“We can never construct the best world in which our compassion can immediately translate into an end of suffering, but we can try to build a second-best world based on hard-headed assessments of the needs and options.”

–Fiona Terry, Condemned to Repeat: The Paradox of Humanitarian Action, p. 216

“It is presumed that market solutions are always to be preferred, that governments and regulators are generally incompetent, and that great wealth reflects superior intelligence or insight, rather than having anything to do with entrenched privilege or power.”

-page 6

Reactions to Vale the Humanitarian Principles: New principles for a new environment

Overview and thoughts

Australian academics Matthew Clarke and Brett Parris recently published Working Paper 001 for the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership at Deakin University. They take us up to 35,000 feet and offer nothing less than what they immodestly call “new principles” to guide humanitarian work.

Thoughtful critiques of the sector, like Fiona Terry’s Condemned to Repeat, are always important reads. See here for a very good 2004 essay by Beat Schweizer (“Moral dilemmas for humanitarianism in the era of “humanitarian” military interventions“) anticipating many of Clarke and Parris’s ideas. As I prepare to participate in ALNAP32 taking place soon in Berlin, Clarke and Parris’ observations provide useful grist for our ongoing conversations about ‘relevance’ in the humanitarian sector. Below are some of my thoughts as I read their essay.

The view from 248 miles up?

The humanitarian sector has come a long way in the last 20 years with increasing efforts at coordination and meaningful change in progressive directions. For example, there are now industry-wide standards (see CHS and Sphere) which inform and guide humanitarian responses. There can be hope that what Linda Polman describes in her 2010 book Crisis Carvan is, in fact, history that will not be repeated, certainly not now in 2019.

In reference to global humanitarian efforts, Clarke and Parris quote Hugo Slim saying, “At its best, it is a very practical affirmation of the value of human life and its unique character in each human person.” I agree with Slim that the humanitarian sector is in many ways the best of humanity. In other blog posts I have described the humanitarian sector as, collectively, the conscience of out collective consciousness.

However, my more critical response to Slim, on one level, is as flat no. While Clarke and Parris take us up to 35,000 feet, let’s examine what the situation looks like from the International Space Station, 248 miles above our Earth.

The roughly $30 million that was spent last year on all humanitarian aid is, in context, miniscule and indicates humanity’s lack of appropriate prioritization of human welfare. We spent as much on porn and Fortnight as we did on humanitarian aid last year. As measured by our spending patterns, humanity as a whole is quite frankly not very humane. Consumers in the US alone spent $9 billion dollars on Halloween this fall. In contrast, by unimaginable orders of magnitude more we are much more effective at waging war. That the humanitarian sector does not demand more attention to this disparity is an abrogation of responsibility, a kowtowing to the lament that ‘we’re doing the best that we can do, and it is someone else’s problem to look at the bigger picture.’ That we, humanity, can do better is a given. Who should lead that charge if not the humanitarian sector?

Expanding view in terms of timeframe

Having expanded our vision by looking from a higher vantage point, beyond critiquing the priority given the sector, the next logical step of expanding our temporal scope must be taken. Basic questions emerge immediately, ranging from our pre-human past to the not-too-distant future, these include,

- How was the humanitarian imperative responded to both by individuals and by organizations (religious or otherwise) before 1959, Dunant, and the Red Cross?

- In what ways was the humanitarian imperative articulated in non-Western cultures both pre and post Solferino?

- To what extent is the humanitarian imperative a cultural universal, a trait of most human cultures from the earliest of our species existence?

- Moving beyond an anthropocentric perspective, how far back phylogenetically can we trace a sense of empathy being shown from one being to another?

- How has the humanitarian ecosystem evolved in the last century, and that what geopolitical and economic forces, historical events, and what inter-and intra-cultural changes have impacted this evolution?

- And, perhaps most importantly, how and to what degree can/should the humanitarian sector prioritize planning for a future that will almost certainly include many more (and more extreme) ‘natural’ disasters and the wide array of human conflict crises to follow same, and as well also including non-climate related geopolitical conflicts?

These questions move us toward many big questions related to formulating humanitarian principles, and these include ones about our basic nature.

Lessons from the Nataruk massacre

‘Othering’ is basic to our species; there has always been an ‘us’ and ‘them’. There is evidence of violence between groups of hunting and gathering bands 10,000 years ago in Kenya that appear to have included “‘extreme blunt-force trauma to crania and cheekbones, broken hands, knees and ribs, arrow lesions to the neck, and stone projectile tips lodged in the skull and thorax of two men.’ Four of them, including a late-term pregnant woman, appear to have had their hands bound.”‘

Ethological evidence indicates that our closest relative, chimpanzees, are quite capable of attacking and killing rivals, providing support for the premise that inter-group enmity is woven into our basic nature. Our tendency to other is evidenced in every corner of the world all through human history.

