, and if there is an asymmetry of power with A having more, A will impose it’s will on B.

A can be different from B is many ways, and the most critical variables include various social statuses, most ascribed, i.e., assigned at birth and/or otherwise not chosen. These include (but are not limited to), you guessed it, gender, sexuality, body type, race/ethnicity/tribe, religion, age, social class, ability, and colonial status.

Key to mention here is that othering can be something done by one person to another person or group and/or from one group to another. Indeed, unit of analysis matters as you get into the weeds describing and understanding othering.

Key to mention here is that othering can be something done by one person to another person or group and/or from one group to another. Indeed, unit of analysis matters as you get into the weeds describing and understanding othering.

This dynamic, going from “difference/differentiation” to “one is better than the other/stratification” is virtually inevitable when A is more powerful than B. To wit, gender differentiation has, in the vast majority of cultures, always degenerated into gender stratification, oft times toxically so.

Othering is an inclusive, umbrella-like term, and all forms of marginalization are merely variations on this process. When there is a power imbalance the object of othering (‘B’) tends to be dehumanized, counter- anthropomorphized, having its basic human qualities stripped, and seen as ‘less then.’

The ‘othering’ marginalization process impacts all aspects of the culture such that this dehumanization becomes normalized, baked into every aspect of the culture. When some forms of othering are institutionalized and even celebrated this can lead to an acceptance of othering in other realms. I am thinking here of the ‘national pride’ that is celebrated at the Olympics internationally and here in the US where, in my personal case, it is OK to talk trash about Michigan if you are an Ohio State fan like myself. Indeed, ethnic (‘othering’) jokes seem to be universal across cultures, and as Gershon Legman points out in his book No Laughing Matter, “Under the mask of humor our society allows infinite aggressions, by everyone and against everyone.”

Fast forward to the present and we can make the observation that patriarchy, colonialism/paternalism, heteronormativity, classism/racism are integral features of our global culture, all having their justification based on the simple thought that if A does not equal B then A is greater than B. And if A is stronger than B it can -and typically will- impose its will upon B.

Baked in = sociological a prioris

On a sociological note, that #alnap32 is taking place in Berlin is significant. Sociologist Georg Simmel spent his entire career in this city, and among his major concepts is the idea of sociological a prioris. Kant’s assumption was that humans are not born tabula rasa but rather come frontloaded with certain a priori structures that determine, for example, our concepts of space and time. For his part, Kant has been affirmed and his basic ideas extended by research into evolutionary psychology (as an example the cultural universal of craving sweet, salty, and/or fat foods).

Simmel endorses but also extends Kant by arguing that we live in a social world created by our ancestors, both ancient and even more recent. We live in a world of reified and ossified social structures which we internalize through the process of socialization; they become part of the way we understand, experience and, hence, act in the world. Othering in its many forms is part of the worlds in which we live and act. Sexism, racism, heteronormativity, just to name a few, have been literally baked into our social and cultural worlds. In some cases recognizing the more firmly entrenched othering structures demands a fundamental rethinking of our world, and hence our self. Confronting othering means finding ways to de-ossify existing mental and social structures. No small task, that.

Why othering persists: the better and not so better angels of our nature

While humans can imagine and even wax poetic about perfect justice, we are quite capable of acting otherwise. Though few would openly disagree when offered the observation that “we are all God’s children”, their actions speak otherwise. In US culture we see this clearly within the Evangelical movement which openly supports acts and policies of racism. In Myanmar, those who talk of following in the path of the Buddha end up perpetuating genocide. How does this duplicity happen?

In sociology we talk about ‘ideal culture’ and ‘real culture.’ Ideal culture reflects the better angels of our nature. It is seen in our formal documents and more progressive laws. In the US, the Constitution and Bill of Rights are such documents. Internationally, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents such lofty ideals.

The rhetoric of our ideal culture statements are driven, stated in psychological terms, by our superego, our conscience. These are the internalized and culturally accepted values which our religions, teachers, parents, and coaches have imparted on us and represent the positive, cohesive bonds that help maintain (relative) social order.

By contrast, our behavior, that is ‘real culture’, is driven by a more buried, primal part of our brain and is guided by fear, mistrust, and selfish motivations, the ‘motherboard’ mentioned above. Herein lies the core source of othering.

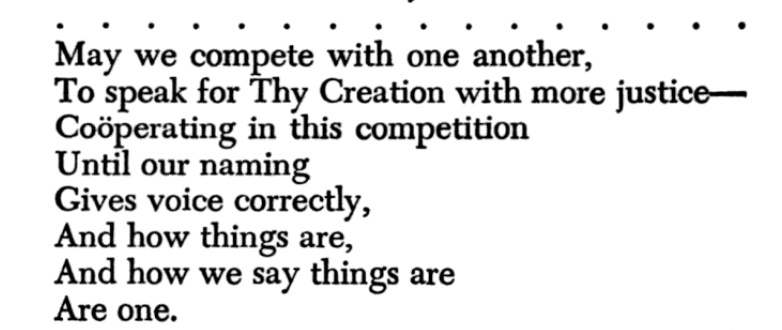

When Martin Luther King, Jr tells us, “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice” he is saying that our institutions collectively are slowly getting more progressive, and that some time in the future we will have a more just world. His assumption that the better angels of our nature -our ability to produce ‘ideal culture’ laws and structures- will eventually prevail, may be too optimistic. As we watch a world increasingly fueled by toxic nationalism and even outright fascism, the real culture of our othering tendencies seems to be winning this moral tug of war. Calling on Kenneth Burke’s poem “Dialectician’s Prayer”, we have to be sober to the fact that how things are, and how we say things are, are not one.

A note on ‘brown on brown’ othering

Though any rank ordering of the most toxic manifestations of othering would be difficult to defend, racism is certainly near the top of any list. Examples of racism -manifesting itself in many ways up to and including genocide- are depressingly easy to find as one scans the globe now and back through history. Many of these examples include intertribal (and even intra-tribal) conflicts and evidence of our tribe or group enslaving another. Racism can and has included white on white, white on people of color (POC), and POC on POC. The paradox -and the reality- is that a group can be at the same time the perpetrator of and the object of racism.

Taken up an analytical notch, one person or group being ‘othered’ and marginalized because of one ascribed status (for example race/ethnicity) does not preclude that same person or group marginalizing and othering based on another ascribed status (for example, sexual expression). And that gets used into the topic of the antidote to othering. In the current vernacular, the term being used is ‘woke.’

What does it mean for a humanitarian worker to be ‘woke’? For one perhaps painfully accurate answer (and some comic relief) look to the left.

Status, privilege, and being ‘woke’

From the humanitarian worker perspective, one very important factor determining comfort in the workplace is how accepted one feels concerning their various social statuses. There are many statuses, both ascribed and achieved (and some a hybrid) that, depending upon the social context, emerge as ‘master statuses’ which can significantly color how one is viewed, responded to, and ultimately either accepted or marginalized both socially and professionally. Among these statuses are gender, age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, level of education, and outstanding physical attributes. Adding to the complexity is the fact of intersectionality, the complex and inherent interconnection of power and marginalization that impacts everyone either directly or indirectly.

Most of us train ourselves to see beyond the surface (to become ‘woke’), but the reality is that life-long socialization into using specific cultural lenses sometimes can make us unaware of some of the assumptions we are making about ‘the other’. Recognizing, owning and then mindfully checking ones’ ethnocentrisms and various privileges is rarely a ‘one and done’ exercise, but rather a lifetime journey, especially for those -humanitarians, for example- who regularly encounter diversity in its many rich and complicated forms. Those with privilege must constantly be not only willing but ever ready to engage in anti-oppressive practices and encourage same in all our workmates.