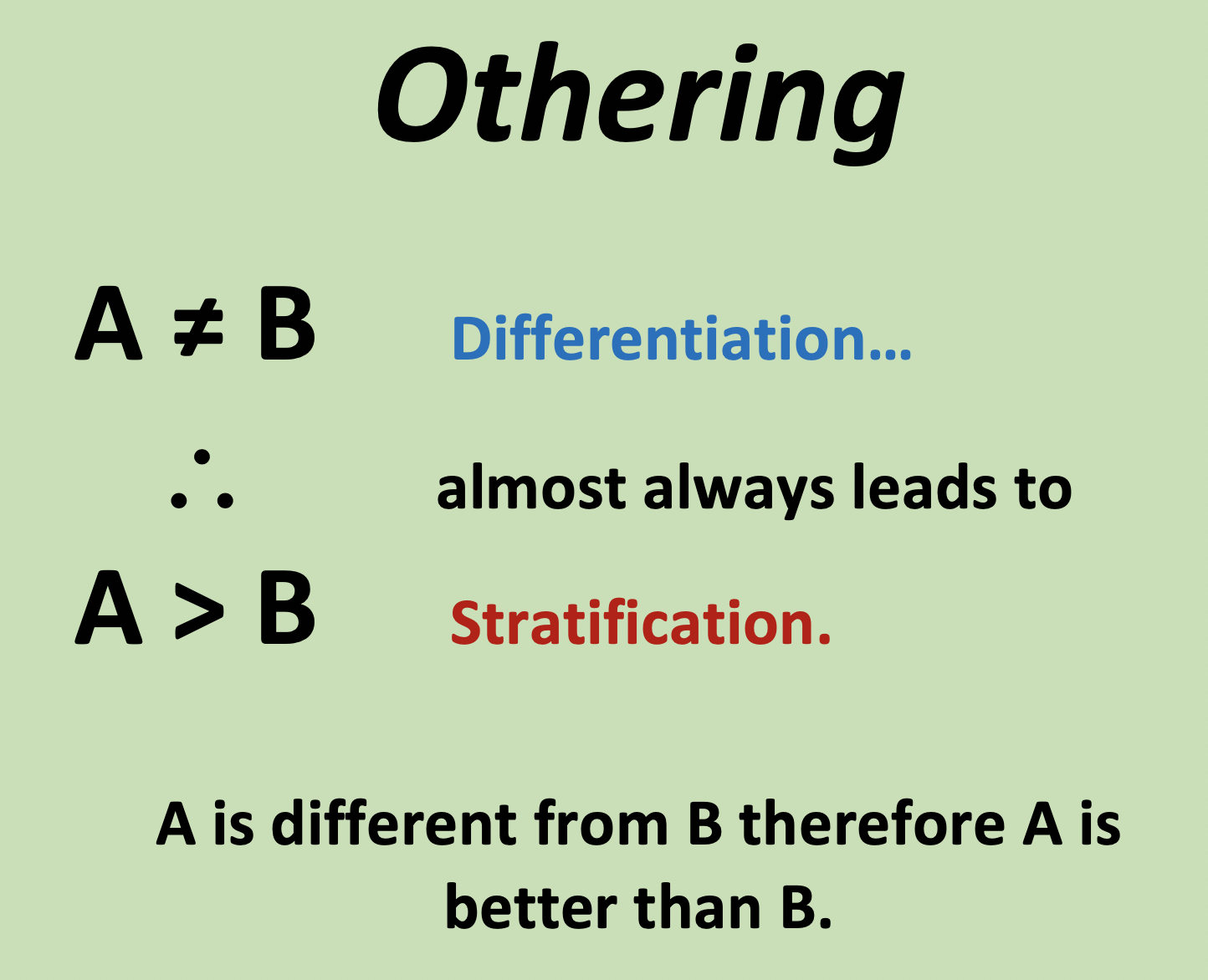

Othering

Though the exact origin, at least for some, is unclear, many scholars agree the earliest use of the term ‘othering’ comes from Edward Said’s classic 1978 book Orientalism. This term is inclusive of the entire range of marginalizing ‘isms’ and phobias including (but not limited to) ethnocentrism, racism, fascism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, and so on.

This quotation from an article comparing this book to George Orwells Burmese Days presents the concept and also anticipates some points I’ll cover below.

“Orientalism is closely related to the concept of the Self and the Other because as Said points out in his second definition of Orientalism, it makes a distinction between the Occident, i.e. self and the Orient, i.e. the Other, since the analysis of the relationship of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’ is at the heart of Postcolonialism and many define Postcolonialism in terms of the relationship of the self and the Other. For instance, Boehmer emphasizes that ‘Postcolonial theories swivel the conventional axis of interaction between the colonizer and colonized or the self and the Other’.”

Stated in the most basic of terms, othering can be stated as follows. From the perspective of A, if A is different from B it can be concluded that A is better than B. A can be different from B in many ways, and no matter what the variable, the dynamic is the same, with differentiation transitioning into stratification very easily, and especially so when this process has been modeled previously.

same, with differentiation transitioning into stratification very easily, and especially so when this process has been modeled previously.