On a reflexive -and sociological- note I’ll add that having certain ascribed statuses can make the journey toward ‘wokedome’ longer and harder (but all the more necessary!). As a cis, straight, ‘too male, too pale, and too stale’ person, I embrace and, critically, learn from that journey daily.

To be clear, privileges come in many forms, including (but not limited to) race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and nationality, and, yes, being from the ‘global North.’ Can privileges amplify each other if, as in my case, a person has multiple privileged statuses? Of course.

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality‘ many years ago to help us understand the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.

Perhaps we need a new word to describe the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple privileges combine, overlap, or intersect and thus amplify the power of these privileges in both individuals and groups. Having this word might help us in our never-ending journey toward personal and organizational relevance.

Circling back to relevance: fighting the Hydra

Two main points to conclude. First, understanding ‘othering’, as I point out above, is never a case of, ‘one and done.’ Borrowing from Sophia Swithern, we best think of it was an ‘iterative’ process. I’ll add that it is a process that needs to be done mindfully, systematically, and with a constant awareness of the hurdles that lie along that pathways of implementation. Closing the gap  between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’ takes constant work.

between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’ takes constant work.

Understanding othering (and acting in response to that understanding) is one dimension of being ‘woke’. Though the term ‘woke’ typically applies to an individual, all avatars of the humanitarian ecosystem -individuals at all levels, organizations (including ALNAP), and donor entities of various stripes) can also become more self-aware, more ‘woke.’ Those in positions of power must have the desire to become constantly more self-aware of their othering and to honing their ability to facilitate this journey among those with which they work. To repeat, this is an interactive process.

Secondly, in her background paper Sophia Swithern offers many on point questions which demand that the reader understand more clearly power, privilege and perspective, to look at the humanitarian sector with eyes wide open, looking for and recognizing ‘baked in’ personal, organizational, and sector-wide structures that marginalize those in the affected community (and perhaps each other). Her lessons shine light on the path forward and highlight the need to see more clearly the impacts of patriarchy, racism, colonialism, paternalism, hetero/cisnormativity, and classism.

The more that individual humanitarians, humanitarian organizations, and donor entities understand the process of othering and how to confront its manifestations the more relevant their actions will be. Swithern urges us to understand what the affected community really needs. I’ll suggest that people really need is to be free from marginalization, from being othered.

A Hydra, the many-headed serpent in Greek mythology, is a good analogy here for ‘othering’. This dragon-like beast is immortal, and when one of its heads is cut off two more grow in its place. So it is with othering, an ever-present demon humans must fight that has many toxic manifestations. As humanitarians this epic battle must be fought first in the service of relevance, of “… in line with the priority needs of affected people.” Finally, perhaps we should keep in mind that though fighting these demons individually is a natural impulse, perhaps the body should be attacked most vigorously.

Post script: Implementaion

Not long ago I had the chance to talk with Linda Polman, author of one of the more scathing books about the humanitarian sector, Crisis Caravan. We talked about relevance and about how the sector could improve. She said,

“Everybody inside the aid industry knows what should be done. Everybody knows how it could be better. But to implement all those recommendations, that’s the problem. To think of how it should be better, how it can be better, is not the difficult part, it’s the implementation part.”

True words, those. Talking about change (‘making our response more relevant’) is the easy part. The next step, going from discussion to writing or re-writing policy, procedures, or protocol is much more difficult. But words on documents only become action when implementation happens. The fact that the humanitarian sector is an open and highly complex system made up of thousands of bureaucratic entities, each with their own ossified structures, makes unilateral implementation a difficult and perhaps Sisyphean task. Coordination among and between all entities within the sector must continue and even intensify; we must all get on (and stay on) the same iterative ‘woke bus’.

And that’s why meetings like ALNAP are critically important, helping to facilitate and further inter and intra-sector forward progress on critical topics such as relevance. May we all be up to the task, whatever our parts may be.

Thanks for reading. As always, you can contact me here if you have feedback, questions, comments, or suggestions.

Follow

Follow