The most critical variables include various social statuses, most ascribed, i.e., assigned at birth and/or otherwise not chosen. These include (but are not limited to), you guessed it, gender, sexuality, race/ethnicity/tribe, religion, age, social class, and colonial status.

Key to mention here is that othering can be something done by one person to another person or group and/or from one group to another; unit of analysis matters as you get into the weeds describing and understanding othering. This dynamic, going from “difference” to “one is better than the other” is virtually inevitable when A is more powerful than B. To wit, gender differentiation has, in the vast majority of cultures, always degenerated into gender stratification.

All forms of marginalization are merely variations on this process. When there is a power imbalance the object of othering tends to be counteranthropomorphized -taking away human qualities-, dehumanized, and seen as ‘less then.’ The ‘othering’ marginalization process impacts all aspects of the culture such that this dehumanization becomes normalized, baked into every aspect of the culture. Fast forward to the present and we can make the observation that patriarchy, colonialism/paternalism, heteronormativity, classism/racism are integral features of our global culture, all having their justification based on the simple thought that if A does not equal B then A is greater than B, and that is A is stronger than B it can -and typically will- impose its will upon B.

Why othering persists: the better and not so better angels of our nature

While humans can imagine perfect justice, we are quite capable of acting otherwise. Though few would openly disagree when offered the observation that “we are all God’s children”, their actions speak otherwise. In US culture we see this clearly within the Evangelical movement which openly supports racism. How does this duplicity happen?

In sociology we talk about ‘ideal culture’ and ‘real culture.’ Ideal culture reflects the better angels of our nature. It is seen in our formal documents and more progressive laws. In the US the Constitution and Bill of Rights are such documents. Internationally the Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents such lofty ideals.

The rhetoric of our ideal culture statements are driven, in Freudian terms, by our superego, our conscience. These are the internalized and culturally accepted values which our religions, teachers, parents, and coaches have imparted on us and represent the positive, cohesive bonds and maintain relative social order.

By contrast, our behavior, that is ‘real culture’, is driven by a more buried, primal part of our brain and is guided by fear, mistrust, and selfish motivations. Herein lies the core source of othering.

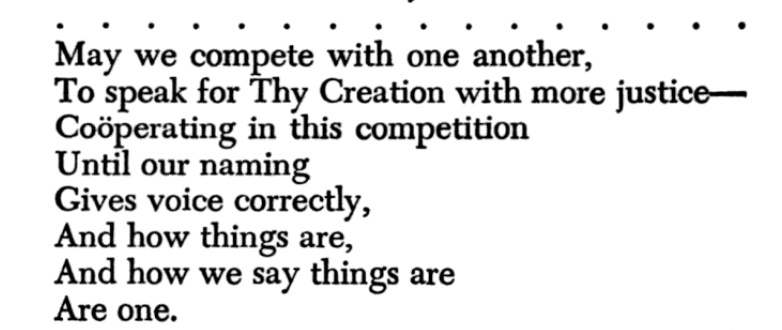

When Martin Luther King, Jr tells us, “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” he is saying that our institutions collectively are slowly getting more progressive, and that some time in the future we will have a more just world. His assumption that the better angels of our nature -our ability to produce ‘ideal culture’ laws and structures- will eventually prevail, may be too optimistic. As we watch a world increasingly fueled by toxic nationalism and even outright fascism, the real culture of our othering tendencies seems to be winning this moral tug of war. Calling on Kenneth Burke’s poem “Dialectician’s Prayer” we have to be sober to the fact that ‘how things are, and how we say things are, are not one.’

When some forms of othering are institutionalized and even celebrated this can lead to an acceptance of othering in other realms. I am thinking here of the ‘national pride’ that is celebrated at the Olympics internationally and here in the US where, in my personal case, it is OK to talk trash about Michigan if you are an Ohio State fan like myself.

Brown on brown on brown

Examples of othering -manifesting itself in many ways up to and including genocide- are depressingly easy to find as one scans the globe. Many of these examples include intertribal (and even intratribal) (add FB conversations)

Othering and being othered

Let’s take a list of ascribed statuses and rank order them in terms of the tendency to other or be orthered exists.

The higher the status, the less likely to be othered, the lower the status, the more likely. here we need to mention interscectionality

Additional points to make:

- the humanitarian ecosystem is not a monolithic whole and analytically should not be treated as such; my recommendation is that each region of the world be seen and treated as appropriate to the cultural context

- I will be laying out the main points of the Clarke and Parris article in more detail, with a special focus on how othering has been perpetuated by neoliberalism

- burning house example

- brown on brown on brown; racism in its various forms has always been with us

Insights from sociologist Georg Simmel

They posit that the humanitarian landscape is changing. The model presented by Henri Dunant in 1859

Old = humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence

New = equity, solidarity, compassion, diversity

Critiques of the ‘old’

Follow

Follow